Jersey City's Tech Transformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

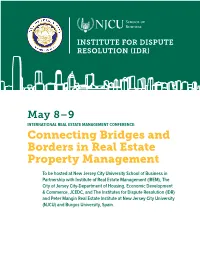

Connecting Bridges and Borders in Real Estate Property Management

INSTITUTE FOR DISPUTE RESOLUTION (IDR) May 8–9 INTERNATIONAL REAL ESTATE MANAGEMENT CONFERENCE: Connecting Bridges and Borders in Real Estate Property Management To be hosted at New Jersey City University School of Business in Partnership with Institute of Real Estate Management (IREM), The City of Jersey City-Department of Housing, Economic Development & Commerce, JCEDC, and The Institutes for Dispute Resolution (IDR) and Peter Mangin Real Estate Institute at New Jersey City University (NJCU) and Burgos University, Spain. INSTITUTE FOR DISPUTE RESOLUTION (IDR) This conference will explore TUESDAY Property Management practices, risk and conflict, & policy trends May 8th affecting investors, owners/ operators, property managers STEWARDSHIP OF PROPERTY MANAGEMENT OPERATIONS and development strategies in FIRST DAY the field of managing commercial 8:30–9:30 a.m. Registration and Breakfast real estate. This event will focus 9:30–9:45 a.m Opening Remarks on cross border common themes PROPERTY MANAGEMENT INSIGHTS Chip Watts, CPM, CCIM, a national IREM leader, will share insights into the critical role of that the commercial real estate property management in the real estate investment process and how IREM supports the property management industry and those who practice in it. property management landscape Introduction | President Sue Henderson, President, New Jersey City University should consider for next Remarks | Tahesha Way, Secretary of State, New Jersey generation sustainability. speaker | Chip Watts, CPM, CCIM, Senior Vice President, IREM Institute of Real Estate Management 10:00–11:30 a.m. Coffee Break 11:30 a.m.–1:00 p.m. BUILDING A PRODUCTIVE PROPERTY MANAGEMENT TEAM IN A MULTIGENERATIONAL WORLD Property management is a people business — and the hallmark of successful management companies is the team of people they pull together. -

Press Release ** Mayor Fulop Invites All Living Jersey City Mayors For

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Kimberly Scalcione November 12, 2019 M: 201-376-0699 E: [email protected] ** Press Release ** Mayor Fulop Invites all Living Jersey City Mayors for Historic Event to Address Census 2020 JERSEY CITY –Mayor Steven Fulop has invited all living former Mayors to City Hall on Wednesday, November 13, 2019 to participate in a historic Census 2020 awareness event. For the first time in the history of Jersey City, the current and former Mayors will join forces to advocate for the upcoming Census 2020 count, addressing the importance of the Census and how it ultimately effects the people, the culture, the infrastructure, and all other critical aspects that make Jersey City the great city it is today. The U.S. constitution mandates the federal government count every resident of the United States every 10 years. It’s estimated that for every resident not accounted for, the city will lose out on $15,000 in federal funding over the next ten years. Mayor Fulop, understanding the importance of the Census and its implications for the next decade, spearheaded this historic event and has kept Jersey City at the forefront as this once-in-a-decade event nears. “The goal is to come together and to show our community how important it is to be fully counted next spring. The Census impacts every aspect of our city and our community – from emergency response, to schools, to our congressional districts,” said Mayor Fulop. “An inaccurate count of Jersey City’s residents in the past has led to unfair and unequal political representation and inequitable access to vital public and private resources. -

Jews, Muslims Partner

Published by the Jewish Community of Louisville, Inc. www.jewishlouisville.org JEWISH LOUISVILLE INSIDE: MAZIN WINNERS Portraits, landscape are top art this year COMMUNITY STORY ON PG 11 FRIDAY Vol. 45, No. 12 | December 20, 2019 | 22 Kislev 5780 Wolk to leave Jews, Muslims partner KI, congregation National interfaith project establishes Louisville council By Lee Chottiner announces By Lee Chottiner Community Editor Community Editor Louisville has become the 11th R a b b i American metro area to establish Michael Wolk a regional presence of the Muslim- will be leaving Jewish Advisory Council (MJAC), Keneseth Israel developing a new platform from Congregation in which to fi ght hate crime and promote 2020. religious minorities. In a letter to The Louisville MJAC was rolled the congregation, out during a Dec. 8 program at which was also Rabbi Michael Wolk the Muhammad Ali Center, which sent to Community, included national leaders of MJAC KI President Joan Simunic announced and its sponsoring organizations: The that Wolk has decided not to accept an American Jewish Committee (AJC) and offer to extend his contract beyond its the Islamic Society of North America. June 30 expiration date. Farooq Kathwari and Stanley “It has been a wonderful opportunity Bergman, co-chairs of the national working with a professional, dedicated, council, spoke at the program. and a passionate person like him,” The Jewish Community Relations Becky Ruby Swansburg and Dr. Muhammad Babar will chair the new Louisville chapter of the Muslim- Simunic wrote. “He has helped guide Jewish Advisory Council. (Community photo by Chris Joyce) Council (JCRC), a major partner in the KI through some challenging times, project, has been working with others Dallas, Kansas City and Los Angeles communities here. -

September 14, 2016 at 6:00 P.M

The action taken by the Municipal Council at the Regular Meeting held on September 14, 2016 at 6:00 p.m. is listed below. The minutes are available for perusal and approval. Unless council advises the City Clerk to the contrary, these minutes will be considered approved by the IMunicipal Council. Robert Byrn^/City Clerk CITY OF JERSEY CITY 280 Grove Street Jersey City, New Jersey 073(12 Robert Byrne, R.M.C., City Clerlt Scan J. Gallagher, R.M.C., Deputy City Clerk Irene G. McNuIty, R.M.C., Deputy City Clerk Rolando R. Lavarro, Jr., Council President Daniel Rivera, Councilperson-at-Large Joyce E. Watterman, Counciiperson-at-Large Frank Gajewsld, Councilperson, Ward A John J. UaHaiuin, III Councilpcrson; Ward B Richard Boggiano, Councilpcrson, Ward C Michael Yun, Councilperson, Ward D Candice Osborne, Councilperson, Ward E Dianc Coleman, Coundlperson, Ward F Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the IMunicipal Council Wednesday, September 14, 2016 at 6:00 p.m. Please Note: The next caucus meeting of Council Is scheduled for Monday, September 26, 2016 at 5:30 p.m. in the Efrain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City Hall. The next regular meeting of Council is scheduled for Wednesday, September 28,2016 at 6:00 p.m. in the Anna and Anthony R. Cucci Memorial Council Chambers, City Hall. A pre-meeting caucus may be held in the Efi'ain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City Hall. REGULAR MEETING STARTED: 6:12 p.m. 1. (a) INVOCATION: (b) ROLL CALL: At 6:12 p.m., all nine (9) members were present. -

Agenda Regular Meeting of the Municipal Council Wednesday, July 17, 2019 at 10:00 A.M

280 Grove Street Jersey City, New Jersey 07302 Robert Byrne, R.M.C., City Clerk Scan J. Gallagher, R.M.C., Deputy City Clerk Roiando R, Lavarro, Jr., Councilperson-at-Large Daniel Rivers, Councilperson-at-Largc Joyce E. Wattcrman, Councilperson-•at-Large Dcnise Ridley, Councilperson, Ward A Mira Prinx-Arey, Councilperson, Ward B Richard Boggiano, Councilperson, Ward C Michael Yun, Councilperson, Ward D James Solomon, Councilperson, Ward E JermaineD. Robinson, Councilpcrson, Ward F Agenda Regular Meeting of the Municipal Council Wednesday, July 17, 2019 at 10:00 a.m. Please Note: The next caucus meeting of Council is scheduled for Monday, August 12,2019 at 10:00 a.m. in the Efrain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City Hall. The next regular meeting of Council is scheduled for Wednesday, August 14,2019 at 10:00 a.m. in the Anna and Anthony R. Cucci Memorial Council Chambers, City Hall. A pre-meeting caucus may be held in the Efrain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City Hall. 1. (a) INVOCATION: (b) ROLL CALL: (c) SALUTE TO THE FLAG: (d) STATEMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH SUNSHINE LAW: City Clerk Robert Byrne stated on behalf of the Municipal Council. "In accordance with the New Jersey P.L. 1975, Chapter 231 of the Open Public Meetings Act (Sunshine Law), adequate notice of this meeting was provided by mail and/or fax to The Jersey Journal and The Reporter. Additionally, the annual notice was posted on the bulletin board, first floor of City Hall and filed in the Office of the City Clerk on Thursday, December 20, 2018, indicating the schedule of Meetings and Caucuses of the Jersey City Municipal Council for the calendar year 2019. -

WJ Washington Update

July 25, 2014 Washington Update This Week in Congress . House – The House passed the “STELA Reauthorization Act” (H.R. 4572); the “Empowering Students Through Enhanced Financial Counseling Act” (H.R. 4984); the “Student and Family Tax Simplification Act” (H.R, 3393); and the “Child Tax Credit Improvement Act of 2014” (H.R. 4935). Senate – The Senate invoked cloture on the motion to proceed to the “Bring Jobs Home Act” (S. 2569) by a vote of 93-7. The Senate completed the Rule 14 process for S. 2648 to make emergency supplemental appropriations for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2014; and reached an agreement to begin consideration of the “Highway and Transportation Funding Act of 2014” (H.R. 5021) to provide an extension of Federal-aid highway, highway safety, motor carrier safety, transit, and other programs funded by the Highway Trust Fund. Next Week in Congress . House – The House will consider four bills on endangered species pursuant to a rule; as well as the “Sunscreen Innovation Act” (H.R. 4250); the “National Cybersecurity and Critical Infrastructure Protection Act” (H.R. 3696); and the “Critical Infrastructure Research and Development Act” (H.R. 2952). The House may also consider legislation to address the ongoing immigration crisis on U.S.-Mexico border. Senate – The Senate is expected to begin consideration of S. 2648, a bill making emergency supplemental appropriations for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2014. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) is expected to seek cloture on the “Bring Jobs Home Act” (S. 2569), which would bar companies from deducting expenses of moving personnel or operations overseas and provide a 20 percent tax credit for returning operations from overseas. -

Midair Scare Brings Probe of 777S Turer Is Increasingly Hosting Crazereaches Beyond Shares Drive-Through Job Fairsand Rais- Favoredonsocial Media

P2JW053000-6-A00100-27FFFF5178F ADVERTISEMENT Meetour new, easy-to-use trading platform: thinkorswim® Web. LearnmoreonpageR10. ****** MONDAY,FEBRUARY 22, 2021 ~VOL. CCLXXVII NO.42 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 Last week: DJIA 31494.32 À 35.92 0.1% NASDAQ 13874.46 g 1.6% STOXX 600 414.88 À 0.2% 10-YR. TREASURY g 1 11/32 , yield 1.344% OIL $59.24 g $0.23 EURO $1.2120 YEN 105.43 Texas Thaws Out and Repairs Begin on Damage From the Cold Housing, What’s News Online Shopping Business&Finance Propel trength in housing and e- Scommerce during the pan- demic has helped propel hiring JobGains in blue-collar jobs,with em- ployment in some categories exceeding precrisis levels. A1 Blue-collar workers The jump this month in see boom, but some U.S. government-bond yields is sending tremors companies can’t find through stocks and forcing enough qualified help investorstomoreseriously confront the implications BY SARAH CHANEY CAMBON of rising interest rates. A1 Agroup of activist inves- GES TheU.S.’sblue-collar work- tors has abig stakeinKohl’s IMA forcehas begun to benefit from and is attempting to take astrengthening job market. control of the department- GETTY An Orlando,Fla.-area home store chain’s board. B1 AN/ builderisseeking to add four construction workerstoasix- M&T Bank is nearing a SULLIV person team in the midst of deal to acquire People’s TIN soaring housing demand during United Financial for more JUS SHELTER: Plumber Randy Calazans repaired a burst pipe in a home in HoustoN on Sunday, as temperatures climbed and the pandemic.InAtlanta, a than $7 billion, in the lat- Texas started to recover from severe weather that overwhelmed its power grid, leaving homes without heat for days. -

'Good Things Will Happen'

INSIDE TODAY: Cosby told police his accuser didn’t rebuff his advances / A3 JUNE 9, 2017 JASPER, ALABAMA — FRIDAY — WWW.MOUNTAINEAGLE.COM 75 CENTS CORRECTION WALKER COUNTY SHERIFF’S OFFICE INSIDE Search underway for suspect in weekend murder in east Walker By JENNIFER COHRON “He was still breathing but was not conscious,” In Thursday’s edi- Daily Mountain Eagle Leach said. tion of the Daily The vehicle had struck a power pole at the inter- Mountain Eagle, a The Walker County Sheriff’s section of Smoot Street and Church Street, and Fos- story announcing Office is searching for a person of ter was bleeding from the head, according to Leach. interest after a shooting in Quin- The shooting is believed to have occurred on the Relay for Life of ton over the weekend left one Bobby Taylor Street, Leach said. Comey says he Walker County man dead. Foster was transported to UAB Hospital, where was fired because would be held on Anthony Foster, 36, died he was placed on life support before dying Wednes- Saturday said later Wednesday night at UAB Hospi- day at 9:51 p.m. of investigation tal, according to Sgt. Anthony Leach said an arrest warrant for murder is being WASHINGTON (AP) — in the story that the Leach. obtained for Tavaris Johnson. event was on Fri- Patrol deputies, responding to Johnson is not believed to be in Walker County Former FBI Director James day. a call received at 2:04 p.m. Sun- at this time. Comey asserted Thursday day, found Foster behind the That was incor- Tavaris Anyone with information about Johnson’s where- that President Donald wheel of his truck suffering from abouts is asked to call the Walker County Sheriff’s Trump fired him to interfere rect, as the event gunshot wounds. -

Committee Meeting Of

You're viewing an archived copy from the New Jersey State Library. Committee Meeting of ASSEMBLY TRANSPORTATION, PUBLIC WORKS AND INDEPENDENT AUTHORITIES COMMITTEE "The Commissioner of Transportation and other experts on transportation matters in the State of New Jersey will testify regarding the repair and rehabilitation of the Pulaski Skyway and other issues concerning the Department of Transportation" ASSEMBLY BILL No. 3529 “Designates Paterson Plank Road bridge in the Town of Secaucus as “Joseph F. Tagliareni Jr. Memorial Bridge” LOCATION: Hudson County Community College DATE: February 28, 2013 North Hudson Higher Education Center 9:30 a.m. Union City, New Jersey MEMBERS OF COMMITTEE PRESENT: Assemblyman John S. Wisniewski, Chair Assemblywoman Linda Stender, Vice Chair Assemblyman Upendra J. Chivukula Assemblyman Thomas P. Giblin Assemblyman Charles S. Mainor Assemblyman Ruben J. Ramos Jr. Assemblywoman Valerie Vainieri Huttle Assemblywoman Nancy F. Munoz Assemblyman Brian E. Rumpf ALSO PRESENT: Charles A. Buono Jr. Aaron Binder Glen Beebe Patrick Brennan Assembly Majority Assembly Republican Office of Legislative Services Committee Aide Committee Aide Committee Aides Meeting Recorded and Transcribed by The Office of Legislative Services, Public Information Office, Hearing Unit, State House Annex, PO 068, Trenton, New Jersey You're viewing an archived copy from the New Jersey State Library. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Glen E. Gabert, Ph.D. President Hudson County Community College 2 Thomas A. DeGise County Executive Hudson County, and First Vice Chair Executive Committee North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority 6 Jerramiah T. Healy Mayor City of Jersey City 12 Steven Fulop Councilman Ward E City of Jersey City 20 Anthony J. -

NEWS RELEASE Law Enforcement Respond To: Commission P.O

Election NEWS RELEASE Law Enforcement Respond to: Commission P.O. Box 185 Trenton, New Jersey 08625-0185 E EC L 1973 (609) 292-8700 or Toll Free Within NJ 1-888-313-ELEC (3532) CONTACT: JOSEPH DONOHUE FOR RELEASE: DEPUTY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR JANUARY 22, 2015 Newark and Jersey City have been the state’s top political battlegrounds among municipalities and counties during the past 40 years, according to a new analysis by the New Jersey Election Law Enforcement Commission (ELEC). Among the most costly 25 municipal or county elections since 1974, Newark hosted seven, while Jersey City had nine, according to “White Paper No. 25- Top Local Elections in New Jersey-A Tale of Two Cities and More.” Joseph Donohue, ELEC’s Deputy Director, authored the study. While Jersey City had more marquee races, elections in Newark, the state’s largest city by population, have been drawn the biggest bucks. Four of the top five most expensive elections took place in Newark. The 2006 election, when adjusted for inflation, ranks highest. Table 1 Top 10 Most Expensive Local Races in New Jersey AMOUNT AMOUNT LOCATION YEAR TYPE (IN 2014 KEY RACE (UNADJUSTED) DOLLARS) Cory Booker defeats Ronald Rice Newark 2006 Municipal $11,437,051 $13,439,543 for mayor. Ras Baraka defeats Shavar Jeffries Newark 2014 Municipal $12,562,933 $12,562,933 for mayor. Mayor Sharpe James defeats Cory Newark 2002 Municipal $ 8,692,816 $11,437,916 Booker. Mayor Cory Booker defeats Newark 2010 Municipal $ 9,827,153 $10,670,090 Clifford Minor. Bergen Dennis McNerney defeats Henry 2002 General $ 7,667,682 $10,089,055 County McNamara for Executive. -

Taliban Try to Breach Bagram U.S

GOLF MILITARY FACES Woods making Turks warn sanctions ‘The Mandalorian’ unique mark on could threaten US gives female directors President’s Cup access to Incirlik a chance to shine Back page Page 3 Page 14 DOD to review vetting procedures for foreign military students » Page 8 stripes.com Volume 78, No. 171 ©SS 2019 THURSDAY, DECEMBER 12, 2019 50¢/Free to Deployed Areas Watchdog to review use of US troops at border BY DAN LAMOTHE The Washington Post The top government watchdog overseeing the Pentagon will re- view how U.S. troops have been used on the southern border, say- ing he has received “several re- quests” to do so. Acting Defense Department Inspector General Glenn Fine said his office will examine what the service members are doing, what training they received and whether they have complied with laws, Pentagon policy and operat- ing guidelines they received. “We intend to conduct this important evaluation as expedi- tiously as possible,” Fine said in a statement to The Washington Post. The decision comes after 34 members of the House requested a review in September, according to a letter that Fine sent Rep. Raul Grijalva, D-Ariz., on Tuesday. “We have carefully reviewed your request — as well as consid- ered other factors — and have de- cided to initiate an evaluation of Taliban try to breach Bagram U.S. military operations along the southern border,” Fine wrote. Fine said in a memo to Defense Secretary Mark Esper and other US airstrikes end daylong battle after senior defense officials on Tues- day that he is requesting several insurgents blast hospital near base different military commands to provide a main point of contact for the project. -

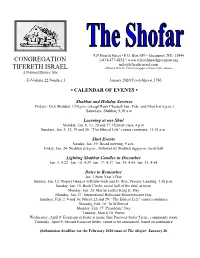

January 2020 Shofar

519 Fourth Street • P.O. Box 659 • Greenport, NY, 11944 CONGREGATION 1-631-477-0232 • www.tiferethisraelgreenport.org [email protected] TIFERETH ISRAEL IN This issueAffiliated With The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism A National Historic Site E-Volume 22 Number 1 January 2020/Tevet-Shevat 5780 • CALENDAR OF EVENTS • Shabbat and Holiday Services Fridays: Erev Shabbat, 7:30 p.m. [except Rosh Chodesh Jan., Feb., and March at 6 p.m.] Saturdays: Shabbat, 9:30 a.m. Learning at our Shul Monday, Jan. 6, 13, 20 and 27: Hebrew class, 4 p.m. Sundays, Jan. 5, 12, 19 and 26: “The Ethical Life” course continues, 11:30 a.m. Shul Events Sunday, Jan. 19: Board meeting, 9 a.m. Friday, Jan. 24: Shabbat at 6 p.m., followed by Shabbat supper in social hall Lighting Shabbat Candles in December Jan. 3: 4:22 Jan. 10: 4:29 Jan. 17: 4:37 Jan. 24: 4:45. Jan. 31: 4:54 Dates to Remember Jan. 1:New Year’s Day Sunday, Jan. 12: Project Genesis w/Rabbi Gadi and Fr. Roy, Peconic Landing, 1:30 p.m. Sunday, Jan. 15: Book Circle, social hall of the shul, at noon Monday, Jan. 20: Martin Luther King Jr. Day Monday, Jan. 27: International Holocaust Remembrance Day Sundays, Feb. 2, 9 and 16; March 22 and 29: “The Ethical Life” course continues Monday, Feb. 10: Tu B’Shevat Monday, Feb. 17: Presidents’ Day Tuesday, March 10: Purim Wednesday, April 8: Ecumenical Seder at noon; first Passover Seder 5 p.m., community room Thursday, April 9: Second Passover Seder, venue to be announced, based on attendance (Submission deadline for the February 2020 issue of The Shofar: January 20 From The Rabbi… “Fifty Shades of Light” Recently, I was privileged to be invited to the 11th annual Congressional bipartisan Hanukkah celebration at the Library of Congress.