Belonging to the Ages: the Enduring Relevance of Aaron Copland's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PENSION FUND BENEFIT CONCERT TUESDAY EVENING 5 AUGUST 1980 at 8:30 Flute Concerto, And, Most Recently, a Violin Concerto

PENSION FUND BENEFIT CONCERT TUESDAY EVENING 5 AUGUST 1980 at 8:30 flute concerto, and, most recently, a violin concerto. Mr. Williams has composed the music and served as music director for approximately sixty films, including lane Eyre, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, The Poseidon Adventure, The Towering Inferno, Earthquake, Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, and Dracula. He has recently completed his latest score for the sequel to Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back, and recorded it with the London Sym- phony Orchestra. For his work in films, Mr. Williams ha& received fourteen Academy Award nominations, and he has been awarded three Oscars: for his filmscore arrangement of Fiddler on the John Williams Roof, and for his original scores to Jaws John Williams was named the nine- and Star Wars.This year, he has won his teenth Conductor of the Boston Pops seventh and eighth Grammys: the on 10 January 1980. Mr. Williams was soundtrack of his score for Superman born in New York in 1932 and moved was chosen as best album of an original to Los Angeles with his family in 1948. movie or television score, and the He studied piano and composition at Superman theme was cited as the year's the University of California in Los best instrumental composition. In addi- Angeles and privately with Mario tion, the soundtrack album to Star Castelnuovo-Tedesco; he was also a Wars has sold over four million copies, piano student of Madame Rosina more than any non-pop album in Lhevinne at the Juilliard School in recording history. -

Library Congress

The Music Division of the Library Congress HAROLD SPIVACKE THE COLLECTION OF MUSIC in the Library of Congress antedates by many years the founding of the Music Divi- sion in 1897. There was a small but interesting section of books on music in Jefferson's library when it was acquired by Congress to re- place its library destroyed in the War of 1812. By the time the pres- ent main building was opened in 1897, there had accumulated in the Capitol a great number of pieces of music which had to be moved into the new building. During the subsequent six decades, this number increased almost tenfold and there are now over three million items in the custody of the Music Division. The services which developed as a result of this phenomenal growth are both complex and varied. This study, however, will be limited to a discussion of those special services and activities of the Music Division which are unusual in the library world, some of them the result of the special position of the Library of Congress and others the result of what might be called historical accident. There is an apparent reciprocity between the constituency which a library serves and its collections and services. The accumulation of a large quantity of a certain type of material will in itself frequently attract a new type of library user. The reverse is often true in that the growth of a certain type of musical activity in a community will lead a library to acquire the materials and develop the services neces- sary to support this activity. -

Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865)

Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865) Abraham Lincoln, 16th president of the rustratingly little is known about the life and career of Sarah United States, guided the nation through Fisher Ames. Born Sarah Clampitt in Lewes, Delaware, she its devastating Civil War and remains much beloved and honored as one of the moved at some point to Boston, where she studied art. She world’s great leaders. Lincoln was born in spent time in Rome, but whether she studied formally there Hardin (now Larue) County, Kentucky. He is not known. Wife of the portrait painter Joseph Alexander moved with his family to frontier Indiana in Ames, she produced at least five busts of President Lincoln, but the cir- 1816, and then to Illinois in 1830. After F serving four terms in the Illinois legislature, cumstances of their production are not well documented. While Ames Lincoln was elected as a Whig to the U.S. was able to patent a bust of the 16th president in 1866, the drawings were House of Representatives in 1846. He did not seek reelection and returned to Spring- later destroyed in a U.S. Patent and Trademark building fire. field, Illinois, where he established a As a nurse during the Civil War, Ames was responsible for the statewide reputation as an attorney. temporary hospital established in the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. Although unsuccessful as a Whig candi date for the U.S. Senate in 1855, Lincoln One source reports that through this position she knew Lincoln “in an was the newly formed Republican Party’s intimate and friendly way,” but she also might have met the president standard-bearer for the same seat three through her activity as an antislavery advocate.1 Regardless of the origin years later. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Abraham Lincoln Accounts of the Assassination

I! N1 ^C ^ w ^ 3> » 2 t* Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/accountsofassasseszlinc Accounts of the Assassination of Abraham Lincoln Stories of eyewitnesses, first-hand or passed down Surnames beginning with s-z From the files of the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection ll-zool , ' ozzii S^-^^Sj £«K>f^e.A)< Vol. IX.—No. 452.] NEW YOKE, SATURDAY, AUGUST 26, 1865. Entered according to Act ofX'ongress, in the Year 1865, by Harper <fc Brothers, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court for the Southern GEORGJ) N. SANDERS. George N. Sanders, the notorious rebel who across our northern border has been so long con- spiring against the Government, was born in Ken- tucky, which was also the native State of Jeep Davis. lie is between forty-five and fifty years of age, and has been for many years engaged in vis- ionary political schemes. Under Pierce and Bu- chanan he was happy enough to gain a brief offi- ei.il authority. The former appointed him Navy ^~~ ***" Agent at New York, and the latter Consul to Lon- don. In 1801 he returned to this country and em- ,/A- braced tin rebel cause. was engaged in several ^ He schemes for increasing the rebel navy, all of which failed. His supposed connection with the plot to murder President Lincoln, and with other infamous schemes against the peaceable citizens of the North, is too well known to require any comment. Within the last fortnight his name has again come promi- nently before the public. It has been reported that some dangerous fellows from the United States have been engaged in a plot for the abduction of the rebel agent. -

Abraham Lincoln – People, Places, Politics: History in a Box

Abraham Lincoln – People, Places, Politics: History in a Box Concordance to the Draft Rhode Island Grade Span Expectations for Civics & Government and Historical Perspectives Dear Educator, Thank you for taking the time to check out this great resource for your classroom. The Lincoln History Box is full of materials that can be used in a variety of ways. In order to ease your use of this resource, the RI ALBC has developed a concordance that links to the Civics GSEs and to potential lesson topics for the various sections of the box. The concordance contains several sections that each correspond to a certain resource. The suggested Civics GSEs listed next to each resource are meant as a springboard for developing lessons using that particular material, as is the list of potential lesson topics. When developing a lesson using the Civics GSEs, it is recommended to focus on or teach to one particular GSE. We hope that you enjoy using this rich resource in your classroom. Please contact us if you have any questions regarding the History Box or this concordance. Sincerely, The Rhode Island Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission The Rhode Island Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission – http://www.rilincoln200.org Questions? Please contact Lisa Maher at 401-222-8661 or [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Page Description 1 ………… Introduction 2 ………… Table of Contents 3 ………… Abraham Lincoln: People, Places, Politics – History in a Box … Section 1 4 ………… Abraham Lincoln: People, Places, Politics – History in a Box … Section 2 6 ………… Abraham -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Sccopland on The

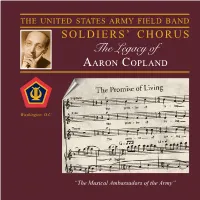

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND SOLDIERS’ CHORUS The Legacy of AARON COPLAND Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” he Soldiers’ Chorus, founded in 1957, is the vocal complement of the T United States Army Field Band of Washington, DC. The 29-member mixed choral ensemble travels throughout the nation and abroad, performing as a separate component and in joint concerts with the Concert Band of the “Musical Ambassadors of the Army.” The chorus has performed in all fifty states, Canada, Mexico, India, the Far East, and throughout Europe, entertaining audiences of all ages. The musical backgrounds of Soldiers’ Chorus personnel range from opera and musical theatre to music education and vocal coaching; this diversity provides unique programming flexibility. In addition to pre- senting selections from the vast choral repertoire, Soldiers’ Chorus performances often include the music of Broadway, opera, barbershop quartet, and Americana. This versatility has earned the Soldiers’ Chorus an international reputation for presenting musical excellence and inspiring patriotism. Critics have acclaimed recent appearances with the Boston Pops, the Cincinnati Pops, and the Detroit, Dallas, and National symphony orchestras. Other no- table performances include four world fairs, American Choral Directors Association confer- ences, music educator conven- tions, Kennedy Center Honors Programs, the 750th anniversary of Berlin, and the rededication of the Statue of Liberty. The Legacy of AARON COPLAND About this Recording The Soldiers’ Chorus of the United States Army Field Band proudly presents the second in a series of recordings honoring the lives and music of individuals who have made significant contributions to the choral reper- toire and to music education. -

New Morning for the World: a Landmark Commission by the Eastman School of Music

New Morning for the World: A Landmark Commission by the Eastman School of Music Introductory reflections by Paul J. Burgett University of Rochester Vice President Robert Freeman, Director of the Eastman School of Music from 1972 to 1996, is an avid baseball fan. He is fond of recounting that he became especially impressed by the Pittsburgh Pirates while watching the 1979 World Series at home, with his wife Carol, in which the Pirates, trailing the Baltimore Orioles three games to one, rebounded and won the Series in game seven. Bob marveled especially at the grit, inspiring spirit, elegant demeanor, and warm mellifluous voice of the Pirates’ iconic captain and that year’s MVP, Willie Stargell. The wheels of invention began to turn in Freeman’s mind. If Stargell and his teammates could fill a baseball stadium with 59,000 fans for a game, he mused, might Stargell, whose very gracious manner and resonant baritone voice, together with a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer from the Eastman School’s faculty, collaborate in a musical masterpiece to fill American concert halls that would draw thousands of baseball and music enthusiasts? And could they parlay their collective expertise and visibility to draw attention to one of the most critical social movements of the time, the Civil Rights movement? At Freeman’s initiative, AT&T commissioned Joseph Schwantner, professor of composition at Eastman, to create a major work for orchestra and narrator, the texts of which were taken from speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Thus was New Morning for the World born. The piece received its world premiere in 1983 to a full house at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. -

William Schuman: the Witch of Endor William Schuman (1910-1992)

WILLIAM SCHUMAN: THE WITCH OF ENDOR WILLIAM SCHUMAN (1910-1992) JUDITH, CHOREOGRAPHIC POEM [1] JUDITH, CHOREOGRAPHIC POEM (1949) 21:20 [2] NIGHT JOURNEY (1947) 20:34 NIGHT JOURNEY THE WITCH OF ENDOR (1965) THE WITCH OF ENDOR [3] Part I 6:39 [4] Part II 8:09 [5] Part III 8:00 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [6] Part IV 8:21 Gil Rose, conductor [7] Part V 8:35 TOTAL 81:41 COMMENT William Schuman to Fanny Brandeis November 30, 1949 About three years ago I had the privilege of collaborating with Miss Graham on the work known as Night Journey which was commissioned by the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation in the Library of Congress, and was first performed on May3 , 1947 at the Harvard Symposium on Music Criticism. Working with Martha Graham was for me a most rewarding artistic venture and is directly responsible for the current collaboration. When I received a telephone call last spring from Miss Graham informing me that the Louisville Orchestra would commission a composer of her choice for her engagement, I had no inten- tion of adding to my already heavy commitments. However, as the telephone conversation progressed and as the better part of an hour was consumed, my resistance grew weaker and suddenly I found myself discussing the possible form the work could take. Actually, my reason for wanting to do the work was not only the welcome opportunity of writing another piece for Miss Graham, but also the opportunity of employing the full OGRAPHY BY MARTHA GRAHAM. MARTHA BY OGRAPHY resources of the modern symphony orchestra for a choreographic composition. -

Benny Goodman's Band As Opening C Fit Are Russell Smith, Joe Keyes, Miller Band Opened a Week Ago Bassist

orsey Launches Brain Trust! Four Bands, On the Cover Abe Most, the very fine fe« Three Chirps Brown clarinet man. just couldn't mm up ’he cornfield which uf- 608 S, Dearborn, Chicago, IK feted thi» wonderful opportunity Entered as «cwwrf Hom matter October 6.1939. at the poet oHice at Chicano. tllinou, under the Act of March 3, 1379. Copyright 1941 Taken Over for shucking. Lovely gal io Betty Bn Down Beat I’ubliAing Co., Ine. Janney, the Brown band'* chirp New York—With the open anil rumored fiancee of Most. ing of his penthouse offices Artene Pie- on Broadway and the estab VOL. 0. NO. 20 CHICAGO, OCTOBER 15, 1941 15 CENTS' lishment of his own personal management bureau, headed by Leonard Vannerson and Phil Borut, Tommy Dorsey JaeÆ Clint Brewer This Leader's Double Won Five Bucks becomes one of the most im portant figures in the band In Slash Murder business. Dorsey’s office has taken New York—The mutilated body of a mother of two chil- over Harry James’ band as Iren, found in a Harlem apartment house, sent police in nine well as the orks of Dean Hud lates on a search for Clinton P. Brewer last week. Brewer is son, Alex Bartha and Harold ihe Negro composer-arranger who was granted a parole from Aloma, leader of small “Hawaiian” style combo. In Addi the New Jersey State Penitentiary last summer after he com tion. Dorsey now is playing father posed and arranged Stampede in G-Minor, which Count to three music publishing houses, the Embassy, Seneca and Mohawk Ie’s band recorded.