Saving the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greta Thunberg Fact Sheet

Fact Sheet Greta Thunberg “I thought I couldn’t make a difference because I was so small.” Date of birth: 3rd January 2003 Nationality: Swedish Known for: Climate activism Greta Thunberg was a school child in Sweden who looked out at the world and saw things that she knew needed to change. Worried by changes to the world’s climate, Greta at first believed that she was too young to do anything. However, she could not stand by and do nothing. Less than a year after her first protest, Greta had become one of the most famous climate activists in the world, speaking to world leaders and helping to convince them that laws needed to change. Childhood Greta was born on January 3rd, 2003, in Sweden. Her mother was Malena Ernman, one of Sweden’s most celebrated opera singers. Her father was Svante Thunberg, an actor and author. Greta Thunberg | Page 1 copyright 2019 Fact Sheet One day at school, Greta’s teacher showed the class films about how mankind’s activities were changing the planet. She saw pictures of plastic polluting the oceans and learnt how polar bears were starving because climate change was drastically melting the ice where they lived. At the time, Greta’s classmates were concerned by this but their attention turned to other things after the lesson. Greta, however could not stop thinking about what she had seen. Greta soon became depressed about climate change. She started to worry that adults were not taking the issue seriously enough and wondered if she had a future. -

The Politics of Representation in the Climate Movement

The Politics of Representation in the Climate Movement Article by Alast Najafi July 17, 2020 For decades, the tireless work of activists around the world has advanced the climate agenda, raising public awareness and political ambition. Yet today, one Swedish activist’s fame is next to none. Alast Najafi examines how the “Greta effect” is symptomatic of structural racial bias which determines whose voices are heard loudest. Mainstreaming an intersectional approach in the climate movement and environmental policymaking is essential to challenge the exclusion of people of colour and its damaging consequences on communities across the globe. The story of Greta Thunberg is one of superlatives and surprises. In the first year after the schoolgirl with the signature blond braids emerged on the public radar, her fame rose to stratospheric heights. Known as the “Greta effect”, her steadfast activism has galvanised millions across the globe to take part in climate demonstrations demanding that governments do their part in stopping climate change. Since she started her school strike back in August 2018, Greta Thunberg has inspired numerous and extensive tributes. She has been called an idol and the icon the planet desperately needs. The Church of Sweden even went so far as to playfully name her the successor of Jesus Christ. These days, Greta Thunberg is being invited into the corridors of power, such as the United Nations and the World Economic Forum in Davos where global leaders and chief executives of international corporations listen to her important message. Toward the end of 2019, her media exposure culminated in a nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize and an extensively covered sail across the Atlantic with the aim of attending climate conferences in New York and Chile. -

Otto Mã¼hl Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8sj1mv6 Online items available Finding aid for the Otto Mühl papers, circa 1918-circa 1997 Isabella Zuralski Finding aid for the Otto Mühl 2011.M.38 1 papers, circa 1918-circa 1997 Descriptive Summary Title: Otto Mühl papers Date (inclusive): circa 1918-circa 1997 Number: 2011.M.38 Creator/Collector: Mühl, Otto Physical Description: 47.79 Linear Feet(108 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The archive of Otto Mühl, co-founder and one of the main participants of Viennese Actionism, and founder of the living experiment known as the Friedrichshof Commune, includes his complete diaries and a wealth of theoretical writings about Actionism, the concept of Action Analysis, and life in a commune as an alternative model of society. Also present is his correspondence; legal documents relating to court proceedings against Mühl and other participants of Viennese Actionism; approximately 1000 negatives and contact sheets of Mühl's actions taken by the Austrian photographer Ludwig Hoffenreich; circa 165 sketchbooks with drawings and writings by Mühl; and a collection of press reviews of Viennese Actionism published in Austrian and German newspapers in the 1960s and 1970s. Also included is correspondence of Otto Mühl's family, various family documents and records, hundreds of personal photographs, and Mühl's juvenile drawings and writings. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. -

News Quiz #3619 – February 4, 2021

Name: ___________________________ News Quiz #3619 – February 4, 2021 CHALLENGE QUESTION What international games are held every four years? QUIZ QUESTIONS 1. The survey asked people specifically 6. The protestors in India are ... about … A. restaurant owners A. climate change B. cab drivers B. natural disasters C. farmers C. recycling 7. Hank Aaron was known as baseball’s … 2. The survey was conducted by the … A. Batting King A. World Wildlife Fund B. Home Run King B. United Nations C. Strike Out King C. Global Partners 8. The student-run service was organized by 3. When a government official is charged with a school … a crime, they are … A. teacher A. guilty B. superintendent B. elected C. principal C. impeached 9. Locate Sweden on the map. 4. The only U.S. president to be charged twice is … A. Bill Clinton B. Donald Trump C. Richard Nixon 5. The agency with big space plans for 2021 is … A. ESA B. NASA C. CNSA 10. The New Orleans homes are being decorated for … A. Mardi Gras B. Valentine’s Day C. Easter OPINION QUESTION What person in history do you most admire? Why? News Quiz #3619 – February 4, 2021 Terms used in this week’s News Quiz: President Joe Biden Red Fort climate change emperor environment economy United Nations Development Programme Hank Aaron Peoples’ Climate Vote Milwaukee Brewers generation Atlanta Braves renewable energy Major League Baseball or MLB U.S. Senate Home Run King impeachment Georgia President Donald Trump Baseball Hall of Fame U.S. House of Representatives enshrine evidence Texas ‘incitement of insurrection’ Anthony Love U.S. -

René Cassin's Women's Seder

RENÉ CASSIN'S WOMEN'S SEDER René Cassin's Women's Seder celebrates the women of the exodus, their untold stories, and the individuals who inspire us today D e s i g n e d a n d p r o d u c e d b y R e n é C a s s i n w w w . r e n e c a s s i n . o r g ; M a r c h 2 0 2 0 W i t h t h a n k s t o t h e L i t t l e B u t t e r f l y F o u n d a t i o n , t h e P e a r s F o u n d a t i o n a n d t h e S i g r i d R a u s i n g T r u s t f o r m a k i n g t h i s r e s o u r c e p o s s i b l e F I N T R O D U C T I O N O S 3 J U S T I C E R U T H B A D E R G I N B U R G O N E 4 L P A S S O V E R T B R E N É C A S S I N ' S S E D E R P L A T E A 6 T N 7 R E S I S T A N C E : F I R S T C U P 8 F O U R Q U E S T I O N S E F O U R D A U G H T E R S 10 T 14 T H E T E N P L A G U E S 16 S O L I D A R I T Y : S E C O N D C U P N 17 E M P O W E R M E N T : T H I R D C U P 18 L E G A C Y : F O U R T H C U P O 20 F I N A L W O R D S C 21 M I R I A M ' S C U P 22 T H E S P E A K E R S 24 T H E O R G A N I S A T I O N S A D D I T I O N A L R E S O U R C E S 26 30 A B O U T R E N É C A S S I N "She was warned, She was given an explanation, Nevertheless, She Persisted" Senator Mitch McConnell, The Majority Leader about Senator Elizabeth Warren (2017) In February 2017 Senator Elizabeth Warren was reprimanded in a debate over Trump’s nomination to U.S. -

Greta Thunberg

AUTISTIC PRIDE MONTH APRIL GRETA THUNBERG Greta Thunberg (b. January 3, 2003), is a climate change activists who grew up in Stockholm, Sweden. She started campaigning for climate change in May 2018, at age 15, when she won a climate change essay competition in a local newspaper. She led a campaign outside Swedish Parliament to call for action on climate change by holding up a sign reading Skolstrejk för klimatet ("school strike for climate"). She went on to become a leading voice on the issue, inspiring millions to join protests around the world. Thunberg was named Time magazine's person of the Year in 2019. Thunberg has shown the world that nothing can interfere with the fulfillment of her mission of climate activism. Not cyberbullying. Not expressions of opposition, some from prominent players. And perhaps most remarkably, not an autism spectrum diagnosis. In fact, her autism profile is arguably an asset as she sets forth in winning over hearts and minds across the globe. Asperger's syndrome, which is Greta's autism spectrum diagnosis, is frequently accompanied by other disorders. In her case, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is relevant, which likely contributes to her intense and unrelenting focus on speaking truth to power in urging action on climate change. She has even described her Asperger's syndrome as a gift and said AUTISTIC SELF ADVOCACY NETWORK being different is a "superpower." Autistic self-advocacy became organized in the 1990s as a self-sufficiency ? the four goals of the Americans with part of the disability rights movement. The Autistic Self Disabilities Act ? they needed representation wherever issues Advocacy Network was founded in 2006 in response to the that impacted their lives were under discussion. -

Eco-Anxiety: a Discourse Analysis of Media Representations of the School Strike for Climate

Running head: YOUTH CLIMATE CHANGE MOVEMENT 1 Eco-Anxiety: A Discourse Analysis of Media Representations of the School Strike for Climate Movement Brittany Smith This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the Honours degree of Bachelor of Psychological Science (Honours) School of Psychology Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences The University of Adelaide Submission Date: 29 September 2020 Word count: 9,083 YOUTH CLIMATE CHANGE MOVEMENT 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .........................................................................................................................2, 3 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................4 Abstract ............................................................................................................................................5 Declaration .......................................................................................................................................6 Contribution Statement ....................................................................................................................7 Acknowledgements ..........................................................................................................................8 Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 1.1. Overview ...................................................................................................................9 -

El Caso De El Cabrito En La Gomera

Curso 2012/13 HUMANIDADES Y CIENCIAS SOCIALES/20 I.S.B.N.: 978-84-15939-19-1 RALPH JOSEF KISTLER La modernidad y los territorios del ocio: el caso de El Cabrito en La Gomera Director JOSÉ MARÍA DÍAZ CUYÁS SOPORTES AUDIOVISUALES E INFORMÁTICOS Serie Tesis Doctorales humanidades 20 (Ralph Josef Kistler).indd 1 26/02/2014 7:20:50 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 1.1. Agradecimientos ...................................................................................................................... 9 1.2. La comuna de El Cabrito en el contexto de las vanguardias artísticas de los sesenta ........ 11 y su relación con el imaginario turístico de las Islas Canarias 1.3. El caso de El Cabrito: metodología y estado de la cuestión ................................................. 32 ANTECEDENTES DE LA COMUNA DE OTTO MUEHL EN OTRAS COMUNAS UTÓPICAS DE LA MODERNIDAD 2.1. Charles Fourier y los inicios de las utopías sociales en la modernidad. ............................... 45 2.2. La comunidad Oneida de John Humphrey Noyes ................................................................ 49 2.3. La comunidad utópica del Monte Verità ................................................................................ 56 LA EVOLUCIÓN ARTÍSTICA DE OTTO MUEHL HASTA 1971 3.1. Juventud, desarrollo artístico y participación en el Accionismo Vienés ................................ 63 3.2. ZOCK – Aspectos de una revolución total ............................................................................ 78 HISTORIA E IDEOLOGÍA DE LA COMUNA (1970-87) 4.1. Índice de abreviaturas -

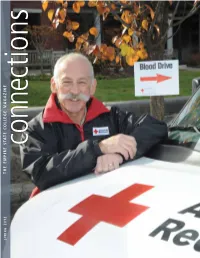

Spring 2012 Connections Magazine (PDF

Nonprofit Org. U.S. Postage PAID 2 Union Ave. Permit No. 19 Saratoga Springs, NY 12866-4390 Saratoga Springs, NY 12866-4391 printed on recycled paper MAGAZINE COLLEGE STATE connections connections EMPIRE THE Artwork by Ivy Stevens-Gupta, above, winner of the 2011 Student Art Contest, who explains in her artist’s statement that her experience with the college inspired her to start Ivy Stevens, Central New York Center painting again after many years away from her easel. 2012 Empire State College STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Field of Flowers • Student Art Award 2011 SPRING It’s time to start making your plans to come to Saratoga Springs for our signature summer events. Our annual day at Saratoga Race Course is Friday, July 27 and our annual evening at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center is Friday, August 17. For our out-of-town visitors, we will secure room blocks at our local hotels. We invite you to come and enjoy this charming and historic community and, of course, to spend time with good friends at SUNY Empire State College. We hope to see you and your families! Saratoga For more information or to sign up online, go to www.esc.edu/AlumniEvents. Summer There’s nothing like it. Make a decision today to create a better tomorrow Create a better tomorrow by including Empire State College in your will today. Your bequest can make college more affordable for a deserving student in need. With your investment, you give the gift of opportunity to our students working to improve their lives and their communities. -

Exploring the Perceptions of Diversity by Minority Journalists in the Wake of Shrinking Newsroom Staffs A

A Seat at the Table: Exploring the Perceptions of Diversity by Minority Journalists In the Wake of Shrinking Newsroom Staffs A thesis submitted to the College of Communication and Information of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By Mark A. Turner August, 2014 Thesis written by Mark Turner B.A., Louisiana Tech University, 1992 M.A., Kent State University, 2014 Approved by Danielle Sarver Coombs, Ph.D., Advisor Thor Wasbotten, M.S., Director, School of Journalism and Mass Communication AnnMarie LeBlanc, Dean, College of Communication and Information Table of Contents Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................ iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. LITERATURE REVIEW............................................................................................... 5 Theoretical framework............................................................................................ 9 Critical Race Theory................................................................................... 9 Framing Theory........................................................................................ 13 Cascading Activation Model....................................................... -

3. Tamera As a Healing Biotope 20 the History of Tamera 20 Space, Organizational Structure and Demography 22 Free Love and Sexuality in Practice 24

Free love and save the world An anthropological analysis of how a free love culture is defined, maintained and communicated in the polyamorous community, Tamera, Portugal Astrid Uldum Fabrin URL (6) Department of Social Anthropology SANK02 - VT2016 Supervisor Tova Höjdestrand Abstract This thesis investigates the social structures and discourse behind a culture of free love in a rural community in Portugal called Tamera. It describes how emotions and communication regarding personal romantic and sexual relationship are dealt with, as well as the incentives behind creating such a culture. Throughout the analysis I describe the political theory and vision behind the project Tamera and how these ideas are, or are not, manifested in reality. Based upon participatory observation and empirical examples I explain the history and development of the project; the space, organizational structure and demography of Tamera; and the tools and institutions applied to communicate around issues of love, sexuality and relations. I provide ethnographic descriptions of the social institutions: social transparency, the forum, studying and teaching, the texts of Dieter Duhm, and the language, followed by discussions of their use. Additionally, I include my personal reflections, criticism and feedback to Tamera. Findings show that the vision of free love is ideologically contextualized in the writings of Dieter Duhm based on the belief that there cannot be peace on Earth as long as there is war in love, and that there is war in love as long as we do not deal with our inner violent structures, Tamera underlines the importance of personal development. Through encouraging intimate physical contact, practicing social transparency and the forum, Tamera creates a culture in which polyamory thrives. -

Syndicated Columnist Assignment

SYNDICATED COLUMNIST ASSIGNMENT This portion of the summer reading assignment provides students with a measure of choice, and is intended to allow them to spread the work over the course of a few weeks, although this assignment may also be completed in less time by using archived material. Students are to select two columnists from the list below and read a minimum of five columns by the same columnist, writing a rhetorical précis (pronounced “pray-see”) for each column using the guide provided. A brief biography of each columnist is provided (most are quoted or paraphrased from the corresponding newspaper site); students may wish to read one sample column from several writers listed below before settling on the two columnists who will be central to completing this assignment. A diverse selection of columnists has been provided; additional suggestions are welcomed. List of Syndicated Columnists Charles Blow Visual Op-Ed columnist who won first John Gould An American humorist, essayist, and New York Times two best in show awards from the Christian columnist who wrote a column for the Saturday Malofiej International Infographics Science Monitor Christian Science Monitor for over sixty Summit for work that included deceased; check years from a farm in Lisbon Falls, coverage of the Iraq war. archives Maine. He is known for his role as a mentor to novelist Stephen King. David Brooks He has been a senior editor at The Bob Herbert Prior to joining The New York Times, New York Times Weekly Standard, a contributing editor New York Times Mr. Herbert was a national Tuesday & Friday at Newsweek and the Atlantic Tuesday & correspondent for NBC from 1991 to Monthly, and he is currently a Saturday 1993, reporting regularly on “The commentator on “The Newshour with Today Show” and “NBC Nightly Jim Lehrer.” He is also a frequent News.” He had worked as a reporter analyst on NPR’s “All Things and editor at The Daily News from 1976 Considered” and the “Diane Rehm until 1985, when he became a columnist Show.” His articles have appeared in and member of its editorial board.