Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

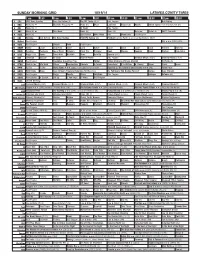

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

2006 NGA Annual Meeting

1 1 NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION 2 OPENING PLENARY SESSION 3 Saturday, August 5, 2006 4 Governor Mike Huckabee, Arkansas--Chairman 5 Governor Janet Napolitano, Arizona--Vice Chair 6 TRANSFORMING THE U.S. HEALTH CARE SYSTEM 7 Guest: 8 The Honorable Tommy C. Thompson, former Secretary, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and former Governor 9 of Wisconsin 10 HEALTHY AMERICA: A VIEW HEALTH FROM THE INDUSTRY 11 Facilitator: 12 Charles Bierbauer, Dean, College of Mass Communications and Information Studies, University of South Carolina 13 Guests: 14 Donald R. Knauss, President, Coca-Cola North America 15 Steven S. Reinemund, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, 16 PepsiCo, Inc. 17 Stephen W. Sanger, Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer, General Mills, Inc. 18 19 DISTINGUISHED SERVICE AWARDS 20 RECOGNITION OF 15-YEAR CORPORATE FELLOW 21 RECOGNITION OF OUTGOING GOVERNORS 22 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE BUSINESS 23 24 REPORTED BY: Roxanne M. Easterwood, RPR 25 A. WILLIAM ROBERTS, JR., & ASSOCIATES (800) 743-DEPO 2 1 APPEARANCE OF GOVERNORS 2 Governor Easley, North Carolina 3 Governor Douglas, Vermont 4 Governor Blanco, Louisiana 5 Governor Riley, Alabama 6 Governor Blunt, Missouri 7 Governor Pawlenty, Minnesota 8 Governor Owens, Colorado 9 Governor Gregoire, Washington 10 Governor Henry, Oklahoma 11 Governor Acevedo Vila, Puerto Rico 12 Governor Turnbull, Virgin Islands 13 Governor Risch, Idaho 14 Governor Schweitzer, Montana 15 Governor Manchin, West Virginia 16 Governor Vilsack, Iowa 17 Governor Fletcher, Kentucky 18 Governor Pataki, New York 19 Governor Lynch, New Hampshire 20 Governor Kaine, Virginia 21 Governor Sanford, South Carolina 22 Governor Romney, Massachusetts 23 Governor Minner, Delaware 24 25 A. -

(Books): Dark Tower (Comics/Graphic

STEPHEN KING BOOKS: 11/22/63: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook 1922: PB American Vampire (Comics 1-5): Apt Pupil: PB Bachman Books: HB, pb Bag of Bones: HB, pb Bare Bones: Conversations on Terror with Stephen King: HB Bazaar of Bad Dreams: HB Billy Summers: HB Black House: HB, pb Blaze: (Richard Bachman) HB, pb, CD Audiobook Blockade Billy: HB, CD Audiobook Body: PB Carrie: HB, pb Cell: HB, PB Charlie the Choo-Choo: HB Christine: HB, pb Colorado Kid: pb, CD Audiobook Creepshow: Cujo: HB, pb Cycle of the Werewolf: PB Danse Macabre: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Half: HB, PB, pb Dark Man (Blue or Red Cover): DARK TOWER (BOOKS): Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger: PB, pb Dark Tower II: The Drawing Of Three: PB, pb Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands: PB, pb Dark Tower IV: Wizard & Glass: PB, PB, pb Dark Tower V: The Wolves Of Calla: HB, pb Dark Tower VI: Song Of Susannah: HB, PB, pb, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Tower VII: The Dark Tower: HB, PB, CD Audiobook Dark Tower: The Wind Through The Keyhole: HB, PB DARK TOWER (COMICS/GRAPHIC NOVELS): Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1-7 of 7 Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born ‘2nd Printing Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Long Road Home: Graphic Novel HB (x2) & Comics 1-5 of 5 Dark Tower: Treachery: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1–6 of 6 Dark Tower: Treachery: ‘Midnight Opening Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Fall of Gilead: Graphic Novel HB Dark Tower: Battle of Jericho Hill: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 2, 3, 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – The Journey Begins: Comics 2 - 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short -

Minutes Freeport Town Council Meeting #01-15 Freeport Town Hall Council Chambers Tuesday, January 6, 2015 – 6:30 P.M

MINUTES FREEPORT TOWN COUNCIL MEETING #01-15 FREEPORT TOWN HALL COUNCIL CHAMBERS TUESDAY, JANUARY 6, 2015 – 6:30 P.M. PRESENT ABSENT EXCUSED James Hendricks, 21 West Street x Kristina Egan, 5 Weston Point Road x Melanie Sachs, 84 Kelsey Ridge Road x Andrew Wellen, 83 Hunter Road x Scott Gleeson, 23 Park Street (will be late) Sarah Tracy, 75 Lower Flying Point Road x William Rixon, 66 Varney Road x Chair Sachs called the meeting to order at 6:34 p.m. and took the roll. She advised that Vice Chair Gleeson would be arriving later. FIRST ORDER OF BUSINESS: Pledge of Allegiance Everyone stood and recited the Pledge. SECOND ORDER OF BUSINESS: To waive the reading of the Minutes of Meeting #24-14 held on December 16, 2014 and to accept the Minutes as printed. MOVED AND SECONDED: To waive the reading of the Minutes of Meeting #24-14 held on December 16, 2014 and to accept the Minutes as printed. (Egan & Tracy) VOTE: (6 Ayes) (1 Excused-Gleeson) THIRD ORDER OF BUSINESS: Announcements (15 minutes) Chair Sachs announced: Winter sand is available for residents’ personal use -Each residential dwelling is eligible for up to 10 gallons of sand per storm. No stock piling is allowed. Any resident assisting a fellow resident with sanding must provide the public works department with written confirmation prior to taking additional materials. Taking of pure rock salt is prohibited without approval from the public works Superintendent. The use of municipal sand for the sanding of private roads is prohibited. All Dog Owners please remember that dogs six months and older are required to be licensed by law. -

Famous Bear Death Raises Larger Questions

July 8 - 21, 2016 Volume 7 // Issue #14 New West: Famous bear death raises larger questions Bullock, Gianforte debate in Big Sky A glimpse into the 2016 fire season Paddleboarding then and now Inside Yellowstone Caldera Plus: Guide to mountain biking Big Sky #explorebigsky explorebigsky explorebigsky @explorebigsky ON THE COVER: Famous grizzly 399 forages for biscuitroot on June 6 in a meadow along Pilgrim Creek as her cub, known as Snowy, peeks out from the safety of her side. Less than two weeks later this precocious cub was hit and killed by a car in Grand Teton National Park. PHOTO BY THOMAS D. MANGELSEN July 8-21, 2016 Volume 7, Issue No. 14 Owned and published in Big Sky, Montana TABLE OF CONTENTS PUBLISHER Eric Ladd Section 1: News New West: EDITORIAL Famous bear death EDITOR / EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MEDIA Opinion.............................................................................5 Joseph T. O’Connor raises larger questions Local.................................................................................6 SENIOR EDITOR/ DISTRIBUTION DIRECTOR Regional.........................................................................12 Tyler Allen Montana.........................................................................16 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Amanda Eggert Section 2: Environment, Sports, & Health CREATIVE SENIOR DESIGNER Taylor-Ann Smith Environment..................................................................17 GRAPHIC DESIGNER Sports.............................................................................21 Carie Birkmeier -

Download File

Monday Morning Report July 2, 2018 INTERNAL The next Executive Committee meeting of the Austin-San Antonio Corridor Council is Wednesday, July 18 at 2:00 pm. This meeting is currently scheduled at the Council offices at 304 C.M. Allen Parkway in San Marcos but local roadwork may cause relocation. We'll let you know. Come by to meet our new chairman John Thomaides, mayor of San Marcos. RSVP to [email protected]. INFRASTRUCTURE Riding a wave of discontent over corruption and the status quo, leftist candidate Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador achieved a landslide victory in yesterday's presidential election in Mexico. He received a broad mandate to re-shape Mexico's government, culture, and society, according to many observers. Details here. Transit-oriented development is transforming cities and suburbs all over the world, but the rush to increase density and tax bases can lead to 'transit-induced gentrification' - that is, current residents priced out by rising prices and taxes. Affordability of housing becomes a growth-limiting obstacle. Arlington County transportation economist Michael Ryan suggests pairing transit development with affordability credits packages under a specific Federal Housing and Urban Development program as a remedy. Story and links here. Related to affordability and transit-oriented development (above), the National Resources Defense Council published a summary earlier this month of how public transportation can actually lead to gentrification and why affordable housing needs to be a part of transit plans. They cite examples from San Francisco, San Diego, Chicago, Atlanta, and other cities. Story. Some interesting details emerged last week with a proposal that the (Austin-area) Central Texas Regional Mobility Authority provide a loan for the relocation of Capital Metro's Kramer Metrorail Station a half-mile north to service the planned Broadmoor redevelopment site. -

Pennywise Dreadful the Journal of Stephen King Studies

1 Pennywise Dreadful The Journal of Stephen King Studies ————————————————————————————————— Issue 1/1 November 2017 2 Editors Alan Gregory Dawn Stobbart Digital Production Editor Rachel Fox Advisory Board Xavier Aldana Reyes Linda Badley Brian Baker Simon Brown Steven Bruhm Regina Hansen Gary Hoppenstand Tony Magistrale Simon Marsden Patrick McAleer Bernice M. Murphy Philip L. Simpson Website: https://pennywisedreadful.wordpress.com/ Twitter: @pennywisedread Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pennywisedread/ 3 Contents Foreword …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 2 “Stephen King and the Illusion of Childhood,” Lauren Christie …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 3 “‘Go then, there are other worlds than these’: A Text-World-Theory Exploration of Intertextuality in Stephen King’s Dark Tower Series,” Lizzie Stewart-Shaw …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 16 “Claustrophobic Hotel Rooms and Intermedial Horror in 1408,” Michail Markodimitrakis …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 31 “Adapting Stephen King: Text, Context and the Case of Cell (2016),” Simon Brown …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 42 Review: “Laura Mee. Devil’s Advocates: The Shining. Leighton Buzzard: Auteur, 2017,” Jill Goad …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 58 Review: “Maura Grady & Tony Magistrale. The Shawshank Experience: Tracking the History of the World's Favourite Movie. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016,” Dawn Stobbart …………………………………………………………………………………………………… p. 59 Review: “The Dark Tower, Dir. Nikolaj Arcel. Columbia Pictures, -

Read the Report/Doctoral Dissertation

i 333 Pursuit of excellence: A phenomenological study of Winning the Award for Excellence Issued by APPA – Leadership in Educational Facilities By Joseph Han Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership, Higher Education Administration in the College of Education Idaho State University Spring 2013 ii © 2013 Joseph K. Han DEDICATION This conversion point of my formal education is dedicated to my parents who gave up the life they knew so that their children would have a chance at a better life. This project is also dedicated to my wife Rhonda and our four children Joshua, Rebecca, Rachel and Sarah for their gracious support on this very long journey. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS With grateful heart, I extend my profound gratitude to Dr. Jonathan Lawson for guidance in and out of the classroom. Our conversations over the past four years have reinforced my academic, professional, and personal confidence. Your philosophy of leadership, pedagogic style, and overall modeling of wisdom will continue to positively impact the lives of departments I lead, colleagues I interact with, and students I teach. I extend a special thanks to all the professors of the Educational Leadership program with extra special thanks to Dr. Alan Frantz and Dr. Jonathan Lawson for the many hours of stimulating conversations in and out of the classroom. I also express my gratitude to the members of my committee for their support and time. I am grateful to Dr. Jonathan Lawson, Dr. Alan Frantz, Dr. Mark Neill, Dr. Karen Appleby and Dr. John Gribas for their guidance on this dissertation. -

84Th Legislative Session TAMUS Cumulative Report

The 84th Legislative Session Cumulative Report The Texas A&M University System August 2015 Table of Contents Overview of the 84th Legislative Session…………………………………………………………………………………………1 Appropriations / Riders………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….21 Bill Facts…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………53 TAMUS Institution-Specific Legislation…………………………………………………………………………………………..55 Overview of Key Higher Education Legislation……………………………………………………………………………….61 Other Bills of Interest…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….87 Bill Analysis Task Force…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..95 State Relations……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….97 Overview of the 84th Legislative Regular Session The 2014 election marked significant changes in statewide leadership positions. With a new Governor and Lieutenant Governor at the helm for the first time in more than a decade, combined with the addition of several newly elected Members, the priorities and process for the 84th Texas Legislature were somewhat unclear at the outset. Governor Greg Abbott and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick assumed their new roles and claimed a strong conservative mandate as a result of their electoral victories. In his first State of the State address, Governor Abbott outlined an agenda built on his campaign proposals, and set forth five “emergency items” – border security, transportation, pre-kindergarten, ethics reform, and higher education research funding. As the Governor’s designated emergency items, they were eligible for consideration earlier in the session. Newly elected Lieutenant Governor Patrick took the reins of the Republican-led Senate, and with the strong backing of the State’s most conservative voters, put forth his major priorities for the 84th Legislative Session. In his inauguration speech, the Lieutenant Governor cited border security, expanded Second Amendment rights, lower property and business taxes, expanded school choice, and reduced costs for higher education among his chief agenda items. -

Paxton Issued His Opinion

KEN PAXTON ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TEXAS January 19, 2016 The Honorable Myra Crownover Opinion No. KP-0057 Chair, Committee on Public Health Texas House of Representatives Re: The legality of fantasy sports leagues Post Office Box 2910 under Texas law (RQ-0071-KP) Austin, Texas 78711-2910 Dear Representative Crownover: You ask for an opinion on two questions involving fantasy sports leagues. 1 Specifically, you ask whether 1. [d]aily fantasy sports leagues such as DraftKings.com and FanDuel.com are permissible under Texas law, and 2. [whether i]t is legal to participate in fantasy sports leagues where the house does not take a "rake" and the participants 0nly wager amongst themselves. Request Letter at 1. I. Factual Background To begin, a brief description of what we understand you to mean by "fantasy sports leagues" is necessary.2 Fantasy sports leagues allow individuals to simulate being a sports team owner or manager. Generally, an individual assembles a team, or lineup, often under a salary limit or budget, comprising actual players from the various teams in the particular sports league, i.e., National Football League, National Basketball League, or National Hockey League. Points are 'See Letter from Honorable Myra Crownover, Chair, House Comm. on Pub. Health, to Honorable Ken Paxton, Tex. Att'y Gen. at 1 (received Nov. 12, 2015), https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/opinion/requests-for opinion-rqs ("Request Letter"). 2The forthcoming description of fantasy sports play is compiled generally from the October 16, 2015, Memorandum from the Nevada Attorney General's Office, to which you refer, concerning the legality of daily fantasy sports. -

House Research Organization • Texas House of Representatives P.O

HOUSE RESEARCH ORGANIZATION • TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES P.O. Box 2910, Austin, Texas 78768-2910 (512) 463-0752 • http://www.hro.house.state.tx.us Steering Committee: Alma Allen, Chairman Dwayne Bohac, Vice Chairman Rafael Anchia Donna Howard Eddie Lucio III Myra Crownover Joe Farias Bryan Hughes Susan King Doug Miller Joe Deshotel John Frullo Ken King J. M. Lozano Joe Pickett HOUSE RESEARCH ORGANIZATION daily floor report Wednesday, April 22, 2015 84th Legislature, Number 55 The House convenes at 10 a.m. Part Two Twenty-five bills are on the daily calendar for second-reading consideration today. The bills analyzed in Part Two of today’s Daily Floor Report are listed on the following page. Alma Allen Chairman 84(R) - 55 HOUSE RESEARCH ORGANIZATION Daily Floor Report Wednesday, April 22, 2015 84th Legislature, Number 55 Part 2 HB 2051 by Crownover Allowing monthly reporting for certain sanitary sewer overflows 47 HB 2050 by Rodriguez Requiring registrars to submit additional voting history information 51 HB 4001 by Raymond Allowing for habilitation services in Medicaid managed care 53 HB 1560 by Hernandez Investment options for money recovered for a minor, incapacitated person 58 HB 1618 by King Extending USF funds to certain entities through 2017 60 HB 2089 by Darby Repealing a $200 additional annual fee for certain occupational licenses 63 HB 2491 by Pickett Licensing and appointment of title insurance escrow officers 66 HB 2825 by Coleman Providing certain authorizations to Texas Indigent Defense Commission 69 HB 2717 by Goldman