Phokion P. Kotzageorgis* Nomads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERNATIONAL SUMMER SCHOOL on Direct Application of Geothermal Energy

INTERNATIONAL SUMMER SCHOOL on Direct Application of Geothermal Energy Under the auspice of the Division of Earth Sciences GREEK THERMALISMOS Healing sources - Bath-places - SPA-tourism Zisis Agelidis Geologist Dr. A. U. Th. ABSTRACT the 5th century B.C. there are the common baths, public or private, for the proper This paper which tackles with “Ther- service of all the social classes. The malismo Hellenico” is an approach to the ancient Greeks’ belief, about the baths historical data, from the moment that was differentiated depending on the time hydrotherapy has started because of and the place. Their preferences for Herodotus’ very first observations and having cold or hot baths were not later on proved to be a healing process irrelevant to the time of the season and according to Hippocrates and his school. mainly to the prevailing morality. The cold Some concepts and definitions are to be bath was preferred in the arenas and the provided in order to explain the gymnasiums, the hot in the new public contemporary meaning of “Thermalismos” baths, which were called Valania. It’s both as a social need and as a wishful worth to observe that in the main hot bath hope for human health. Moreover, the there was also the steam - bath or natural and chemical properties of the “pyriatirion”, which caused perspiration. water are being mentioned, once they play According to the tradition, after the steam - a major role in the application of hyd- bath, there was the hot – bath and, usually rotherapy. Last but not least, the hydro- soon after, the cold bath. -

Thessaloniki Perfecture

SKOPIA - BEOGRAD SOFIA BU a MONI TIMIOU PRODROMOU YU Iriniko TO SOFIASOFIA BU Amoudia Kataskinossis Ag. Markos V Karperi Divouni Skotoussa Antigonia Melenikitsio Kato Metohi Hionohori Idomeni 3,5 Metamorfossi Ag. Kiriaki 5 Ano Hristos Milohori Anagenissi 3 8 3,5 5 Kalindria Fiska Kato Hristos3,5 3 Iliofoto 1,5 3,5 Ag. Andonios Nea Tiroloi Inoussa Pontoiraklia 6 5 4 3,5 Ag. Pnevma 3 Himaros V 1 3 Hamilo Evzoni 3,5 8 Lefkonas 5 Plagia 5 Gerakari Spourgitis 7 3 1 Meg. Sterna 3 2,5 2,5 1 Ag. Ioanis 2 0,5 1 Dogani 3,5 Himadio 1 Kala Dendra 3 2 Neo Souli Em. Papas Soultogianeika 3 3,5 4 7 Melissourgio 2 3 Plagia 4,5 Herso 3 Triada 2 Zevgolatio Vamvakia 1,5 4 5 5 4 Pondokerassia 4 3,5 Fanos 2,5 2 Kiladio Kokinia Parohthio 2 SERES 7 6 1,5 Kastro 7 2 2,5 Metala Anastassia Koromilia 4 5,5 3 0,5 Eleftherohori Efkarpia 1 2 4 Mikro Dassos 5 Mihalitsi Kalolivado Metaxohori 1 Mitroussi 4 Provatas 2 Monovrissi 1 4 Dafnoudi Platonia Iliolousto 3 3 Kato Mitroussi 5,5 6,5 Hrisso 2,5 5 5 3,5 Monoklissia 4,5 3 16 6 Ano Kamila Neohori 3 7 10 6,5 Strimoniko 3,5 Anavrito 7 Krinos Pentapoli Ag. Hristoforos N. Pefkodassos 5,5 Terpilos 5 2 12 Valtoudi Plagiohori 2 ZIHNI Stavrohori Xirovrissi 2 3 1 17,5 2,5 3 Latomio 4,5 3,5 2 Dipotamos 4,5 Livadohori N. -

Land Subsidence in the Anthemountas Basin

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Open Access Open Access Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss.,Natural 1, 1213–1256, Hazards 2013 Natural Hazards www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci-discuss.net/1/1213/2013/ and Earth System doi:10.5194/nhessd-1-1213-2013and Earth System NHESSD Sciences Sciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 1, 1213–1256, 2013 Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Natural Hazards and Earth Chemistry Chemistry Land subsidence in System Sciences (NHESS). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in NHESS if available. and Physics and Physics the Anthemountas Discussions basin Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric F. Raspini et al. Advanced interpretationMeasurement of landMeasurement subsidence byTechniques validating Techniques Discussions Open Access Open Access Title Page multi-interferometric SAR data:Biogeosciences the case Biogeosciences Abstract Introduction study of the Anthemountas basin Discussions Conclusions References Open Access (northern Greece) Open Access Climate Climate Tables Figures of the Past of the Past F. Raspini1, C. Loupasakis2, D. Rozos2, and S. Moretti1 Discussions J I Open Access 1Department of Earth Sciences, University of Firenze, Firenze, Italy Open Access Earth System J I 2 Earth System Laboratory of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology, Department of GeologicalDynamics Sciences, School of Mining and MetallurgicalDynamics Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Back Close Discussions Athens, Greece Full Screen / Esc Open Access Received: 12 February 2013 – Accepted:Geoscientific 22 March 2013 – Published: 11Geoscientific April 2013 Open Access Instrumentation Instrumentation Correspondence to: F. -

Public Relations Department [email protected] Tel

Public Relations Department [email protected] Tel.: 210 6505600 fax : 210 6505934 Cholargos, Wednesday, March 6, 2019 PRESS RELEASE Hellenic Cadastre has made the following announcement: The Cadastre Survey enters its final stage. The collection of declarations of ownership starts in other two R.U. Of the country (Magnisia and Sporades of the Region of Thessalia). The collection of declarations of ownership starts on Tuesday, March 12, 2019, in other two regional units throughout the country. Anyone owing real property in the above areas is invited to submit declarations for their real property either at the Cadastral Survey Office in the region where their real property is located or online at the Cadastre website www.ktimatologio.gr The deadline for the submission of declarations for these regions, which begins on March 12 of 2019, is June 12 of 2019 for residents of Greece and September 12 of 2019 for expatriates and the Greek State. Submission of declarations is mandatory. Failure to comply will incur the penalties laid down by law. The areas (pre-Kapodistrias LRAs) where the declarations for real property are collected and the competent offices are shown in detail below: AREAS AND CADASTRAL SURVEY OFFICES FOR COLLECTION OF DECLARATIONS REGION OF THESSALY 1. Regional Unit of Magnisia: A) Municipality of Volos: pre-Kapodistrian LRAs of: AIDINIO, GLAFYRA, MIKROTHIVES, SESKLO B) Municipality of Riga Ferraiou C) Municiplaity of Almyros D) Municipality of South Pelion: pre-Kapodistrian LRAs of: ARGALASTI, LAVKOS, METOCHI, MILINI, PROMYRI, TRIKERI ADDRESS OF COMPETENT CADASTRAL SURVEY OFFICE: Panthesallian stadium of Volos: Building 24, Stadiou Str., Nea Ionia of Magnisia Telephone no: 24210-25288 E-mail: [email protected] Opening hours: Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday from 8:30 AM to 4:30 PM and Wednesday from 8:30 AM to 8:30 PM 2. -

January 24, 2021- Christ's Trial Before Caiaphus, St. Paisios and More

Iconography Adult Spiritual Enrichment January 24, 2021 CLASS 14 ST PAISIOS (JUNE 29 / JULY 12) On 25 July 1924, Arsenios Eznepidis was born in Pharasa (Çamlıca), Cappadocia, shortly before the population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Arsenios' name was given to him by St. Arsenios the Cappadocian, who baptised him, naming the child for himself and foretelling Arsenios' monastic future. After the exchange, the Eznepidis family settled in Konitsa, Epirus. Arsenios grew up there, and after intermediate public school, he learned carpentry. Also, as a child he had great love for Christ and the Panagia, and a great longing to become a monk. He would often leave for the forest in order to study and pray in silence. He took delight in the lives of the Saints, the contests of whom he struggled to imitate with zeal immeasurable and exactness astounding, cultivating in the process humility and love. During the civil war in Greece, Arsenios served as a radio operator (1945-1949). In combat operations, he was distinguished for his bravery, self-sacrifice, and moral righteousness. In 1950, having completed his service, he went to Mount Athos to become a monk: first to Father Kyril, the future abbot of Koutloumousiou monastery, and then to Esphigmenou Monastery (although he was not supportive of their later opposition to the Ecumenical Patriarchate). Arsenios, having been a novice for four years, was tonsured a Rassophore monk on 27 March 1954, and was given the name Averkios. Soon after, Father Averkios went to the idiorrhythmic brotherhood of Philotheou monastery, where his uncle was a monk. -

Hydrogeological Regime and Groundwater Occurence in the Anthemountas River Basin, Northern Greece

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, vol. XLVII 2013 Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, τομ. XLVII , 2013 Proceedings of the 13th International Congress, Chania, Sept. Πρακτικά 13ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Χανιά, Σεπτ. 2013 2013 HYDROGEOLOGICAL REGIME AND GROUNDWATER OCCURENCE IN THE ANTHEMOUNTAS RIVER BASIN, NORTHERN GREECE Kazakis N.1, Voudouris K.1, Vargemezis G.2 and Pavlou A.1 1Laboratory of Engineering Geology & Hydrogeology, Department of Geology, Aristolte University of Thessaloniki, Greece. 2Laboratory of Applied Geophysics Department of Geology Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece. Abstract The Anthemountas river basin is located in northern Greece and covers an area of 374 km2. The mountainous part of the basin consists of ophiolitic, crystalline and carbonate rocks, whereas the lowlands comprise Neogene and Quaternary sedi- ments. Porous aquifers are developed in neogene and quaternary deposits of con- fined and/or unconfined conditions. Karstic aquifers are developed in the carbonate rocks and there are aquifers in the Mesozoic and Palaeozoic fissured rocks. The wa- ter demands of the basin are mainly met by the exploitation of the porous aquifers through a large number of boreholes (more than 1000). The aquifers of fissured rocks discharge through cold springs without significant flow rate. Thermal hot springs are recorded across the Anthemountas fault discharging a mixture of geo- thermal fluids and cold water from the karst aquifer. According to their hydrogeo- logical and lithological characteristics, porous aquifers can be divided into the sub- systems of Galatista and Galarinos in the eastern part of the Anthemountas basin, Vasilika-Risio-Thermi and Tagardes-Trilofos in the western part and Peraia-Agia Triada and AUTh farm-Makedonia airport in the coastal area. -

Ηalkidiki Greece Conference Center Guide Χαλκιδική Οδηγός Συνεδριακών Κέντρων 1 Αegean Melathron

Ηalkidiki Greece Conference Center Guide Χαλκιδική Οδηγός Συνεδριακών Κέντρων 1 Αegean Melathron .............................. 4 Eagles Palace ....................................... 10 Portes Beach Hotel ........................... 16 Conference Center Map Alexandros Palace ................................ 5 Ekies All Senses Resort ................... 11 Portes Palace ....................................... 17 Anthemus Sea ....................................... 6 Istion Club & Spa ............................... 12 Porto Carras Grand Resort ........... 18 F Lake KoroniaLake Volvi rom Egnatia Odos Sholari Stavros Χάρτης ΣυνεδριακώνPefka Κέντρων Peristerona Rendina Aristotle’s Holiday Resort & Spa ....... 7 Kassandra Palace ............................... 13 Possidi Holidays ................................. 19 P.Lagada Ag. Vasilios Loutra N.Apollonias Asvestochori Stivos Apollonia Ano StavroAthenas Pallas Village .......................... 8 Oceania Club ....................................... 14 Sani Resort ............................................ 20 Lagadikia Kalochori GULF Exohi Vasiloudi Nikomidino Platia Nea Apollonia Blue Bay ..................................................... 9 Pallini Beach ......................................... 15 Theoxenia .............................................. 21 THESSALONIKI OF STRYMONIKOS Gerakarou Kokalou Modio Mesopotamo Hortiatis Pilea Ardameri Melisourgos Olympiada Kalamaria Kissos Sarakina Panorama Zagliveri Ag. Haralambos Mesokomi Varvara C. Marmari GULF Peristera Adam Kalamoto Platanochori -

View Our Menu (PDF)

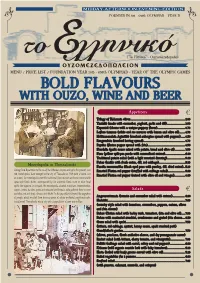

MIDDAY-AFTERNOON-EVENING-EDITION FOUNDED IN 2011 - 698th OLYMPIAD – YEAR D' ("To Elliniko" - Ouzomezedopolio) MENU / PRICE LIST / FOUNDATION YEAR 2015 - 698th OLYMPIAD - YEAR OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES BOLD FLAVOURS WITH OUZO, WINE AND BEER Appetizers € Trilogy of Kalamata olives................................................................................ 2.80 Tzatziki (made with cucumber, yoghurt, garlic and dill)........................... 3.90 Kopanisti (cheese with a unique peppery flavor)......................................... 4.70 Lefkos taramas (white cod roe mousse with lemon and olive oil)......... 4.70 Melitzanosalata Agioritiki (smoked aubergine spread with peppers)....... 4.50 Rengosalata (smoked herring spread)............................................................. 4.70 Paprika (florine pepper spread with feta)....................................................... 4.50 Skordalia (garlic sauce mixed with potato, bread and olive oil)............... 3.90 Fava (yellow split-pea purée with caramelised onions).............................. 6.80 Traditional potato salad (with a light mustard dressing)........................... 5.80 Fakes (lentils with fresh onion, dill, red cabbage)....................................... 5.20 Mezedopolia in Thessaloniki Fasolia mavromatika (black eyed peas with parsley, dill, dried onion)... 5.20 Dating from Byzantium to the era of the Ottoman empire and up to the present, over Roasted Florina red pepper (stuffed with cabbage salad)......................... 5.00 700 ‘mezedopolia’ have emerged in the city of Thessaloniki. Not quite a tavern, nor Roasted Florina red pepper (served with olive oil and vinegar)................ 4.80 an ouzeri, the mezedopolia resemble traditional food markets and serve innumerable tapas-style Greek dishes, accompanied by the authentic Greek ouzo or other local spirits like tsipouro. In the past, the mezedopolia attracted musicians, impressionists, singers, jesters, dandies, poets and educated intellectuals, who gathered there to meet Salads € and relax, eat and drink, discuss and debate. -

State of Play Analyses for Thessaloniki, Greece

State of play analyses for Thessaloniki, Greece Contents Socio-economic characterization of the region ................................................................ 2 Hydrological data .................................................................................................................... 20 Regulatory and institutional framework ......................................................................... 23 Legal framework ...................................................................................................................... 25 Applicable regulations ........................................................................................................... 1 Administrative requirements ................................................................................................ 6 Monitoring and control requirements .................................................................................. 7 Identification of key actors .............................................................................................. 14 Existing situation of wastewater treatment and agriculture .......................................... 23 Characterization of wastewater treatment sector: ................................................................ 23 Characterization of agricultural sector: .................................................................................. 27 Existing related initiatives ................................................................................................ 38 Discussions -

Bod Management Report 201

Management Report of the Board of Directors December 31, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page GENERAL INFORMATION......................................................................................................................... 4 1. CORPORATE AFFAIRS ..................................................................................................................... 7 2. REGULATORY FRAMEWORK ........................................................................................................ 8 3. NEW CONNECTIONS AND ACTIVATIONS OF DELIVERY POINTS ........................................... 8 4. CORPORATE IMAGE & COMMUNICATION .............................................................................. 9 5. DISTRIBUTION NETWORK EXPANSION – CONSTRUCTION ACTIVITIES ................... 10 6. DISTRIBUTION NETWORK OPERATION & MAINTENANCE ........................................... 10 7. NATURAL GAS QUANTITIES ALLOCATION – BILLING - METERING ............................ 11 8. DISTRIBUTION NETWORK ACCESS.......................................................................................... 12 9. IT SYSTEMS....................................................................................................................................... 12 10. HUMAN RESOURCES ..................................................................................................................... 13 11. QUALITY, HEALTH & SAFETY .................................................................................................... 13 12. PROCUREMENT OF MATERIALS, -

Business Plan for the Development of a Self-Storage Facility in the Area of Thessaloniki

Business plan for the development of a Self-Storage facility in the area of Thessaloniki Efstratios Apostolakos SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION & LEGAL STUDIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Executive MBA January 2019 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Efstratios Apostolakos SID: 1101170001 Supervisor: Dr. Stavroula Laspita I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2019 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This paper is my thesis for my master’s degree studies in the Executive MBA course at the International Hellenic University. The main body of this project is a business plan for the development of a self-storage facility in the area of Thessaloniki. Self-storage (a shorthand for "self-service storage") is an industry in which storage space (such as rooms, lockers, containers, and/or outdoor space), also known as "storage units" is rented to tenants, usually on a short-term basis. Self-storage tenants include businesses and individuals. The specific industry exists since the 1960s in USA and is already very mature in most countries of western Europe. In my paper I focus mainly to modern indoor self-storage facilities that provide privately accessible and secured storage units to customers, in most cases with 24/7 access. In Greece at the moment, the specific industry is practically non-existent with only one small business operating in Attica. The business plan concerns the hypothetical case of an existed building that is going to be converted to a Self-Storage warehouse. -

MIXED GRILL for TWO Lamb Chops, Biftéki, Chicken Souvláki

Hours 8am - 10pm Phone: 917.261.4795 Hot Kitchen 10am - 9pm Email: [email protected] thegreektribeca.com . grecanyc.com Greek Market | Casual Dining | at Greca SPECIALTIES MEZES GEMISTÁ GREEK SPREADS Herb Rice Stuffed Tomato & Pepper 23 vegan, gf Tzatziki, Tyrokafteri (Spicy Feta), Hummus with Pepitas Served with Pita Bread 21 (spreads are gluten free) ARTICHOKE MOUSAKÁ Layers of Artichoke, Potato, Cheese, Roasted Leeks & Onions, HERB GUAC & PITA topped with Béchamel 23 vegetarian Smashed Avocados with Garden Herbs 12 (guac is gluten free) SOUVLÁKI over RICE ELIÉS Organic Grilled Chicken Skewers 24 gf Assorted Greek & Sicilian Olives (gf) over Zea Bread 9.5 BIFTÉKI over RICE DOLMADES All Natural Seasoned Beef Patty 24 gf Mini Grape Leaves Rolled with Rice 11 gf, vegan BABY LAMB CHOPS Four Single Cut Lamb Chops with Roasted Potatoes 32 gf LAVRÁKI HOT SOUP Parchment Steam-Baked Whole Greek Bronzino 32 gf Avgolemono 12 | Vegan Greek Lentil 10 (both gf) HOT APPS MIXED GRILL for TWO GÍGANTES Lamb Chops, Biftéki, Chicken Souvláki, Double Baked Giant Beans, non-gmo Tomato 13 vegan, gf Grilled Haloumi, Potatoes, Zucchini, Eggplant, Grilled Whole Scallions GRILLED HALOÚMI 69 (gf) Seared on the Flattop, Sesame Seeds, Greek Honey 12 gf GREEK ‘FRIES’ 2.0 Oven Potatoes, Melted Cheese Blend, Spicy Dip 12 gf KEFTÉDES Grandma’s Meatballs, Tomato Sauce, Feta (6pcs, beef, gf) 15 SALADS OCTAPÓDI HORIÁTIKI Grilled Octopus, Sautéed Onions, Carrots & Cherry Tomatoes 25 gf Kumato Tomatoes, Persian Cucumber, Kalamata Olives, Arugula, Peppers, Scallions,