National Gallery of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karl Wirsum B

Karl Wirsum b. 1939 Lives and works in Chicago, IL Education 1961 BFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL Solo Exhibitions 2019 Unmixedly at Ease: 50 Years of Drawing, Derek Eller Gallery, NY Karl Wirsum, Corbett vs Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2018 Drawing It On, 1965 to the Present, organized by Dan Nadel and Andreas Melas, Martinos, Athens, Greece 2017 Mr. Whatzit: Selections from the 1980's, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY No Dogs Aloud, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2015 Karl Wirsum, The Hard Way: Selections from the 1970s, Organized with Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Drawings: 1967-70, co-curated by Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2008 Karl Wirsum: Paintings & Prints, Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, Peoria, IL Winsome Works(some), Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL; traveled to Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI; Herron Galleries, Indiana University- Perdue University, Indianapolis, IN 2007 Karl Wirsum: Plays Missed It For You, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2006 The Wirsum-Gunn Family Show, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2005 Union Art Gallery, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 2004 Hello Again Boom A Rang: Ten Years of Wirsum Art, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2002 Paintings and Cutouts, Quincy Art Center, Quincy, IL Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2001 Rockford College Gallery, Rockford, IL 2000 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 1998 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL University Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1997 The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Sculpture Court, Iowa City, IA 1994 Phyllis Kind Gallery, Chicago, IL J. -

Roger Brown, a Leading Painter of the Chicago

Roger Brown, 55, Leading Chicago Imagist Painter, Dies Roberta Smith November 26, 1997 THE NEW YORK TIMES Roger Brown, a leading painter of the Chicago Imagist style, whose radiant, panoramic images were as passionately po- litical as they were rigorously visual, died on Saturday at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta. He was 55 and had homes and studios in Chicago, New Buffalo, Mich., and Carpen- teria, Calif. The cause was liver failure after a long illness, said Phyllis Kind of the Phyllis Kind Gallery, which has represented Mr. Brown since 1970. In the late 1960’s and early 70’s, Mr. Brown was one of a number of artists whose interests and talents coalesced into one of the defining moments in postwar Chicago art. The inspiration for these artists came from European Surrealism, which was prevalent in the city’s public and private collections; contemporary outsider art, which the Imagists helped promote, and popular culture, recently sanctioned by Pop Artists. In addition to Mr. Brown, these artists included Jim Nutt, Ed Paschke, Phil Hanson, Ray Yoshida, Karl Wirsum, Barbara Rossi and Gladys Nilsson, almost all of whom he met as a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and each of whom braided the city’s disparate cultural strands into a distinctive hybrid of figurative styles. Mr. Brown’s hybrid was a powerful combination of flattened, cartoonish images that featured isometric skyscrapers and tract houses, furrowed fields, undulating hills, pillowy clouds and agitated citizens, the latter usually seen in black silhouette at stark yellow windows where they enacted violent or sexual shadow plays. -

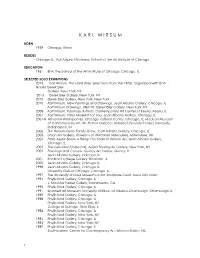

K a R L W I R S

K A R L W I R S U M BORN 1939 Chicago, Illinois RESIDES Chicago, IL Full Adjunct Professor, School of the Art Institute of Chicago EDUCATION 1961 BFA, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 Karl Wirsum, The Hard Way: Selections from the 1970s, Organized with Dan Nadel, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, New York 2010 Karl Wirsum: New Paintings and Drawings, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL Karl Wirsum Drawings: 1967-70, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2008 Karl Wirsum: Paintings & Prints, Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, Peoria, IL 2007 Karl Wirsum: Plays Missed It For You, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2007-8 Winsome Works(some), Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, IL; Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI; Herron Galleries, Indiana University-Perdue University, Indianapolis, IN 2006 The Wirsum-Gunn Family Show, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2005 Union Art Gallery, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 2004 Hello Again Boom A Rang: Ten Years of Wirsum Art, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2003 The Ganzfeld (Unbound), Adam Baumgold Gallery, New York, NY 2002 Paintings and Cutouts, Quincy Art Center, Quincy, IL Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2001 Rockford College Gallery, Rockford, IL 2000 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 1998 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL University Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1997 The University of Iowa Museum of Art, Sculpture Court, Iowa City, Iowa 1994 Phyllis Kind Gallery, -

Oral History Interview with Phyllis Kind, 2007 March 28-May 11

Oral history interview with Phyllis Kind, 2007 March 28-May 11 Funded by Widgeon Point Charitable Foundation. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Phyllis Kind on March 27, 2008. The interview took place in Kind's home in New York City, and was conducted by James McElhinney for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JAMES MCELHINNEY: Hello? Testing, testing, testing. [Audio Break.] JAMES MCELHINNEY: I think we're rolling. This is James McElhinney interviewing Phyllis Kind at—your home? Your gallery? PHYLLIS KIND: My home. JAMES MCELHINNEY: Your home, at— PHYLLIS KIND: Would you like to remember the address? JAMES MCELHINNEY: I'm trying to—440 West 22nd Street, in New York— PHYLLIS KIND: That's it. JAMES MCELHINNEY: —on the 28th of March for the Archives of American Arts Smithsonian Institution, disc number one. Well, we appear to be in business as far as the interview goes. So where and—where were you born? You don't have to say when. PHYLLIS KIND: I was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1933, at Beth Israel Hospital. JAMES MCELHINNEY: Hour? Do you know when? PHYLLIS KIND: At 8 a.m. in the morning on the 1st of April which, as you know, is some sort of special day, which I thought was invented for myself, thank you. -

Moma ANNOUNCES JOSEPH YOAKUM: WHAT I SAW, the ARTIST’S FIRST MAJOR MUSEUM EXHIBITION in OVER 25 YEARS

MoMA ANNOUNCES JOSEPH YOAKUM: WHAT I SAW, THE ARTIST’S FIRST MAJOR MUSEUM EXHIBITION IN OVER 25 YEARS Exhibition Brings Together Over 100 Drawings, Highlighting Yoakum’s Prolific Career and Unique Visual Language NEW YORK, MAY 11, 2021 — The Museum of Modern Art announces Joseph Yoakum: What I Saw, the first major museum exhibition of the artist’s work in over 25 years, on view at MoMA from November 28, 2021, through March 19, 2022. At age 71, Joseph Yoakum (1891–1972) began making idiosyncratic, poetic landscape drawings of the places he had traveled over the course of his life, creating some 2,000 extraordinary works that bear little resemblance to the world we know. This exhibition is comprised of over 100 of those works, predominantly from the collections of the artists in Chicago who knew him and admired and supported his work. Joseph Yoakum: What I Saw is organized by Esther Adler, Associate Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints, MoMA; Mark Pascale, Janet and Craig Duchossois Curator of Prints and Drawings, The Art Institute of Chicago; and Édouard Kopp, John R. Eckel, Jr. Foundation Chief Curator, Menil Drawing Institute, Houston. The exhibition will be on view at the Art Institute of Chicago from June 12 through Oct 18, 2021, and following its MoMA presentation it will travel to the Menil Collection, Houston, where it will be on view from April 22 through August 7, 2022. Yoakum was born in Ash Grove, Missouri (despite his own later claim that Window Rock, Arizona, was his birthplace) just 25 years after the end of the Civil War. -

Fall / Winter 2018 JUST GO SEE IT

Fall / Winter 2018 JUST GO SEE IT Use this guide to explore Art Design Chicago offerings throughout the city and beyond. Whatever catches Visit your interest, we encourage Art Design Chicago’s you to #JustGoSeeIt. information and activity space: Visit ArtDesignChicago.org for the most up-to-date Chicago Cultural Center information and a 78 East Washington Street full calendar of events. 1st Floor, North Entrance Note: Program information is subject See the city map on page 29. to change. Exhibitions and events that are free of charge are indicated as such; all others have an admission fee or request an optional donation. Art Design Chicago, an initiative of the Terra Foundation EXHIBITIONS for American Art, is a spirited celebration of the 2 unique and vital role Chicago plays as America’s crossroads of creativity and commerce. Throughout 2018, EXHIBITIONS Art Design Chicago presents a dynamic convergence BEYOND CHICAGO of more than 30 exhibitions and hundreds of public 18 programs, along with publications, conferences, and symposia. Together, they tell the stories of the artists and designers who defined and continue to propel PROGRAMS & EVENTS Chicago’s role as a hub of imagination and impact. 20 From art displayed on museum walls to mass-produced GALLERIES & MORE consumer goods, Chicago’s singular creative contributions 26 are showcased in this citywide partnership of more than 75 museums, art centers, universities, and other cultural organizations both large and small. MAPS 28 May 12–Oct 28, 2018 Never a Lovely So Real: Photography and Film in Chicago, 1950–1980 Art Institute of Chicago 111 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago 312.443.3600 This exhibition looks at artists who worked across Chicago from the 1950s through the 1970s and commented in EXHIBITIONS images and film on the life of the com- munities to which they belonged or were granted intimate access as outsiders. -

Karl Wirsum CV

Karl Wirsum b. 1939, Chicago, IL Lives and works in Chicago, IL Education 1961 BFA, School of the Art Institute of Chicago Professional Full Adjunct Professor, School of the Art Institute of Chicago Solo Exhibitions 2019 Unmixedly at Ease: 50 Years of Drawing, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY Karl Wirsum, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2018 Drawing It On, 1965 to the Present, organized by Dan Nadel and Andreas Melas, Martinos, Athens, Greece 2017 Mr. Whatzit: Selections from the 1980s, Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY No Dogs Aloud, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago, IL 2015 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2013 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Derek Eller Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2008 Winsome Works(Some): Career Retrospective, Herron School of Art & Design, Indianapolis, IN Karl Wirsum: Paintings & Prints, Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, Peoria, IL 2007 Winsome Works(Some): Career Retrospective, Chicago Cultural Center, Chicago, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, WI Karl Wirsum: Plays Missed It For You, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2005 Union Art Gallery, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI 2004 Hello Again Boom A Rang: Ten Years of Wirsum Art, Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2002 Paintings and Cutouts, Quincy Art Center, Quincy, IL Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 2001 Rockford College Gallery, Rockford, IL 2000 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL 1998 Jean Albano Gallery, Chicago, IL University Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1997 The University of Iowa Museum of Art, -

50 Years of Chicago Art and Architecture

THE INDEPENDENT VOICE OF THE VISUAL ARTS Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York Volume 33 No. 2 November/December 2018 Established 1973 Gertrude Abercrombie • Ted Argeropoulos • Artists Anonymous (art)n • Mike Baur • Don Baum • Thomas Beeby • Dawoud Bey Larry Booth • Phyllis Bramson • Adam Brooks • Roger Brown Judy Chicago • William Conger • Henry Darger • Ruth Duckworth Jeanne Dunning • Jim Falconer • Virginio Ferrari • Julia Fish • Tony Fitzpatrick • The Five • Jeanne Gang • Theaster Gates • Roland Ginzel Bertrand Goldberg • Leon Golub • Bruce Graham • Art Green • Lee Godie • Neil Goodman • Richard Hunt • Michiko Itatani • Miyoko Ito 50 YEARS OF CHICAGO Helmut Jahn • Gary Justis • Terry Karpowicz • Vera Klement • Ellen Lanyon • Riva Lehrer • Robert Lostutter • Tim Lowly • Kerry James ART AND ARCHITECTURE Marshall • Martyl • Renee McGinnis • Archibald Motley • Walter Netsch • Richard Nickel • Jim Nutt • Sabina Ott • Frank Pannier Ed Paschke • Hirsch Perlman • David Philpot • Martin Puryear Dan Ramirez • Richard Rezac • Suellen Rocca • Ellen Rothenberg Jerry Saltz • Tom Scarff • René Romero Schuler • Diane Simpson Adrian Smith • Nancy Spero • Buzz Spector • Tony Tasset Stanley Tigerman • Gregory Warmack (Mr. Imagination) • Amanda Williams • Karl Wirsum • Joseph Yoakum • Jim Zanzi • Claire Zeisler INSIDE The Hairy Who: The Ones Who Started It All “Art in Chicago”: Artists on the Fracturing 1990s Art Scene A Golden Age in Architecture: 12 Great Building Designs Two Outsider Art Champions: Lisa Stone and Carl Hammer $8 U.S. Two Top Chicago Sculptors Recall Old Times in Chi-Town STATEMENT OF PURPOSE New Art Examiner The New Art Examiner is a publication whose The New Art Examiner is published by the New purpose is to examine the definition and Art Association. -

Via Sapientiae Afterimage

DePaul University Via Sapientiae DePaul Art Museum Publications Academic Affairs 2012 Afterimage Thea Liberty Nichols Dahlia Tulett-Gross Louise Lincoln Jason Foumberg Lucas Bucholtz See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/museum-publications Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Liberty Nichols, Thea; Tulett-Gross, Dahlia; Lincoln, Louise; Foumberg, Jason; Bucholtz, Lucas; DMeo, Mia; Nixon, Erin; Lund, Karsten; Bertrand, Britton; Westin, Monica; Gheith, Jenny; Cochran, Jessica; Ritchie, Abraham; Johnston, Paige K.; Stepter, Anthony; Chodos, Elizabeth; Dwyer, Bryce; Cahill, Zachary; Picard, Caroline; Dluzen, Robin; Kouri, Chad; Isé, Claudine; Satinsky, Abigail; and Farrell, Robyn, "Afterimage" (2012). DePaul Art Museum Publications. 8. https://via.library.depaul.edu/museum-publications/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Affairs at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Art Museum Publications by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Thea Liberty Nichols, Dahlia Tulett-Gross, Louise Lincoln, Jason Foumberg, Lucas Bucholtz, Mia DMeo, Erin Nixon, Karsten Lund, Britton Bertrand, Monica Westin, Jenny Gheith, Jessica Cochran, Abraham Ritchie, Paige K. Johnston, Anthony Stepter, Elizabeth Chodos, Bryce Dwyer, Zachary Cahill, Caroline Picard, Robin Dluzen, Chad Kouri, Claudine Isé, Abigail Satinsky, and Robyn Farrell This book is available at Via Sapientiae: https://via.library.depaul.edu/museum-publications/8 Afterimage 9.14 / 11.18 2012 DePaul Art Museum Carl Baratta / Jason Foumberg David Ingenthron / Jenny Gheith Carmen Price / Caroline Picard Marc Bell / Lucas Bucholtz Eric Lebofsky / Jessica Cochran Ben Seamons / Joel Kuennen Eric Cain / Mia DiMeo David Leggett / Abraham Ritchie Rebecca Shore / Thea Liberty Nichols Lilli Carré / Erin Nixon Amy Lockhart / Paige K. -

Chicago Imagism the Derivation of a Term

The term “Chicago Imagism” has a clear origin, but what is also clear is that the term was not coined to describe that which generally comes to mind when this stylistic de- scription is employed: figurative artists who emerged in Chicago in the mid-1960s, who used vibrant color and depicted the human body grossly distorted, highly stylized, or even schematicized. Needless to say, this has caused confusion in the years since the term came into common use—roughly the early 1970s. Chicago art historian Franz Schulze invented the term, but it was to describe his peer group, artists who emerged in the years after World War II. In his classic book on Chicago art, Fantastic Images, published in 1972, Schulze writes, “The first generation of clear-cut Chicago imagists—nearly all of whom were students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) in the middle and late 1940s—were unqualifiedly op- posed to regionalism, to [Ivan] Albright, and in fact to just about CHICAGO IMAGISM anything else in the history of American art.”1 And the term “imagism” originated, as Schulze explains, in the fact that these artists saw utterly no sense in painting a picture for the picture’s sake, as they associated this with “decorative” artists. In Chicago, Schulze writes, “the image—the face, the figure, often regarded as icon—was considered more psychologically basic, THE DERIVATION more the source of expressive meaning, than any abstract configuration of paint strokes could possibly be.”2 Schulze noted that the New York avant-garde had largely rejected “imagistic art”; it was made “obsolete, so to OF A TERM speak” by the inventions of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. -

Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1936

ANGELS, BIRDS, AND GLOSSARY OF COMMON WINGED MESSENGERS SYMBOLS, THEMES, AND Surrealist art frequently evokes a dreamlike state, emphasizing tran MOTIFS IN SURREALISM sitions between various realities. Angels, birds, and other winged messengers signal movement Death, sleep, dolls, birds, dis between these realities. Birds were torted forms, and myth ology a favorite motif and were used to convey a range of meanings from are just a few of the symbols freedom to peace to power. and motifs in Surrealist art. They conjure complex ideas DEATH The Surrealists were fascinated by and concepts that grew death. The specter of death lingers out of the group’s reactions over works that address mortality, illness, disease, and the memorializ to the devastating loss of life ing of the dead. and significant technological, social, and political changes THE GROTESQUE in post–World War I Europe. The Surrealists challenged ideas of reality. Often they depicted objects The theories of Sigmund or people transformed into absurd or Freud, the Viennese neuro ugly things. These distortions of the logist and father of psycho body often verged on the grotesque. analysis, who looked to MANNEQUINS dreams and the unconscious AND DOLLS Fascinated by automatons, robots, as keys for understanding and other proxies for the human human behavior also body, the Surrealists were part icularly obsessed with mannequins influenced the Surrealists. and dolls. These standins for humans often symbolize the tensions between the animate and inanimate, The following is a key to object and subject, and the real and many recurring themes and the imaginary. symbols that feature in the MYTH AND LEGEND works on view in The Surrealists looked to historical Conjured Life.