Extended Gender & Diversity Roadmap 2018–2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IMES Alumni Newsletter No.8

IMES ALUMNI NEWSLETTER Souk at Fez, Morocco Issue 8, Winter 2016 8, Winter Issue © Andrew Meehan From the Head of IMES Dr Andrew Marsham Welcome to the Winter 2016 IMES Alumni Newsletter, in which we congrat- ulate the postgraduate Masters and PhD graduates who qualified this year. There is more from graduation day on pages 3-5. We wish all our graduates the very best for the future. We bid farewell to Dr Richard Todd, who has taught at IMES since 2006. Richard was a key colleague in the MA Arabic degree, and has contributed to countless other aspects of IMES life. We wish him the very best for his new post at the University of Birmingham. Memories of Richard at IMES can be found on page 17. Elsewhere, there are the regular features about IMES events, as well as articles on NGO work in Beirut, on the SkatePal charity, poems to Syria, on recent workshops on masculinities and on Arab Jews, and memories of Arabic at Edinburgh in the late 1960s and early 1970s from Professor Miriam Cooke (MA Arabic 1971). Very many thanks to Katy Gregory, Assistant Editor, and thanks to all our contributors. As ever, we all look forward to hearing news from former students and colleagues—please do get in touch at [email protected] 1 CONTENTS Atlas Mountains near Marrakesh © Andrew Meehan Issue no. 8 Snapshots 3 IMES Graduates November 2016 6 Staff News Editor 7 Obituary: Abdallah Salih Al-‘Uthaymin Dr Andrew Marsham Features 8 Student Experience: NGO Work in Beirut Assistant Editor and Designer 9 Memories of Arabic at Edinburgh 10 Poems to Syria Katy Gregory Seminars, Conferences and Events 11 IMES Autumn Seminar Review 2016 With thanks to all our contributors 12 IMES Spring Seminar Series 2017 13 Constructing Masculinities in the Middle East The IMES Alumni Newsletter welcomes Symposium 2016 submissions, including news, comments, 14 Arab Jews: Definitions, Histories, Concepts updates and articles. -

TLS Beoordelingsrapport Onderzoek Tilburg Law School 2016.Pdf

Assessment Report Tilburg Law School Peer Review 2009 – 2015 March 2017 1 Table of contents Preface ..................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ....................................................................................... 4 1.1 The evaluation ............................................................................. 4 1.2 The assessment procedure ............................................................ 4 1.3 Results of the assessment ............................................................. 5 1.4 Quality of the information ............................................................. 5 2 Structure, organisation and mission of Tilburg Law School ........................ 7 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................ 7 2.2 Management and organization ....................................................... 7 2.3 Mission and strategy of Tilburg Law School ...................................... 8 3 Assessment of Tilburg Law School research .......................................... 10 3.1 Assessment:.............................................................................. 10 3.2 Research quality ........................................................................ 10 3.3 Relevance to society ................................................................... 11 3.4 Viability .................................................................................... 11 3.5 TLS research programmes.......................................................... -

Research Review Tilburg School of Economics and Management

Research Review Tilburg School of Economics and Management Quality Assurance Netherlands Universities (QANU) Catharijnesingel 56 PO Box 8035 3503 RA Utrecht The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0) 30 230 3100 Telefax: +31 (0) 30 230 3129 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.qanu.nl Project number: Q 0487 © 2014 QANU Text and numerical material from this publication may be reproduced in print, by photocopying or by any other means with the permission of QANU if the source is mentioned. 2 QANU / Research Review Tilburg School of Economics and Management Report on the research assessment of the Tilburg School of Economics and Management at Tilburg University Contents Research Review Tilburg School of Economics and Management.............................. 1 Preface .............................................................................................................................5 1. The review committee and the review procedures......................................................7 2A. Research review of Tilburg School of Economics and Management......................9 2B. Program level .......................................................................................................... 17 2.B.1. Program: Accounting..................................................................................................19 2.B.2. Program: Econometrics..............................................................................................21 2.B.3. Program: Economics ..................................................................................................23 -

1 Faculty Exchange Programme Information 2020-2021

Faculty Exchange Programme information 2020-2021 Faculty Study Abroad Magali Dirven, (Elianne Berkepies) Coordinator(s) Address/building Steenschuur 25, 2311 ES, Leiden Phone number 0031715277609 Email [email protected] Walk-in-hours Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday from 11.00 – 12.00 hrs, Room C0.05 Website https://www.student.universiteitleiden.nl/studie-en- studeren/studeren-in-het-buitenland Blackboard Enroll yourself Blackboard page “studeren in het buitenland (BIO)” zie course ID “buitenland-permLAW” Best period to go on First or second semester (depending on your own personal exchange schedule you choose the semester you want to go on exchange) Application deadlines 1 Feb (for the whole academic year 2020-2021) (Erasmus+ and faculty wide agreements) Requirements You have to be a third year Bachelor student or Master student; You need to have at least 120 ECTS at the moment of selection (including your first-year diploma), preferably you have passed Contract Law, Constitutional and Administrative Law, Criminal Law and Property Law); You need to have a good motivation to study abroad; You have to be registered at Leiden University during your study abroad period. You pay your tuition fee to Leiden University which exempts you from paying a tuition fee to the partner university; You have to proof that you have a sufficient language proficiency of the language of instruction at the partner university. A minimum level of B2 is required for all universities (B2 = 7.0 average for final exam English VWO.) You can also do a language test at ATC Leiden). Some universities have extra (language) requirements, you can find those on the final pages. -

Breda - Tilburg - ‘S-Hertogenbosch Varen Langs Brabantse Steden

BREDA - TILBURG - ‘S-HERTOGENBOSCH VAREN LANGS BRABANTSE STEDEN 10 ANWB.NL/WATER 11 • 2016 TEKST EN FOTO’S: FRANK KOORNEEF EEN VAARTOCHT OVER DE BRABANTSE KANALEN KRIJGT AL GAUW HET KARAKTER VAN EEN STEDENTRIP. GEEN WONDER ALS JE BEDENKT DAT BREDA, TILBURG EN ’S-HERTOGENBOSCH DIRECT AAN HET WATER LIGGEN. CHARME V oor de meeste mensen zullen de aan- trekkelijke steden van Noord-Bra- bant de voornaamste reden zijn om een vaartocht over de Brabantse kanalen te maken. En dat is niet voor niets. Breda kop - pelt een oergezellige, oude binnenstad aan een rijk verleden vol belegeringen, waarin stadskastelen zoals het Spanjaardsgat een belangrijke rol in speelden. Wat Tilburg aan stedenschoon tekort komt, maakt de stad weer goed door zijn bedrijvigheid en gezelligheid. Ook heeft de stad een paar zeer interessante musea. Toppunt van Brabantse charme is wellicht ’s-Hertogenbosch, waar het Bourgondische Brabantse leven bijna spreekwoordelijk is. Tussen de steden ligt meestal maar een paar uur varen, alleen de afstand Tilburg-’s-Hertogenbosch is over het water wat langer. Maar dankzij diverse aanlegplaatsen onderweg is dit traject ook prima in twee dagen te doen. Niet alleen steden Omdat het zo voor de hand ligt om in Bra- bant van stad naar stad te varen, zou je haast vergeten dat tussen deze steden het Tip 1 Brabantse platteland ligt. Op veel plekken, Maak een rondje over de met name aan het Wilhelminakanaal, vaar stadssingels van Breda. Dat je door een bijzonder vriendelijk en bosrijk landschap, waar je prima kunt wandelen kan vanwege de vele vaste of fietsen. Safari- en attractiepark Beekse bruggen alleen met de bijboot Bergen vormt een bijzondere tussenstop of een (huur-)sloepje en beschikt over een eigen beschut gelegen jachthaven. -

Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences

Display copy - Inkijkexemplaar Partner universities of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology Copenhagen University (Denmark) University of Tromso (Norway) University College London (UK) Université René Descartes, Parijs (France) Freie Universität, Berlin (Germany) Ludwig-Maximilians Universität, München (Germany) Ruprecht-Karls Universität, Heidelberg (Germany) Education and Child Studies Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (Belgium) Roskilde University (Denmark) Aarhus Universitet (via University college) (Denmark) Universität Trier (Germany) Universität Kassel (Germany) Karl Franzens Universität (Austria) Koç University (Turkey) Yasar University (Turkey) Şehir University (Turkey) Political Science University of Antwerp (Belgium) Universite Libre de Bruxelles (Belgium) Ruprecht-Karls-Universität (Germany) Universität Konstanz (Germany) Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Grenoble (France) National University of Ireland (Ireland) Universita di Bologna (Italy) Universitet I Bergen (Norway) University of Oslo (Norway) Charles University (Czech Republic) Bilkent University (Turkey) Bogazici University (Turkey) Aberystwyth University (UK) Raadpleeg BB-pagina Study Abroad Political Science voor het actuele aanbod. Partner universities mentioned on this list are subject to change. No rights may be derived from the information above. Display copy - Inkijkexemplaar Psychology Universität Wien (Vienna, Austria) Universiteit Gent (Gent, Belgium) KU Leuven (Leuven, Belgium) Charles University (Prague, -

Political Science in the Netherlands

POLITICAL SCIENCE IN THE NETHERLANDS REFLECTIONS ON THE STATE OF THE ART QANU Catharijnesingel 56 PO Box 8035 3503 RA Utrecht The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0) 30 230 3100 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.qanu.nl Project number: Q0613.SOTA © 2018 QANU Text and numerical material from this publication may be reproduced in print, by photocopying or by any other means with the permission of QANU if the source is mentioned. 2 State of the Art Political Science CONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 The NVAO Assessment Political Science ........................................................................... 7 Composition of the NVAO Assessment Panel ........................................................................ 7 Working Method of the Assessment Panel for the State of the Art Report ................................. 7 Terms of Reference for the State of the Art Report ............................................................... 8 Political Science Education in the Netherlands: Reflections on the State of the Art ........ 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 11 Purposeful Curriculum Design and Development .................................................................. 11 Debates About Higher Education ........................................................................................ 12 Starting with Outcomes ................................................................................................... -

Voorlopig Voorkeursalternatief 150 Kv-Net Tilburg Noord – Best – Eindhoven Noord

Werken aan hoogspanning Voorlopig Voorkeursalternatief 150 kV-net Tilburg Noord – Best – Eindhoven Noord Tilburg Noord – Best – Endhoven Noord Werken aan netversterking COBRAcable (Denemarken) en netuitbreiding NorNed (Noorwegen) Voorlopig Voorkeursalternatief Eemshaven 150 kV-net Tilburg Noord – Best – Meeden Eindhoven Noord Ens Hollandse Kust (noord) Alpha Zwolle Beverwijk Aanpassingen 150 kV-net Tilburg Noord – Hengelo Hollandse Kust (zuid) Alpha Diemen Hollandse Kust (zuid) Beta Arnhem Best – Eindhoven Noord Bleiswijk Westerlee Dodewaard Omdat in de regio Brabant steeds meer elektriciteit BritNed (Groot-Brittannië) Maasvlakte wordt verbruikt en duurzaam wordt opgewekt, Geertruidenberg neemt ook het transport van elektriciteit toe. Borssele Beta Borssele Alpha De huidige bovengrondse 150 kV-verbinding Borssele (2 circuits) tussen Tilburg Noord en Best heeft Maasbracht binnen enkele jaren te weinig transportcapaciteit om aan de groeiende vraag naar elektriciteit te kunnen voldoen. Ook is deze verbinding verouderd TenneT is als landelijke netbeheerder van en is er groot onderhoud aan de masten nodig. het hoogspanningsnet verantwoordelijk voor TenneT wil deze verbinding vervangen door een de leveringszekerheid van elektriciteit. nieuwe ondergrondse kabelverbinding, mits dit Om die nu en in de toekomst te kunnen technisch, planologisch en financieel mogelijk is. garanderen, werken wij aan diverse Het project bestaat uit een aantal verschillende onderdelen: aanpassingen en uitbreidingen van het • In bestemmingsplan vastleggen ondergrondse elektriciteitsnet. Zo zorgen wij ervoor dat 150 kV-verbinding tussen Tilburg Noord en Best iedereen in Nederland 24 uur per dag, (2 circuits) en tussen Tilburg Noord en Eindhoven Noord (1 circuit). 7 dagen in de week beschikt over • In bestemmingsplan vastleggen koppelpunt en elektriciteit. In Brabant wordt gewerkt aan hoogspanningsstation Oirschot (ter vervanging het versterken en uitbreiden van het hoog- van huidig koppelpunt Oirschot Gijzelaar en aan- spanningsnet. -

Social Sciences the Art of Understanding the Human Society and Psyche Is Not Limited to Understanding Those Who Live in the United States

STUDY ABROAD WITH: @BrannenburgGate social sciences The art of understanding the human society and psyche is not limited to understanding those who live in the United States. In order to properly and fully grasp the entirety of the social sciences, you have to have a broader point of view. This year, take your sociology and psychology courses in a foreign country and gain a new perspective on our global culture. Academic Programs Abroad is here to help you spend a semester or a year at these universities oering classes in the social scienes and more. With all these exciting options, why not geaux? featured programs: UNIVERSITY OF EAST ANGLIA* Norwich, England - Ranked in Top 15 Psychology departments - 3rd in Quality of Teaching - 1st in Learning Resources - Hosts the Centre for Research on Children and Families, used by UNICEF Childwatch International Research Network LINNAEUS UNIVERSITY* Växjö, Sweden - Prominent in the eld of research in ready to get started? the social sciences 103 Hatcher Hall - Most are in English but some classes oered in [email protected] German, Swedish, French, lsu.edu/studyabroad and Spanish @geauxabroad @LSU Study Abroad where will you geaux? STUDY IN ENGLISH STUDY IN GERMAN STUDY IN SPANISH AUSTRIA AUSTRALIA KOREA ARGENTINA Johannes Kepler Universitaet Linz Charles Sturt University Ajou University Universidad Catolica de Cordoba Karl-Franzens- Universitaet Graz La Trobe University* Ewha Womans University Universidad de Palermo Universität Salzburg Macquarie University Keimyung University Universidad del -

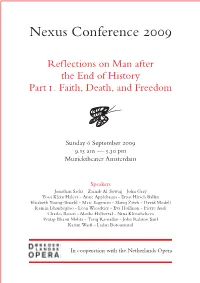

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

Tilburg University in the Netherlands

Tilburg University in The Netherlands At Tilburg University, there are about 13,000 students including international students from almost 30 countries around the world. More than 10% of the population of Tilburg is students, making the city a vibrant place to study. During the 2018-2019 academic year, one U of M Law student participated in the semester exchange. Summary of Course Offerings https://www.tilburguniversity.edu/education/exchange-programs/courses/ Semester Dates 2019-20 (including Intro week) Fall semester: Mid-August through end of November; exams in December and January Spring Semester: Late January through mid-June; exams in late June and July Language of instruction English Courses/Credits/Grades Up to 15 credits may be transferred per semester abroad Each class period is 90 minutes, not including a 15 minute break 2 ECTS Credits = 1 Minnesota Credit The minimum course load for exchange students is 24 ECTS credits per semester (typically four courses) Registration Information is sent to students after nomination regarding online registration. Participate in our Law School’s lottery for the term you will be away. Register for 12-15 credits. Before leaving for your semester abroad, contact the Law School registrar at [email protected] to convert your credits to Off-campus Legal Studies. Housing Tilburg University has an agreement with www.yourroomintilburg.com that offers international students furnished rooms. Financial Aid and Tuition Payment Financial aid will remain in effect for the semester you are abroad. Please make arrangements to have the balance (after tuition is deducted) sent to you if disbursement occurs after you have departed the U.S. -

Welcome to Tilburg University

WELCOME TO TILBURG UNIVERSITY STUDY ABROAD & EXCHANGE FACT SHEET 2020/21 CONTACT STUDY ABROAD & EXCHANGE TEAM MS. ANNA RATHERT TEAM LEADER MR. LARS MENNEN STUDY ABROAD & EXCHANGE COORDINATOR (IN- & OUTBOUND EXCHANGE) Region: Canada, Ireland, UK & USA MS. ELS BLAAUW STUDY ABROAD & EXCHANGE COORDINATOR (IN- & OUTBOUND EXCHANGE) Region: Latin America & Latin Europe (France, Italy, Malta, Portugal & Spain) MS. RACHAEL VICKERMAN STUDY ABROAD & EXCHANGE COORDINATOR (IN- & OUTBOUND EXCHANGE) Region: Asia (excluding South East Asia) & the Middle East MS. MARA CORNELIS STUDY ABROAD & EXCHANGE COORDINATOR (IN- & OUTBOUND EXCHANGE) Region: South East Asia & Oceania MS. MILOU KAUFFMAN STUDY ABROAD & EXCHANGE COORDINATOR (IN- & OUTBOUND EXCHANGE) Region: Europe (excluding Latin Europe) & Africa MS. HELEEN ZUIDEMA & MR. BRAM VAN DE SANDE STUDY ABROAD & EXCHANGE OFFICERS (IN- & OUTBOUND EXCHANGE) VISITING ADDRESS POSTAL ADDRESS Tilburg University – International Office Tilburg University Intermezzo Building – Room I 612 PO Box 90153 Professor de Moorplein 521 5000 LE Tilburg 5037 DR Tilburg The Netherlands The Netherlands ERASMUS INSTITUTION CODE WEBSITE tilburguniversity.edu/exchange NL TILBURG 01 facebook.com/TilburgUAbroad instagram.com/tilburguabroad twitter.com/TilburgU_Eng youtube.com/TilburgUniversity Updated by Tilburg University International Office, June 2020. Subject to change. [email protected] 2 of 9 OUR CAMPUS GREEN SPACE & AN INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY ABOUT TILBURG UNIVERSITY Tilburg University is a thriving university specializing in Social Sciences and Arts & Humanities. Social connection, academic excellence, and a strong campus feeling are at the heart of our education experience. Understanding and serving society is what drives us. Our green campus offers an attractive base for fostering an international community where students and teachers can inspire and challenge each other.