Worthington Ferries in the Firt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Place-Names in This Book Were Collected As Part of The

Introduction The place-names in this book were collected as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Board-funded (AHRB) ‘Norse-Gaelic Frontier Project, which ran from autumn 2000 to summer 2001, the full details of which will be published as Crawford and Taylor (forthcoming). Its main aim was to explore the toponymy of the drainage basin of the River Beauly, especially Strathglass,1 with a view to establishing the nature and extent of Norse place-name survival along what had been a Norse-Gaelic frontier in the 11th century. While names of Norse origin formed the ultimate focus of the Project, much wider place-name collection and analysis had to be undertaken, since it is impossible to study one stratum of the toponymy of an area without studying the totality. The following list of approximately 500 names, mostly with full analysis and early forms, many of which were collected from unpublished documents, has been printed out from the Scottish Place-Name Database, for more details of which see Appendix below. It makes no claims to being comprehensive, but it is hoped that it will serve as the basis for a more complete place-name survey of an area which has hitherto received little serious attention from place-name scholars. Parishes The parishes covered are those of Kilmorack KLO, Kiltarlity & Convinth KCV, and Kirkhill KIH (approximately 240, 185 and 80 names respectively), all in the pre-1975 county of Inverness-shire. The boundaries of Kilmorack parish, in the medieval diocese of Ross, first referred to in the medieval record as Altyre, have changed relatively little over the centuries. -

Arrie, North Kessock

Highland Archaeology Services Ltd Bringing the Past and Future Together Arrie, North Kessock Archaeological Watching Brief 7 Duke Street Cromarty Ross-shire IV11 8YH Tel / Fax: 01381 600491 Mobile: 07834 693378 Email: [email protected] Web: www.hi-arch.co.uk Registered in Scotland no. 262144 Registered Office: 10 Knockbreck Street, Tain, Ross-shire IV19 1BJ VAT No. GB 838 7358 80 Arrie North Kessock Archaeological Watching Brief December 2015 Arrie, North Kessock Archaeological Watching Brief Report No. HAS160201 Site Code HAS_ANK15 Client Graeme Stewart Planning Ref 14/02009/FUL OS Grid Ref NH 6797 5133 Date/ revision 01/02/2015 Author Lynne McKeggie Summary An archaeological watching brief was undertaken following a walkover survey and trial trenching in order to identify and record archaeological features within the development area of a new house. 19 features were found, of which 13 are considered to be archaeological. These include a field drain, 5 pits, 6 post-holes and a shallow ditch. One saddle quern was recovered but no other artefacts. All features were excavated by hand and recorded. No further work is recommended for this site. Acknowledgements and Copyright The fieldwork was undertaken by Pete Higgins. The report was written by Lynne McKeggie, including material from Pete Higgins and Lachlan McKeggie, and edited and formatted by John Wood. Background mapping has been reproduced by permission of the Ordnance Survey under Licence 100043217. Historic maps are courtesy of the National Library of Scotland. The report’s author(s) and Highland Archaeology Services Ltd jointly retain copyright in all reports produced but will allow the client and other recipients to make the report available for reference and research (but not commercial) purposes, either on paper, or electronically, without additional charge, provided this copyright is acknowledged. -

Rosehall Information

USEFUL TELEPHONE NUMBERS Rosehall Information POLICE Emergency = 999 Non-emergency NHS 24 = 111 No 21 January 2021 DOCTORS Dr Aline Marshall and Dr Scott Smith PLEASE BE AWARE THAT, DUE TO COVID-RELATED RESTRICTIONS Health Centre, Lairg: tel 01549 402 007 ALL TIMES LISTED SHOULD BE CHECKED Drs C & J Mair and Dr S Carbarns This Information Sheet is produced for the benefit of all residents of Creich Surgery, Bonar Bridge: tel 01863 766 379 Rosehall and to welcome newcomers into our community DENTISTS K Baxendale / Geddes: 01848 621613 / 633019 Kirsty Ramsey, Dornoch: 01862 810267; Dental Laboratory, Dornoch: 01862 810667 We have a Village email distribution so that everyone knows what is happening – Golspie Dental Practice: 01408 633 019; Sutherland Dental Service, Lairg: 402 543 if you would like to be included please email: Julie Stevens at [email protected] tel: 07927 670 773 or Main Street, Lairg: PHARMACIES 402 374 (freephone: 0500 970 132) Carol Gilmour at [email protected] tel: 01549 441 374 Dornoch Road, Bonar Bridge: 01863 760 011 Everything goes out under “blind” copy for privacy HOSPITALS / Raigmore, Inverness: 01463 704 000; visit 2.30-4.30; 6.30-8.30pm There is a local residents’ telephone directory which is available from NURSING HOMES Lawson Memorial, Golspie: 01408 633 157 & RESIDENTIAL Wick (Caithness General): 01955 605 050 the Bradbury Centre or the Post Office in Bonar Bridge. Cambusavie Wing, Golspie: 01408 633 182; Migdale, Bonar Bridge: 01863 766 211 All local events and information can be found in the -

A Guide for Families Living with Dementia in West Highland

A guide for families living with dementia in West Highland Supported by Argyll & Bute Council, The Highland Council and NHS Highland Compiled May 2012 2 Welcome and how to use this guide This guide has been produced as a result of many discussions with families and staff who are supporting someone with dementia in the NHS Highland area. The guide is broken into three sections: • Section 1 Issues and things to think about. This section provides an overview of important issues and identifies where to find out further information. • Section 2 Who’s who and what’s their role. This outlines the main staff and agencies likely to be involved in supporting the person with dementia and their key roles. • Section 3 Local and national supports and services. This section provides contact details for advice, information and support in your area for you and the person with dementia. We hope you find this guide a real help to you and your family in living with dementia. Signatories: Henry Simmons – Chief Executive, Alzheimer Scotland Elaine Mead - Chief Executive, NHS Highland Cleland Sneddon - Executive Director, Community Services, Argyll & Bute Council Bill Alexander - Director of Health & Social Care, Highland Council 3 Acknowledgements We are indebted to all the family members who took part in the research for giving their time, suggestions and commitment, which has provided the foundation of the content, design and style of the guide. The guide has drawn on a number of resources. In particular we would like to thank NHS Health Scotland (www.healthscotland.com) for their permission to refer to the following publications: • Facing dementia – how to live well with your diagnosis • Coping with dementia – a practical handbook for carers Single copies of the above booklets and their accompanying DVDs are available to people with dementia, their partners, families and friends from the Dementia Helpline on 0808 808 3000. -

Rod Kinnermony Bends

Document: Form 113 Issue: 1 Record of Determination Related to: All Contracts Page No. 1 of 64 A9 Kessock Bridge 5 year Maintenance Programme Record of Determination Name Organisation Signature Date Redacted Redacted 08/03/2018 Prepared By BEAR Scotland 08/08/2018 Redacted 03/09/2018 Checked By Jacobs Redacted 10/09/2018 Client: Transport Scotland Distribution Organisation Contact Copies BEAR Scotland Redacted 2 Transport Scotland Redacted 1 BEAR Scotland Limited experience that delivers Transport Scotland Trunk Road and Bus Operations Document: EC DIRECTIVE 97/11 (as amended) ROADS (SCOTLAND) ACT 1984 (as amended) RECORD OF DETERMINATION Name of Project: Location: A9 Kessock Bridge 5 year Maintenance A9 Kessock Bridge, Inverness Programme Marine Licence Application Structures: A9 Kessock Bridge Description of Project: BEAR Scotland are applying for a marine licence to cover a 5-year programme of maintenance works on the A9 Kessock Bridge, Inverness. The maintenance activities are broken down into ‘scheme’ and ‘cyclic maintenance’. ‘Scheme’ represents those works that will be required over the next 5 years, whilst ‘cyclic maintenance’ represents those works which may be required over the same timeframe. Inspections will also be carried out to identify the degree of maintenance activity required. Following review of detailed bathymetric data obtained in August 2018, BEAR Scotland now anticipate that scour repairs at Kessock Bridge are unlikely to be required within the next 5 five years; hence, this activity is considered cyclic maintenance. The activities encompass the following: Schemes • Fender replacement; • Superstructure painting and • Cable stay painting. Cyclic maintenance • Scour repairs; • Drainage cleaning; • Bird guano removal; • Structural bolt and weld renewal; • Mass damper re-tuning; • Pendel bearing inspection; • Cleaning and pressure washing superstructure • Cable stay re-tensioning; • Minor bridge maintenance. -

Timetable Updated 28Th June 2021

Timetable updated 28th June 2021 Days of Operation Monday to Friday Days of Operation Saturdays Service Number 62 Service Number 62 Service Description Tain - Lairg - Golspie - Hemsldale Service Description Tain - Lairg Service No. 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 62 Service No. 62 62 62 62 62 Sch Sch #Sch Sch NF Sch F #Sch Tain Asda - 1003 1303 1540 - Tain Asda - - - - 1005 1305 - - 1630 - Codes: Tain Lamington Street 0800 1010 1310 1545 1830 Tain Lamington Street 0645 0701 0708 0713 1012 1312 - - 1635 1830 NF Not Fridays Edderton Bus Shelter 0810 1020 1320 1555 1840 Edderton Bus Shelter 0655 0711 0718 0723 1022 1322 - - 1645 1840 Sch Schooldays only Ardgay Community Hall 0822 1033 1332 1607 1852 Ardgay Community Hall 0707 0723 0730 0735 1035 1335 - - 1657 1852 #Sch School holidays only Migdale Hospital - - R1335 - R1853 Migdale Hospital - - - - - 1338 - - - 1855 F Fridays only Bonar Bridge Post Office 0825 1036 1336 1610 1855 Bonar Bridge Post Office 0710 0726 0733 0738 1038 1343 - - 1700 1900 Invershin 0830 1041 1341 1615 1900 Invershin 0715 0731 0738 0743 1043 1348 - - 1705 1905 Inveran Bridge - 1043 1343 1617 - Inveran Bridge - - - - 1045 1350 - - - - Achany Road End - - 1350 - - Achany Road End - - - - - 1357 - - - - Lairg Post Office 0842 1055 1357 1629 1914 Lairg Costcutter - - - 0753 - - - - - - Lairg Post Office 0727 0743 0750 0755 1057 1404 - - 1717 1917 Codes: R Operates via Migdale Hospital on request. If operates via Link Link Link Migdale bus will call at subsequent timing points up to four Lairg Post Office - - 0800 0758 1100 -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

Inverness Burgh Directory

m. M •^.^nr> ..«/ 'V.y 1. Vv y XHK &Feat Scoteh Wineey Manufactured exjaressly for JOHN FORBKS, Itiverness, in New Stripes and Checks, also in White and all Colours, IS the: idkal. fabric for Ladies' Blouses, Children's Dresses, Gent's Shirts and Pyjamas, and every kind of Day, Night and Underwear, ENDLESS IN WEAR AND POSITIVELY UNSHRINKABLE. 31 inches wide, 1/9 per yard. New Exclusive Weaves. All Fast Colours. Pattern Bunches Free on application to JOHN FORBES Hig^li Street Sc Ingrlis Street INVERNESS. "ESTATE DUTIES.'* Distinctive System OF Assurance. I4OW Premiums. Lo^v Expenses. SCOTTISH PROVIDENT INSXmJTION. AccuHinlated^iFunds jeiceecl £13,750,000. Aberdeen Branch : 166 UNION STREET Inspector of Agencies (Northern District :) WILLIAM FARQUHARSON. rJAMES D. MACKIE. Local Secretaries j^j^^^j^j) TENNANT. AGENTS IN INVERNESS; Messrs ANDERSON & SHAW, W.S, Messrs JAMES ROSS & BOYD, Solicitors, DAVID ROSS, Solicitor, 63 Church Street, Head Office—No. 6 St. ANDREW SQUARE, EDINBURGH : ® Dortaem $ls$urancc ConqKini^ l2ead Offices flbeMeen S London FIRE. LIFE. ACCIDENT. Accumulated Funds, £6,782,900 FIRK BRAKCH Large Keserves, Prompt and equitable settlement of Losses. Surveys made and rates quoted free of charge. I^IFK BRAKCH The "with profits" section has many features attractive to Assurants, Amongst these are THE STRONG RESERVES.—Very stringent Eeserves, on a 2| per cent, basis, have been set aside. THE LOW EXPENSES.—The expenditure is restricted to 10 per cent, of the premiums. ALL PROFITS TO ASSURED.— Policy-holders receive the entire profits. They thus obtain the advantages of a Mutual Society, and in addition the further security afforded by a Proprietary Ofiice. -

Wester Rarichie Hill, Tain, Ross-Shire

Wester Rarichie Hill, Tain, Ross-shire Wester Rarichie Hill The contiguous, picturesque Seaboard Villages of Tain, Ross-shire Hilton, Balintore and Shandwick to the northeast of Wester Rarichie Hill feature a pier, harbour A rare opportunity to purchase a block of and bay. Balintore offers a shop, post office and hill ground overlooking the moray firth. pharmacy. The closest town of Tain, Scotland’s oldest burgh, provides further services. The hill (currently forming part of a larger Tain 8 miles, Inverness 34 miles, agricultural holding, Wester Rarichie Farm) is Inverness Airport 41 miles, Edinburgh 188 miles accessed via a private track from a minor road Wester Rarichie Hill (About 726 acres) connecting the Seaboard Villages to the B9175. • Enclosed hill ground varying between 80 The A9 provides transport links north and south, and 200 metres above sea level. and allows easy access to Inverness, the capital of the Highlands. Inverness airport provides regular • Cattle shelter of modern construction. flights throughout the UK and to Europe. The local • Potential for afforestation on the hill, subject railway station at Fearn provides services along to Forestry Commission consent. the ‘Far North Line’. A sleeper service operates from Inverness railway station to London. • Spectacular 360-degree views. • Expansive coastline measuring The Land approximately 1,600 metres. Wester Rarichie Hill extends to approximately 726 acres of land, including a modern farm building. • No recent sporting records but scope for rough shooting and roe deer stalking. The highest summit within the subjects peaks at 200 metres above sea level and offers a About 726 acres (294 ha) in total. -

Inverness Guide

Ida J890 16 H4 The Official Publication of the Corporation. DA ATO.Ib H4 JE FURNITURE. yp- a3 1 188007184159b ™ Visitors to Scotland should not tail to visit . ANTIQUE A. FRASER & Co.'s SALOONS, (railway station) INVERNESS. Antique Furniture. The Collection Old China. shown in the extensive Old Silver. Galleries and Old Prints Special and Showrooms will Engr GUELPH be found to Hoi UNIVERSITY OF be one of the Highl, largest in the Jac Provinces. Int< The Library OA <3 9 16 H4 PLAIN FIGURES. HdALTH kESUHTS ASSOC! AT IoNi LONDON* ) CURIOSITY SHOP, A. I NVtNNESS. IVERNESS. ' ROYAL HOTEL, INVERNESS. (OPPOSITE RAILWAY STATION.) First class. Highly Recommended. Moderate Charges. Headquarters of the Scottish Automobile Club Dining Room open to Non- Residents. Hotel Porters await all trains and Caledonian Canal Steamers. A Chaiming House, contaii Unique Ccllect.cn of Ant.que Furniture. China and Engrav.ncs.' Under the personal management of the proprietor— Telephone 54. J. S CHRISTIE. i - MITCHELL & CRAIG, The Leading Grocers & Italian Warehousemen, INVERNESS, SUPERB QUALITY - LOW PRICES COMBINED MAINTAINED. WITH HIGH QUALITY. TEAS« Delicate and Refined Flavours, from 1/6 to 2/4 per pound- RflTTPD Weekly importations. Nothing Sweeter or Fresher can possibly be oU I 1 C,K. obtained. Our Stranraer Fresh Butter is a table delicacy. rrwrnAi /^nArrniCC A. car<fu'ly selected stock to choose from. Every Clfc,INfc,KAL UHULCKltO. t hi n g Fresh and in Season. e 10 ' c arce stoc ks of the Choicest \»7I'M¥?Q. ^ ^ ' ' Wines. Port, Sherry, Claret, WliNEr-O. Burgundy, Champagne. WHKKY °ur " ROYAL CREAM OF BEN-WYVIS" has a wortd-wide repu- WrllOlYI. -

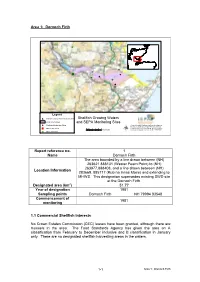

Area 1: Dornoch Firth Shellfish Growing Waters and SEPA Monitoring Sites Report Reference No. 1 Name Dornoch Firth Location

Area 1: Dornoch Firth ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_ ^_^_ ! ^_ # ^_ # ^_ ^_ Legend # Shellfish Growing Waters Monitoring Sites Shellfish Growing Waters Shellfish Growing Waters and SEPA Monitoring Sites ! Shellfish Production Sites (c) 2004 Scottish Environment Protection Agency. Includes material based upon Ordnance Survey " Marine Fish Farms 00.51 2 3 4 5 mapping with permission of H.M. Stationery Office. Kilometers (c) Crown Copyright. Licence number 100020538. ^_ Major Discharges µ Report reference no. 1 Name Dornoch Firth The area bounded by a line drawn between (NH) 263621 888131 (Wester Fearn Point) to (NH) 263977,888408, and a line drawn between (NH) Location Information 283669, 885717 (Rub na Innse Moire) and extending to MHWS. This designation supersedes existing SWD site at the Dornoch Firth. Designated area (km2) 51.77 Year of designation 1981 Sampling points Dornoch Firth NH 79994 83548 Commencement of 1981 monitoring 1.1 Commercial Shellfish Interests No Crown Estates Commission (CEC) leases have been granted, although there are mussels in the area. The Food Standards Agency has given the area an A classification from February to December inclusive and B classification in January only. There are no designated shellfish harvesting areas in the waters. 1- 1 Area 1: Dornoch Firth 1.2 Bathymetric Information This shellfish water encompasses almost the entire area of the Dornoch Firth. The area is some 22 km long by a maximum of 5.5 km wide. The maximum charted depth (at LAT) is <10 m. Approximately half of the area is <0 m chart depth, ie intertidal area exposed at low tide. -

The Rivers of Scotland: the Beauly and Conon

Scottish Geographical Magazine ISSN: 0036-9225 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsgj19 The rivers of Scotland: The Beauly and Conon Lionel W. Hinxman B.A., F.R.S.E. To cite this article: Lionel W. Hinxman B.A., F.R.S.E. (1907) The rivers of Scotland: The Beauly and Conon, Scottish Geographical Magazine, 23:4, 192-202, DOI: 10.1080/00369220708733740 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00369220708733740 Published online: 27 Feb 2008. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 10 View related articles Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsgj20 Download by: [ECU Libraries] Date: 05 June 2016, At: 10:02 192 SCOTTISH GEOGRAPHICAL MAGAZINE THE RIVERS OF SCOTLAND: THE BEAULY AND CONON. By LIONEL W. HINXMAN, B.A., F.R.S.E. (With Map and Diagrams.) UNLIKE the Spey and other large streams of the north-east coast south of the Moray Firth—rivers of simple type in which the tributaries are throughout distinctly subordinate to the main stream—the Beauly and the Conon are examples of a complex river system, formed of several large streams nearly equal in length and volume, and confluent at a comparatively short distance above the river mouth. This character is most marked in the case of the Beauly, and is indeed apparent in the nomenclature of the river system. The Affric, the Cannich, and the Farrar, streams of almost equal volume, unite to form the river Glass, -which at some indeterminate point in its course between Struy and Eilean Aigas ceases to bear that name and flows to the sea as the Beauly River.1 The apparent redundancy in the name Glen Strath Farrar now given to the valley of the Farrar, may possibly be accounted for when we remember that the Beauly Firth was the JEstuarium Fararum of the early geographers, the estuary of the Varar—that name being evidently applied to the whole of the Farrar-Beauly river.