Protected Areas Host Important Remnants of Marine Turtle Nesting Stocks in the Dominican Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Studies in Marine Science Reef Condition and Protection Of

Regional Studies in Marine Science 32 (2019) 100893 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Regional Studies in Marine Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rsma Reef condition and protection of coral diversity and evolutionary history in the marine protected areas of Southeastern Dominican Republic ∗ Camilo Cortés-Useche a,b, , Aarón Israel Muñiz-Castillo a, Johanna Calle-Triviño a,b, Roshni Yathiraj c, Jesús Ernesto Arias-González a a Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del I.P.N., Unidad Mérida B.P. 73 CORDEMEX, C.P. 97310, Mérida, Yucatán, Mexico b Fundación Dominicana de Estudios Marinos FUNDEMAR, Bayahibe, Dominican Republic c ReefWatch Marine Conservation, Bandra West, Mumbai 400050, India article info a b s t r a c t Article history: Changes in structure and function of coral reefs are increasingly significant and few sites in the Received 18 February 2019 Caribbean can tolerate local and global stress factors. Therefore, we assessed coral reef condition Received in revised form 20 September 2019 indicators in reefs within and outside of MPAs in the southeastern Dominican Republic, considering Accepted 15 October 2019 benthic cover as well as the composition, diversity, recruitment, mortality, bleaching, the conservation Available online 18 October 2019 status and evolutionary distinctiveness of coral species. In general, we found that reef condition Keywords: indicators (coral and benthic cover, recruitment, bleaching, and mortality) within the MPAs showed Coral reefs better conditions than in the unprotected area (Boca Chica). Although the comparison between the Caribbean Boca Chica area and the MPAs may present some spatial imbalance, these zones were chosen for Biodiversity the purpose of making a comparison with a previous baseline presented. -

A Review of Reef Restoration and Coral Propagation Using the Threatened Genus Acropora in the Caribbean and Western Atlantic

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE. 88(4):1075–1098. 2012 coRAl Reef pApeR http://dx.doi.org/10.5343/bms.2011.1143 A REVIEW OF REEF RESTORATION AND CORAL PROPAGATION USING THE THREATENED GENUS ACROPORA IN THE CARIBBEAN AND WESTERN ATLANTIC CN Young, SA Schopmeyer, and D Lirman ABSTRACT Coral reef restoration has gained recent popularity in response to the steady decline of corals and the recognition that coral reefs may not be able to recover naturally without human intervention. To synthesize collective knowledge about reef restoration focused particularly on the threatened genus Acropora in the Caribbean and western Atlantic, we conducted a literature review combined with personal communications with restoration practitioners and an online questionnaire to identify the most effective reef restoration methods and the major obstacles hindering restoration success. Most participants (90%) strongly believe that Acropora populations are severely degraded, continue to decline, and may not recover without human intervention. Low-cost methods such as coral gardening and fragment stabilization were ranked as the most effective restoration activities for this genus. High financial costs, the small footprint of restoration activities, and the potential damage to wild populations were identified as major concerns, while increased public awareness and education were ranked as the highest benefits of coral reef restoration. This study highlights the advantages and outlines the concerns associated with coral reef restoration and creates a unique synthesis of coral restoration activities as a complementary management tool to help guide “best-practices” for future restoration efforts throughout the region. Worldwide coral reef degradation has reached a point where local conservation strategies and natural recovery processes alone may be ineffective in preserving and restoring the biodiversity and long-term integrity of coral reefs (Goreau and Hilbertz 2005). -

Mapping Current and Future Priorities

Mapping Current and Future Priorities for Coral Restoration and Adaptation Programs International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) Ad Hoc Committee on Reef Restoration 2019 Interim Report This report was prepared by James Cook University, funded by the Australian Institute for Marine Science on behalf of the ICRI Secretariat nations Australia, Indonesia and Monaco. Suggested Citation: McLeod IM, Newlands M, Hein M, Boström-Einarsson L, Banaszak A, Grimsditch G, Mohammed A, Mead D, Pioch S, Thornton H, Shaver E, Souter D, Staub F. (2019). Mapping Current and Future Priorities for Coral Restoration and Adaptation Programs: International Coral Reef Initiative Ad Hoc Committee on Reef Restoration 2019 Interim Report. 44 pages. Available at icriforum.org Acknowledgements The ICRI ad hoc committee on reef restoration are thanked and acknowledged for their support and collaboration throughout the process as are The International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) Secretariat, Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and TropWATER, James Cook University. The committee held monthly meetings in the second half of 2019 to review the draft methodology for the analysis and subsequently to review the drafts of the report summarising the results. Professor Karen Hussey and several members of the ad hoc committee provided expert peer review. Research support was provided by Melusine Martin and Alysha Wincen. Advisory Committee (ICRI Ad hoc committee on reef restoration) Ahmed Mohamed (UN Environment), Anastazia Banaszak (International Coral Reef Society), -

Unique Resort Experiences

Unique Resort Experiences Mexico Caribbean ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Cancun ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Zoëtry Paraiso de la Bonita Riviera Maya ............................................................................................. 4 Zoëtry Villa Rolandi Isla Mujeres Cancun ............................................................................................. 5 Secrets Playa Mujeres Golf & Spa Resort ............................................................................................. 6 Secrets Riviera Cancun ......................................................................................................................... 6 Secrets The Vine Cancun ...................................................................................................................... 6 Breathless Riviera Cancun Resort & Spa .............................................................................................. 7 Dreams Playa Mujeres Golf & Spa Resort ............................................................................................ 7 Dreams Sands Cancun Resort & Spa .................................................................................................... 8 Riviera Maya ............................................................................................................................................. -

Mapping Ontogenetic Habitat Shifts of Coral Reef Fish at Mona Island, Puerto Rico Cartografía De Las Mudanzas De Habitáculos D

Mapping ontogenetic habitat shifts of coral reef fish at Mona Island, Puerto Rico Item Type conference_item Authors Schärer, M.T.; Nemeth, M.I.; Appeldoorn, R.S. Download date 02/10/2021 07:32:38 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/31272 Mapping Ontogenetic Habitat Shifts of Coral Reef Fish at Mona Island, Puerto Rico MICHELLE T. SCHÄRER, MICHAEL I. NEMETH, and RICHARD S. APPELDOORN Department of Marine Sciences, University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, Puerto Rico 00681 ABSTRACT Coral reef fishes use a variety of habitats throughout daily, ontogenetic, and spawning migrations, therefore requiring a suite of habitats to complete their life cycle. The use of multiple habitats by grunts (Haemulidae) and snappers (Lutjanidae) was investigated at Mona Island, a remote island off western Puerto Rico. The objective of this study was to determine if the distribution of three different life stages was random in relation to benthic habitat types. Coral reef fish were sampled throughout all habitat types randomly over a period of six months. For seven species of grunts and snappers median fork length was significantly different by habitat type identifying critical habitats for juveniles distinct from adult habitats. Within a life stage significant differences were observed in fish density by habitat type. Early juvenile grunts and snappers were more abundant in habitats of depths less than 5 m, mainly in rocky shores and seagrass areas with patches of coral or other hard structures. Larger juveniles were significantly more abundant in depths less than 5m in coral dominated habitats. Adults were abundant throughout the habitats of all depth ranges, except for two species Haemulon chrysargyreum and Lutjanus mahogoni, which were limited to shallower habitats. -

Inside Brochure

INSIDE BROCHURE THE ESTATES CORALES Corales represents a very exclusive community within Become a part of our magnificent paradise community with the purchase of a vacation home in the elite Estates Once at the resort, the opportunities for relaxation and PUNTACANA Resort & Club. It is a warm, private refuge at PUNTACANA Resort & Club. Grupo PUNTACANA has recreation are endless. You can test your skills at our world where neighbors know neighbors and children make worked meticulously to develop communities in harmony class golf courses, give yourself over to a master lifelong friends. To see that Corales is truly a special place with their lush surroundings, preserving the rare natural therapist at Six Senses Spa, or walk along five miles of to make your vacation home, you need only look at whom treasures of the Dominican Republic. pristine, white beaches. We feature a pioneering ecological you’d be living next to: Oscar de la Renta, Julio Iglesias, park with SEGWAY tours, a full-service marina, scuba tours and Mikhail Baryshnikov all own homes in Corales. Come join the ranks of Oscar de la Renta and Julio to sunken ships, exceptional dining options, and numerous Corales is home to one of the globe’s top golf courses, Iglesias, stepping into an exclusive lifestyle of relaxation, designed by world-famous architect Tom Fazio. Set between excitement, and understated elegance. With homes along water sports, along with house staff and nanny services for rocky cliffs and coral reefs, this distinctive course offers our scrupulously manicured golf course and the sparkling your convenience. picturesque ocean views and exciting challenges sure to Caribbean Sea, there’s an abundance of locations and satisfy any golf fanatic. -

Dreams Dominicus La Romana Last Updated August 9, 2021

CONTACT INFORMATION ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 PROPERTY OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 TOTAL ROOM COUNT: 488 ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 UNIQUE SELLING POINTS ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 UNLIMITED-LUXURY® INCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 PAYMENT METHODS ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Coral Reef Decline and Beach Erosion in the Dominican Republic………….………

Working Paper _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Coastal Capital: Dominican Republic Case studies on the economic value of coastal ecosystems in the Dominican Republic JEFFREY WIELGUS, EMILY COOPER, RUBEN TORRES, and LAURETTA BURKE Suggested Citation: Wielgus, J., E. Cooper, R. Torres and L. Burke. 2010. Coastal Capital: Dominican Republic. Case studies on the economic value of coastal ecosystems in the Dominican Republic. Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at http://www.wri.org/ coastal-capital. Photos: José Alejandro Alvarez World Resources Institute 10 G Street, NE Washington, DC 20002 Tel: 202-729-7600 www.wri.org April 2010 World Resources Institute Working Papers contain preliminary research, analysis, findings, and recommendations. They are circulated to stimulate timely discussion and critical feedback and to influence ongoing debate on emerging issues. Most working papers are eventually published in another form and their content may be revised. Project Partners The Coastal Capital project in the Dominican Republic was implemented in collaboration with Reef Check-Dominican Republic. This project would not have been possible without the financial support of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Swedish International Biodiversity Programme (SwedBio). i Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………………… iii Executive Summary…..……………………………………………………………..……………..... iv 1. Coralline beaches in the Dominican Republic: Two studies…………………………………. 1 a. Potential economic impacts of beach erosion in the Dominican Republic…………. 2 b. Coral reef decline and beach erosion in the Dominican Republic………….………. 7 2. A worrying trend: Declines in coral reef- and mangrove-associated fisheries in the Dominican Republic ………………………………………………………………………. 12 3. Dive tourism in La Caleta Marine Park: A win-win opportunity for fish and fishermen ………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Pearly-Eyed Thrasher) Wayne J

Urban Naturalist No. 23 2019 Colonization of Hispaniola by Margarops fuscatus Vieillot (Pearly-eyed Thrasher) Wayne J. Arendt, María M. Paulino, Luis R. Pau- lino, Marvin A. Tórrez, and Oksana P. Lane The Urban Naturalist . ♦ A peer-reviewed and edited interdisciplinary natural history science journal with a global focus on urban areas ( ISSN 2328-8965 [online]). ♦ Featuring research articles, notes, and research summaries on terrestrial, fresh-water, and marine organisms, and their habitats. The journal's versatility also extends to pub- lishing symposium proceedings or other collections of related papers as special issues. ♦ Focusing on field ecology, biology, behavior, biogeography, taxonomy, evolution, anatomy, physiology, geology, and related fields. Manuscripts on genetics, molecular biology, anthropology, etc., are welcome, especially if they provide natural history in- sights that are of interest to field scientists. ♦ Offers authors the option of publishing large maps, data tables, audio and video clips, and even powerpoint presentations as online supplemental files. ♦ Proposals for Special Issues are welcome. ♦ Arrangements for indexing through a wide range of services, including Web of Knowledge (includes Web of Science, Current Contents Connect, Biological Ab- stracts, BIOSIS Citation Index, BIOSIS Previews, CAB Abstracts), PROQUEST, SCOPUS, BIOBASE, EMBiology, Current Awareness in Biological Sciences (CABS), EBSCOHost, VINITI (All-Russian Institute of Scientific and Technical Information), FFAB (Fish, Fisheries, and Aquatic Biodiversity Worldwide), WOW (Waters and Oceans Worldwide), and Zoological Record, are being pursued. ♦ The journal staff is pleased to discuss ideas for manuscripts and to assist during all stages of manuscript preparation. The journal has a mandatory page charge to help defray a portion of the costs of publishing the manuscript. -

C:\Documents and Settings\David Carlson\Desktop\SHA97

1997 SHA Conference on Historical and Underwater SOCIETY FOR HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY Archaeology Corpus Christi, TX 1997 AWARDS OF MERIT January 8 - 12, 1997 to be presented to PILAR LUNA ERREGUERENA Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, Mexico Seaports, Ships, and Central Places TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Abstracts TEXAS ARCHEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 1997 J.C. HARRINGTON MEDAL JAMES DEETZ University of Virginia Hosted by Texas A&M University Institute of Nautical Archaeology Ships of Discovery ABSTRACTS 1997 CONFERENCE STAFF Conference Chair and Program Coordinator............. David L. Carlson Terrestrial Program Chair .......................Shawn Bonath Carlson Underwater Program Chair ............................. Denise Lakey Registration Chair .............................. Frederick M. Hocker Society for Historical Archaeology Local Arrangements Chair............................... Toni Carrell Volunteer Coordinator.................................Becky Jobling Tours Coordinator .....................................Mary Caruso 30th Conference on Historical and Book Room Coordinator .......................... Lawrence E. Babits Underwater Archaeology Employment Coordinator............................... Sarah Mascia Conference Coordinator................................. Tim Riordan Hosted by: Texas A&M University Institute of Nautical Archaeology Ships of Discovery January 8-12, 1997 Omni Bayfront Hotel Corpus Christi, Texas With financial support provided by: Corpus Christi Omni Bayfront Hotel Corpus Christi Area Convention & -

8. Coastal Fisheries of the Dominican Republic

175 8. Coastal fisheries of the Dominican Republic Alejandro Herrera*, Liliana Betancourt, Miguel Silva, Patricia Lamelas and Alba Melo Herrera, A., Betancourt, L., Silva, M., Lamelas, P. and Melo, A. 2011. Coastal fisheries of the Dominican Republic. In S. Salas, R. Chuenpagdee, A. Charles and J.C. Seijo (eds). Coastal fisheries of Latin America and the Caribbean. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper. No. 544. Rome, FAO. pp. 175–217. 1. Introduction 176 2. Description of fisheries and fishing activities 178 2.1 Description of fisheries 178 2.2 Fishing activity 188 3. Fishers and socio-economic aspects 191 3.1 Fishers’ characteristics 191 3.2 Social and economic aspects 193 4. Community organization and interactions with other sectors 194 4.1 Community organization 194 4.2 Fishers’ interactions with other sectors 195 5. Assessment of fisheries 197 6. Fishery management and planning 199 7. Research and education 201 7.1. Fishing statistics 201 7.2. Biological and ecological fishing research 202 7.3 Fishery socio-economic research 205 7.4 Fishery environmental education 206 8. Issues and challenges 206 8.1 Institutionalism 207 8.2 Fishery sector plans and policies 207 8.3 Diffusion and fishery legislation 208 8.4 Fishery statistics 208 8.5 Establishment of INDOPESCA 208 8.6 Conventions/agreements and organizations/institutions 209 References 209 * Contact information: Programa EcoMar, Inc. Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. E-mail: [email protected] 176 Coastal fisheries of Latin America and the Caribbean 1. INTRODUCTION In the Dominican Republic, fishing has traditionally been considered a marginal activity that complements other sources of income. -

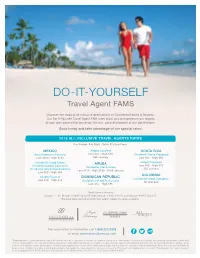

DO-IT-YOURSELF Travel Agent FAMS

DO-IT-YOURSELF Travel Agent FAMS Discover the tropical all-inclusive destinations of Occidental Hotels & Resorts. Our Do-It-Yourself Travel Agent FAM rates allow you to experience our resorts at your own pace while you enjoy the sun, sand and beauty of our destinations. Book today and take advantage of our special rates! 2015 ALL-INCLUSIVE TRAVEL AGENTS RATES Per Person, Per Night Rates Starting From: MEXICO Allegro Cozumel COSTA RICA Royal Hideaway Playacar Low $48 - High $70 Occidental Grand Papagayo Low $150 - High $175 $60 January Low $65 - High $85 Occidental Grand Xcaret, ARUBA Allegro Papagayo Occidental Grand Cozumel & Low $48 - High $75 Occidental Grand Aruba Occidental Grand Nuevo Vallarta $65 January Low $125 - High $185 - $165 January Low $55 - High $85 COLOMBIA Allegro Playacar DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Occidental Grand Cartagena Low $48 - High $75 Occidental Grand Punta Cana All Year $80 Low $55 - High $85 Travel Dates & Seasons: January: 1 – 31; All year: 1/10/15-12/22/15; High Season: 1/3/15-3/31/15; Low Season: 4/1/15-12/22/15. Blackout dates and other restrictions apply*. Subject to space available. For reservation & information call 1.888.223.3308 or email [email protected] *Requirements: 2 night minimum stay (if booked more than 7 days prior to arrival) or 3 night minimum (if booked within 7 days prior to arrival). Above travel agent rates, applicable only to travel agent room, are all-inclusive, per person, per night and based on double occupancy in the lead room category and may vary by resort/destination. Single, extra person and children’s rates are available.