Grammar Meets Genre: Reflections on the 'Sydney School'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April-2014.Pdf

BEST I FACED: MARCO ANTONIO BARRERA P.20 THE BIBLE OF BOXING ® + FIRST MIGHTY LOSSES SOME BOXERS REBOUND FROM MARCOS THEIR INITIAL MAIDANA GAINS SETBACKS, SOME DON’T NEW RESPECT P.48 P.38 CANELO HALL OF VS. ANGULO FAME: JUNIOR MIDDLEWEIGHT RICHARD STEELE WAS MATCHUP HAS FAN APPEAL ONE OF THE BEST P.64 REFEREES OF HIS ERA P.68 JOSE SULAIMAN: 1931-2014 ARMY, NAV Y, THE LONGTIME AIR FORCE WBC PRESIDENT COLLEGIATE BOXING APRIL 2014 WAS CONTROVERSIAL IS ALIVE AND WELL IN THE BUT IMPACTFUL SERVICE ACADEMIES $8.95 P.60 P.80 44 CONTENTS | APRIL 2014 Adrien Broner FEATURES learned a lot in his loss to Marcos Maidana 38 DEFINING 64 ALVAREZ about how he’s FIGHT VS. ANGULO perceived. MARCOS MAIDANA THE JUNIOR REACHED NEW MIDDLEWEIGHT HEIGHTS BY MATCHUP HAS FAN BEATING ADRIEN APPEAL BRONER By Doug Fischer By Bart Barry 67 PACQUIAO 44 HAPPY FANS VS. BRADLEY II WHY WERE SO THERE ARE MANY MANY PEOPLE QUESTIONS GOING PLEASED ABOUT INTO THE REMATCH BRONER’S By Michael MISFORTUNE? Rosenthal By Tim Smith 68 HALL OF 48 MAKE OR FAME BREAK? REFEREE RICHARD SOME FIGHTERS STEELE EARNED BOUNCE BACK HIS INDUCTION FROM THEIR FIRST INTO THE IBHOF LOSSES, SOME By Ron Borges DON’T By Norm 74 IN TYSON’S Frauenheim WORDS MIKE TYSON’S 54 ACCIDENTAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY CONTENDER IS FLAWED BUT CHRIS ARREOLA WORTH THE READ WILL FIGHT By Thomas Hauser FOR A TITLE IN SPITE OF HIS 80 AMERICA’S INCONSISTENCY TEAMS By Keith Idec INTERCOLLEGIATE BOXING STILL 60 JOSE THRIVES IN SULAIMAN: THE SERVICE 1931-2014 ACADEMIES THE By Bernard CONTROVERSIAL Fernandez WBC PRESIDENT LEFT HIS MARK ON 86 DOUGIE’S THE SPORT MAILBAG By Thomas Hauser NEW FEATURE: THE BEST OF DOUG FISCHER’S RINGTV.COM COLUMN COVER PHOTO BY HOGAN PHOTOS; BRONER: JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BOY/GETTY IMAGES BOY/GETTY JEFF BOTTARI/GOLDEN BRONER: BY HOGAN PHOTOS; PHOTO COVER By Doug Fischer 4.14 / RINGTV.COM 3 DEPARTMENTS 30 5 RINGSIDE 6 OPENING SHOTS Light heavyweight 12 COME OUT WRITING contender Jean Pascal had a good night on 15 ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES Jan. -

Jeff Fenech V Azumah Nelson, Princess Park, Melbourne 1992 The

1 Jeff Fenech v Azumah Nelson, Princess Park, Melbourne 1992 The crowd here at Melbourne’s Princess Park is restless. The main event, Azumah Nelson versus Jeff Fenech for the world light-weight championship, is due to start at 2 p.m. It has been raining steadily since the program of preliminary bouts commenced at 11 a.m. Now, one hour before fight time, Australian Spike Cheney is boxing Argentinean Juan Rodrigez in the final preliminary. Cheney is a skillful boxer, but it‟s like watching a comedian tell old jokes. The crowd can’t wait for him to finish. “Put him away Spike,” yells one hairy gap toothed individual. “Send him back home to Argentina in a box,” yells another tattooed behemoth. A boxing crowd is not a good place to find the new age sensitive male. “Send, that bloody Argentinean, back to the Falklands” gets a few laughs from the politically incorrect crowd. But “Spike him Cheney,” gets a mass groan for the budding Grouch Marx guzzling his beer two rows back. Not all boxing spectators have violent dispositions and racist tendencies. Boxings primeval brutality and flamboyant showmanship, also attracts the rich and famous. Media magnate Kerry Packer and actor Paul Hogan are here today, along with many authentic examples James of the Aussie Male yobbo. Amongst this yobbo fraternity it is interesting to see how body building has taken the place of tattoos as the symbol of Aussie male machismo. Tatoos haven‟t disappeared. There are still plenty of snakes on arms, spider web elbows and HATE inscribed knuckles. -

Boxing, Governance and Western Law

An Outlaw Practice: Boxing, Governance and Western Law Ian J*M. Warren A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Human Movement, Performance and Recreation Victoria University 2005 FTS THESIS 344.099 WAR 30001008090740 Warren, Ian J. M An outlaw practice : boxing, governance and western law Abstract This investigation examines the uses of Western law to regulate and at times outlaw the sport of boxing. Drawing on a primary sample of two hundred and one reported judicial decisions canvassing the breadth of recognised legal categories, and an allied range fight lore supporting, opposing or critically reviewing the sport's development since the beginning of the nineteenth century, discernible evolutionary trends in Western law, language and modern sport are identified. Emphasis is placed on prominent intersections between public and private legal rules, their enforcement, paternalism and various evolutionary developments in fight culture in recorded English, New Zealand, United States, Australian and Canadian sources. Fower, governance and regulation are explored alongside pertinent ethical, literary and medical debates spanning two hundred years of Western boxing history. & Acknowledgements and Declaration This has been a very solitary endeavour. Thanks are extended to: The School of HMFR and the PGRU @ VU for complete support throughout; Tanuny Gurvits for her sharing final submission angst: best of sporting luck; Feter Mewett, Bob Petersen, Dr Danielle Tyson & Dr Steve Tudor; -

6 Diciembre 2015 Ingles.Cdr

THE DOORS TO LATIN AMERICA, arrival of the Spanish on the XVI Century. TIJUANA B.C. , HOST VENUE OF January 2016 will be an spectacular year, the second World Boxing Council female OUR NEXT FEMALE CONVENTION convention will be hosted on this magnificent place. “Here starts our homeland” that’s Tijuana´s motto, it is the first Latin America city that The greatest female fighters will travel to shares border with San Diega, US anf is the Tijuana with the main goal of spreading and fifth most populated city of Mexico having keep developing this sport as we are able to more than 1, 600,000 habitants on it. enjoy all of its cultural and historic attractions. Tijuana is a city of great commercial and cultural activity, its history began with the Editorial Index Future fights WBC Emerald Belt May-Pac Roman Gonzalez Golovkin Viktor Postol Jorge Linares Zulina Muñoz Mikaela Lauren Erica Farias Alicia Ashley Ibeth Zamora Yessica Chavez Soledad Matthysse Leo Santa Cruz becomes Diamond champion Francisco Vargas Directorio: Saul Alvarez “WBC Boxing World” is the official magazine of the World Boxing Council. Floyd´s final Hurrah . Executive Director WBC Cares Mauricio Sulaimán. WBC Annual Convention Subdirector Víctor Silva. Knowing a Champion: Deontay Wilder Marketing Manager José Antonio Arreola Sulaimán Muhammad Ali Honored Managing Editor Mauricio Sulaiman is presented with the keys to the Francisco Posada Toledo city of Miami Traducción PRESIDENT DANIEL ORTEGA: a great supporter of Paul Landeros / James Blears Nicaraguan boxing Design Director Alaín -

Joes-Newsletter-Nov13

JOE’S BOXING SYDNEY NOVEMBER 2013 WWW.JOESBOXING.COM.AU 20/118 QUEENS RD FIVE DOCK FIVE DOCK NSW Celebrating 10 years of the Joe’s Boxing Brand & Logo Coming Up Saturday 9th to Sunday 10th Our annual fight night is an opportunity for November Rylstone Camp students to show their Saturday November 16th Joe’s skills and for those Boxing annual Fight Night red shirts participating 7pm the finale of our grad- ing system allowing Thursday 5th December last them to graduate after shirt promotion 2013. completing the 3 x 2 minute contest to their Thursday 19th December last black shirt and be class 2013. immortalized on our honour board for all First Class for 2014 Tuesday time. Each contest is 7th January 7pm judged by the specta- tors which encour- ages participants to Rylstone Pre-fight Night invite as many friends Camp 9th & 10th November . and family to the event. Trophies are My hope is that everyone who given for participation makes the journey through to and special event Blacks Shirt will attend one of my trophies and a cham- boxing camps. Driving tractors, pionship belt are Archery, golf, rock climbing & awarded to the best abseiling and even boxing can be on fighters on the night. the menu along with amazing stars This is also our major and open fire. Five Star camping fundraising event for the sleep in beds , Good ablution facili- year tickets are only $25 ties and everything including food on the night ($20 pre- provided. $25 per person for camp sold) and include much! share transport costs . -

Ring Magazine

The Boxing Collector’s Index Book By Mike DeLisa ●Boxing Magazine Checklist & Cover Guide ●Boxing Films ●Boxing Cards ●Record Books BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INSERT INTRODUCTION Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 2 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INDEX MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS Ring Magazine Boxing Illustrated-Wrestling News, Boxing Illustrated Ringside News; Boxing Illustrated; International Boxing Digest; Boxing Digest Boxing News (USA) The Arena The Ring Magazine Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Digest Fight game Flash Bang Marie Waxman’s Fight Facts Boxing Kayo Magazine World Boxing World Champion RECORD BOOKS Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 3 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK RING MAGAZINE [ ] Nov Sammy Mandell [ ] Dec Frankie Jerome 1924 [ ] Jan Jack Bernstein [ ] Feb Joe Scoppotune [ ] Mar Carl Duane [ ] Apr Bobby Wolgast [ ] May Abe Goldstein [ ] Jun Jack Delaney [ ] Jul Sid Terris [ ] Aug Fistic Stars of J. Bronson & L.Brown [ ] Sep Tony Vaccarelli [ ] Oct Young Stribling & Parents [ ] Nov Ad Stone [ ] Dec Sid Barbarian 1925 [ ] Jan T. Gibbons and Sammy Mandell [ ] Feb Corp. Izzy Schwartz [ ] Mar Babe Herman [ ] Apr Harry Felix [ ] May Charley Phil Rosenberg [ ] Jun Tom Gibbons, Gene Tunney [ ] Jul Weinert, Wells, Walker, Greb [ ] Aug Jimmy Goodrich [ ] Sep Solly Seeman [ ] Oct Ruby Goldstein [ ] Nov Mayor Jimmy Walker 1922 [ ] Dec Tommy Milligan & Frank Moody [ ] Feb Vol. 1 #1 Tex Rickard & Lord Lonsdale [ ] Mar McAuliffe, Dempsey & Non Pareil 1926 Dempsey [ ] Jan -

Backup of 5 Noviembre 2015 Ingles.Cdr

Editorial Yunnan Impression Show Index Future fights Linares will continue in the Lightweight division Andrzej Fonfara defeats Nathan Cleverly in a pummel war "Chocolatito" melts Brian Golovkin TKO´s Lemieux Viktor Postol, New Superlight World Champion WBC Cares in Kunming, China Kunming World Convention Knowing a Champion: Leo Santa Cruz The magic of a Convention Is Callum Smith The One? 1990 Chávez vs Taylor The Clowning Glory The WBC unites with Mexico City to combat breastcancer Muhammad Ali honored at fortieth Anniversary of Directorio: the Thrilla in Manila “WBC Boxing World” is the official Dodge that! "Great balls of fire" hurled by Cotto magazine of the World Boxing Council. "Macho" Camacho, a candidate for International Executive Director Boxing Hall of Fame Mauricio Sulaimán. Great Year for women´s boxing Subdirector Víctor Silva. World Champions Marketing Manager José Antonio Arreola Sulaimán Managing Editor Francisco Posada Toledo Traducción Paul Landeros / James Blears Design Director Alaín M. Flores Photos Naoki Fukuda Sumio Yamada Alma Montiel José Rodríguez Contributing Editors Víctor Cota (WBC Historian) José Antonio Arreola Sulaiman Juan Pereira James Blears Jamie Parry and Robbie Oliver Santa Cruz Paulina Brindis Our newest diamond Champion Dear Friends. The most important event of the WBC has taken place. Our annual Convetion in Kunming China, was a great and memorable success. Regarding ring activity, Jorge Linares, Roman Gonzalez and Gennady Golovkin defended their respective crowns with style, and also a new name is included in the WBC chárter of champions...Viktor Postol . In this edition of the magazine you will learn more of these hard hitting developments. -

October 4, 2014 This Will Be Wbc’S 1, 869 Championship Title Fight in the 52 Years History of the Wbc Reginaldo & Osvaldo Kuchle / Promociones Del Pueblo Presents

WBC FEATHERWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP BOUT CANCHA DE USOS MULTIPLES PRADERAS DE VILLA LOS MOCHIS, SINALOA, MEXICO OCTOBER 4, 2014 THIS WILL BE WBC’S 1, 869 CHAMPIONSHIP TITLE FIGHT IN THE 52 YEARS HISTORY OF THE WBC REGINALDO & OSVALDO KUCHLE / PROMOCIONES DEL PUEBLO PRESENTS: JHONNY GONZALEZ JORGE ARCE (MEXICO) WBC CHMAPION (MEXICO) WBC CHALLENGER Nationality: Mexican Nationality: Mexico Date of Birth: September 15, 1981 Date of Birth: July 27, 1979 Birthplace: Pachuca, Hidalgo Birthplace: Los Mochis, Sinaloa Residence: Mexico City Residence: Los Mochis, Sinaloa Record: 56-8-0, 47 KO’s Record: 64-7-2, 49 KO’s Age: 33 Age: 35 Guard: Orthodox Guard: Orthodox Total rounds: 313 Total rounds: 426 Title Fights: 17 (13-4-0) Titles Fights: 25 (20-5-0) Manager: Ignacio Beristain Manager: Promoter: Promociones del Pueblo Promoter: Zanfer Promotions WBC´S FEATHERWEIGHT WORLD CHAMPIONS NAME PERIODO CHAMPION NAME PERIODO CHAMPION 1. DAVEY MOORE (US) + 1963 25. ALEJANDRO GONZALEZ (MEX) 1995 2. ULTIMINIO RAMOS (MEX) 1963 - 1964 26. MANUEL MEDINA (MEX) 1995 3. VICENTE SALDIVAR (MEX) + 1964 - 1967 27. LUISITO ESPINOSA (PHIL) 1995 - 1999 4. HOWARD WINSTONE (GALES) + 1968 28. CESAR SOTO (MEX) 1999 5. JOSE LEGRA (CUBA) 1968 - 1969 29. NASEEM HAMED (GB) 1999 6. JOHNNY FAMECHON (FRAN) 1969 - 1970 30. GUTY ESPADAS (MEX) 200 - 2001 7. VICENTE SALDIVAR (MEX) * + 1970 31. ERIK MORALES (MEX) 2001 - 2002 8. KUNIAKI SHIBATA (JAPAN) 1970 - 1972 32. MARCO A. BARRERA (MEX) 2002 9. CLEMENTE SANCHEZ (MEX) + 1972 33. ERIK MORALES (MEX) * 2002 - 2003 10. JOSE LEGRA (CUBA) * 1972 - 1973 34. INJIN CHI (KOREA) 2004 - 2006 11. EDER JOFRE (BRA) 1973 35. -

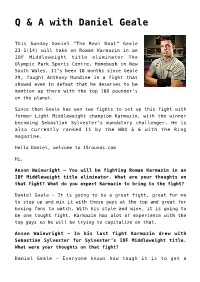

Q & a with Daniel Geale

Q & A with Daniel Geale This Sunday Daniel “The Real Deal” Geale 23-1(14) will take on Roman Karmazin in an IBF Middleweight title eliminator The Olympic Park Sports Centre, Homebush in New South Wales. It’s been 18 months since Geale 29, fought Anthony Mundine in a fight that showed even in defeat that he deserves to be mention up there with the top 160 pounder’s on the planet. Since then Geale has won two fights to set up this fight with former Light Middleweight champion Karmazin, with the winner becoming Sebastian Sylvester’s mandatory challenger. He is also currently ranked 11 by the WBO & 6 with the Ring magazine. Hello Daniel, welcome to 15rounds.com Hi, Anson Wainwright – You will be fighting Roman Karmazin in an IBF Middleweight title eliminator. What are your thoughts on that fight? What do you expect Karmazin to bring to the fight? Daniel Geale – It is going to be a great fight, great for me to step up and mix it with these guys at the top and great for boxing fans to watch. With his style and mine, it is going to be one tought fight. Karmazin has alot of experience with the top guys so he will be trying to capitalize on that. Anson Wainwright – In his last fight Karmazin drew with Sebastian Sylvester for Sylvester’s IBF Middleweight title. What were your thoughts on that fight? Daniel Geale – Everyone knows how tough it is to get a decision in Germany against a German, so I say he should have won that fight but I am glad that things have turned out this way because it is a great opportunity for me. -

May 9 Fight Is a Juicy Encore to May 2 P. 66 New Champ's

MAYWEATHER VS. PACQUIAO THE BIBLE OF BOXING MAY 2015 $8.95 MAY 9 FIGHT IS NEW CHAMP’S ENERGY LINGERS A JUICY ENCORE WILD RIDE TO 30 YEARS TO MAY 2 P. 66 THE TOP P. 72 LATER P. 78 MAY 2015 52 Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao probably never imagined when they looked like this that they would one FEATURES day meet in a superf ght. 66 ALVAREZ STEPS ASIDE MAYWEATHER VS. PACQUIAO Pages 34-65 CANELO MOVES JAMES KIRKLAND BOUT TO MAY 9 34 AT LONG LAST 52 LEGACIES ON THE LINE By Ron Borges THE SPORTÕS ICONIC STARS THE PERCEPTION OF THE WILL FINALLY DO BATTLE PRINCIPALS COULD CHANGE 72 WILDER ARRIVES By Norm Frauenheim By Bernard Fernandez NEW HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPÕS RAPID RISE TO THE TOP 40 CHA-CHING 58 BOOM OR BUST By D.C. Reeves THE MATCHUP WILL DESTROY MEGAFIGHTS THAT DID AND DIDNÕT ALL REVENUE RECORDS LIVE UP TO THE HYPE 78 HAGLER-HEARNS By Norm Frauenheim By Don Stradley THE EPIC WAR STILL REVERBERATES 30 YEARS LATER 46 HAVE THEY SLIPPED? 62 HEAD TO HEAD By Ron Borges TRAINERS ASSESS THE AGING THE RING COMPARES THE FIGHTERS BOXERS AND THE FIGHT IN 20 KEY CATEGORIES THE RING MAGAZINE By Keith Idec By Doug Fischer COVER ILLUSTRATION BY MIKE METH– MIKEMETH.NET 5.15 / RINGTV.COM 3 DEPARTMENTS 6 RINGSIDE 14 7 OPENING SHOT Recently retired Mikkel 8 COME OUT WRITING Kessler revealed his top opponents in “Best 11 ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES I Faced.” 14 BEST I FACED: MIKKEL KESSLER By Anson Wainwright 16 READY TO GRUMBLE By David Greisman 18 JABS AND STRAIGHT WRITES By Thomas Hauser 20 OUTSIDE THE ROPES By Brian Harty and Thomas Hauser 23 PERFECT EXECUTION -

Aussie Star Brock Jarvis Signs with Matchroom

AUSSIE STAR BROCK JARVIS SIGNS WITH MATCHROOM Australian Super-Featherweight sensation Brock Jarvis has signed a long term promotional deal with Eddie Hearn and Matchroom Boxing. The 23-year-old rising star has won all nineteen of his fights since joining the professional ranks in December 2015, with seventeen of those wins coming by way of knockout – the latest a sixth round stoppage of Nort Beauchamp in April to land the IBF Pan Pacific 130lbs title. Trained and managed by Jeff Fenech in Marrickville, Australia, the 5? 9? knockout artist has won titles at Bantamweight, Super-Bantamweight, Featherweight and Super-Featherweight – earning him a top 10 world ranking with the WBO at 126lbs and a top ten ranking with the IBF at 130lbs. “I’m just so excited for this opportunity to make my mark on the world stage,” said Jarvis. “This is a huge platform for me to build on and get me to where I want to be. “I’m not one for bad mouthing opponents or calling people out. I just get in there and let my fists do the talking. I’m working hard in the gym every day, learning so much and improving all the time. I know I’m getting closer to a World Title fight each time I step in the ring. “I am delighted to welcome Brock to the team as we begin our expansion into Australia,” said Matchroom Sport Chairman Eddie Hearn. “Brock has it all, he is ferocious in the ring and looks a million dollars, I truly believe this young man will become a global star with Matchroom and DAZN. -

L-G-0003887093-0002286367.Pdf

TYSON CELEBRITIES Series Editor: Anthony Elliott Published Ellis Cashmore, Backham Charles Lemert, Muhammad Ali Chris Rojek, Frank Sinatra Forthcoming Dennis Altman, Gore Vidal Cynthia Fuchs, Eminem Richard Middleton, John Lennon Daphne Read, Oprah Winfrey Nick Stevenson, David Bowie Jason Toynbee, Bob Marley TYSON Nurture of the Beast ELLIS CASHMORE polity Copyright © Ellis Cashmore 2005 The right of Ellis Cashmore to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 2005 by Polity Press Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK. Polity Press 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02148, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 0-7456-3069-3 ISBN: 0-7456-3070-7 (paperback) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 11 on 13 pt Palatino by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Books, Bodmin, Cornwall For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.polity.co.uk CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii one INTRODUCTION: I WILL KILL YOU. DO YOU UNDERSTAND THIS? 1 two IF YOU’D BE KIND ENOUGH, I’D LOVE TO DO IT AGAIN 13 three ARE YOU AN ANIMAL? IT DEPENDS 29 four LIKE WATCHING