C:\AAAA\ITP\CACTUS\WP FILES\CS Pegasus Bay FINAL.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tidal Hydrology in Pegasus Bay G

EARTH SCIENCE JOURNAL, VOL. 1, No. 2, 1967 TIDAL HYDROLOGY IN PEGASUS BAY G. J. BLAKE, Ministry of Works, Wellington Abstract Changes in the geomorphology of the coastal plain river mouths of Pegasus Bay over the last 100 years are considered. Comment is also made on estuarine sediment and flow, the difficulty of measuring these two quantities and the need to treat the estuarine channel of a river as an important part of the catchment. INTRODUCTION New Zealand hydrologists are very much concerned with river catchment analysis but as yet have not considered the tidal section in detail. The river channel from its mouth to the maximum distance upstream of tidal influence is a complex section where fluvial and marine processes combine and conventional flow gauging methods prove unreliable. Observations from the lower reaches of some typical New Zealand rivers (Blake, 1963) indicate some of the tidal channel details and gauging problems. The rivers studied in North Canterbury were:- Slope of Upstream River Catchment channel Saline Foreshore Area "Flow (100-0 ft. limit Sediment (Sq. Miles) m.s.l.) approx. at mouth (ft/ft) (mls) Waimakariri I 1250 Perennial 0.On18 2.00 Sand Ashley 447 Perennial 0.0034 0.75 Sand 95 Inter- 0.10054 0.25 Shingle Kowhai I mittent ·Waipara 285 Perennial 0:0054 0.25 Shingle CHANNEL FORM Wave action, generally reduced but variable flow velocities, aggradation and the tendency to meander combine to cause the mouth to migrate along the coastline. In several hundred years the Waimakariri river has moved along fifty miles of coastline north and south of Banks Peninsula (Jobberns, 1927). -

Electronic Files of Shear-Wave Velocity

USGS Award Number G16AP00003 REDUCING UNCERTAINTY OF LIQUEFACTION HAZARD ASSESSMENTS IN AGED SOIL DEPOSITS Final Report to the United States Geological Survey By: Barnabas Bwambale and Ronald D. Andrus Glenn Department of Civil Engineering Clemson University Lowry Hall, Box 340911 Clemson, South Carolina 29634-0911 USA Telephone: (864) 656-0488 Fax: (864) 656-2670 E-mail: [email protected] February 18, 2017 Research supported by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), Department of the Interior, under USGS award number G16AP00003. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Geological Survey. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. ii USGS Award Number G16AP00003 REDUCING UNCERTAINTY OF LIQUEFACTION HAZARD ASSESSMENTS IN AGED SOIL DEPOSITS Final Report to the United States Geological Survey by Barnabas Bwambale and Ronald D. Andrus Glenn Department of Civil Engineering Clemson University Lowry Hall, Box 340911 Clemson, South Carolina 29634-0911 USA Telephone: (864) 656-0488 Fax: (864) 656-2670 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The influence of aging processes (or simply age) on liquefaction resistance of Holocene and Pleistocene soils near Christchurch, New Zealand is evaluated in this report. Many Holocene alluvial and marine deposits in and around Christchurch experienced minor to severe liquefaction during the 2010-2011 Canterbury earthquake sequence. Liquefaction and permanent ground deformations were most severe in the city during the 22 February 2011 event. Permanent horizontal ground displacements up to 0.35 m also occurred at several locations in moderately sloping Pleistocene loess-colluvium in the Port Hills area, but no sand/silt boil has been connected to those deposits. -

Lot 193 - Ravenswood,Woodend

House & Land Package | Lot 193 - Ravenswood,Woodend Home: 131m2 Section: 450m2 1 3 2 1 FEATURES: Become part of a brand new exciting community in North Canterbury, Ravenswood is just 25kms north of Christchurch City and five minutes from the beach in Pegasus Bay, the Waimakariri District is one of New Zealand?s fastest growing districts with a population of over 50,000 people. This design features three double bedrooms, main bathroom, ensuite and WIR for the master bedroom, open plan kitchen/dining and living and a study nook. Titles out July 2018. North Canterbury towns have a sense of community that can be hard to find these days, with a pace of life that is just a little more relaxed. Ravenswood is close to many excellent educational centres from pre-schools right through to high school, it also has access to an array of extracurricular clubs and activities. Features: ? Family size section ? Brick cladding. ? Metal tile roofing. ? Open plan kitchen/living/dining. ? Separate bathroom ? Separate toilet. ? Heatpump. ? Mastercraft kitchen. ? F&P Appliances. Including Asphalt Driveway, Concrete Patio and Boundary Fencing. You still have time to choose your colours, fixtures, fittings, carpets and tiles. Check out the video below to see what it's like to build a home with the Signature Canterbury team. Our Guarantees: // Signature Homes Home Completion Guarantee // // Signature Homes 10 Year Weather Tightness Guarantee // // Signature Homes 10 Year Structural Guarantee // // Signature Homes No Hidden Extras Guarantee // // Signature Homes Fixed Price Contract Guarantee // // Signature Homes 2 Year Maintenance Guarantee // // Signature Homes Completion Date Guarantee // // Signature Homes Satisfaction Guarantee // Please get in touch with Signature Homes for guarantee terms andPrice: conditions. -

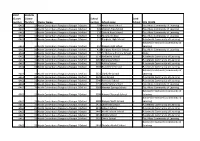

Pegasus & Woodend COMMUNITY DIRECTORY 2015

Pegasus & Woodend COMMUNITY DIRECTORY 2015 Local services, businesses, retail & community groups. Compiled and produced by the Pegasus Residents’ Group Inc. Post or drop off: 60 Infinity Drive, Pegasus 7612 Email: [email protected] www.pegasusresidentsgroup.com Photos courtesy of Todd Property Pegasus Town Ltd and Allan McGregor Photography Want to see rows and rows of “worn-out” Japanese “sewing-machines”? DON’T VISIT LIMITED 65 MAIN ROAD, WOODEND Always an interesting selection of quality used vehicles from $3,000 to $30,000 Call FRANZ anytime on 0800 92 34 34 Looking a er North Canterbury motorists for over 40 years! Page 2 Pegasus Community Directory 2nd Edition September 2015 INDEX ESSENTIAL SERVICES ...............................5 Real Estate .................................................11 LOCAL SERVICES, BUSINESSES, RETAIL Retail Dairy ................................................11 Accommodation ..........................................6 Retail Fruit And Vegetables .......................11 Auto ATV Sales and Service .........................6 Retail General Store ...................................12 Auto Motorcycle Repair...............................6 Retail Giftware ...........................................12 Auto Upholstery ..........................................6 Schools and Education ...............................12 Auto Used Car Sales ....................................6 Security ......................................................12 Celebrant .....................................................6 -

Pegasus, Woodend & Waikuku

Pegasus, Woodend & Waikuku COMMUNITY DIRECTORY 2019/20 Local services, businesses, retail & community groups Compiled and produced by the Pegasus Residents’ Group Inc. Available online at www.pegasusresidentsgroup.com Middle two photos courtesy of Allan McGregor Photography A-Z INDEX SEE PAGE 64 A familiar face to CATEGORY INDEX North Canterbury motorists ESSENTIAL SERVICES ............................. 4 Lions ............................................................. 13 Member of Parliament ................................. 14 COMMUNITY SUPPORT ........................ 5 Pet Home Care & Boarding ........................... 14 for over 40 years! Preschooler Activities/Playgroups ................ 14 LOCAL SERVICES, BUSINESS, RETAIL Photography/Video ...................................... 14 Accommodation ............................................. 6 Professional Services .................................... 14 Accounting/Bookwork .................................... 6 Promotional Services .................................... 15 Animal Care and Supplies ............................... 6 Real Estate .................................................... 15 Automotive Services ....................................... 6 Retail - Alcohol.............................................. 15 Car Sales ......................................................... 7 Retail - Antiques ........................................... 15 Celebrant ........................................................ 7 Retail - Arts & Crafts .................................... -

Kaiapoi Street Map

Kaiapoi Street Map www.northcanterbury.co.nz www.visitwaimakariri.co.nz 19 D To Woodend, Sponsored by Kaikoura and Picton SUTHERLAND DR WEARING BAYLISSPL DR Phone: 03 327 5379 MCKEE LN BLAIR Email: [email protected] PL Web: www.harcourtsfourseasons.co.nz BALLINGER PLWAKEMAN WAY CRAMPTON CL LILLIAN ST BEACHVALE DR D R E D I S T S M S A C M A I KENNY LN L L To I W Rangiora GILCHRIST PL B RYDER PARK 6 SKEWBRIDGE RD North MILL RD DR I U N I G N A NGAHAU ST R JOHNSONHANCOX ST ST ADDERLEY TCE KAIAPOI E CEMETERY C T HAKARAU RD E E D E I V S A M E To Pines, A CANDY O E CRES H R B and Kairaki U T T S D C V SEWELL ST B M OHOKA RD A E 3 ISLAND RD R 35 T 5 S 7 R 34 E 20 CASS ST V WICK ST MOORE A L D D I G L R S C E AUDLEY 1 F STREET 7 GRAY CRES RESERVE B 2 23 4 B 2 9 3 8 12 18 BUTCHERS RD 8 33 5 31 1 A 11 BAKER COSGROVE RD PARK 16 CHARLES ST OHOKA RD 15 21 17 26 HALL ST 22 24 25 12 27 A 13 29 6 GILES RD 14 13 10 F 28 32 11 30 D A 10 C D JIM BRYDEN RESERVE To Christchurch E © Copyright Enterprise North Canterbury 2018 WALKING/CYCLING TRAIL 4 For information and bookings contact the Kaiapoi i-SITE Visitor Information Kaiapoi Street and Information Index Centre on 03 327 3134 Adams Street C5 Counihan Pl H4 Kaikanui St H4 Revells Rd D2 B Restaurant & Take ATTRACTIONS: F4 New World (ATM) Adderley Tce E2 Coups Tce E4 Kalmia Pl F5 Rich St F3 A Away F4 Art on the Quay Gallery/ INFORMATION & SERVICES 13 Addies Way F1 Courtenay Dr H4 Kanuka Pl F5 Robb Pl F1 1 G4 Kaikanui Tavern- Kaiapoi Museum F4 ANZ Bank (ATM) B 2 Restaurant Akaroa St G3 Crampton Close -

Waimakariri Zone Socio-Economic Profile

CANTERBURY WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY: WAIMAKARIRI ZONE SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE Prepared by Mary Sparrow for Environment Canterbury and the Waimakariri District Council INDEX EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………..i 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 WAIMAKARIRI ZONE ............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Profile ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 THE WAIMAKARIRI ZONE ................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 The Land and its History .......................................................................................................... 4 3 WAIMAKARIRI’S PEOPLE ................................................................................................................. 6 3.1 Growth and distribution ......................................................................................................... 6 3.2 Age distribution of Waimakariri’s population ....................................................................... 10 3.3 Place of residence five years ago and place of birth............................................................. 14 3.4 Ethnic identification in the Waimakariri District .................................................................. -

Health Promoting Schools Magazine, Term 2 2017

HEALTH PROMOTING SCHOOLS MAGAZINE MĀ TE TAUTOKO A TE IWI KA PŪĀWAI TE KURA He taonga rongonui te aroha ki te tangata Goodwill towards others is a precious gift Term 2 | 2017 Te Oranga / Wellbeing Traditional Ki O Rahi field opened at Mairehau High School by Kyla Dench (TIC Health Ed) and Jackson Smith (year 13 student), Hauora Council Back in 2015 the Hauora Council (student health the field looks amazing! and wellbeing committee) decided to embark on a The field was officially opened by the principal, field rejuvenation project to increase our community Mr Romana, and Whaea Dayna Napa on 7 April wellbeing, belonging, cohesion, and school pride. 2017. After the official ceremony, the last grass was At the heart of our rejuvenation project is the symbolically planted into the ground, and the first establishment of a traditional, living Ki O Rahi field, official game of Ki O Rahi was played with the Year which is a first for the whole of the South Island! 13 PE class taking on the TOA Sport team, from Ara Ki O Rahi is a traditional Māori game played with a Institute of Canterbury. small round ball called a ki. For the creation of this We are now looking to make some stone Pou that field native grasses and a rock were sourced from represent our Waka to replace the temporary the Canterbury Plains, as this is the land of Ngāi poles in the field. The next steps of the total field Tahu. A school and community working bee was rejuvenation project is the planning of fitness organised to plant the grasses, and the team had stations. -

Physical Disability Specialist Service Provider in Waimakariri District

Physical Disability Specialist Service Provider in Waimakariri District, Christchurch City, Banks Peninsula and Selwyn District Isleworth School Ph: 03 359 8553 59A Farrington Ave Fax: 03 359 8560 Bishopdale Christchurch List of schools covered by the specialist service provider (Isleworth School): Waimakariri District Ashgrove School Pegasus Bay School Ashley School Rangiora Borough School Clarkville School Rangiora High School Cust School Rangiora New Life School Fernside School St Joseph's School (Rangiora) Kaiapoi Borough School St Patrick's School (Kaiapoi) Kaiapoi High School Sefton School Kaiapoi North School Southbrook School Karanga Mai Young Parents College Swannanoa School Loburn School Tuahiwi School North Loburn School View Hill School Ohoka School West Eyreton School Oxford Area School Woodend School Christchurch City Aranui High School Our Lady of Fatima School (Chch) Avonside Girls' High School Our Lady of Assumption School (Chch) Addington School Our Lady of Victories School Aranui School (Christchurch) Ouruhia Model School Avondale School (Christchurch) Papanui High School Avonhead School Papanui School Bamford School Paparoa Street School Banks Avenue School Parkview School Beckenham School Queenspark School Belfast School Rangi Ruru Girls' School Bishopdale School Rawhiti School Breens Intermediate School Redcliffs School Bromley School Redwood School (Christchurch) Burnside High School Riccarton High School Burnside Primary School Riccarton School Canterbury Christian College Rudolf Steiner School (Christchurch) Casebrook -

Discover Waimakariri's Natural Adventure Playground

www.visitwaimakariri.co.nz KAIAPOI RANGIORA BEACHES OF WAIMAKARIRI Discover Waimakariri’s Kaiapoi river walks and cycleways Tuhaitara Coastal Park natural adventure playground (part only) Stretching from the Waimakariri River to the A fun and interesting way to explore Kaiapoi, ‘North Ashley River is an area of Canterbury’s river town’, is by cycle or on foot. You can INTRODUCTION TRACK VARIETY 580ha of coastline that is choose the route and length of your ride or walk, along the Try the variety of tracks outlined in this useful guide and under the management of The country lifestyle district of Waimakariri is based in riverbank and across the Kaiapoi river bridges. experience this district’s rich human and natural heritage – a the Te Kohaka o Tuhaitara the heartland of the South Island, only 20 minutes north 15 minutes – 1 hour. of Christchurch. diversity that encompasses mountains, forests, lakes, rivers, Trust. The Tuhaitara wetland reserves and beaches. Coastal Park is a special Richardson In this district you will discover an adventure environment that offers Mt and Glentui playground in the countryside that lies between the There are tracks for all levels of experience, fitness and ecological, educational, ability. The tracks provide access to sites with beautiful Waimakariri River, and just beyond its northern partner, cultural and recreational Area Conservation the Ashley River. panoramic views, historic, cultural or spiritual significance and opportunities for all who Forest Thomas Mt opportunities to explore the backcountry. Northbrook Wetlands visit. www.tuhaitarapark.org.nz Kairaki, Pines, Area Conservation Forest Oxford Kaiapoi Island Woodend and Waikuku Beaches The Northbrook Wetlands was once the site of early European Rivers and Beaches industry including; flax mills, a brewery, fellmongery and a Pegasus (part only) tannery. -

New Zealand Touring Map

Manawatawhi / Three Kings Islands NEW ZEALAND TOURING MAP Cape Reinga Spirits North Cape (Otoa) (Te Rerengawairua) Bay Waitiki North Island Landing Great Exhibition Kilometres (km) Kilometres (km) N in e Bay Whangarei 819 624 626 285 376 450 404 698 539 593 155 297 675 170 265 360 658 294 105 413 849 921 630 211 324 600 863 561 t Westport y 1 M Wellington 195 452 584 548 380 462 145 355 334 983 533 550 660 790 363 276 277 456 148 242 352 212 649 762 71 231 Wanaka i l Karikari Peninsula e 95 Wanganui 370 434 391 222 305 74 160 252 779 327 468 454 North Island971 650 286 508 714 359 159 121 499 986 1000 186 Te Anau B e a Wairoa 380 308 252 222 296 529 118 781 329 98 456 800 479 299 348 567 187 189 299 271 917 829 Queenstown c Mangonui h Cavalli Is Themed Highways29 350 711 574 360 717 905 1121 672 113 71 10 Thames 115 205 158 454 349 347 440 107 413 115 Picton Kaitaia Kaeo 167 86 417 398 311 531 107 298 206 117 438 799 485 296 604 996 1107 737 42 Tauranga For more information visit Nelson Ahipara 1 Bay of Tauroa Point Kerikeri Islands Cape Brett Taupo 82 249 296 143 605 153 350 280 newzealand.com/int/themed-highways643 322 329 670 525 360 445 578 Mt Cook (Reef Point) 87 Russell Paihia Rotorua 331 312 225 561 107 287 234 1058 748 387 637 835 494 280 Milford Sound 11 17 Twin Coast Discovery Highway: This route begins Kaikohe Palmerston North 234 178 853 401 394 528 876 555 195 607 745 376 Invercargill Rawene 10 Whangaruru Harbour Aotearoa, 13 Kawakawa in Auckland and travels north, tracing both coasts to 12 Poor Knights New Plymouth 412 694 242 599 369 721 527 424 181 308 Haast Opononi 53 1 56 Cape Reinga and back. -

Cluster 33 Schools List

FIRST EDUMIS Cluster Cluster School Lead number Number Cluster Name number School name School COL_NAME 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 308 Amuri Area School Tipu Maia Community of Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 309 Cheviot Area School Tipu Maia Community of Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 310 Oxford Area School Tipu Maia Community of Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 311 Hurunui College Tipu Maia Community of Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 312 Rangiora High School Puketeraki Community of Learning Katote (Christchurch) Community of 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 314 Kaiapoi High School Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 418 Rangiora New Life School Tipu Maia Community of Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 572 Te Matauru Primary School None 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 3276 Amberley School Puketeraki Community of Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 3284 Ashgrove School Puketeraki Community of Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 3285 Ashley School Puketeraki Community of Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 3303 Broomfield School Puketeraki Community of Learning Katote (Christchurch) Community of 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford 3321 Clarkville School Learning 6462 33 North Canterbury /Rangiora /Kaiapoi / Oxford