Open PDF 267KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESS RELEASE IMMEDIATE RELEASE Mayors Lead the Way On

PRESS RELEASE IMMEDIATE RELEASE Mayors lead the way on fixing Northern transport Northern Metro Mayors Andy Burnham, Tracy Brabin, Steve Rotheram, Jamie Driscoll and Dan Jarvis have joined forces to stand up for passengers and set out their vision for transport in the North. The Northern Transport Summit brought together business and political leaders from across the region to shape future plans to build a safe, efficient, clean, sustainable and accessible transport system which will form the foundations to rebuild the North’s full economic potential. Experts rallied for investment in infrastructure and putting connectivity at the heart of the levelling up agenda. Including calls to build back better transport to reduce the inequalities between passengers in the North and South and improve access to job opportunities across the region. There was also a focus on accelerating a green recovery from the pandemic and investing in decarbonisation of road and air travel. From improving buses to getting more commuters on bikes, experts discussed how to rebuild confidence in public transport and make it the green, clean and affordable option for both work and leisure journeys. Andy Burnham, Mayor of Greater Manchester, said: “We know that fully-integrated and accessible transport networks are the foundation for social and economic prosperity. That’s why I recently announced a transport revolution to deliver for the people of Greater Manchester. “Affordable and reliable journeys, including daily caps where a single bus journey from Harpurhey in Greater Manchester should cost the same as one in Haringey, London. People should be able to move seamlessly across the city-region on buses, trams and trains with bike hire schemes and walking and cycling corridors. -

Review Report Launch Programme and Agenda

1 Introduction Covid-19 has highlighted health inequalities faced by Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities and colleagues. The pandemic has also drawn attention to the impact of systemic racism on people’s lives. The West Yorkshire and Harrogate Health and Care Partnership (WY&H HCP) recognised the opportunity to address these issues, establishing a commission independently chaired by Professor Dame Donna Kinnair, Chief Executive and General Secretary of the Royal College of Nursing, a leading figure in national health and care policy. You can read more about Professor Dame Donna Kinnair on page 4. The review has been co-produced by leaders from the NHS, local government and the Voluntary and Community Sector (VCS); informed by the voices of those with lived experience. This session presents a one off opportunity to hear direct from review panel members and to find out more about the report recommendations, action plan and importantly the next steps for us all. It will be held digitally via Microsoft Teams. If you haven’t used Microsoft Teams before, this guidance explains how to join. All attendees are asked to please keep their microphones on mute whilst others are speaking. To join, please book your place on Eventbrite here by Wednesday 14 October 2020. 2 Today’s agenda 10.00am – 10.05am Hello and welcome. The importance of getting involved, my personal reflections as Chair and hopes for the future following the review Professor Dame Donna Kinnair (see Dame Donna’s biography on page 4) 10.05am – 10.10am Why it’s good -

Her Majesty's Government and Her Official Opposition

Her Majesty’s Government and Her Official Opposition The Prime Minister and Leader of Her Majesty’s Official Opposition Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP || Leader of the Labour Party Jeremy Corbyn MP Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury (Chief Whip). He will attend Cabinet Rt Hon Mark Spencer MP remains || Nicholas Brown MP Treasurer of HM Household (Deputy Chief Whip) Stuart Andrew MP appointed Vice Chamberlain of HM Household (Government Whip) Marcus Jones MP appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP appointed || John McDonnell MP Chief Secretary to the Treasury - Cabinet Attendee Rt Hon Stephen Barclay appointed || Peter Dowd MP Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury Kemi Badenoch MP appointed Paymaster General in the Cabinet Office Rt Hon Penny Mordaunt MP appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and Minister for the Cabinet Office Rt Hon Michael Gove MP remains Minister of State in the Cabinet Office Chloe Smith MP appointed || Christian Matheson MP Secretary of State for the Home Department Rt Hon Priti Patel MP remains || Diane Abbott MP Minister of State in the Home Office Rt Hon James Brokenshire MP appointed Minister of State in the Home Office Kit Malthouse MP remains Parliamentary Under Secretary of State in the Home Office Chris Philp MP appointed Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and First Secretary of State Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP remains || Emily Thornberry MP Minister of State in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Rt Hon James Cleverly MP appointed Minister of State in the Foreign -

THE ACTIVIST GMB News from Around the Region

theACTIVIST Issue 25: March 2018 GMB News From Around The Region In this issue Political Campaign Trail TeamBatley & Spen NHS Under Attack School Dinner Cap ON THE CAMPAIGN TRAIL WITH GMB YOUNG MEMBERS Polish Library On Saturday 24th February 2018, a group of GMB young members, activists and GMB staff GMB@TUC came together in the Batley and Spen Constituency to support two GMB backed candidates Equality Conference for the local elections in May. The 30-strong team were joined by Regional Secretary, Neil Having a Gas Derrick and Batley & Spen MP, Tracy Brabin, for a day of campaigning. #RunForJo The morning session kicked-off in Liversedge to campaign for Jude McKaig, with plenty of door-knocking and leaflet distribution. Then it was back to the GMB Activist Centre in Cleckheaton to meet up with Angela Rayner MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Education, PRIDE 2018 who came along to show her support for both candidates. Pride season is fast approaching and GMB will be at the events below: The afternoon campaigning session was held in Cleckheaton for Tom Kowalski, who is a York Pride 9th June (parade key-player on the GMB National and Regional Young Members’ Network. and stall) Leeds Pride 5th August Rachel Harrison, Regional Young Members’ Officer, commissioned black waterproof jackets (parade) and red tee-shirts especially for the day that carried the message Vote Labour and the Wakefield Pride 12th August GMB logo. (stall) Please circulate these dates to Speaking to The Activist, Rachel said: “Hundreds of doors were knocked on, leaflets your members and if you would delivered and potential voters spoken to. -

NEW SHADOW CABINET 2020 Who’S In, Who’S Out?

NEW SHADOW CABINET 2020 Who’s In, Who’s Out? BRIEFING PAPER blackcountrychamber.co.uk Who’s in and Who’s out? Sir Keir Starmer, newly elected Leader of the UK Labour Party, set about building his first Shadow Cabinet, following his election win in the Labour Party leadership contest. In our parliamentary system, a cabinet reshuffle or shuffle is an informal term for an event that occurs when the head of a government or party rotates or changes the composition of ministers in their cabinet. The Shadow Cabinet is a function of the Westminster system consisting of a senior group of opposition spokespeople. It is the Shadow Cabinet’s responsibility to scrutinise the policies and actions of the government, as well as to offer alternative policies. Position Former Post Holder Result of New Post Holder Reshuffle Leader of the Opposition The Rt Hon Jeremy Resigned The Rt Hon Sir Keir Starmer and Leader of the Labour Corbyn MP KCB QC MP Party Deputy Leader and Chair of Tom Watson Resigned Angela Raynor MP the Labour Party Shadow Chancellor of the The Rt Hon John Resigned Anneliese Dodds MP Exchequer McDonnell MP Shadow Foreign Secretary The Rt Hon Emily Moved to Lisa Nandy MP Thornberry MP International Trade Shadow Home Secretary The Rt Hon Diane Resigned Nick Thomas-Symonds MP Abbott MP Shadow Chancellor of the Rachel Reeves MP Duchy of Lancaster Shadow Justice Secretary Richard Burgon MP Left position The Rt Hon David Lammy MP Shadow Defence Secretary Nia Griffith MP Moved to Wales The Rt Hon John Healey MP Office Shadow Business, Energy Rebecca -

Regarding the Sale of Alcohol at 15 Branch Road Armley, I Am Writing to Object and Contest It Should Not Be Granted

From:Mudge, Peter Sent:25 May 2021 14:36:00 +0100 To:Deighton, Charlotte Subject:Amended Hi Charlotte, I realise one bit of my opposition to 15 Branch Rd is incorrect – where Alison Lowe mentions the 24 hr off licence has been closed. Here is a version with the erroneous bit removed. Can it still go without my phone number or email please. “Regarding the sale of alcohol at 15 Branch Road Armley, I am writing to object and contest it should not be granted. A general store concentrating on Lietuvaite - which I understand is a rye bread - would be most welcome, but the off-licence aspect would be exacerbation of Armley’s already nationally advertised drink problems. Crime & Disorder - The site is in one of the most problematic illegal drinking areas in Yorkshire and therefore the UK. Indeed in the national Phase 2 of the “UK Towns’ Fund”, the government is currently suggesting a combined project so they work with the public sector, businesses and community to find innovative solutions to problems faced in Armley town centre. Independent of this government involvement, asb in Armley escalated as current lockdowns eased. Consequently West Yorkshire Police and Leeds Anti-Social Behaviour team are undertaking a series of projects to combat crime and fear of crime. In a letter they distributed at the start of May to every business and household in the vicinity of Armley town centre their opening lines are: “Dear resident, business owner or proprietor, “We are aware of the history of high levels of anti-social behaviour in and around the Armley Town Street Area. -

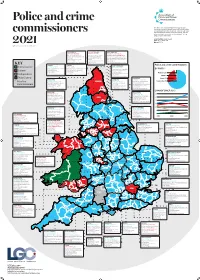

PCC Map 2021

Police and crime The APCC is the national body which supports police and crime commissioners and other local policing bodies across England and Wales to provide national leadership commissioners and drive strategic change across the policing, criminal justice and wider community safety landscape, to help keep our communities safe. [email protected] www.apccs.police.uk 2021 @assocPCCs © Local Government Chronicle 2021 NORTHUMBRIA SOUTH YORKSHIRE WEST YORKSHIRE KIM MCGUINNESS (LAB) ALAN BILLINGS (LAB) MAYOR TRACY BRABIN (LAB) First elected 2019 by-election. First elected 2014 by-election. Ms Brabin has nominated Alison Lowe Former cabinet member, Newcastle Former Anglican priest and (Lab) as deputy mayor for policing. Former City Council. deputy leader, Sheffield City councillor, Leeds City Council and chair of www.northumbria-pcc.gov.uk Council. West Yorkshire Police and Crime Panel. 0191 221 9800 www.southyorkshire-pcc.gov.uk 0113 348 1740 [email protected] 0114 296 4150 [email protected] KEY [email protected] CUMBRIA DURHAM Police and crime commissioners NORTH YORKSHIRE PETER MCCALL (CON) JOY ALLEN (LAB) Conservative PHILIP ALLOTT (CON)* First elected 2016. Former colonel, Former Durham CC cabinet member and Former councillor, Harrogate BC; BY PARTY Royal Logistic Corps. former police and crime panel chair. former managing director of Labour www.cumbria-pcc.gov.uk www.durham-pcc.gov.uk marketing company. 01768 217734 01913 752001 Plaid Cymru 1 www.northyorkshire-pfcc.gov.uk Independent [email protected] [email protected] 01423 569562 Vacant 1 [email protected] Plaid Cymru HUMBERSIDE Labour 11 LANCASHIRE CLEVELAND JONATHAN EVISON (CON) * Also fi re ANDREW SNOWDEN (CON) NORTHUMBRIA STEVE TURNER (CON) Councillor at North Lincolnshire Conservative 29 Former lead member for highways Former councillor, Redcar & Council and former chair, Humberside Police and Crime Panel. -

E-Review: February's By-Elections

reviewMarch 2017 www.hoddereducation.co.uk/politicsreview February’s by-elections CORUND/FOTOLIA Emma Kilheeney considers the results of the two February by-elections n two important by-elections on 23 February Labour lost the constituency of Copeland to the UKIP fails to steal Stoke IConservatives for the first time in over 80 years but held on to Stoke, defeating UKIP candidate and party When Tristram Hunt MP decided to end his political leader Paul Nuttall. career, and resign from his Stoke-on-Trent seat to become the director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Conservatives conquer Copeland Labour knew it would have a hard fight against UKIP. In Copeland the Conservatives celebrated becoming As 69% of the electorate in the Stoke constituency voted the first governing party since 1982 to gain a seat in to leave the EU last June, UKIP hoped to capitalise on a by-election. Conservative candidate Trudy Harrison the Brexit issue, and ran its party leader, Paul Nuttall, as defeated Labour, which had held the Copeland candidate. In fact UKIP failed to make significant gains seat since 1983 and its predecessor constituency on its performance here in the 2015 general election. Whitehaven since 1935. Jeremy Corbyn fought off The Labour candidate, and winner of the by- calls for his resignation after his party lost this seat in election, Gareth Snell was helped by the fact that Paul its heartland. Nuttall made a series of political gaffs including: Professor John Curtice, of Strathclyde University, • being unable to name the six towns that make up told the BBC that the Copeland result was the best by- Stoke election performance by a governing party — in terms • falsely claiming to have lost close personal friends in of the increase in its share of the vote — since January the Hillsborough disaster 1966. -

HBF Recommendations for the New Mayor of West Yorkshire.Pdf

Recommendations for the new Mayor of West Yorkshire The people of West Yorkshire will vote for their first Mayor on the 6 May. The affordability of housing and the type of homes that will be built over the next twenty years is very likely to be a key issue for the people of West Yorkshire. What the new mayor does in the next three years will be critical to shaping the future of housing in the region. Post-election, we look forward to working with the Mayor and the Combined Authority to help deliver all types of homes. However, it is clear that there are major challenges on the horizon. To ensure that the region builds the housing it needs and supports constituents, the Home Builders Federation recommends the following: • The new Mayor should commit to preparing a spatial development strategy that covers the five constituent local authorities of the West Yorkshire region. An up-to- date spatial plan for the city-region will coordinate land allocations for future housing supply with transport and environmental investment projects. • HBF acknowledges the difficulty associated with accommodating the 35% housing uplift for the cities of Leeds and Bradford. Bradford has recently declared that it is unable to meet this higher requirement in its new local plan. The new Mayor should encourage other local authorities in the wider combined authority family to cooperate to accommodate an element of this housing supply shortfall. • As owner-occupation remains the tenure of preference for most households, the Mayor should work with housebuilders to explore ways to support those who hope to become first-time buyers in West Yorkshire. -

Keir Starmer's Shadow Cabinet

Keir Starmer’s Shadow Cabinet Member of Parliament Shadow Cabinet Position Kier Starmer Leader of the Opposition Angela Rayner Deputy Leader and Chair of the Labour Party Anneliese Dodds Chancellor of the Exchequer Lisa Nandy Foreign Secretary Nick Thomas-Symonds Home Secretary Rachel Reeves Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster David Lammy Justice Secretary John Healey Defence Secretary Ed Miliband Business, Energy and Industrial Secretary Emily Thornberry International Trade Secretary Jonathan Reynolds Work and Pensions Secretary Jonathan Ashworth Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Rebecca Long-Bailey Education Secretary Jo Stevens Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Bridget Philipson Chief Secretary to the Treasury Luke Pollard Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Secretary Steve Reed Communities and Local Government Secretary Thangam Debbonaire Housing Secretary Jim McMahon Transport Secretary Preet Kaur Gill International Development Secretary Louise Haigh Northern Ireland Secretary (interim) Ian Murray Scotland Secretary Nia Griffith Wales Secretary Marsha de Cordova Women and Equalities Secretary Andy McDonald Employment Rights and Protections Secretary Rosena Allin-Khan Minister for Mental Health Cat Smith Minister for Young People and Voter Engagement Lord Falconer Attorney General Valerie Vaz Leader of the House Nick Brown Opposition Chief Whip Baroness Smith Shadow Leader of the Lords Lord McAvoy Lords’ Opposition Chief Whip Prepared by DevoConnect, April 2020. For more information contact [email protected] Keir -

Devolution Briefing Book

West Yorkshire Devolution briefing book Purpose of the briefing book The devolution deal is the beginning. Alongside significant immediate benefits it also positions West Yorkshire to benefit from new Mayoral funding streams and continue our discussions with Government over further powers and funding to achieve our ambitions. Combined authorities do not have a single model. The detail of their powers and funding arrangements are separate deals agreed and legislated in Parliament. Most Combined Area devolution deals focus on economic development, transport, skills, and land development. There are differences in what powers, funding and accountability comes with each change, in that some are statutory, some non-statutory, some are commitments, and not all have associated devolved funding. The Order that will be laid in Parliament establishes these differences, changes to current arrangements, and constitutional arrangements of the additional delegated functions to the Mayor and the Combined Authority. Existing powers and funding currently exercised and accessed by the Combined Authority remain unchanged. This briefing book acts as a reference guide to the devolution deal and Scheme to ensure consistency of understanding and to assist in briefings. It provides more information about the functions (powers and duties) and budgets of the devolution deal, and who is responsible for what: The Mayor or the West Yorkshire Combined Authority. It sets out what we know now, what is means for the region, and what opportunities it creates. It is split into seven sections that can be viewed in isolation, or as a complete article: 1. Introduction to the devolution deal 2. Governance 3. Transport 4. -

UNISON Active Magazine – Spring 2017

P14 NEW LOW FOR BOSSES P20 ‘THEY’RE INCREDIBLE’ P22 INSULT TO INJURY Cleaning company’s disgraceful attack Convenor Wendy Nichols pays an Ministers want injured people to on sacked Kinsley Academy strikers emotional visit to a Gambian school fund insurance company fat cats UNISON SPRING 2017 | ISSUE 26 | £3 THEACTIVE! MAGAZINE FOR MEMBERS IN YORKSHIRE AND HUMBERSIDE WWW.UNISON-YORKS.ORG.UK FROM ZERO TO HERO AN ABUSIVE RELATIONSHIP LEFT LAURA RILEY AT ROCK BOTTOM. NOW SHE HELPS OTHER WOMEN P08 UNISON:ESSENTIAL COVER FOR THOSE DELIVERING PUBLIC SERVICES DONCASTER RACEDAY SATURDAY AFTERNOON 5 AUGUST 2017 Exclusive special ticket offer for UNISON members Early booking incentive drinks voucher for ‘2 for 1’ Grandstand Tickets each of the first 400 ticket sales courtesy Total price £13 (2 tickets) of UNISON Living. On sale: from 1 February 2017 Offer closes: 5.00pm on 28 July 2017 Please note: there will be a To book tickets call 01302 304200 and quote £2.50 transaction charge per order except for purchases ‘the UNISON raceday offer’, your UNISON of four or less tickets. membership number or UNISON branch code. UPGRADE! Members can upgrade to two County Stand tickets for £30 (These are usually £32.50 each!) SPRING 2017 UNISON ACTIVE! 03 WELCOME UNISON:ESSENTIAL COVER OurUnion WE’LL STAND BY YOU FOR THOSE DELIVERING General Secretary Dave Prentis n diffi cult times, counted. achievement after PUBLIC SERVICES Regional Secretary our union has At a dark time sixty years. And John Cafferty Ialways pulled for those who value supporting the public Regional Convenor DAVE PRENTIS together and fought rights at work and service champions, Wendy Nichols GENERAL without whom our SECRETARY for our shared values.