Oral History Interview with Franz Schulze, 2015 October 19-21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dan Nadel, Hairy Who? 1966-1969, Artforum, February 2019, P. 164-167 REVIEWS

ARTFORUM H A L E s GLADYS NILSSON Dan Nadel, Hairy Who? 1966-1969, Artforum, February 2019, p. 164-167 REVIEWS FOCUS 166 Dan Nadel OIi "Hall)' Who? 1966-1969 " 11:18 Barry SChwabskyon Raout de Keyser 169 Dvdu l<ekeon the 12th Shangh ai Blennale NEW YORK PARIS zoe Lescaze on Liu vu,kav11ge 186 UllianOevieson Lucla L.a&una Ania Szremski on Amar Kanwar Mart1 Hoberman on Alaln Bublex Jeff Gibson on Paulina OloW5ka BERLIN 172 Colby Chamberialn on Lorraine O'Grady 187 MartinHerberton SteveBlshop OavtdFrankelon lyleAshtonHarrl5 Jurriaan Benschopon Louise Bonnet 173 MlchaelWilsonon HelenMlrra Chloe Wyma on Leonor Finl HAMBURG R11chelChumeron HeddaS1erne JensAsthoffon UllaYonBrandenburg Mira DayalonM11rcelStorr ZURICH 176 Donald Kuspit on ltya Bolotowsky Adam Jasper on Raphaela Vogel Barry Schwabsky on Gregor Hildebrandt 2ackHatfieldon"AnnaAtklns ROME Refracted: Contemporary Works " Francesca Pola on Elger Esser Sasha Frere-Jones on Aur.i Satz TURIN.ITALY Matthew Weinstein on Allen Frame Giorglo\lerzottlon F,ancescoVeuoll WASHINGTON, DC VIENNA 179 TinaR1versRyan011 TrevorPaglen Yuki Higashinoon CHICAGO Wende1ienvanO1denborgh C.C. McKee on Ebony G. Patterson PRAGUE BrienT. Leahy on Robertlostull er 192 Noemi Smolik on Jakub Jansa LISBON 181 Kaira M. cabanas on AlexandreMeloon JuanArauJo ·co ntesting Modernity : ATHENS lnlormallsm In Venezuela, 1955-1975" 193 Cathr)TI Drakeontlle 6thAthensB lennele EL PASO,TEXAS BEIJING 1s2 Che!seaweatherson 194 F!OrlB He on Zhan, Pelll "AfterPosada : Revolutlon · YuanFucaon ZhaoYao LOS ANGELES TOKYO 183 SuzanneHudsonon Sert1Gernsbecher 195 Paige K. Bradley on Lee Kil Aney Campbell on Mary Reid KalleyandP!ltflCkKelley OUBAI GollcanDamifkaz1k on Ana Mazzei TORONTO Dan Adler on Shannon Boo! ABIOJAN, IVORY COAST 196 Mars Haberman on Ouatlera Watts LONDON Sherman Sam on Lucy Dodd SAO PAULO EJisaSchaarot1Flom1Tan Camila Belchior on Clarissa Tossln CHRISTCHURCH. -

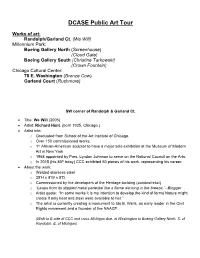

DCASE Public Art Self-Guided Tour Packet (PDF)

DCASE Public Art Tour Works of art: Randolph/Garland Ct. (We Will) Millennium Park: Boeing Gallery North (Screenhouse) (Cloud Gate) Boeing Gallery South (Christine Tarkowski) (Crown Fountain) Chicago Cultural Center: 78 E. Washington (Bronze Cow) Garland Court (Rushmore) SW corner of Randolph & Garland Ct. • Title: We Will (2005) • Artist: Richard Hunt, (born 1935, Chicago.) • Artist info: o Graduated from School of the Art Institute of Chicago. o Over 150 commissioned works. o 1st African-American sculptor to have a major solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York o 1968 appointed by Pres. Lyndon Johnson to serve on the National Council on the Arts. o In 2015 (his 80th bday) CCC exhibited 60 pieces of his work, representing his career. • About the work: o Welded stainless steel o 35’H x 8’W x 8’D o Commissioned by the developers of the Heritage building (condos/retail) o “Leaps from its stippled metal pedestal like a flame dancing in the breeze.”--Blogger o Artist quote: “In some works it is my intention to develop the kind of forms Nature might create if only heat and steel were available to her.” o The artist is currently creating a monument to Ida B. Wells, an early leader in the Civil Rights movement and a founder of the NAACP. (Walk to E side of CCC and cross Michigan Ave. at Washington to Boeing Gallery North, S. of Randolph, E. of Michigan) Millennium Park • Opened in 2004, the 24.5 acre Millennium Park was an industrial wasteland transformed into a world- class public park. -

Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, Ve Aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2013 Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Jonathan Vimr University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Vimr, Jonathan, "Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites" (2013). Theses (Historic Preservation). 211. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 Suggested Citation: Vimr, Jonathan (2013). Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Abstract Just as architectural history traditionally takes the form of a march of styles, so too do preservationists repeatedly campaign to save seminal works of an architectural manner several decades after its period of prominence. This is currently happening with New Brutalism and given its age and current unpopularity will likely soon befall postmodern historicism. In hopes of preventing the loss of any of the manner’s preeminent works, this study provides professionals with a framework for evaluating the significance of postmodern historicist designs in relation to one another. Through this, the limited resources required for large-scale preservation campaigns can be correctly dedicated to the most emblematic sites. Three case studies demonstrate the application of these criteria and an extended look at recent preservation campaigns provides lessons in how to best proactively preserve unpopular sites. -

Gladys Nilsson MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY | 523 WEST 24TH STREET

MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY 523 West 24th Street, New York,New York 10011 Tel: 212-243-0200 Fax: 212-243-0047 Gladys Nilsson MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY | 523 WEST 24TH STREET GARTH GREENAN GALLERY “Honk! Fifty Years of Painting,” an energizing, deeply satisfying pair of shows devoted to the work of Gladys Nilsson that occupied both Matthew Marks’s Twenty-Fourth Street space, where it remains on view through April 18, and Garth Greenan Gallery, took its title from one of the earliest works on display: Honk, 1964, a tiny, Technicolor street scene in acrylic that focuses on a pair of elderly couples, which the Imagist made two years out of art school. The men, bearded and stooped, lean on canes, while the women sport dark sunglasses beneath their blue-and-chartreuse beehives. They are boxed in by four more figures: Some blank-eyed and grimacing, others skulking under fedoras pulled low. The scene might suggest a vague Kastner, Jeffrey. “Gladys Nilsson.” 58, no. 8, April 2020. Artforum kind of menace were it not for the little green noisemakers dangling from the bright-red lips of the central quartet, marking them as sly revelers rather than potential victims of some unspecified mayhem. The painting’s acid palette and thickly stylized figures obviously owe a debt to Expressionism, whose lessons Nilsson thoroughly absorbed during regular museum visits in her youth, but its sensibility is more Yellow Submarine than Blaue Reiter, its grotesquerie leavened with genial good humor. The Marks portion of the show focuses primarily on the first decade of Nilsson’s career, while Greenan’s featured works made in the past few years, the two constituent parts together neatly bookending the artist’s richly varied and lamentably underappreciated oeuvre. -

Art-Related Archival Materials in the Chicago Area

ART-RELATED ARCHIVAL MATERIALS IN THE CHICAGO AREA Betty Blum Archives of American Art American Art-Portrait Gallery Building Smithsonian Institution 8th and G Streets, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20560 1991 TRUSTEES Chairman Emeritus Richard A. Manoogian Mrs. Otto L. Spaeth Mrs. Meyer P. Potamkin Mrs. Richard Roob President Mrs. John N. Rosekrans, Jr. Richard J. Schwartz Alan E. Schwartz A. Alfred Taubman Vice-Presidents John Wilmerding Mrs. Keith S. Wellin R. Frederick Woolworth Mrs. Robert F. Shapiro Max N. Berry HONORARY TRUSTEES Dr. Irving R. Burton Treasurer Howard W. Lipman Mrs. Abbott K. Schlain Russell Lynes Mrs. William L. Richards Secretary to the Board Mrs. Dana M. Raymond FOUNDING TRUSTEES Lawrence A. Fleischman honorary Officers Edgar P. Richardson (deceased) Mrs. Francis de Marneffe Mrs. Edsel B. Ford (deceased) Miss Julienne M. Michel EX-OFFICIO TRUSTEES Members Robert McCormick Adams Tom L. Freudenheim Charles Blitzer Marc J. Pachter Eli Broad Gerald E. Buck ARCHIVES STAFF Ms. Gabriella de Ferrari Gilbert S. Edelson Richard J. Wattenmaker, Director Mrs. Ahmet M. Ertegun Susan Hamilton, Deputy Director Mrs. Arthur A. Feder James B. Byers, Assistant Director for Miles Q. Fiterman Archival Programs Mrs. Daniel Fraad Elizabeth S. Kirwin, Southeast Regional Mrs. Eugenio Garza Laguera Collector Hugh Halff, Jr. Arthur J. Breton, Curator of Manuscripts John K. Howat Judith E. Throm, Reference Archivist Dr. Helen Jessup Robert F. Brown, New England Regional Mrs. Dwight M. Kendall Center Gilbert H. Kinney Judith A. Gustafson, Midwest -

Art and Economics in the City

Caterina Benincasa, Gianfranco Neri, Michele Trimarchi (eds.) Art and Economics in the City Urban Studies Caterina Benincasa, art historian, is founder of Polyhedra (a nonprofit organi- zation focused on the relationship between art and science) and of the Innovate Heritage project aimed at a wide exchange of ideas and experience among scho- lars, artists and pratictioners. She lives in Berlin. Gianfranco Neri, architect, teaches Architectural and Urban Composition at Reggio Calabria “Mediterranea” University, where he directs the Department of Art and Territory. He extensively publishes books and articles on issues related to architectural projects. In 2005 he has been awarded the first prize in the international competition for a nursery in Rome. Michele Trimarchi (PhD), economist, teaches Public Economics (Catanzaro) and Cultural Economics (Bologna). He coordinates the Lateral Thinking Lab (IED Rome), is member of the editoral board of Creative Industries Journal and of the international council of the Creative Industries Federation. Caterina Benincasa, Gianfranco Neri, Michele Trimarchi (eds.) Art and Economics in the City New Cultural Maps An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-4214-2. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.know- ledgeunlatched.org. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. -

Gladys Nilsson Featured in the New York Times

http://nyti.ms/1n3sZC4 ART & DESIGN | ART REVIEW Recognizing a Vibrant Underground ‘What Nerve!’ at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum By KEN JOHNSON SEPT. 25, 2014 In 1962 the film critic Manny Farber published the provocative essay “White Elephant Art and Termite Art,” in which he distinguished two types of artists: the White Elephant artist, who tries to create masterpieces equal to the greatest artworks of the past, and the Termite, who engages in “a kind of squandering- beaverish endeavor” that “goes always forward, eating its own boundaries and, likely as not, leaves nothing in its path other than signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.” While White Elephant artists like Richard Serra, Brice Marden, Jeff Koons and a few other usually male contemporary masters still are most highly valued by the establishment, the art world’s Termite infestation has grown exponentially. They’re everywhere, male and female, busily burrowing in a zillion directions. They’re painting, drawing, doodling, whittling, tinkering and making comic books, zines, animated videos and Internet whatsits — all, it seems, with no objective other than to just keep doing whatever they’re doing. Where did they come from? How did this happen? The history of White Elephant art is well known, that of Termite art much less so, which isn’t surprising given its furtive, centerless nature. So it’s gratifying to see a rousing exhibition at the Rhode Island School of Design Museum that blocks out a significant part of what such a history would entail. “What Nerve! Alternative Figures in American Art, 1960 to the Present” presents more than 180 paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, photographs and videos by 29 artists whom Mr. -

A Finding Aid to the Ellen Lanyon Papers, Circa 1880-2014, Bulk 1926-2013, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Ellen Lanyon Papers, circa 1880-2014, bulk 1926-2013, in the Archives of American Art Hilary Price 2016 September 19 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1880-2015 (bulk 1926-2015)......................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1936-2015.................................................................. 10 Series 3: Interviews, circa 1975-2012.................................................................... 24 Series 4: Writings, Lectures, and Notebooks, circa -

The Crown Fountain in Chicago's Millennium Park Is an Ingenious

ACrowning Achievement The Crown Fountain in Chicago’s Millennium Park is an ingenious fusion of artistic vision and high-tech water effects in which sculptor Jaume Plensa’s creative concepts were brought to life by an interdisciplinary team that included the waterfeature designers at Crystal Fountains. Here, Larry O’Hearn describes how the firm met the challenge and helped give Chicago’s residents a defining landmark in glass, light, water and bright faces. 50 WATERsHAPES ⅐ APRIL 2005 ByLarry O’Hearn In July last year, the city of Chicago unveiled its newest civic landmark: Millennium Park, a world-class artistic and architec- tural extravaganza in the heart of downtown. At a cost of more than $475 million and in a process that took more than six years to complete, the park transformed a lakefront space once marked by unsightly railroad tracks and ugly parking lots into a civic showcase. The creation of the 24.5-acre park brought together an unprecedented collection of world-class artists, architects, urban planners, landscape architects and designers including Frank Gehry, Anish Kapoor and Kathryn Gustafson. Each con- tributed unique designs that make powerful statements about the ambition and energy that define Chicago. One of the key features of Millennium Park is the Crown Fountain. Designed by Jaume Plensa, the Spanish- born sculptor known for installations that focus on human experiences that link past, present and fu- ture and for a philosophy that says art should not simply decorate an area but rather should trans- form and regenerate it, the Crown Fountain began with the notion that watershapes such as this one need to be gathering places. -

LHAT 40Th Anniversary National Conference July 17-20, 2016

Summer 2016 Vol. 39 No. 2 IN THE LEAGUE OF HISTORIC AMERICAN THEATRES LEAGUE LHAT 40th Anniversary National Conference 9 Newport Drive, Ste. 200 Forest Hill, MD 21050 July40th 17-20, ANNUAL 2016 (T) 443.640.1058 (F) 443.640.1031 WWW.LHAT.ORG CONFERENCE & THEATRE TOUR ©2016 LEAGUE OF HISTORIC AMERICAN THEATRES. Chicago, IL ~ JULY17-20, 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Greetings from Board Chair, Jeffery Gabel 2016 Board of Directors On behalf of your board of directors, welcome to Chicago and the L Dana Amendola eague of Historic American Theatres’ 40th Annual Conference Disney Theatrical Group and Theatre Tour. Our beautiful conference hotel is located in John Bell the heart of Chicago’s historic theatre district which has seen FROM it all from the rowdy heydays of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show to Tampa Theatre Randy Cohen burlesque and speakeasies to the world-renowned Lyric Opera, Americans for the Arts Steppenwolf Theatre and Second City. John Darby The Shubert Organization, Inc. I want to extend an especially warm welcome to those of you Michael DiBlasi, ASTC who are attending your first LHAT conference. You will observe old PaPantntaggeses Theh attrer , LOL S ANANGGELEL S Schuler Shook Theatre Planners friends embracing as if this were some sort of family reunion. That’s COAST Molly Fortune because, for many, LHAT is a family whose members can’t wait Newberry Opera House to catch up since last time. It is a family that is always welcoming Jeffrey W. Gabel new faces with fresh ideas and even more colorful backstage Majestic Theater stories. -

Karl Wirsum B

Karl Wirsum b. 1939 Lives and works in Chicago, IL Education 1961 BFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL Solo Exhibitions 2019 Unmixedly at Ease: 50 Years of Drawing, Derek Eller Gallery, NY Karl Wirsum, Corbett vs Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2018 Drawing It On, 1965 to the Present, organized by Dan Nadel and Andreas Melas, Martinos, Athens, Greece 2017 Mr. Whatzit: Selections from the 1980's, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY No Dogs Aloud, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2015 Karl Wirsum, The Hard Way: Selections from the 1970s, Organized with Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Drawings: 1967-70, co-curated by Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2008 Karl Wirsum: Paintings & Prints, Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, Peoria, IL Winsome Works(some), Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL; traveled to Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI; Herron Galleries, Indiana University- Perdue University, Indianapolis, IN 2007 Karl Wirsum: Plays Missed It For You, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2006 The Wirsum-Gunn Family Show, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2005 Union Art Gallery, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 2004 Hello Again Boom A Rang: Ten Years of Wirsum Art, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2002 Paintings and Cutouts, Quincy Art Center, Quincy, IL Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2001 Rockford College Gallery, Rockford, IL 2000 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 1998 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL University Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1997 The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Sculpture Court, Iowa City, IA 1994 Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, IL J. -

JIM NUTT by David St.-Lascaux

JULY / AUGUST 2010 JIM NUTT by David St.-Lascaux Jim Nutt is back in New York, sans straightjacket. Once a wildman, he was part of Chicago’s Imagist/Hairy Who movement, back in ’66 when Hairy meant huge, when Ed “Big Daddy” Roth was customizing petroleum-powered hot rods with giant ratfinks, chrome pipes, metalflake paint jobs and two-tone flames, shortly after which S. Clay Wilson introduced the maniacal Checkered Demon and the ravishing Star-Eyed Stella. Meanwhile, in New York, the influential, serious works created by Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, Rosenquist, and Warhol—also influenced by commercial imagery—were being digested. And what a contrast, using the same cultural raw materials: the Midwest output infantile, maybe; the East Coast oeuvre just possibly uptight. The Hairy Who included graduates of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago: James Falconer; Art Green; Gladys Nilsson, now Nutt’s wife; Suellen Rocca and Karl Wirsum, an Adolf Wölfli doppelgänger. Members of the Imagist movement included Roger Brown, Leon Golub, Ed Paschke (Jeff Koons, then a student, his assistant), Nancy Spero, and H.C. Westermann. The movement’s work was of its time: cartoon garish, rude, clever, heavy on wordplay and sexual innuendo. Hell, it was entirely explicit, and, as demonstrated in Nutt’s “There are Reasons” (1974), in which a Sadie Hawkins Day predacious Jane chases a ragged Dick across a stage, equal opportunity misandristic and misogynistic—although the snood in “Hold Still!! (Please)” (1980-1) is just a wee bit much. The work was also “representational” in the sense that Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is representational: you can decipher it.