CLASS DESCRIPTIONS Please Make Two Choices for Each Class Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

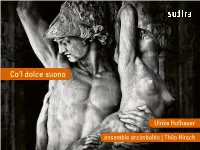

Digibooklet Co'l Dolche Suono

Co‘l dolce suono Ulrike Hofbauer ensemble arcimboldo | Thilo Hirsch JACQUES ARCADELT (~1507-1568) | ANTON FRANCESCO DONI (1513-1574) Il bianco e dolce cigno 2:35 Anton Francesco Doni, Dialogo della musica, Venedig 1544 Text: Cavalier Cassola, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch FRANCESCO DE LAYOLLE (1492-~1540) Lasciar’ il velo 3:04 Giovanni Camillo Maffei, Delle lettere, [...], Neapel 1562 Text: Francesco Petrarca, Diminutionen: G. C. Maffei 1562 ADRIANO WILLAERT (~1490-1562) Amor mi fa morire 3:06 Il secondo Libro de Madrigali di Verdelotto, Venedig 1537 Text: Bonifacio Dragonetti, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI (1492-~1565) Recercar Primo 0:52 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda pur della Prattica di Sonare il Violone d’Arco da Tasti, Venedig 1543 Recerchar quarto 1:15 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Regola che insegna sonar de viola d’archo tastada de Silvestro Ganassi dal fontego, Venedig 1542 GIULIO SEGNI (1498-1561) Ricercare XV 5:58 Musica nova accomodata per cantar et sonar sopra organi; et altri strumenti, Venedig 1540, Diminutionen*: A. Böhlen SILVESTRO GANASSI Madrigal 2:29 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 GIACOMO FOGLIANO (1468-1548) Io vorrei Dio d’amore 2:09 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543, Diminutionen*: T. Hirsch GIACOMO FOGLIANO Recercada 1:30 Intavolature manuscritte per organo, Archivio della parrochia di Castell’Arquato ADRIANO WILLAERT Ricercar X 5:09 Musica nova [...], Venedig 1540 Diminutionen*: Félix Verry SILVESTRO GANASSI Recercar Secondo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Lettione Seconda, Venedig 1543 SILVESTRO GANASSI Recerchar primo 0:47 Silvestro Ganassi, Regola Rubertina, Venedig 1542 JACQUES ARCADELT Quando co’l dolce suono 2:42 Il primo libro di Madrigali d’Arcadelt [...], Venedig 1539 Diminutionen*: T. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

High School Madrigals May 13, 2020

Concert Choir Virtual Learning High School Madrigals May 13, 2020 High School Concert Choir Lesson: May 13, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: students will learn about the history of the madrigal and listen to examples Bell Work ● Complete this google form. A Brief History of Madrigals ● 1501- music could be printed ○ This changed the game! ○ Reading music became expected ● The word “Madrigal” was first used in 1530 and was for musical settings of Italian poetry ● The Italian Madrigal became popular because the emphasis was on the meaning of the text through the music ○ It paved the way to opera and staged musical productions A Brief History of Madrigals ● Composers used text from popular poets at the time ● 1520-1540 Madrigals were written for SATB ○ At the time: ■ Cantus ■ Altus ■ Tenor ■ Bassus ○ More voices were added ■ Labeled by their Latin number ● Quintus (fifth voice) ● Sextus (sixth voice) ○ Originally written for 1 voice on a part A Brief History of Madrigals Homophony ● In the sixteenth century, instruments began doubling the voices in madrigals ● Madrigals began appearing in plays and theatre productions ● Terms to know: ○ Homophony: voices moving together with the same Polyphony rhythm ○ Polyphony: voices moving with independent rhythms ● Early madrigals were mostly homophonic and then polyphony became popular with madrigals A Brief History of Madrigals ● Jacques Arcadelt (1507-1568)was an Italian composer who used both homophony and polyphony in his madrigals ○ Il bianco e dolce cigno is a great example ● Cipriano de Rore -

Exploring Implications of the Double Attribution of the Madrigal “Canzon Se L’Esser Meco” to Andrea Gabrieli and Orlande De Lassus

A 16th Century Publication Who-Dun-it: Exploring implications of the double attribution of the madrigal “Canzon se l’esser meco” to Andrea Gabrieli and Orlande de Lassus. Karen Linnstaedter Strange, MM A Double Attribution Why was a single setting of “Canzon se l’esser meco” published in 1584 and 1589 under different composers’ names? For centuries, music history has ascribed this setting of a text from a Petrarchan madrigale to either Orlande de Lassus or Andrea Gabrieli, depending on the publication. It has been assumed the two original publications contain distinct creations of “Canzon se l’esser meco,” and to support this confusion, slight differences in notation between the two modern editions induce an initial perception that the two pieces differ. (See Figures 1A & 1B.). With a few moments of comparison, one can see that the madrigal published under Orlande de Lassus’ name in 1584 is the same piece attributed to Andrea Gabrieli by a different publisher five years later. In fact, no difference exists in the original publications beyond incidental choices by the two publishers, such as the number of notes printed per line and the notation for repeated accidentals. 1 (See Figures 2-5 A & B.) Suppositions and Presumptions The exactness of the two publications provokes interesting questions about issues of personal composer relations and influence, study by copying, and misattribution. In exploring all the possibilities, some quite viable, others farfetched, we can perhaps gain a clearer overview of the issues involved. On the less viable side, perhaps the piece was written simultaneously by each composer and, through some miracle, the two pieces turned out to be exactly the same. -

Jonson's Masque of Blackness and Multicultural Approaches to Early Modern English Literature Kristin Mcdermott

Language Arts Journal of Michigan Volume 18 Article 5 Issue 1 Diversity 2002 "To blanch an Ethiop": Jonson's Masque of Blackness and Multicultural Approaches to Early Modern English Literature Kristin McDermott Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/lajm Recommended Citation McDermott, Kristin (2002) ""To blanch an Ethiop": Jonson's Masque of Blackness and Multicultural Approaches to Early Modern English Literature," Language Arts Journal of Michigan: Vol. 18: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.9707/2168-149X.1301 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Language Arts Journal of Michigan by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "To blanch an Ethiop": Jonson's Masque of Blackness and Multicultural Approaches to Early Modern English Literature Kristin McDermott Before joining the faculty ofCentral Michigan of Blackness, even though one would assume it University, I taught for eight years at Spelman offered an important chance to explore one of the College, a historically black college for women in earliest treatments of race in English Literature, Atlanta, Georgia. Teaching Early Modern English is not often studied in any but the most advanced Literature (which encompasses both the Medieval classes, for obvious reasons. Briefly, a masque is period and the 16th _17th centuries in England) a form of dramatic entertainment in which poetic presented some exciting challenges in a setting praises ofthe monarch, the court, and their values whose mission included both Women's Studies and are presented in a setting of music, dance, and an African-Diasporic approach to culture and elaborate scenery. -

02 Chapter 1 Stoessel

Prologue La harpe de melodie faite saunz mirancholie par plaisir doit bien cescun resjorr pour l'armonie orr, sonner et vei'r. J With the prior verses begins one of the most fascinating musical works in the ars subtilior style, composed by the master musician Jacob de Senleches. This composer, as his name suggests, was a native of northern France whose scant biographical details indicate he was a valued musician at courts in the south at Castile, Navarre and possibly Avignon.2 La harpe de melodie typifies several aspects of the present study. Firstly, its presence in a n1anuscripe copied in the city of Pavia in Lombardy indicates the cultivation of ostensibly French music in the ars subtilior style in northern Italy. Secondly, its musical notation contains novel, experimental notational devices and note shapes that parallel intellectual developments in other fields of culture in this period. I "The melodious harp made without melancholy to please, well may each person rejoice to hear, sing and hear its harmony." (All translations are mine, unless otherwise specified.) 2 The conclusion that Jacob de Senleches was a native of northern France is made on the premise that Senleches is the near-homophone of Senlecques, a village just south of Calais in the County of Artois. The only surviving archival evidence concerning Jacob de Senleches consists of a dispensation made at the Court of Navarre by Charles II of Navarre on 21 sl August, 1383 which speCifies: ... 100 libras a Jacomill de Sen/aches, juglar de harpe, para regresar a donde se encontraba el cardenal de Aragon, su maestro (" 100 libras for Jacob de Senleches, player of the harp, to return to where he was to meet the Cardinal of Aragon, his master."), Jlid. -

I T a L Y!!! for Centuries All the Greatest Musicians Throughout Europe (From Josquin Des Prez, Adrian Willaert, Orlando Di Lasso to Wolfgang A

Richie and Elaine Henzler of COURTLY MUSIC UNLIMITED Lead you on a musical journey through I T A L Y!!! For centuries all the greatest musicians throughout Europe (from Josquin des Prez, Adrian Willaert, Orlando di Lasso to Wolfgang A. Mozart and so many others) would make a pilgrimage to Italy to hear and learn its beautiful music. The focus of the day will be music of the Italian Renaissance and its glorious repertoire of Instrumental and Vocal Music. Adrian Willaert, although from the Netherlands, was the founder of the Venetian School and teacher of Lasso, and both Gabrielis. The great Orlando di Lasso (from Flanders) spent 10 years in Italy working in Ferrara, Mantua, Milan, Naples and Rome where he worked for Cosimo I di Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. We’ll also play works by Andrea Gabrieli (uncle of Giovanni). In 1562 Andrea went to Munich to study with Orlando di Lasso who had moved there earlier. Andrea became head of music at St Marks Cathedral in Venice. Giovanni Gabrieli studied at St. Marks with his uncle and in 1562 also went to Munich to study under Lasso. Giovanni’s music became the culmination of the Venetian musical style. Lasso returned to Italy in 1580 to visit Italy and encounter the most modern styles and trends in music. Also featured will be Lodovico Viadana who composed a series of Sinfonias with titles of various Italian cities such as Bologna, Ferrara, Florence, Rome, Padua, Parma, Mantua, Venice and more. These city states are also associated with the delicious food of Italy, some of which we’ll incorporate into the lunch offering. -

Direction 2. Ile Fantaisies

CD I Josquin DESPREZ 1. Nymphes des bois Josquin Desprez 4’46 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 2. Ile Fantaisies Josquin Desprez 2’49 Ensemble Leones Baptiste Romain: fiddle Elisabeth Rumsey: viola d’arco Uri Smilansky: viola d’arco Marc Lewon: direction 3. Illibata dei Virgo a 5 Josquin Desprez 8’48 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 4. Allégez moy a 6 Josquin Desprez 1’07 5. Faulte d’argent a 5 Josquin Desprez 2’06 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction 6. La Spagna Josquin Desprez 2’50 Syntagma Amici Elsa Frank & Jérémie Papasergio: shawms Simen Van Mechelen: trombone Patrick Denecker & Bernhard Stilz: crumhorns 7. El Grillo Josquin Desprez 1’36 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction Missa Lesse faire a mi: Josquin Desprez 8. Sanctus 7’22 9. Agnus Dei 4’39 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 10. Mille regretz Josquin Desprez 2’03 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 11. Mille regretz Luys de Narvaez 2’20 Rolf Lislevand: vihuela 2: © CHRISTOPHORUS, CHR 77348 5 & 7: © HARMONIA MUNDI, HMC 901279 102 ITALY: Secular music (from the Frottole to the Madrigal) 12. Giù per la mala via (Lauda) Anonymous 6’53 EnsembleDaedalus Roberto Festa: direction 13. Spero haver felice (Frottola) Anonymous 2’24 Giovanne tutte siano (Frottola) Vincent Bouchot: baritone Frédéric Martin: lira da braccio 14. Fammi una gratia amore Heinrich Isaac 4’36 15. Donna di dentro Heinrich Isaac 1’49 16. Quis dabit capiti meo aquam? Heinrich Isaac 5’06 Capilla Flamenca Dirk Snellings: direction 17. Cor mio volunturioso (Strambotto) Anonymous 4’50 Ensemble Daedalus Roberto Festa: direction 18. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Antonio De Cabeçon (Castrillo Mota De Judíos 1510 – Madrid 1566)

Antonio de Cabeçon (Castrillo Mota de Judíos 1510 – Madrid 1566) Comiençan las canciones glosadas y motetes de a cinco Fol. 136-158v. from : Obras de Musica para Tecla, Arpa y Vihuela Madrid 1578 Second part: 13 canciones and 1 Fuga (or Tiento) in 5 voices transcribed for keyboard instrument or harp and arranged for recorders or other instruments with introduction and critical notes by Arnold den Teuling Keyboard instrument or harp 2017 1 2 Introduction to the edition of the remaining part of Antonio de Cabezón’s Obras de Musica para Tecla, Arpa y Vihuela, Madrid 1578 Hernando de Cabeçon (Madrid 1541-Valladolid 1602), as he spelled his name, published his father’s works in 1578, despite the year 1570 on the title page. The royal privilege for publication bears the date 1578 on the page which also contains the “erratas”. The Obras contain an extensive and very useful introduction in unnumbered pages, followed by 200 folio’s of printed music, superscribed in the upper margin “Compendio de Musica / de Antonio de Cabeçon.” A facsimile is in IMSLP. The first editor Felipe Pedrell (1841-1922), Hispaniae Schola Musica Sacra, Vols.3, 4, 7, 8, Barcelona: Juan Pujol & C., 1895-98, did not provide a complete edition, but a little more than half of it. He omitted the intabulations, “glosas”, of other composers, apparently objecting a lack of originality to them. He also gave an extensive introduction in Spanish and French. This edition may be found in IMSLP too. Pedrell stopped his complete edition after folio 68 (of 200), and made a selection of remaining works. -

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ......................................................................................................................................