Dupaningan Agta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Tagalog Author: Valeria Malabonga

Heritage Voices: Language - Tagalog Author: Valeria Malabonga About the Tagalog Language Tagalog is a language spoken in the central part of the Philippines and belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian language family. Tagalog is one of the major languages in the Philippines. The standardized form of Tagalog is called Filipino. Filipino is the national language of the Philippines. Filipino and English are the two official languages of the Philippines (Malabonga & Marinova-Todd, 2007). Within the Philippines, Tagalog is spoken in Manila, most of central Luzon, and Palawan. Tagalog is also spoken by persons of Filipino descent in Canada, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States. In the United States, large numbers of Filipino immigrants live in California, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Texas, and Washington (Camarota & McArdle, 2003). According to the 2000 US Census, Tagalog is the sixth most spoken language in the United States, spoken by over a million speakers. There are about 90 million speakers of Tagalog worldwide. Bessie Carmichael Elementary School/Filipino Education Center in San Francisco, California is the only elementary school in the United States that has an English-Tagalog bilingual program (Guballa, 2002). Tagalog is also taught at two high schools in California. It is taught as a subject at James Logan High School, in the New Haven Unified School District (NHUSD) in the San Francisco Bay area (Dizon, 2008) and as an elective at Southwest High School in the Sweetwater Union High School District of San Diego. At the community college level, Tagalog is taught as a second or foreign language at Kapiolani Community College, Honolulu Community College, and Leeward Community College in Hawaii and Sacramento City College in California. -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Tagalog As Spoken In

Language specific peculiarities Document for Tagalog as Spoken in the Philippines 1. Dialects Tagalog is spoken by around 25 million1 people as a first language and approximately 60 million as a second language. It is the local language spoken by most Filipinos and serves as a lingua franca in most parts of the Philippines. It is also the de facto national language of the Philippines together with English. Although officially the name of the national language is "Filipino", which has Tagalog as its basis, the majority of Filipinos are unaccustomed, even unaware, of this naming convention. Practically speaking, the name "Tagalog" is used by many Filipinos when referring to the national language. "Filipino", on the other hand, is rather ambiguous and, it must be said, carries nationalistic overtones2. The population of Tagalog native speakers is primarily concentrated in a region that covers southern Luzon and nearby islands. In this project, three major dialectal regions of Tagalog will be presented: Dialectal Region Description North Includes the Tagalog spoken in Bulacan, Bataan, Nueva Ecija and parts of Zambales. Central The Tagalog spoken in Manila, parts of Rizal and Laguna. This is the Tagalog dialect that is understood by the majority of the population. South Characteristic of the Tagalog spoken in Batangas, parts of Cavite, major parts of Quezon province and the coastal regions of the island of Mindoro. 1.1. English Influence The standard Tagalog spoken in Manila, the capital of the Philippines, is also considered the prestige dialect of Tagalog. It is the Tagalog used in the media and is taught in schools. -

A Domestication Strategy of Indigenous Premium Timber Species by Smallholders in Central Visayas and Northern Mindanao, the Philippines

A DOMESTICATION STRATEGY OF INDIGENOUS PREMIUM TIMBER SPECIES BY SMALLHOLDERS IN CENTRAL VISAYAS AND NORTHERN MINDANAO, THE PHILIPPINES Autor: Iria Soto Embodas Supervisors: Hugo de Boer and Manuel Bertomeu Garcia Department: Systematic Botany, Uppsala University Examyear: 2007 Study points: 20 p Table of contents PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. CONTEXT OF THE STUDY AND RATIONALE 3 3. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY 18 4. ORGANIZATION OF THE STUDY 19 5. METHODOLOGY 20 6. RESULTS 28 7. DISCUSSION: CURRENT CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR DOMESTICATING PREMIUM TIMBER SPECIES 75 8. TOWARDS REFORESTATION WITH PREMIUM TIMBER SPECIES IN THE PHILIPPINES: A PROPOSAL FOR A TREE 81 DOMESTICATION STRATEGY 9. REFERENCES 91 1. INTRODUCTION The importance of the preservation of the tropical rainforest is discussed all over the world (e.g. 1972 Stockholm Conference, 1975 Helsinki Conference, 1992 Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, and the 2002 Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development). Tropical rainforest has been recognized as one of the main elements for maintaining climatic conditions, for the prevention of impoverishment of human societies and for the maintenance of biodiversity, since they support an immense richness of life (Withmore, 1990). In addition sustainable management of the environment and elimination of absolute poverty are included as the 21 st Century most important challenges embedded in the Millennium Development Goals. The forest of Southeast Asia constitutes, after the South American, the second most extensive rainforest formation in the world. The archipelago of tropical Southeast Asia is one of the world's great reserves of biodiversity and endemism. This holds true for The Philippines in particular: it is one of the most important “biodiversity hotspots” .1. -

Responses of 'Carabao' Mango to Various Ripening Agents

Philippine Journal of Science 148 (3): 513-523, September 2019 ISSN 0031 - 7683 Date Received: 08 Apr 2019 Responses of ‘Carabao’ Mango to Various Ripening Agents Angelyn T. Lacap1, Emma Ruth V. Bayogan1*, Leizel B. Secretaria1, Christine Diana S. Lubaton1, and Daryl C. Joyce2,3 1College of Science and Mathematics, University of the Philippines Mindanao, Mintal, Tugbok District, Davao City 8022 Philippines 2School of Agriculture and Food Sciences, The University of Queensland, Gatton, QLD 4343 Australia 3Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Ecosciences Precinct, Dutton Park, QLD 4102 Australia Calcium carbide (CaC2) reacts with moisture in the air to produce acetylene (C2H2) gas, an analog of ethylene (C2H4). Commercial sources of CaC2 may be contaminated with arsenic and phosphorous, which are also released during a chemical reaction. This constitutes a potentially serious health risk to ripeners and may contaminate the product. Although banned in many countries, CaC2 is still used in the Philippines because equally inexpensive and effective alternatives are lacking. This study investigated the relative efficacy of alternatives for ripening ‘Carabao’ mango. Fruit harvested at –1 107 d after flower induction were treated with CaC2 (2.5, 5.0, or 7.5 g kg ); ethephon (500, 1000, or 1500 μL L–1); Gliricidia sepium leaves (20% w/w); or ‘Cardava’ banana fruit (10% w/w) for 72 h. Mangoes were then held under ambient room conditions [29.9 ± 3.1°C, 77.74 ± 2.9% relative humidity (RH)] for 7 d. Assessments of peel color, firmness, and total soluble solids showed that fruit treated with higher concentrations of ethephon (1000 or 1500 μL L–1) exhibited similar ripening –1 responses as those treated with CaC2. -

Human Noun Pluralization in Northern Luzon Languages

Streams Converging Into an Ocean, 49-69 2006-8-005-003-000081-1 Human Noun Pluralization in Northern Luzon Languages Lawrence A. Reid University of Hawai‘i This paper describes some of the derivational processes by which human nouns are pluralized in some of the Northern Luzon, or Cordilleran, languages of the Philippines. Although primarily descriptive, it offers intriguing insights into the ways reduplicative processes have changed as a result of the application of regular sound changes in some of the daughter languages of the family. Key words: reduplication, geminates, plural human nouns, Philippine languages, Northern Luzon, Cordilleran 1. Plural human nouns in Proto-Northern Luzon It is a great pleasure for me to be able to offer this paper in honor of Professor Paul Jen-kuei Li, one of the most productive linguists working on the Austronesian languages of Taiwan. I have known Paul since his student days at the University of Hawai‘i many decades ago, and have treasured his friendship and respected the quality of his scholarship ever since. In all Northern Luzon languages, most common nouns can be interpreted as either singular or plural, with plurality being marked either by an accompanying pluralizing nominal form, typically a plural demonstrative or a third person plural pronoun. Most if not all languages, however, have a small class of nouns which have plural forms. This class usually includes common kinship terms such as ‘father’, ‘mother’, ‘child’, ‘sibling’, and ‘grandparent’ or ‘grandchild’. Proto-Northern Luzon probably also had plural forms for these nouns. In many of the daughter languages other human nouns, such as ‘man’, ‘woman’, ‘young man’, ‘young woman’, ‘spouse’, etc., are also pluralizable, either because already by Proto-Northern Luzon the process had been generalized to include such forms, or the generalization has taken place since then. -

A Compilation and Analysis of Food Plants Utilization of Sri Lankan Butterfly Larvae (Papilionoidea)

MAJOR ARTICLE TAPROBANICA, ISSN 1800–427X. August, 2014. Vol. 06, No. 02: pp. 110–131, pls. 12, 13. © Research Center for Climate Change, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia & Taprobanica Private Limited, Homagama, Sri Lanka http://www.sljol.info/index.php/tapro A COMPILATION AND ANALYSIS OF FOOD PLANTS UTILIZATION OF SRI LANKAN BUTTERFLY LARVAE (PAPILIONOIDEA) Section Editors: Jeffrey Miller & James L. Reveal Submitted: 08 Dec. 2013, Accepted: 15 Mar. 2014 H. D. Jayasinghe1,2, S. S. Rajapaksha1, C. de Alwis1 1Butterfly Conservation Society of Sri Lanka, 762/A, Yatihena, Malwana, Sri Lanka 2 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Larval food plants (LFPs) of Sri Lankan butterflies are poorly documented in the historical literature and there is a great need to identify LFPs in conservation perspectives. Therefore, the current study was designed and carried out during the past decade. A list of LFPs for 207 butterfly species (Super family Papilionoidea) of Sri Lanka is presented based on local studies and includes 785 plant-butterfly combinations and 480 plant species. Many of these combinations are reported for the first time in Sri Lanka. The impact of introducing new plants on the dynamics of abundance and distribution of butterflies, the possibility of butterflies being pests on crops, and observations of LFPs of rare butterfly species, are discussed. This information is crucial for the conservation management of the butterfly fauna in Sri Lanka. Key words: conservation, crops, larval food plants (LFPs), pests, plant-butterfly combination. Introduction Butterflies go through complete metamorphosis 1949). As all herbivorous insects show some and have two stages of food consumtion. -

(0399912) Establishing Baseline Data for the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole, Philippines

ORIS Project (0399912) Establishing Baseline Data for the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole, Philippines Joni T. Acay and Nikki Dyanne C. Realubit In cooperation with: Page | 0 ORIS Project CLP PROJECT ID (0399912) Establishing Baseline Data for the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole, Philippines PROJECT LOCATION AND DURATION: Luzon Island, Philippines Provinces of Bataan, Quirino, Isabela and Cagayan August 2012-July 2014 PROJECT PARTNERS: ∗ Mabuwaya Foundation Inc., Cabagan, Isabela ∗ Department of Natural Sciences (DNS) and Department of Development Communication and Languages (DDCL), College of Development Communication and Arts & Sciences, ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY-Cabagan, ∗ Wild Bird Club of the Philippines (WBCP), Manila ∗ Community Environmental and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) Aparri, CENRO Alcala, Provincial Enviroment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO) Cagayan ∗ Protected Area Superintendent (PASu) Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, CENRO Naguilian, PENRO Isabela ∗ PASu Quirino Protected Landscape, PENRO Quirino ∗ PASu Mariveles Watershed Forest Reserve, PENRO Bataan ∗ Municipalities of Baggao, Gonzaga, San Mariano, Diffun, Limay and Mariveles PROJECT AIM: Generate baseline information for the conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole. PROJECT TEAM: Joni Acay, Nikki Dyanne Realubit, Jerwin Baquiran, Machael Acob Volunteers: Vanessa Balacanao, Othniel Cammagay, Reymond Guttierez PROJECT ADDRESS: Mabuwaya Foundation, Inc. Office, CCVPED Building, ISU-Cabagan Campus, -

Presenting Affiliations with Adresses MPSD - 01 Adopting Blueprints of Nature: Marine Waste-Derived Jolleen Natalie I

SCIENTIFIC POSTERS - LIST OF ACCEPTED ABSTRACTS - MATHEMATICS AND PHYSICAL SCIENCES No. Title of Abstract (Please do not use All Caps.) Names of authors Major Author - Presenting Affiliations with Adresses MPSD - 01 Adopting blueprints of nature: Marine waste-derived Jolleen Natalie I. Jolleen Natalie Jolleen Natalie The Graduate School self-healing hydrogels for wound healing Balitaan, Chung-Der Balitaan Balitaan and Department of Hsiao, Jui-Ming Yeh, Chemistry, College of Karen S. Santiago Science University of Santo Tomas, España Boulevard, Manila 1008 MPSD - 02 Antioxidant Activity of Total Carotenoids Extracted Arvin Paul P. Tuaño, Arvin Paul P. Arvin Paul P. Institute of Human from Lemon Peels via Dual Enzyme-Assisted Audrey Dana F. Tuaño Tuaño Nutrition and Food, Extraction using Microbial Xylanase and Cellulase Domingo, and Vyanka College of Human Teia Leeniza M. Gonzales Ecology, University of the Philippines Los Baños, College, Laguna; Department of Biochemistry, College of Humanities and Sciences, De La Salle Medical and Health Sciences Institute, Dasmariñas, Cavite MPSD - 03 Aromatic Ether Bond Cleavage of Lignin Model Mormie Joseph F. Sarno, Mormie Joseph Mormie Joseph Adventist University of Compound (Benzyl Phenyl Ether) Utilizing Cobalt- Allan Jay P. Cardenas, F. Sarno F. Sarno the Philippines PDI Complexes Mae Joanne B. Aguila MPSD - 04 Biocompatible and Antimicrobial Cellulose Acetate Carlo M. Macaspag, Jenneli E. Caya Carlo M. Philippine Textile Nanofiber Membrane from Banana (Musa Jenneli E. Caya Macaspag Research Institute, Gen. acuminata x balbisiana) Pseudostem Fibers. Santos Ave., Bicutan, Taguig City 1631 MPSD - 05 Citric Acid Crosslinked Nanofibrillated Cellulose Jared Vincent T. Josanelle Jared Vincent T. Philippine Textile from Banana (Musa acuminata x balbisiana) Lacaran, Ronald Angela V. -

Documentation of Northern Alta: Grammar, Texts and Glossary

Documentation of Northern Alta: grammar, texts and glossary Alexandro-Xavier García Laguía ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tdx.cat) i a través del Dipòsit Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX ni al Dipòsit Digital de la UB. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX o al Dipòsit Digital de la UB (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tdx.cat) y a través del Repositorio Digital de la UB (diposit.ub.edu) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR o al Repositorio Digital de la UB. -

Cagayan Riverine Zone Development Framework Plan 2005—2030

Cagayan Riverine Zone Development Framework Plan 2005—2030 Regional Development Council 02 Tuguegarao City Message The adoption of the Cagayan Riverine Zone Development Framework Plan (CRZDFP) 2005-2030, is a step closer to our desire to harmonize and sustainably maximize the multiple uses of the Cagayan River as identified in the Regional Physical Framework Plan (RPFP) 2005-2030. A greater challenge is the implementation of the document which requires a deeper commitment in the preservation of the integrity of our environment while allowing the development of the River and its environs. The formulation of the document involved the wide participation of concerned agencies and with extensive consultation the local government units and the civil society, prior to its adoption and approval by the Regional Development Council. The inputs and proposals from the consultations have enriched this document as our convergence framework for the sustainable development of the Cagayan Riverine Zone. The document will provide the policy framework to synchronize efforts in addressing issues and problems to accelerate the sustainable development in the Riverine Zone and realize its full development potential. The Plan should also provide the overall direction for programs and projects in the Development Plans of the Provinces, Cities and Municipalities in the region. Let us therefore, purposively use this Plan to guide the utilization and management of water and land resources along the Cagayan River. I appreciate the importance of crafting a good plan and give higher degree of credence to ensuring its successful implementation. This is the greatest challenge for the Local Government Units and to other stakeholders of the Cagayan River’s development. -

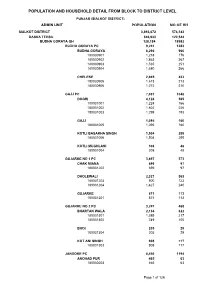

Sialkot Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH SIALKOT DISTRICT 3,893,672 574,143 DASKA TEHSIL 846,933 122,544 BUDHA GORAYA QH 128,184 18982 BUDHA GORAYA PC 9,241 1383 BUDHA GORAYA 6,296 960 180030901 1,218 176 180030902 1,863 267 180030903 1,535 251 180030904 1,680 266 CHELEKE 2,945 423 180030905 1,673 213 180030906 1,272 210 GAJJ PC 7,031 1048 DOGRI 4,124 585 180031001 1,224 166 180031002 1,602 226 180031003 1,298 193 GAJJ 1,095 160 180031005 1,095 160 KOTLI BASAKHA SINGH 1,504 255 180031006 1,504 255 KOTLI MUGHLANI 308 48 180031004 308 48 GUJARKE NO 1 PC 3,897 573 CHAK MIANA 699 97 180031202 699 97 DHOLEWALI 2,327 363 180031203 900 123 180031204 1,427 240 GUJARKE 871 113 180031201 871 113 GUJARKE NO 2 PC 3,247 468 BHARTAN WALA 2,134 322 180031301 1,385 217 180031302 749 105 BHOI 205 29 180031304 205 29 KOT ANI SINGH 908 117 180031303 908 117 JANDOKE PC 8,450 1194 ANOHAD PUR 465 63 180030203 465 63 Page 1 of 126 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JANDO KE 2,781 420 180030206 1,565 247 180030207 1,216 173 KOTLI DASO SINGH 918 127 180030204 918 127 MAHLE KE 1,922 229 180030205 1,922 229 SAKHO KE 2,364 355 180030201 1,250 184 180030202 1,114 171 KANWANLIT PC 16,644 2544 DHEDO WALI 6,974 1092 180030305 2,161 296 180030306 1,302 220 180030307 1,717 264 180030308 1,794 312 KANWAN LIT 5,856 854 180030301 2,011 290 180030302 1,128 156 180030303 1,393 207 180030304 1,324 201 KOTLI CHAMB WALI