Retrofitting Suburbia | P a G E 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BICYCLES Are Unequalled in CONNECTION WE HAVE a FIRST-CLASS CYCLE in the City

•y.'/ VW///J-iw <f>-_^^?-"- W^S^^^^^S^^^i-^. A JOURNAL OF CY©L-lk9 LITERATURE TRADE i&gWS. b VOL. V. MILWAUKEE, Wis., APRIL, 1894. >v'if8%'v v NO. 1. YcYevs ©cordis AVc invito iiispi-'ution of our lino. Catalogues fpno al lluniblor Agimdes. GORMULLY & JEFFERY MFG. CO. (..'MICA (JO. BOSTON. WASHINGTON. NKW YfMK. COVKNTUY, KNllLANI). JOHN MEUNIER GUN CO., AGENTS FOR MILWAUKEE, 272 WEST WATER STREET. MENTION THE "PNSUS." THE PNEUMATIC. H. L. KASTEN & CO. STEARNS 517 GRAND AVE. MILWAUKEE E Don't Take A. Our Word s R For It N Come S and See E ..*••' the Wheel H. L. KASTEN & CO. 517 GRAND AVE. M MILWAUKEE STEARNS MENTION THE PNEUS" IN CONNECTION WITH OUR Reitzner - WicKs Gucie Go. =TYPEWRITER=BUSINESS Successors to REITZNER-PRICHARD CYCLE CO. WE HAVE SECURED THE AGENCY FOR THE WELL-KNOWN AND ... MANUFACTURERS OF... MERCURY ....CELEBRATED.... FOWLER FLIERS WHEELS AND AGENTS FOR-, The Celebrated HARRY JAMES CYCLES. A COMPLETE LINE OF THESE MACHINES CAN BE SEEN The CLEVELAND and SMALLEY Wheels. AT OUR STORE 414 Broadway = Milwaukee, LOOK TO YOUR WHEELS WHEELS FITTED WITH MORGAN & WRIGHT, PALMER AND Q..&, J, TIRES. WOOD OR STEEL RIMS, Our Facilities for REPAIRING BICYCLES are Unequalled IN CONNECTION WE HAVE A FIRST-CLASS CYCLE in the City. REPAIR SHOP. 444 National Ave., Milwaukee. Badoer Typewriter * Stationery Go. MENTION THE "PNEUS. MENTION THE "pNEUS.' E. D. HAVEN, Manager. THE PNEUMATIC. -Photographic-Supplies- FOR SALE FOR AMATEURS. A BARGAIN JOHN B. BANGS & 60. 375 MILWAUKEE STREET Brand new ARROW Safety Aoaiomy of Mooio Bulldlnjj, KODAKS REFILLED, Bicycle, same as was sold all last DEVELOPING AND PRINTING. -

Safe Speed for All Road Users: Promoting Safe Walking and Cycling

Safe Speed: promoting safe walking and cycling by reducing traffic speed This report has been prepared by Dr Jan Garrard for the Safe Speed Interest Group, November, 2008. © 2008 Safe Speed Interest Group, comprising the Heart Foundation, City of Port Phillip and City of Yarra Cover images: © City of Port Phillip Material documented in this publication may be reproduced providing due acknowledgement is made. Enquiries about this publication should be addressed to the Secretariat of the SSIG: Heart Foundation Level 12, 500 Collins St Melbourne, Victoria 3000 Phone: (03) 9329 8511 2 Safe Speed: promoting safe walking and cycling by reducing traffic speed Contents Executive summary 4 Full report 12 1. Introduction 12 2. Active transport in Australia 15 3. Speed and active transport 17 4. Evidence associated with reduced vehicle speed and active travel 18 4.1 Vehicle speed and active travel behaviour 18 4.2 Vehicle speed and perceptions of pedestrian/cyclist safety and community amenity 27 4.3 Vehicle speed and injury to pedestrians and cyclists 30 4.4 Perceived and actual safety, and active transport 38 5. Implementation issues 39 5.1 Area‐wide versus site‐specific traffic calming 39 5.2 Speed reduction and the Safe System approach to road safety 40 5.3 Barriers to speed reduction: perceived and actual impacts on travel time 41 5.4 Community attitudes to speed reduction 42 5.5 Health and environmental benefits of lower speed limits 44 5.6 Lessons from overseas 45 6. Conclusions 46 References 50 Appendices 59 Appendix A: Summary of the health benefits of active transport 59 Appendix B: ‘Sharp rise in deaths of elderly pedestrians’‐ The Age, 7th Sept 2008 65 Appendix C : Summary of: ‘Speed management: a road safety manual‐ WHO 2008 66 3 Safe Speed: promoting safe walking and cycling by reducing traffic speed Executive summary 1. -

UNIFIED WORK PROGRAM (UWP) for NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS Quarterly Progress Report- FY 2011 1St Quarter

UNIFIED WORK PROGRAM (UWP) FOR NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS Quarterly Progress Report- FY 2011 1st Quarter UNIFIED WORK PROGRAM (UWP) FOR NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS Quarterly Progress Report- FY 2011 1st Quarter TABLE OF CONTENTS (BY RECIPIENT AGENCY) CMAP................................................................................................................................... 2 City of Chicago................................................................................................................... 56 CTA....................................................................................................................................... 75 Regional Council of Mayors............................................................................................ 94 Lake County........................................................................................................................ 98 McHenry County................................................................................................................ 105 Metra..................................................................................................................................... 108 Pace........................................................................................................................................ 117 RTA........................................................................................................................................ 132 West Central Municipal Conference............................................................................. -

Sport and Recreation Strategy Background Report

SPORT AND RECREATION STRATEGY BACKGROUND REPORT ‘Getting Our Community APagective’ 1 of 166 About this document The City of Port Phillip’s Sport and Recreation Strategy 2015-24 provides a framework which achieves our objective of developing a shared vision for Council and the community, to guide the provision of facilities and services to meet the needs of the Port Phillip community over the next ten years. The documents prepared for this strategy are: Volume 1. Sport and Recreation Strategy 2015-24 This document outlines the key strategic directions that the organisation will work towards to guide the current and future provision of facilities and services to meet the needs of the Port Phillip community over the next ten years. Volume 2. Getting Our Community Active – Sport and Recreation Strategy 2015-24: Implementation Plan This document details the Actions and Tasks and the associated Key Performance Indicators KPI’s required to achieve Council’s defined Goals and Outcomes. Volume 3. Sport and Recreation Strategy 2015-24: Background Report This document presents the relevant literature that has been reviewed, an assessment of the potential demand for sport and recreation in Port Phillip, analysis of the current supply of sport and recreation opportunities in Port Phillip, and outlines the findings from consultation with sports clubs, peak bodies, schools and the community. *It is important to note that this document attempts to display the most current information available at the time of production. As a result, there are some minor inconsistencies in the presentation of some data due to the lack of available updated information. -

Examining the Association Between Cycling Infrastructure and Cycling

Examining the association between cycling infrastructure and cycling: Baseline results from INTERACT Victoria By Melissa Tobin A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Kinesiology School of Human Kinetics and Recreation Memorial University of Newfoundland July 2020 St. John’s, Newfoundland & Labrador Abstract The majority of Canadians are not meeting physical activity guidelines. Implementing infrastructure that supports active transportation is an important intervention to increase population physical activity levels. The INTErventions, Research and Action in Cities Team (INTERACT), has the goal to advance research on the design of healthy and sustainable cities for all. My study is a sub-project of INTERACT and has three main objectives. The first objective is to determine whether participants support the All Ages and Abilities (AAA) Cycling Network. The second objective is to examine the association between exposure to the Pandora protected cycle track and physical activity levels and the third objective is to determine if there are gender differences in overall levels of physical activity. I hypothesized that participants would support the AAA Cycling Network and exposure to the Pandora protected cycle track would be associated with greater overall physical activity levels of residents who cycle at least once a month in Victoria. I also hypothesized that women would have lower levels of physical activity when compared to men. INTERACT recruited 281 people who completed online surveys; 149 of whom wore a Sensedoc (an accelerometer and global positioning system (GPS), for ten days to collect physical activity and spatial location data). -

Cycling Victoria State Facilities Strategy 2016–2026

CYCLING VICTORIA STATE FACILITIES STRATEGY 2016–2026 CONTENTS CONTENTS WELCOME 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 INTRODUCTION 4 CONSULTATION 8 DEMAND/NEED ASSESSMENT 10 METRO REGIONAL OFF ROAD CIRCUITS 38 IMPLEMENTATION PLAN 44 CYCLE SPORT FACILITY HIERARCHY 50 CONCLUSION 68 APPENDIX 1 71 APPENDIX 2 82 APPENDIX 3 84 APPENDIX 4 94 APPENDIX 5 109 APPENDIX 6 110 WELCOME 1 through the Victorian Cycling Facilities Strategy. ictorians love cycling and we want to help them fulfil this On behalf of Cycling Victoria we also wish to thank our Vpassion. partners Sport and Recreation Victoria, BMX Victoria, Our vision is to see more people riding, racing and watching Mountain Bike Australia, our clubs and Local Government in cycling. One critical factor in achieving this vision will be developing this plan. through the provision of safe, modern and convenient We look forward to continuing our work together to realise facilities for the sport. the potential of this strategy to deliver more riding, racing and We acknowledge improved facilities guidance is critical to watching of cycling by Victorians. adding value to our members and that facilities underpin Glen Pearsall our ability to make Victoria a world class cycling state. Our President members face real challenges at all levels of the sport to access facilities in a safe, local environment. We acknowledge improved facilities guidance is critical to adding value to our members and facilities underpin our ability to make Victoria a world class cycling state. Facilities not only enable growth in the sport, they also enable broader community development. Ensuring communities have adequate spaces where people can actively and safely engage in cycling can provide improved social, health, educational and cultural outcomes for all. -

Cycling Into the Future 2013–23

DECEMBER 2012 CYCLING INTO THE FUTURE 2013–23 VICTORIA’s cyCLING STRATEGY Published by the Victorian Government, Melbourne, December 2012. © State of Victoria 2012 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced in any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government Melbourne Printing managed by Finsbury Green For more information contact 03 9655 6096 PAGE III CYCLING INTO THE FUTURe 2013–23 VICTORIA’s CYCLING STRATEGY CONTENTS Minister’s foreword v Executive summary vi 1 Cycling in Victoria 1 2 Growing cycling in Victoria 5 Current cycling patterns 5 Potential growth 5 3 Benefits of cycling 8 Healthier Victorians 8 Better places to live 9 Stronger economy 9 Healthier environment 10 4 Strategic framework 11 Direction 1: Build evidence 12 Direction 2: Enhance governance and streamline processes 14 Direction 3: Reduce safety risks 16 Direction 4: Encourage cycling 20 Direction 5: Grow the cycling economy 22 Direction 6: Plan networks and prioritise investment 24 5 Implementation, monitoring and evaluation 29 Appendix 1: Cycling networks, paths and infrastructure 30 PAGE IV CYCLING INTO THE FUTURe 2013–23 VICTORIA’s CYCLING STRATEGY Some of our work in metropolitan Melbourne includes: > a new bridge on the Capital City Trail at Abbotsford > bike lanes along Chapel Street > extensions and improvements to the Federation Trail, Gardiner’s Creek Trail and Bay Trail on Beach Road > Jim Stynes Bridge for walking and cycling between Docklands and the CBD along the Yarra River > Heatherton Road off-road bike path from Power Road to the Dandenong Creek Trail > a bridge over the Maroondah Highway at Lilydale > bike connections to Box Hill and Ringwood > Parkiteer bike cages and bike hoops at 16 railway stations > Westgate Punt weekday services > bike paths along the Dingley Bypass, Stud Road, Clyde Road and Narre Warren – Cranbourne Road > bike infrastructure as part of the Regional Rail Link project > a new trail in association with the Peninsula Link. -

Dear Mayor Helps and Council Members, I Am Writing in Response

Dear Mayor Helps and Council members, I am writing in response to the city budget, because I am concerned that funding is not properly allocated to address the needs of Victoria and its residents. I feel that a disproportionate amount of City money goes toward the Police -- while other city resources are underfunded -- and the police end up doing jobs they are not adequately prepared to do, which is ineffective and inefficient. Police Chief Elsner said in the Time Colonist (September 22, 2014) that “25 to 30 of what we do is actual law enforcement…But the rest of it, 75 or 80% of what we do is all about the social side…mental health, homelessness and addiction issues. That‟s what takes up the vast majority of our resources." Is this an appropriate use of police resources? Over the next few years, the police budget should gradually be re-allocated (not “cut”) to support the development of another set of institutions more appropriate to responding to these social issues in partnership with other local organizations, such as: Social housing (in partnership with the Greater Victoria Coalition to End Homelessness) Supervised Consumption Site (in partnership with VIHA) 24-hour mental health crisis team to replace police as first responders to citizens facing mental health crises (in partnership with VIHA). When Chief Elsner reports that 90% of his resources are spent on law enforcement, then City Council will know they have the right size police force doing the right job, and an equally effective and efficient set of institutions with the right training and skills to respond to social issues. -

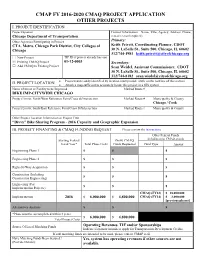

Cmap Fy 2016-2020 Cmaq Project Application Other Projects I

CMAP FY 2016-2020 CMAQ PROJECT APPLICATION OTHER PROJECTS I. PROJECT IDENTIFICATION Project Sponsor Contact Information – Name, Title, Agency, Address, Phone, Chicago Department of Transportation e-mail (e-mail required) Other Agencies Participating in Project Primary: CTA, Metra, Chicago Park District, City Colleges of Keith Privett, Coordinating Planner, CDOT Chicago 30 N. LaSalle St., Suite 500, Chicago, IL 60602 312/744-1981 [email protected] ☐ New Project TIP ID if project already has one ☒ Existing CMAQ Project 01-12-0003 Secondary: ☐ Add CMAQ to Existing Project Sean We idel, Assistant Commissioner, CDOT 30 N. LaSalle St., Suite 500, Chicago, IL 60602 312/744-8182 [email protected] II. PROJECT LOCATION • Projects not readily identified by location must provide a title on the last line of this section • Attach a map sufficient to accurately locate this project in a GIS system Name of Street or Facility to be Improved Marked Route # BIKE IMP-CITYWIDE CHICAGO Project Limits: North/West Reference Point/Cross St/Intersection Marked Route # Municipality & County Chicago / Cook Project Limits: South/East Reference Point/Cross St/Intersection Marked Route # Municipality & County Other Project Location Information or Project Title “Divvy” Bike Sharing Program - 2016 Capacity and Geographic Expansion III. PROJECT FINANCING & CMAQ FUNDING REQUEST Please review the instructions. Other Federal Funds Starting Federal (New) CMAQ Including prior CMAQ awards Fiscal Year* Total Phase Costs Funds Requested Fund Type Amount -

Student Cycling in Chicago,X-Default

Ride a Bike! A message from a cyclist - Mayor Richard M. Daley Bicycling is a great way to get around campus and around town. It's healthy, eco- nomical, environmentally friendly and a wonderful way to discover Chicago. From locking your bike to fixing a flat tire, you'll find all sorts of useful information inside this Student Cycling in Chicago book- let. Riding a bike as a student can lead to a life-long transportation choice that's good for you, your community and the enviroment. I invite you to review this booklet and discover for yourself why Chicago is a great city for bicycling. Richard M. Daley Mayor STUDENT CYCLING IN CHICAGO www.ChicagoBikes.org 1 Buying a Bike When buying a bike wear clothes like the ones you plan to bike in regularly and take a test ride If your bike budget is like the riding you’ll do around school and the small consider buying a used bike. Used city. Also consider these things: bikes can be found at · What kind of riding you plan to do and what thrift shops and yard type of bike is best suited for you. s ale s for cheap. · The cost of the bike. WorkingBikesCooperative · The cost of a lock, lights, helmet and other has a used bike sale accessories like a rack and fenders. on weekends. Go to · Whether you can exchange parts for www.workingbikes.org better fit or use. for more information. · Guarantees and warranties on the purchase. If you plan to buy a · Bike shop quality and service. -

Newsletter September 2007

Newsletter October 2013 Boroondara BUG meetings are normally held on the 2nd Wednesday of each month except January. Our next meeting is on Wednesday 9th October. It will be held in the function room of the Elgin Inn, cnr Burwood Rd and Elgin St Hawthorn (Melway 45 B10). The meeting starts at 7.00pm. Some of us arrive around 6.30pm for a meal at the Elgin Inn before the meeting. The Boroondara BUG is a voluntary group working to promote the adoption of a safe and practical environment for utility and recreational cyclists in the City of Boroondara. We have close links with the City of Boroondara, Bicycle Network Victoria, and other local Bicycle Users Groups. Two of the positions on the Boroondara Bicycle Advisory Committee, which meets quarterly, are assigned to Boroondara BUG members. Boroondara BUG has a website at http://www.boroondarabug.org that contains interesting material related to cycling, links to other cycle groups, recent Boroondara BUG Newsletters and breaking news. Our email address for communications to the BUG is [email protected] We also have a Yahoo Group: Send a blank email to: [email protected] to receive notification when the latest monthly newsletter and rides supplement have been placed on the web site and details of our next meeting, and very occasional other important messages. All articles in this newsletter are the views and opinions of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of any other members of Boroondara BUG. All rides publicised in the Rides Supplement are embarked upon at your own risk. -

Pedestrian Plan Department of Transportation

Chicago Pedestrian Plan Department of Transportation DRAFT T ABLE OF C ON T EN T S Letter from the Mayor and Commissioner 7 What We Heard 10 Tools for Safer Streets 16 Safety 36 Connectivity 64 Livability 86 Health 96 Making It Happen 108 3 4 OFFICE OF THE MAYOR CITY OF CHICAGO 121 N. LaSalle Street • Chicago, Illinois 60602 www.cityofchicago.org • @chicagosmayor Dear Fellow Chicagoans, Chicago’s remarkable pedestrian streets make our city a place where people want to live, work and play. The pedestrian experience is critical to the city and its future. From the hundreds of thousands of people that walk in the Loop every day, to the millions of riders of our trains and buses, to the bustling activity in our neighborhood commercial corridors, the safety of pedestrians has always been a building block to the city’s success. We are committed to protecting these vital users of our transportation system; safe, pedestrian-friendly streets are a priority for my administration. We will create a culture of safety and respect by addressing street design and behavior through education, engineering and enforcement. Pedestrians are vital to both the economic and physical health of Chicago. Building more and better pedestrian spaces will help businesses grow and encourage further development of our workforce for those who want to live in a walkable, transit- friendly city. Additionally, by encouraging more people to walk, we can improve our collective health and quality of life. I am excited about the action steps identified in the Chicago Pedestrian Plan. This comprehensive agenda addresses all aspects of the city’s pedestrian experience.