Eating up Tradition: an Autoethnographic Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 26, 2019

d's Dairy orl In W du e st h r t y g W n i e e v Since 1876 k r e l y S NEW 2-PIECE DESIGN CHEESE REPORTER Precise shreds with Urschel Vol. 144, No. 6 • Friday, July 26, 2019 • Madison, Wisconsin USDA Details Product Purchases, US Milk Production Rose 0.1% In June; Other Aspects Of Farmer Trade Aid Second-Quarter USDA’s Ag Marketing vice (FNS) to food banks, schools, a vendor for distribution to indus- Output Down 0.1% Service To Buy $68 Million and other outlets serving low- try groups and interested parties. Washington—US milk produc- income individuals. Also, AMS will continue to tion in the 24 reporting states In Dairy Products, Starting AMS is planning to purchase an host a series of webinars describ- during June totaled 17.35 billion After Oct. 1, 2019 estimated $68 million in milk and ing the steps required to become pounds, up 0.1 percent from June Washington—US Secretary of other dairy products through the a vendor. 2018, USDA’s National Agricul- Agriculture Sonny Perdue on FPDP. Stakeholders will have the tural Statistics Service (NASS) Thursday announced details of the AMS will buy affected products opportunity to submit questions to reported Monday. $16 billion trade aid package aimed in four phases, starting after Oct. be answered during the webinar. The May milk production esti- at supporting US dairy and other 1, 2019, with deliveries beginning The products discussed in the mate was revised upward by 18 agricultural producers in response in January 2020. -

Meat and Muscle Biology™ Introduction

Published June 7, 2018 Meat and Muscle Biology™ Meat Science Lexicon* Dennis L. Seman1, Dustin D. Boler2, C. Chad Carr3, Michael E. Dikeman4, Casey M. Owens5, Jimmy T. Keeton6, T. Dean Pringle7, Jeffrey J. Sindelar1, Dale R. Woerner8, Amilton S. de Mello9 and Thomas H. Powell10 1University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA 2University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA 3University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA 4Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA 5University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA 6Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 7University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA 8Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA 9University of Nevada, Reno, NV, 89557, USA 10American Meat Science Association, Champaign, IL 61820, USA *Inquiries should be sent to: [email protected] Abstract: The American Meat Science Association (AMSA) became aware of the need to develop a Meat Science Lexi- con for the standardization of various terms used in meat sciences that have been adopted by researchers in allied fields, culinary arts, journalists, health professionals, nutritionists, regulatory authorities, and consumers. Two primary catego- ries of terms were considered. The first regarding definitions of meat including related terms, e.g., “red” and “white” meat. The second regarding terms describing the processing of meat. In general, meat is defined as skeletal muscle and associated tissues derived from mammals as well as avian and aquatic species. The associated terms, especially “red” and “white” meat have been a continual source of confusion to classify meats for dietary recommendations, communicate nutrition policy, and provide medical advice, but were originally not intended for those purposes. -

Char Siu Pork

Char siu pork This is a popular Chinese barbecue dish, also common in Vietnam, where it’s called thịt xá xíu. It is absolutely delicious with rice and salad, in bánh mì (Vietnamese baguette sandwiches), in steamed buns or just on its own as soon as you’ve sliced it. This recipe is thanks to Andrea Nguyen, author of ‘Into the Vietnamese Kitchen: Treasured Foodways, Modern Flavors’. Serves: 4-6 1kg pork shoulder, in one piece 2 cloves garlic, minced 2 tbsps sugar ½ tsp Chinese five-spice powder 3 tbsps hoisin sauce 2 tbsps Shaoxing rice wine or dry sherry 2 tbsps light soy sauce 1 tbsp dark soy sauce 2 tsps sesame oil 1. Trim any large swathes of fat off the pork. Cut it into several fat strips – each approx 6-8” x 1½” x 1½”. 2. Whisk remaining ingredients together to make marinade. Add meat, turn to coat, cover and leave in fridge overnight or for at least 6 hours. Turn occasionally. 3. Remove meat from fridge one hour before cooking. Heat oven to 250C, with a rack positioned in the upper third. Line a roasting tin with foil and position a roasting rack on top. Place meat on rack, spaced well apart. Reserve marinade. 4. Place tin in oven and roast for 35 mins. Every 10 mins remove roasting tin from oven and, using tongs, dredge each piece of meat in the reserved marinade and return to the rack, turned over. After 35 mins the meat should be beginning to char in places and should read 60-63C on a meat thermometer inserted into the thickest part. -

Menu for Week

Featured Schinkenspeck (Berkshire - Mangalitsa) $9.50 per 4 oz. pack A proscuitto-like dry-cured dry-aged ham from Southern Germany. Well-marbled Berkshire – Mangalitsa sirloins are dry-cured for weeks and then hung to dry-age for months. Use like proscuitto. Sliced extra fine with about 10-12 slices per pack. Smoked Lardo Butter (Idaho Pasture Pork) $10 per đ lb. container Dry-aged Italian lardo from local acorn and walnut-finished Idaho Pasture Pigs is briefly smoked over rosemary sprigs and then minced and slowly rendered before being blended with roasted garlic, white wine, leaf lard and butter. Use for pan sauces, sautéing or just spread on bread. Smoked Kippered Wagyu Beef LIMITED $15 per lb. for unsliced pieces Better, softer version of jerky. Wagyu beef lifter steaks dry-cured and glazed with molasses, chilis, garlic and more. Hot smoked over oak and mulberry. Slice thinly and serve. 21-Day Aged Prime+ Top Sirloin Steaks (BMS Grade 8+ Equivalent) $19.95 per lb. A whole top sirloin dryaged for 21 days. Extra tender, beefy and the perfect amount of “aged funk”. Braunschweiger (Duroc and Berkshire) $10 per lb. (unsliced) Traditional braunschweiger with pork liver and a nice smoky flavor from being 33% dry-cured bacon ends. BACONS Beef Bacon (Piedmontese beef) $9 per lb. (sliced) Grass-fed local Piedmontese beef belly dry- cured 10 days, coated with black pepper & smoked over apple. Country Bacon (Duroc) $9 per lb. (sliced) Traditional dry-cured bacon smoked over a real wood fire of oak and mulberry. Traditional Bacon (Duroc) $9 per lb. -

Home Sausage Making Second Edition

HOME SAUSAGE MAKING SECOND EDITION ���������� �� ������ ������� HOME SAUSAGE MAKING SECOND EDITION By I. J. Ehr, T. L. Tronsky D.R. Rice, D. M. Kinsman C. Faustman Department of Animal Science University of Connecticut Storrs, Connecticut 06268 Table of Contents Introduction-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Equipment---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Sanitation----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Ingredients, Additives, and Spices------------------------------------------------------------------------ 5 Spice Chart--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 General Conversions---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Casings-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Game Meat-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 Recipes------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 Fresh Sausages Fresh Pork Breakfast ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 Fresh Italian---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10 Cooked Sausages Bratwurst------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Breakfast Favorites Hotcakes & French Toast Side Orders Pastries Eggs & Omelettes Daily Breakfast Specials Served As

Daily Breakfast Specials Served as stated 4.99 Hotcakes & French Toast MONDAY: Two Eggs with Toast 1 Hotcake with Syrup ..........................................................3.99 3 pc. Mush with Beef or Tomato Gravy TUESDAY: 2 Hotcakes with Syrup .......................................................5.99 WEDNESDAY: 2 pc. French Toast with 2 pc. Bacon or 1 Sausage Patty Belgian Waffle with Syrup ..................................................5.99 THURSDAY: Sm Order Biscuits, Home Fries, & Sausage Gravy French Toast with Syrup (3 slices) ........................................5.99 FRIDAY: 1 Hotcake with 2 pc. Bacon or 1 Sausage Patty Apple Cinnamon French Toast with Syrup ......................6.99 Stuffed French Toast with Fruit Topping .........................7.29 Eggs & Omelettes Egg Beaters available for +1.99 Prayer: Comes with choice of toast, mini hotcakes, biscuit, bagel, or muffin. Lord, thank You for the family and friends beside us, Pastries the love between us, and the food before us. Amen. 1 Egg ......................................................................................4.49 Donut .................................................................................... 1.79 2.99 2 Eggs ....................................................................................5.49 Breakfast Favorites Cinnamon Roll ..................................................................... Pecan Roll ............................................................................. 3.49 Cheese Omelette .................................................................7.29 -

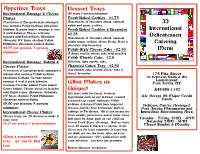

Catering Menu

Appetizer Trays Dessert Trays International Sausage & Cheese All trays 5 person minimum Platter Fresh-Baked Cookies - $1.75 A selection of European-style sausages Assortment of chocolate chunk, oatmeal JJ that includes Polish kielbasa, Ukrainian raisin and sugar cookies. kielbasa, German hunter sausage & veal Fresh-Baked Cookies & Brownies International & pork kabanos. Cheese selection $2.25 Delicatessen includes mild Dutch Edam, Ukrainian Assortment of chocolate chunk, oatmeal Abbatsky, NY State cheddar, Polish raisin, sugar cookies, chewy Rocky Road & Catering Holldamer, Ukrainian smoked Swiss. chocolate chip brownies. $4.75 per person, 5 person Polish-Style Cheese Cake - $2.50 Menu minimum A dense ricotta cheese cake with peaches Polish Marble Cake - $2.5 International Sausage, Salami & Delicious, light marble cake Cheese Platter Assorted Cakes Tray - $2.50 A selection of European-style sausages & Our marble cake, ricotta cheese cake & salamis that includes Polish kielbasa, chewy brownies 174 Pike Street Ukrainian kielbasa, German hunter (in between Dad’s & the sausage & veal & pork kabanos, What Makes us Laundromat) German Cerevlat salami, Paris salami, Port Jervis, NY Genoa salami. Cheese selection includes Unique? (845)858-1142 mild Dutch Edam, Ukrainian, Abbatsky, We start with the finest, freshest NY State cheddar, Polish Holldamer, ingredients such as our in-house roasted, We Accept All Major Credit Ukrainian smoked Swiss. seasoned top round, authentic Polish Cards $5.00 per person, 5 person kielbasa, delicious Polish ham, imported Delivery Can be Arranged, minimum cheeses and the best homemade stuffed Port Jervis, Matamoras and International Cheese Platter cabbage in Tri-States. All of our meats are Immediate Surrounding Area Choose from our 28 cheeses to make it from smaller processors and in some cases still made by hand, such as our delicious Tuesday – Friday, 9AM – 6PM your own! Saturday 9AM – 5PM $4.25 per person, 5 person minimum Forest Pork Store offerings. -

Product Catalog MIKE HUDSON DISTRIBUTING

2021 Product Catalog MIKE HUDSON DISTRIBUTING Retail Cheese - Dairy Protein Grocery Food Service Cheese - Dairy Protein Deli-Bakery Pizza Non-Food Cleaners Supplies Packaging 1 Welcome to 2021! As we turn the calendar to a new year, we are encouraged by the ongoing fortitude displayed by our customer and manufacturing partners. We have a long way to go to “get back to normal,” but rest assured that whatever challenges we face in the future, we will meet them together and come out of this more vital than ever. Mike Hudson Distributing is committed to providing quality products, timely deliveries, and competitive pricing to all our customers. With a sales territory from San Jose along Highway 101 to the Oregon border and from the California coastline to the Central Valley, we live up to our promise of delivering quality products and outstanding service to the independent operator. Our ability to accomplish this is due primarily to the longstanding relationships and support of our supplier partners. We proudly market and distribute products from some of the most trusted names in the foodservice industry as well as from local suppliers that you have grown to recognize for their uniqueness and quality. All of which can be found in this Product Catalog. We recommend taking a few minutes to browse our Product Catalog of all products we carry - national brands, locally sourced offerings, and an extensive specialty cheese selection. As we add to our product offering throughout the year, our Marketing and Sales Teams will provide you with new product announcements and details. Even more, than in years past, we are thankful for our relationships throughout the foodservice industry. -

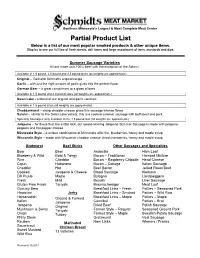

Partial Product List

Southern Minnesota’s Largest & Most Complete Meat Center Partial Product List Below is a list of our most popular smoked products & other unique items. Stop by to see our full line of fresh meats, deli items and large assortment of jams, mustards and dips. Summer Sausage Varieties All are made with 100% beef with the exception of the Salami. Available in 1.5 pound, 2.0 pound and 2.5 pound sizes (all weights are approximate) Original – Gerhardt Schmidt’s original recipe Garlic – with just the right amount of garlic gives this the perfect flavor German Beer – a great compliment to a glass of beer Available in 1.5 pound and 2.0 pound sizes (all weights are approximate) Swan Lake - a blend of our original and garlic varieties Available in 1.5 pound sizes (all weights are approximate) Cheddarwurst – sharp cheddar cheese gives this sausage intense flavor Salami – similar to the Swan Lake variety, this is a cooked summer sausage with both beef and pork. Specialty Sausages: only available in the 1.5 pound size (all weights are approximate) Jalapeno – for those that like a little kick, our award-winning Jalapeno Summer Sausage is made with jalapeno peppers and hot pepper cheese Minnesota Style – a unique combination of Minnesota wild rice, blueberries, honey and maple syrup Wisconsin Style – made with Wisconsin cheddar cheese, dried cranberries, honey and maple syrup Bratwurst Beef Sticks Other Sausages and Specialties Beer Beer Andouille Ham Loaf Blueberry & Wild Bold & Tangy Bacon – Traditional Hamball Mixture Rice Cheddar Bacon – Raspberry -

Ashland Sausage Company

=================================================================== ashland sausage company =================================================================== OUR HISTORY In 1960, when Stanley Podgorski visited she joined forces with her parents in 2001. to grow, we will carry on our tradition to America with his father, he saw that hard Their son, Paul, has also expressed an provide the uncompromising quality our work, determination and sometimes a little interest in the business and plans on joining customers have grown to expect. luck could get you somewhere in life. He the rest of the family when he completes had a dream to return one day and be his B.A., also in business management. Ashland Sausage Company is a family owned successful. He arrived in 1971 with his wife Their oldest daughter, Beata, has joined the business in its 2nd generation, devoted Theresa, and they opened a small grocery company as well this past to delivering delicious, high quality meat store on Chicago’s south side. Their customer year making this a true “family business.” products. We manufacture all our products base caused them to quickly outgrow that using traditional ingredients and methods. small store and they opened a larger one We have kept everything focused on the We try to stick to the way sausages were on the north side, where they continued to consumer from our inception. Our goal is amde decades ago, using many of the age smoke sausages in their back smokehouse. to convey our idea of excellence, quality, old European sausage-making techniques. In 1986, the opportunity arose to purchase and tradition to our customers. Our family Our Midwest location insures the best a large manufacturing facility on Division prides itself on the fact that we do things sources of fresh beef and pork, the basic Street, named Ashland Sausage Company. -

DONALD LINK Herbsaint and Cochon Restaurants – New Orleans, LA

DONALD LINK Herbsaint and Cochon Restaurants – New Orleans, LA * * * Date: March 21, 2007 Location: Herbsaint – New Orleans, LA Interviewer: Amy Evans Length: 1 hour, 2 minutes, 41 seconds Project: Southern Boudin Trail & Southern Gumbo Trail © Southern Foodways Alliance www.southernfoodways.com 2 [Begin Donald Link] 00:00:00 Amy Evans: This is Amy Evans on Wednesday, March 21, 2007 for the Southern Foodways Alliance in New Orleans, Louisiana, at Herbsaint with Chef Donald Link. And Donald, if you wouldn’t mind saying your name and also your birth date for the record. 00:00:14 Donald Link: Donald Link. Birthday July 18, 1969. [Phone Rings] 00:00:20 AE: Okay. And we have a lot to talk about here today, but we’re here to talk first about boudin and then a little bit about gumbo. But first I want to kind of couch our discussion in some history of your family and—and your—your Cajun background. 00:00:34 DL: My family is—my last name is Link, obviously, and my dad—that’s my dad’s last name, and his mom’s last name is Zaunbrecher [pronouncing this Zon-brecker]. It depends on where you come from; over there they call it Zaunbrecher [Zon-breaker]; in Germany it’s Zaunbrecher [Soun-bre-sha]. And they came from Germany in 1880 with a group of forty immigrants. Forty families came over, and they settled in Robert’s Cove, Louisiana, which is practically, I guess, in Rayne, and that’s a community there. And then from—that stretches from where I-10 first comes off in Rayne [Louisiana], coming from New Orleans all the way through Basile [Louisiana], I think. -

Platters & Baskets Trifold 2016

¢ ¢ Gifts Maxwell’s Market is a local, family Gift certificates are available in any amount. Gifts owned market. We pride ourselves on MAXWELL’S described below are gift wrapped in a rustic crate. All prices are subject to change. our customer service. When shopping with us, you will find a friendly, well STEAK DINNER informed staff to make Includes: Two hand cut steaks, two twice baked recommendations, answer questions, MARKET potatoes, fresh French bread, one of our homemade and prepare your order to your dips, crackers, and two cookies. specifications. Looking for something Choose filet mignon or ribeye steaks. special? We can special order almost Market Price. Let us add a bottle of wine for $15 anything. Just ask! Maxwell’s provides a superior shopping WINE & CHEESE experience. We offer a wide selection of Let us choose a bottle of wine to compliment two cheeses, fruit, crackers, and cheese straws. Starting fresh meats and seafood as well as at $45. prepared foods, ready for the grill or Party Trays oven. Browse our myriad imported and SHISH-KABOB DINNER domestic beers and wines. In the pantry Includes: Two beef, chicken, or shrimp kabobs, two you'll find those difficult to find specialty twice baked potatoes, two vegetable kabobs, one of items and gourmet foods. our homemade dips, crackers and two cookies. Dinner for 2 people $55. GIFTS Additional serving $15.00. Pastries A dozen assorted cookies and six fudge nut MARKET HOURS brownies, garnished with strawberries. Starting at $45. MONDAY - SATURDAY 10 AM - 7 PM STEAK BOX Six 8 oz. filets or six 12 oz.