The Collecting of Family Guy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postmodernism: the American T.V. Show, 'Family Guy, As a Politically Incorrect Document

Postmodernism: The American T.V. Show, 'Family Guy, As a Politically Incorrect Document Tyron Tyson Smith1; Ajit Duara2* 1Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2*Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2*[email protected] Abstract Postmodernism is a movement that grew out of modernism. Movements in art, literature, and cinema focused on a particular stance. The visual artists who created entertainment focused on expressing the creator herself/himself beginning from German expressionism to modernism, surrealism, cubism, etc. These art movements played an important part in what an artist (literature, art, and visual) portrayed to his or her audience. As perspectives played an important part, an understanding of what the artist needed to portray was critical. Modernism dealt with this portrayal, which came about due to the changes taking place in society. In terms of the industry, where the overall product dealt with features like individualism, experimentation and absurdity, modernism dealt with a need to overthrow past notions of what painting, literature, and the visual arts needed to be. "After World War II, the focus moved from Europe to the United States, and abstract expressionism (led by Jackson Pollock) continued the movement's momentum, followed by movements such as geometric abstractions, minimalism, process art, pop art, and pop music." Postmodernism helped do away with these shortcomings. An understanding of postmodernism is explored in this paper. The main point which sets it apart is concepts like pastiche, intersexuality, and spectacle. Concerning pop culture, an understanding of referencing is a constant trait used by postmodern art. -

44Th Hall of Fame Banquet

2011 44th Hall of Welcome Fame Banquet Tonight’s Jeanie Purcell-Hill, Hall of Fame Committee Chair Presentation of the Colors Goleta Boy Scouts Troop 105 Under the direction of Mr. Glenn Schiferl National Anthem Galen Callahan, recording artist Opening Remarks Catharine Manset Morreale, SBART President President’s Award Catharine Manset Morreale, SBART President Master of Ceremonies Marc “Cubby” Jacobs Program Hall of Fame Inductees Russ Hargreaves Memorial Award R.F. MacFarland Memorial Trophy Master Athlete Scholarships & Awards Phil Womble Awards Scholar-Athletes of the Year Special Olympics Mayor’s Trophy Coaches of the Year Athletes of the Year Closing Remarks e hope you will patronize our many business friends and sponsors listed in this Wprogram. It is their generosity, along with that of our guests this evening, that helps contribute to the development of our athletic community and to the lives of our student-athletes. Cover photos courtesy of Presidio Sports Program editing, layout and design by Cara M. Gamberdella, Board Member Printing by Boone Graphics Audio Visual by Jensens Audio Visual Slide show by Gene Deering 1 Jeanie Purcell-Hill, Chair 2011 Catharine Manset Morreale 2011 Ethel Byers Laurie Leighty Cara Gamberdella The Banquet Rick Wilson Pat Moorhouse-MacPhee Jason Wilson Committee Gene Deering Mike Warren Chris Casesbeer Bill Bertka Jerry Harwin Founder Founder Founders & Caesar Uyesaka Founder Past Presidents Jerry Harwin 1968-70 Paul Menzel 1993-95 Bill Bertka 1970-72 Joan Russell-Price 1995-97 Larry Crandell 1972-74 -

2K Unveils Stellar Video Game Line

2K Unveils Stellar Video Game Line-up for 2006 Electronic Entertainment Expo; Line-up Includes Highly- Anticipated Titles such as The Da Vinci Code(TM), Prey, Sid Meier's Civilization IV: Warlords and NBA 2K7 May 10, 2006 8:31 AM ET NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--May 10, 2006--2K and 2K Sports, publishing labels of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. (NASDAQ: TTWO), today announced a strong line-up for Electronic Entertainment Expo 2006 (E3) taking place at the Los Angeles Convention Center from May 10-12, 2006. From 2K, the line-up includes titles based on blockbuster entertainment brands such as The Da Vinci Code(TM) and Family Guy and popular comic book franchises The Darkness and Ghost Rider, as well as original next generation games such as Prey and BioShock. 2K is also featuring highly-anticipated titles from Firaxis Games, including Sid Meier's Civilization IV: Warlords and Sid Meier's Railroads! as well as the Firaxis and Firefly Studios collaboration title CivCity: Rome. Other eagerly awaited titles include Stronghold Legends(TM) along with Dungeon Siege II(R): Broken World(TM) and Dungeon Siege: Throne of Agony(TM), based on the acclaimed Dungeon Siege(R) franchise. In addition, the 2K Sports line-up features the next installments from top-rated franchises such as NHL 2K7, NBA 2K7 and College Hoops 2K7. 2K Line-up Includes: BioShock BioShock is an innovative role-playing shooter from Irrational Games who was named IGN's 2005 Developer of the Year. BioShock immerses players into a war-torn underwater utopia, where mankind has abandoned their humanity in their quest for perfection. -

Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in the Simpsons

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD Film Studies in the University of Hull by Jemma Diane Gilboy, BFA, BA (Hons) (University of Regina), MScRes (University of Edinburgh) April 2016 Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons by Jemma D. Gilboy University of Hull 201108684 Abstract (Thesis Summary) The objective of this thesis is to establish meme theory as an analytical paradigm within the fields of screen and fan studies. Meme theory is an emerging framework founded upon the broad concept of a “meme”, a unit of culture that, if successful, proliferates among a given group of people. Created as a cultural analogue to genetics, memetics has developed into a cultural theory and, as the concept of memes is increasingly applied to online behaviours and activities, its relevance to the area of media studies materialises. The landscapes of media production and spectatorship are in constant fluctuation in response to rapid technological progress. The internet provides global citizens with unprecedented access to media texts (and their producers), information, and other individuals and collectives who share similar knowledge and interests. The unprecedented speed with (and extent to) which information and media content spread among individuals and communities warrants the consideration of a modern analytical paradigm that can accommodate and keep up with developments. Meme theory fills this gap as it is compatible with existing frameworks and offers researchers a new perspective on the factors driving the popularity and spread (or lack of popular engagement with) a given media text and its audience. -

FAMILY GUY “The Glenn Beck Quagmire”

FAMILY GUY “The Glenn Beck Quagmire” Written by Marcos Luevanos Marcos Luevanos (626) 485-2140 [email protected] ACT ONE EXT./ESTAB. GRIFFINS’ HOUSE - DAY INT. GRIFFINS’ LIVING ROOM - SAME PETER blasts an air horn. PETER (CALLING UPSTAIRS) Hurry it up you guys! The world and I have waited long enough for “Pretty Woman 2: Reality Sets In.” INT. SUBURBAN HOME - MORNING (CUTAWAY) A sloppily dressed RICHARD GERE yells at a crying JULIA ROBERTS. TWO CHILDREN observe from the staircase. RICHARD GERE I’m not getting what the problem is. You knew I slept with hookers when you married me. (SCOFFS) That’s how we met! INT. GRIFFINS’ LIVING ROOM - DAY (BACK TO SCENE) The doorbell rings. Peter opens it to reveal an incredibly ill QUAGMIRE. PETER Hey Quagmire! (DISGUSTED) Whoa, you look worse than Lindsay Lohan in a well-lit room. FAMILY GUY - "The Glenn Beck Quagmire" 2. QUAGMIRE That bad, huh? I have an appointment at the free clinic but I can’t seem to, you know, see. Would you be able to give me a ride to the doctor? PETER Sure thing. I was running low on free condoms anyway. (CALLING UPSTAIRS) Hey slowpokes, eighty-six the movie, I’m taking Quagmire to get his junk checked out. LOIS (O.S.) What? PETER (CALLING UPSTAIRS) I said, I’m taking Quagmire to get his junk checked out. (NORMAL, TO QUAGMIRE) It is your junk, right? QUAGMIRE Right. PETER (CALLING UPSTAIRS) Yeah, it’s his junk. Quagmire smacks his forehead. FAMILY GUY - "The Glenn Beck Quagmire" 3. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

Televi and G 2013 Sion, Ne Graphic T 3 Writer Ews, Rad

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 6, 2012 2013 WRITERS GUILD AWARDDS TELEVISION, NEWS, RADIO, PROMOTIONAL WRITING, AND GRAPHIC ANIMATION NOMINEES ANNOUNCED Los Angeles and New York – The Writers Guild of Ameerica, West (WGAW) and the Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE) have announced nominaations for outstanding achievement in television, news, radio, promotional writing, and graphic animation during the 2012 season. The winners will be honored at the 2013 Writers Guild Awards on Sunday, February 17, 2013, at simultaneous ceremonies in Los Angeles and New York. TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Boardwalk Empire, Written by Dave Flebotte, Diane Frolov, Chris Haddock, Rolin Jones, Howard Korder, Steve Kornacki, Andrew Schneider, David Stenn, Terence Winter; HBO Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gouldd, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Becckett; AMC Game of Thrones, Written by David Benioff, Bryan Cogman, George R. R. Martin, Vanessa Taylor, D.B. Weiss; HBO Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm; Showtime Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Brett Johnson, Janeet Leahy, Victor Levin, Erin Levy, Frank Pierson, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner; AMC -more- 2013 Writers Guild Awards – TV-News-Radio-Promo Nominees Announced – Page 2 of 7 COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Kay Cannon, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Vali -

The Id, the Ego and the Superego of the Simpsons

Hugvísindasvið The Id, the Ego and the Superego of The Simpsons B.A. Essay Stefán Birgir Stefánsson January 2013 University of Iceland School of Humanities Department of English The Id, the Ego and the Superego of The Simpsons B.A. Essay Stefán Birgir Stefánsson Kt.: 090285-2119 Supervisor: Anna Heiða Pálsdóttir January 2013 Abstract The purpose of this essay is to explore three main characters from the popular television series The Simpsons in regards to Sigmund Freud‟s theories in psychoanalytical analysis. This exploration is done because of great interest by the author and the lack of psychoanalytical analysis found connected to The Simpsons television show. The main aim is to show that these three characters, Homer Simpson, Marge Simpson and Ned Flanders, represent Freud‟s three parts of the psyche, the id, the ego and the superego, respectively. Other Freudian terms and ideas are also discussed. Those include: the reality principle, the pleasure principle, anxiety, repression and aggression. For this analysis English translations of Sigmund Freud‟s original texts and other written sources, including psychology textbooks, and a selection of The Simpsons episodes, are used. The character study is split into three chapters, one for each character. The first chapter, which is about Homer Simpson and his controlling id, his oral character, the Oedipus complex and his relationship with his parents, is the longest due to the subchapter on the relationship between him and Marge, the id and the ego. The second chapter is on Marge Simpson, her phobia, anxiety, aggression and repression. In the third and last chapter, Ned Flanders and his superego is studied, mainly through the religious aspect of the character. -

Sunday Morning Grid 10/11/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

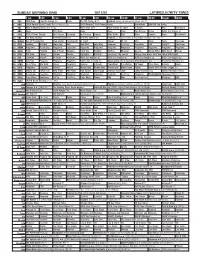

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/11/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC 2020 Roland-Garros Tennis Men’s Final. (6) (N) 2020 Women’s PGA Championship Countdown NASCAR Cup Series 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch AAA Sex Abuse 7 ABC News This Week News News News Sea Rescue Ocean World of X Games Å 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb AAA Silver Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Washington Football Team. (N) Å 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Abuse? Dr. Ho AAA Smile News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Cooking BISSELL More Hair AAA New YOU! Larry King Kenmore Paid Prog. Transform AAA WalkFit! Can’tHear 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Programa ·Solución! Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Queens Simply Ming Milk Street Nevens 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Curious Curious Highlights Biz Kid$ Easy Yoga: The Secret Change Your Brain, Heal Your Mind With Daniel 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Medicare NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Como dice el dicho (N) Suave patria (2012, Comedia) Omar Chaparro. -

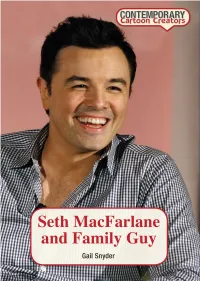

Family Guy: TV’S Most Shocking Show Chapter Three 39 Macfarlane Steps in Front of the Camera

CONTENTS Introduction 6 Humor on the Edge Chapter One 10 Born to Cartoon Chapter Two 24 Family Guy: TV’s Most Shocking Show Chapter Three 39 MacFarlane Steps in Front of the Camera Chapter Four 52 Expanding His Fan Base Source Notes 66 Important Events in the Life of Seth MacFarlane 71 For Further Research 73 Index 75 Picture Credits 79 About the Author 80 MacFarlane_FamilyGuy_CCC_v4.indd 5 4/1/15 8:12 AM CHAPTER TWO Family Guy: TV’s Most Shocking Show eth MacFarlane spent months drawing images for the pilot at his Skitchen table, fi nally producing an eight-minute version of Fam- ily Guy for network broadcast. After seeing the brief pilot, Fox ex- ecutives green-lighted the series. Says Sandy Grushow, president of 20th Century Fox Television, “Th at the network ordered a series off of eight minutes of fi lm is just testimony to how powerful those eight minutes were. Th ere are very few people in their early 20’s who have ever created a television series.”20 Family Guy made its debut on network television on January 31, 1999—right after Fox’s telecast of the Super Bowl. Th e show import- ed the Life of Larry and Larry & Steve dynamic of a bumbling dog owner and his pet (renamed Peter Griffi n and Brian, respectively) and expanded the supporting family to include wife, Lois; older sis- ter, Meg; middle child, Chris; and baby, Stewie. Th e audience for the Family Guy debut was recorded at 22 million. Given the size of the audience, Fox believed MacFarlane had produced a hit and off ered him $1 million a year to continue production.