Opioid Overdose TOOLKIT: Information for Prescribers TABLE of CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention TOOLKIT

SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention TOOLKIT Opioid Use Disorder Facts Five Essential Steps for First Responders Information for Prescribers Safety Advice for Patients & Family Members Recovering From Opioid Overdose TABLE OF CONTENTS SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit Opioid Use Disorder Facts.................................................................................................................. 1 Scope of the Problem....................................................................................................................... 1 Strategies to Prevent Overdose Deaths.......................................................................................... 2 Resources for Communities............................................................................................................. 4 Five Essential Steps for First Responders ........................................................................................ 5 Step 1: Evaluate for Signs of Opioid Overdose ................................................................................ 5 Step 2: Call 911 for Help .................................................................................................................. 5 Step 3: Administer Naloxone ............................................................................................................ 6 Step 4: Support the Person’s Breathing ........................................................................................... 7 Step 5: Monitor the Person’s Response .......................................................................................... -

Chapter 2 Medication- Assisted Treatment

CHAPTER 2 MEDICATION- ASSISTED TREATMENT Authors: Stephenson, D. (2.1 Methadone) Ling, W.; Shoptaw, S.; Torrington, M. (2.2 Buprenorphine) Saxon, A. (2.3 Naltrexone) 2.1 METHADONE 2.1.1. Introduction to Methadone hours in most patients. Methadone undergoes extensive Treatment first-pass metabolism in the liver. It binds to albumin and other proteins in the lung, kidney, liver and spleen. Tissue stores in these areas build up over time, and there is a Clarification of terms gradual equilibration between tissue stores and methadone in circulation. This buildup of tissue levels produces daily increases in the medication’s impact on the patient until California and Federal Regulations regarding methadone steady state is reached, which takes about 5 days. use the term Opioid Addiction to refer to the condition that is listed in the DSM-5 as Opioid Use Disorder (OUD). Methadone’s unique pharmacologic properties make it highly effective for management of OUD. The slow onset of action Methadone: description, Properties & means that there is no rush after ingestion. The long half-life means that craving diminishes and symptoms of withdrawal Black Box Warning do not emerge between doses, ending the cycling between being sick, intoxicated and normal and decreasing craving. Methadone is a synthetic opioid that can be taken orally and acts as a full agonist at the mu receptor. It is available However, the long half-life also means that any given dose in liquid or tablet form. In California, OTPs are required to of methadone will produce a higher blood level each day use the liquid formulation. -

Alcohol Withdrawal Management Protocols for OASAS 820 Program A

Alcohol Withdrawal Management Protocols for OASAS 820 Program A In order to be eligible for alcohol withdrawal management at OASAS 820 treatment programs, the patient should either be having mild-to-moderate withdrawal (reflected by a CIWA-Ar of at least between 8 and 10) or be expected to have significant withdrawal based upon past medical history, amount and duration of alcohol use, and/or signs of withdrawal beginning while intoxicated/with a detectable blood alcohol content. In addition, the patient should not have acute medical or psychiatric problems that would make care within an OASAS 820 treatment program inadvisable due to safety concerns. As evidence clearly supports the use of benzodiazepines for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal – and chlordiazepoxide appears superior to other benzodiazepines due to its longer half-life and self-tapering effect – this is the preferred drug for alcohol withdrawal management. However, if the patient has a history of liver cirrhosis or is over the age of 60, one may consider the use of lorazepam as it is mostly metabolized via Phase 2 conjugation as opposed to Phase 1 oxidation and may be a safer choice in specific situations. The choice of alcohol withdrawal management protocols is a complex one, governed by the premise that the goal is to perform the safest and most comfortable withdrawal management possible. Both undermedication and overmedication are problematic. If a patient is undermedicated, particularly for alcohol withdrawal, one risks the possibility that the patient may progress to severe withdrawal and delirium tremens (which carries a mortality rate of about 5%). On the other hand, overmedication can lead to over-sedation, which can result in dangerous behavior as well as falls and other traumatic injuries. -

TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder For Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families TREATMENT IMPROVEMENT PROTOCOL TIP 63 Please share your thoughts about this publication by completing a brief online survey at: https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/KAPPFS The survey takes about 7 minutes to complete and is anonymous. Your feedback will help SAMHSA develop future products. TIP 63 MEDICATIONS FOR OPIOID USE DISORDER Treatment Improvement Protocol 63 For Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families This TIP reviews three Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for opioid use disorder treatment—methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine—and the other strategies and services needed to support people in recovery. TIP Navigation Executive Summary For healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families Part 1: Introduction to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Treatment For healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families Part 2: Addressing Opioid Use Disorder in General Medical Settings For healthcare professionals Part 3: Pharmacotherapy for Opioid Use Disorder For healthcare professionals Part 4: Partnering Addiction Treatment Counselors With Clients and Healthcare Professionals For healthcare and addiction professionals Part 5: Resources Related to Medications for Opioid Use Disorder For healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families TIP 63 MEDICATIONS FOR OPIOID USE DISORDER Contents EXECUTIVE -

Psychiatric Medications in Children ‐ 101

Psychiatric Medications in Children ‐ 101 Cindy Ellis, M.D. Developmental/Behavioral Pediatrics June 26, 2015 OBJECTIVES • Discuss general principles regarding use of psychotropic medications • Review how medications work in the body and considerations for use in children • Overview of specific medications and indications for use in the pediatric population Treatments for Emotional and Behavioral Problems Educational • Information Behavioral • Address functions • External modifications Biomedical • Target underlying neurological functioning Biomedical Treatments Focus on the potential links between: Symptoms of the disorder (expressed in behavior) and Neurobiologic systems involved in the etiology and pathogenesis of the symptoms (e.g., specific neurotransmitter systems) Pharmacological or medication treatments Most widely used biomedical treatment for behavioral and emotional problems in children Biomedical Treatment: Medication Typically considered when problem or symptoms of the disorder: – Significantly interfere with an individual’s functioning – Have not responded or shown suboptimal response to appropriate behavioral interventions, or – Pose an acute safety risk How Medications Work in the Body • Most drugs alter central nervous system function by acting at the level of the individual nerve cell • The human brain contains approximately 20 billion neurons • Groups of neurons in the brain have specific functions • some are involved with thinking, learning, and memory • some are responsible for receiving sensory information. • some communicate with muscles, stimulating them into action How Medications Work in the Body Each neuron has a cell body, an axon, and many dendrites • The cell body controls all of the cell's activities • The axon extends out from the cell body and transmits messages to other neurons • Dendrites also branch out from the cell body. -

![[T]His Advertising Promotes Only the Most Expensive](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3287/t-his-advertising-promotes-only-the-most-expensive-2733287.webp)

[T]His Advertising Promotes Only the Most Expensive

presents "[T]his advertising promotes only the most expensive products, it drives prescription costs up and also encourages the 'medicalization' of American life — the sense that pills are needed for most everyday problems that people notice, and many that they don’t." — Jerry Avorn, New York Times Convincing people they are sick and need a drug is a multi-billion dollar industry. In 2015, Big Pharma dropped a record- breaking $5.4 billion on direct-to-consumer (DTC) ads, according to Kantar Media. And it paid off for Big Pharma. The same year, Americans spent a record $457 billion on prescription drugs. The U.S. and New Zealand are the only countries where DTC is legal. Americans also pay more for drugs and devices than any other country. The bulk of these ads appear on TV at a rate of 80 ads per hour of programming, according to Nielsen. Behind the drug and device ads saturating TV, radio and digital media are hidden costs and devastating side effects that companies don't advertise, and critics say the ads drive up drug prices and erode the patient-doctor relationship. With the price of drugs skyrocketing, politicians and health-care providers question Pharma's DTC spending, which exceeds money spent on research and development. Even presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton called for an end to tax breaks for drug ads and for tougher regulations. But the money spent on DTC is just one small cog in Big Pharma's well-oiled marketing machine. Companies spend billions more on getting doctors to write prescriptions for their expensive brand-name drugs or devices for uses not approved by the Food and Drug Administration — a controversial practice called off-label marketing. -

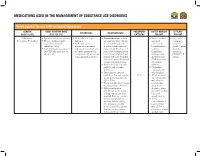

Medications Used in the Management of Substance Use Disorders

MEDICATIONS USED IN THE MANAGEMENT OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) for Opioid Dependence GENERIC ADULT STARTING DOSE PREGNANCY SAFETY MARGIN EFFICACY ADVANTAGES DISADVANTAGES (BRAND NAME) (MAX PER DAY) CATEGORY FOR OAT FOR OAT Methadone • Specialty consultation advised. • Give orally in a single • Contraindications include • Serious overdose • First-line (Dolophine, Methadose) • Titrate carefully, consider daily dose. any situation where Opioids and death treatment methadone’s delayed • FDA approved for are contraindicated, such may occur if option for cumulative effects. detoxification treatment as patients with respiratory benzodiazepines, chronic Opioid • Individualize dosing regimens and maintenance treatment depression (in the absence of sedatives, dependence (AVOID same fixed dose for of Opioid dependence in resuscitative equipment or in tranquilizers, that meets all patients). conjunction with appropriate unmonitored situations) and antidepressants, DSM-IV-TR social and medical services. patients with acute bronchial alcohol or other criteria. asthma or hypercarbia, known CNS depressants or suspected paralytic ileus. are taken in • May prolong QTc intervals addition. on ECG; risk of cardiac • Methadone arrhythmias. contraindicated • Discontinue or taper the with selegiline. methadone dose and consider C/D • Avoid concurrent an alternative therapy if the use of methadone QTc > 500ms. with nilotinib, • Plasma half-life may be longer tetrabenazine, than the analgesic duration. ziprasidone, • Delayed analgesia or alcohol, st. johns toxicity may occur because wort, valerian, kava of drug accumulation after kava, and repeated doses, e.g., on days grapefruit juice. two to five; if patient has • Avoid excessive sedation during concurrent use of this timeframe, consider buprenorphine temporarily holding dose(s), with alcohol, st. lowering the dose, and/or johns wort, valerian slowing the titration rate. -

A Guide to Substance Abuse Services for Primary Care Clinicians

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment A Guide to Substance Abuse Services for Primary Care Clinicians Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 24 A Guide to Substance Abuse Services for Primary Care Clinicians Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 24 Eleanor Sullivan, Ph.D., R.N., F.A.A.N. Michael Fleming, M.D., M.P.H. Consensus Panel Co-Chairs U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 1 Choke Cherry Road Rockville, MD 20857 This publication is part of the Substance Abuse I.C.A.D.C., served as the CSAT government Prevention and Treatment Block Grant technical project officer. Paddy Cook, Constance Grant assistance program. All material appearing in Gartner, M.S.W., Lise Markl, Randi Henderson, this volume except that taken directly from Margaret K. Brooks, Esq., Donald Wesson, M.D., copyrighted sources is in the public domain and Mary Lou Dogoloff, Virginia Vitzthum, and may be reproduced or copied without Elizabeth Hayes served as writers. Special permission from the Substance Abuse and thanks to Daniel Vinson, M.D., M.S.H.P., Mim J. Mental Health Services Administration’s Landry, Mary Smolenski, C.R.N.P., Ed.D., (SAMHSA) Center for Substance Abuse MaryLou Leonard, Pamela Nicholson, Annie Treatment (CSAT) or the authors. Citation of Thornton, Jack Rhode, Cecil Gross, Niyati the source is appreciated. Do not reproduce or Pandya, and Wendy Carter for their distribute this publication for a fee without considerable contributions to this document. -

Reasons Behind Teachers' Participation in the Medicalization Of

Title Caring, control, and accountability: Reasons behind teachers’ participation in the medicalization of ADHD-related behaviors Abstract Schools collaborate with the public health institutions, and teachers are mandated to screen for potential mental problems in their students. The case of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) puts that role in evidence. Our main objective is to explore the reasons underlying teachers’ actions regarding the medicalization of ADHD-behaviors in elementary school children. The results showed that teachers participate in a great variety of actions before, during and after the clinical evaluation for ADHD. Teacher willingness to contribute to the medicalization process results from teachers a) caring about their students and wishing to improve their well-being; b) seeking to control students’ behaviors and their consequences, and c) feeling accountable for their teacher’s role as disorder spotter and their students’ success. (text 1844 words) Introduction Schools in Western contexts have a long history of collaboration with the public health institutions (Cohen, 1983; Petrina, 2006). In addition to health care professionals working within the school (psychologists, doctors, nurses, etc.), teachers are mandated to screen for potential mental, behavioral and academic problems in their students (Singh, 2006; Cohen, 1983; Petrina, 2006). The case of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) puts that role of teachers in evidence. ADHD is a psychiatric diagnosis fully described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual and is referred to as the most prevalent mental disorder in youth. It is nevertheless at the heart of many controversies, because its main symptoms, namely inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, are all very common behaviors in children, which increases the difficulty to draw a clear-cut line between normalcy and pathology and makes more apparent the subjectivity of the diagnosis process (Conrad, 2006). -

Surdiagnostic-Plan-Action-En (Abs57)

SYMPOSIUM QUÉBÉCOIS SUR LE SURDIAGNOSTIC OVERDIAGNOSIS: FINDINGS AND ACTION PLAN OVERDIAGNOSIS: FINDINGS AND ACTION PLAN | A But the 1 percent of patients who consume some 21 percent of health care costs, usually succumbing gradually from multi-organ failure, illustrate the progress problem. Fifty years ago they would have died faster and, in many cases, with less suffering. We have traded off shorter lives and faster deaths for just the opposite, longer lives and slower death.” — DANIEL CALLAHAN The Difficult Child of Medical Progress, 2012 Table of contents Glossary . 1 Introduction . 3 A Definition and the Theoretical Model . 4 Key Elements of the Symposium . 7 What You Told Us . 9 “Patients” Vector . 9 “Health Care Providers” Vector . 12 “Culture” Vector . 14 “System” Vector . 15 6. Action Plan . 17 Orientation 1 . 17 Orientation 2 . 18 Orientation 3 . 19 Orientation 4 . 19 Orientation 5 . 20 Orientation 6 . 21 Orientation 7 . 22 7. Conclusion . 23 Glossary ACMDP: Québec Association of Councils of INSPQ: National Institute of Public Health Physicians, Dentists and Pharmacists The mission of the Institute is to provide support to the ACMDP is the association of Councils of physicians, dentists Minister of Health and Social Services and to the regional and pharmacists (CMDPs) of the province. In each of the authorities in connection with their responsibilities in the field health care facilities, the CMDP has the responsibility to of public health. More specifically, the mission of the Institute control the quality of medical procedures. It formulates involves contributing to the development, consolidation, recommendations, evaluates the skills of physicians, dentists dissemination and application of knowledge in the field of and pharmacists, and gives advices on professional aspects public health. -

Towards a Rhizomatic Perspective of the Medicalized Body?

methaodos.revista de ciencias sociales, 2019, 7 (2): 184-197 Adriane Roso ISSN: 2340-8413 | http://dx.doi.org/10.17502/m.rcs.v7i2.302 Towards a rhizomatic perspective of the medicalized Body? A Review on Medicalization and Gender ¿Hacia una perspectiva rizomática del cuerpo medicalizado? Una revisión sobre la medicalización y el género Adriane Roso https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7471-133X Universidad de Harvard, Estados Unidos. [email protected] Recibido: 15-05-2019 Aceptado: 30-07-2019 Abstract Medicalization has been one of the most important topics for feminist agenda and gender studies. During the second wave of feminism, when sexual and reproductive rights were the top concerns for women, is exactly when the studies of medicalization started to grow. The goal of this research is to present some characteristics of the studies that are concerned with the gendered medicalized body by indicating how the medicalization process has been explained, understood and interlaced with different institutions and people. One main concern in this review is to pay attention to how gender is expressed in medicalization studies. Within a qualitative design, and the support of SPSS™, we constructed a mapping review on the literature published in books, and thereafter we developed a content analysis of the chapters on medicalization. An overview of the characteristics of the studies are presented, and after two categories are discussed: (a) meanings of medicalization and (b) medicalizing bodies and its entrepreneurs: a rhizomatic expression. It was concluded the medicalization thesis should be considered as one line of a “rhizome” that connects to different actors, corporations and organizations. -

Perceived Trends in ADHD Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment in Vermont Schools

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses Undergraduate Theses 2015 Perceived Trends in ADHD Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment in Vermont Schools Charlotte F. Wonnell University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses Recommended Citation Wonnell, Charlotte F., "Perceived Trends in ADHD Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment in Vermont Schools" (2015). UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses. 2. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses/2 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Perceived Trends in ADHD Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment in Vermont Schools Charlotte Wonnell [email protected] 4/17/15 College Honors Thesis B.A. Degree in Anthropology and Psychology at the University of Vermont Committee Members: Dr. Jeanne Shea (Advisor), Dr. Judith Christensen (Chair), Dr. Alessandra Rellini 1 Abstract: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) has become a topic of popular discussion over the past couple decades because of its steady increase in prevalence among children and the concomitant increase in need for medication and services, with much debate centered on the reasons for this increase (Carpenter-Song, 2009). Although a hot social topic, research to date has not yet come to a definitive consensus. By exploring school staff views of and approaches to ADHD in Vermont schools, my thesis describes perceived trends in ADHD symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment from the local, front-line perspective of a sample of Vermont school staff.