Accepted Manuscript, to Appear in Astronomy and Geophysics in Spring 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First President of the IAU, Benjamin Baillaud

Under One Sky – the IAU Centenary Symposium Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 349, 2019 c 2019 International Astronomical Union D. Valls-Gabaud, C. Sterken & J.B. Hearnshaw eds. DOI: 00.0000/X000000000000000X The first President of the IAU, Benjamin Baillaud Jean-Louis Bougeret Observatoire de Paris – Universit´ePSL Laboratoire d’Etudes Spatiales et d’Instrumentation en Astrophysique (LESIA) F-92195 Meudon, France email: [email protected] Abstract. Benjamin Baillaud was appointed president of the First Executive Committee of the International Astronomical Union which met in Brussels during the Constitutive Assembly of the International Research Council (IRC) on July 28th, 1919. He served in this position until 1922, at the time of the First General Assembly of the IAU which took place in Rome, May 2–10. At that time, Baillaud was director of the Paris Observatory. He had previously been director of the Toulouse Observatory for a period of 30 years and Dean of the School of Sciences of the University of Toulouse. He specialized in celestial mechanics and he was a strong supporter of the “Carte du Ciel” project; he was elected chairman of the permanent international committee of the Carte du Ciel in 1909. He also was the founding president of the Bureau International de l’Heure (BIH) and he was directly involved in the coordination of the ephemerides at an international level. In this paper, we present some of his activities, particularly those concerning international programmes, for which he received international recognition and which eventually led to his election in 1919 to the position of first president of the IAU. -

The First President of the IAU, Benjamin Baillaud

Under One Sky: The IAU Centenary Symposium Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 349, 2019 c International Astronomical Union 2019 C. Sterken, J. Hearnshaw & D. Valls-Gabaud, eds. doi:10.1017/S1743921319000231 The first President of the IAU, Benjamin Baillaud Jean-Louis Bougeret Observatoire de Paris – Universit´ePSL Laboratoire d’Etudes Spatiales et d’Instrumentation en Astrophysique (LESIA) F-92195 Meudon, France email: [email protected] Abstract. Benjamin Baillaud was appointed president of the First Executive Committee of the International Astronomical Union which met in Brussels during the Constitutive Assembly of the International Research Council (IRC) on July 28th, 1919. He served in this position until 1922, at the time of the First General Assembly of the IAU which took place in Rome, May 2–10. At that time, Baillaud was director of the Paris Observatory. He had previously been director of the Toulouse Observatory for a period of 30 years and Dean of the School of Sciences of the University of Toulouse. He specialized in celestial mechanics and he was a strong supporter of the “Carte du Ciel” project; he was elected chairman of the permanent international committee of the Carte du Ciel in 1909. He also was the founding president of the Bureau International de l’Heure (BIH) and he was directly involved in the coordination of the ephemerides at an international level. In this paper, we present some of his activities, particularly those concerning international programmes, for which he received international recognition and which eventually led to his election in 1919 to the position of first president of the IAU. -

L'annuaire Du Bureau Des Longitudes75

L’Annuaire du Bureau des longitudes (1795-1932) Colette Le Lay To cite this version: Colette Le Lay. L’Annuaire du Bureau des longitudes (1795-1932). 8, 2021, Collection du Bureau des longitudes, 978-2-491688-04-2. halshs-03233204 HAL Id: halshs-03233204 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03233204 Submitted on 24 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Collection du Bureau des longitudes Volume 8 Colette Le Lay L’Annuaire du Bureau des longitudes (1795 - 1932) Collection du Bureau des longitudes - Volume 8 Colette Le Lay Bureau des longitudes © Bureau des longitudes, 2021 ISBN : 978-2-491688-05-9 ISSN : 2724-8372 Préface C’est avec grand plaisir que le Bureau des longitudes accueille dans ses éditions l’ouvrage de Colette Le Lay consacré à l’Annuaire du Bureau des longitudes. L’Annuaire est la publication du Bureau destinée aux institutions nationales, aux administrations1 et au grand public, couvrant, selon les époques, des domaines plus étendus que l’astronomie, comme la géographie, la démographie ou la physique par exemple. Sa diffusion est par nature plus large que celle des éphémérides et des Annales, ouvrages spécialisés destinés aux professionnels de l’astronomie ou de la navigation. -

Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the Context of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention

Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the context of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention Thematic Study, vol. 2 Clive Ruggles and Michel Cotte with contributions by Margaret Austin, Juan Belmonte, Nicolas Bourgeois, Amanda Chadburn, Danielle Fauque, Iván Ghezzi, Ian Glass, John Hearnshaw, Alison Loveridge, Cipriano Marín, Mikhail Marov, Harriet Nash, Malcolm Smith, Luís Tirapicos, Richard Wainscoat and Günther Wuchterl Edited by Clive Ruggles Published by Ocarina Books Ltd 27 Central Avenue, Bognor Regis, West Sussex, PO21 5HT, United Kingdom and International Council on Monuments and Sites Office: International Secretariat of ICOMOS, 49–51 rue de la Fédération, F–75015 Paris, France in conjunction with the International Astronomical Union IAU–UAI Secretariat, 98-bis Blvd Arago, F–75014 Paris, France Supported by Instituto de Investigaciones Arqueológicas (www.idarq.org), Peru MCC–Heritage, France Royal Astronomical Society, United Kingdom ISBN 978–0–9540867–6–3 (e-book) ISBN 978–2–918086–19–2 (e-book) © ICOMOS and the individual authors, 2017 All rights reserved A preliminary version of this publication was presented at a side-event during the 39th session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee (39COM) in Bonn, Germany, in July 2015 Front cover photographs: Star-timing device at Al Fath, Oman. © Harriet Nash Pic du Midi Observatory, France. © Claude Etchelecou Chankillo, Peru. © Iván Ghezzi Starlight over the church of the Good Shepherd, Tekapo, New Zealand. © Fraser Gunn Table of contents Preface ...................................................................................................................................... -

L'annuaire Du Bureau Des Longitudes (1795

Collection du Bureau des longitudes Volume 8 Colette Le Lay L’Annuaire du Bureau des longitudes (1795 - 1932) Collection du Bureau des longitudes - Volume 8 Colette Le Lay Bureau des longitudes © Bureau des longitudes, 2021 ISBN : 978-2-491688-05-9 ISSN : 2724-8372 Préface C’est avec grand plaisir que le Bureau des longitudes accueille dans ses éditions l’ouvrage de Colette Le Lay consacré à l’Annuaire du Bureau des longitudes. L’Annuaire est la publication du Bureau destinée aux institutions nationales, aux administrations1 et au grand public, couvrant, selon les époques, des domaines plus étendus que l’astronomie, comme la géographie, la démographie ou la physique par exemple. Sa diffusion est par nature plus large que celle des éphémérides et des Annales, ouvrages spécialisés destinés aux professionnels de l’astronomie ou de la navigation. De fait l’Annuaire est sans aucun doute la publication du Bureau la plus connue du public et sa parution régulière repose sur les bases légales de la fondation de l’institution lui enjoignant de présenter chaque année au Corps Législatif un Annuaire propre à régler ceux de toute la République. L’ouvrage de Mme Le Lay couvre l’histoire de l’Annuaire sur la période allant de la création du Bureau des longitudes en 1795 jusqu’à 1932. L’auteure nous décrit les évolutions de son contenu au cours du temps, les acteurs qui le réalisent et ses utilisateurs. On y verra que les changements ont été grands entre l’opuscule hésitant de ses débuts, qui se limitait à quelques renseignements astronomiques sur les levers-couchers du Soleil et de la Lune, les éclipses et déjà les poids et mesures, et les imposants volumes du XIXe siècle avec des tables de toutes natures et des notices scientifiques étoffées. -

Iau Commission C3 Newsletter

IAU COMMISSION C3 NEWSLETTER HISTORY OF ASTRONOMY Welcome to the winter solstice edition of the newsletter We wish everyone health and happiness in the new year. of IAU Commission C3 (History of Astronomy). This The next issue of the newsletter will be in June 2021. issue features the announcement of a new Project Group Please send our Secretary any news you would like us to and reports of pre-existing Working Groups and Project include. Groups since the last newsletter in June 2020. It contains Sara Schechner, Secretary news of upcoming conferences, reports of recent Wayne Orchiston, President meetings, a list of notable publications, and tables of Christiaan Sterken, Vice-President content from a journal devoted to the history of astronomy. The newsletter also contains announcements of research and PhD opportunities in the history of TABLE OF CONTENTS astronomy as well as an introduction to a new Ourania Network. And of course, you will find news from Reports of Working Groups & Project Groups 2 members, announcements of awards, and obituaries. Making History 15 Oral History 24 We are excited to introduce some new sections to the Art & Exhibitions 26 newsletter. The “Making History” section includes Announcements 30 reports on the Astronomy Genealogy Project (AstroGen), Awards and Honors 34 analysis of the Vatican Observatory’s guest book, and the News from Members 35 rescue of a medieval manuscript by Lewis of Caerleon. In In Memoriam 37 the “Oral History” section, there is a first-hand account Notable Publications 39 of the founding of the Journal of Astronomical History and Journal Contents 41 Heritage. -

A Topical Index to the Main Articles in Mercury Magazine (1972 – 2019) Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U

A Topical Index to the Main Articles in Mercury Magazine (1972 – 2019) Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco) [Mar. 9, 2020] Note: This index, organized by subject matter, only covers the longer articles in the Astronomical Society of the Pacific’s popular-level magazine; it omits news notes, regular columns, Society doings, etc. Within each subject category, articles are listed in chronological order starting with the most recent one. Table of Contents Impacts Amateur Astronomy Infra-red Astronomy Archaeoastronomy Interdisciplinary Topics Asteroids Interstellar Matter Astrobiology Jupiter Astronomers Lab Activities Astronomy: General Light in Astronomy Binary Stars Light Pollution Black Holes Mars Comets Mercury Cosmic Rays Meteors and Meteorites Cosmology Moon Distances in Astronomy Nebulae Earth Neptune Eclipses Neutrinos Education in Astronomy Particle Physics & Astronomy Exoplanets Photography in Astronomy Galaxies Pluto Galaxy (The Milky Way) Pseudo-science (Debunking) Gamma-ray Astronomy Public Outreach Gravitational Lenses Pulsars and Neutron Stars Gravitational Waves Quasars and Active Galaxies History of Astronomy Radio Astronomy Humor in Astronomy Relativity and Astronomy 1 Saturn Sun SETI Supernovae & Remnants Sky Phenomena Telescopes & Observatories Societal Issues in Astronomy Ultra-violet Astronomy Solar System (General) Uranus Space Exploration Variable Stars Star Clusters Venus Stars & Stellar Evolution X-ray Astronomy _______________________________________________________________________ Amateur Astronomy Hostetter, D. Sidewalk Astronomy: Bridge to the Universe, 2013 Winter, p. 18. Fienberg, R. & Arion, D. Three Years after the International Year of Astronomy: An Update on the Galileoscope Project, 2012 Autumn, p. 22. Simmons, M. Sharing Astronomy with the World [on Astronomers without Borders], 2008 Spring, p. 14. Williams, L. Inspiration, Frame by Frame: Astro-photographer Robert Gendler, 2004 Nov/Dec, p. -

Notices Biographiques

Notices biographiques Ce document, réalisé par Jean-Claude Pecker, comporte de courtes notices d'abord sur les savants ayant fréquenté l'Académie de Mersenne et celles de Montmor et Thévenot, puis sur les Membres et Correspondants français de l'Académie des sciences présentées par ordre chronologique de leur entrée à l'Académie des sciences. Il se termine par des notices sur les astronomes français importants, presque contemporains, qui auraient pu être élus à l'Académie des sciences. N.B. : Jean-Claude Pecker remercie M. Philippe Véron, pour l'avoir autorisé à se servir de son Dictionnaire des astronomes français pour la rédaction des notices sur les astronomes ayant été actifs après 1850 et avant 1950. Il tient à préciser qu'il s'est également inspiré de notices existantes ; il assume cette responsabilité auprès des nombreux auteurs, le plus souvent anonymes, dont il a utilisé les écrits. Autour de l'Académie de Mersenne Nicolas Claude FABRI (1580 - 1637), du village de Peyresq - autrement dit Nicolas PEIRESC - est né en 1580, l'année de la première édition des Essais de Montaigne. Ce juriste, ce politique, était aussi un humaniste convaincu. Il entretint des relations épistolaires suivies avec de nombreux intellectuels, Malherbe, Gassendi, Mersenne... Il a été en correspondance avec Galilée qui lui a confié une lunette. Peiresc observa le ciel de sa Provence natale, et fit d'importantes découvertes : celle de la nébuleuse d'Orion par exemple. A la veille de sa mort, il avait entrepris une cartographie de la Lune, jamais aboutie. Jean-Baptiste MORIN (1583 - 1656) né à Villefranche-sur-Saône, étudia à Aix, puis à Avignon. -

Figure 7.1: Observatoire De Paris (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Figure 7.1: Observatoire de Paris (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt) 76 7. Astronomy and Astrophysics at the Observatoire de Paris in the Belle Epoque Suzanne Débarbat (Paris, France) Abstract field of celestial mechanics in the world including uses for space research. The Belle Epoque considered at the Paris Observatory lies Such was the man to whom Admiral Ernest Mouchez from about two decades before 1900 up to the beginning of had to succeed. At the death of Le Verrier, in 1877, World War I. Four directors were at its head during those Mouchez was a man of experience, fiftysix years old years: Admiral Ernest Barthélémy Mouchez (1821–1892) being an officer from the French Navy, who had made from 1878 up to 1892, François-Félix Tisserand (1845–1896) hydrographic campaigns in South America, Asia, Africa. during only four years between 1892 and 1896, Maurice Mouchez was also an astronomical observer of the 1874 Lœwy (1833–1907) from 1897 to 1907 and Benjamin Baillaud transit of Venus, in view of a new determination of the (1848–1934) from 1908 up to 1926, a long mandate which solar parallax. He was just called to be contre-amiral in ended seven years after the end of World War I. All of them 1878 when asked to be director of the Paris Observatory have marked the Observatory and its activities in different the same year. fields. 7.2 Admiral Mouchez’s Program and Realizations 7.1 Admiral Mouchez, a Difficult Succession at the Head of the In 1847, when attending a meeting of the British Asso- ciation for Advancement of Science in Oxford, Le Ver- Observatory rier had a lodging close to F. -

No Slide Title

The IAU–UNESCO Astronomy and World Heritage Initiative and the Pic-du-Midi Observatory Clive Ruggles Photo: Pic du Midi in 1920 © Régie du Pic du Midi/Observatoire Midi Pyrénées Inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 2005: The northernmost node of the Arc The Struve Geodetic Arc A triangulation network extending from Hammerfest in Norway down to the Black Sea 2,820 km long Constructed between 1816 and 1855 by Friedrich Georg Wilhelm Struve to measure the precise size and shape of the Earth First precise measurement of a long segment of a meridian (Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Lituania, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova) IAU 22nd General Assembly, The Hague, 1994 Resolution B10, proposed by C41 (History of Astronomy) “Urges the Executive Committee of the IAU to approach the governments of … Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, Poland and Moldova … with a view to … an approach to UNESCO to declare them to be World Heritage Sites” The Struve Geodetic Arc, by James R. Smith, International Federation of Surveyors [FIG], (2005) IAU 22nd General Assembly, The Hague, 1994 Resolution B10, proposed by C41 (History of Astronomy) “Urges the Executive Committee of the IAU to approach the governments of … Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Belarus, [Russia] and Moldova … with a view to … an approach to UNESCO to declare them to be World Heritage Sites” The Struve Geodetic Arc, by James R. Smith, International Federation of Surveyors [FIG], (2005) World Heritage 1121 WH properties [sites, monuments and landscapes] (2019) of which 869 are cultural; 213 are natural; 39 are mixed. -

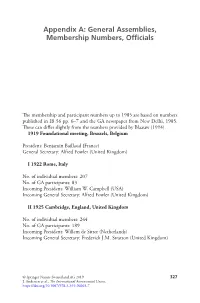

Appendix A: General Assemblies, Membership Numbers, Officials

Appendix A: General Assemblies, Membership Numbers, Officials The membership and participant numbers up to 1985 are based on numbers published in IB 56 pp. 6–7 and the GA newspaper from New Delhi, 1985. These can differ slightly from the numbers provided by Blaauw (1994). 1919 Foundational meeting, Brussels, Belgium President: Benjamin Baillaud (France) General Secretary: Alfred Fowler (United Kingdom) I 1922 Rome, Italy No. of individual members: 207 No. of GA participants: 83 Incoming President: William W. Campbell (USA) Incoming General Secretary: Alfred Fowler (United Kingdom) II 1925 Cambridge, England, United Kingdom No. of individual members: 244 No. of GA participants: 189 Incoming President: Willem de Sitter (Netherlands) Incoming General Secretary: Frederick J.M. Stratton (United Kingdom) © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 327 J. Andersen et al., The International Astronomical Union, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96965-7 328 Appendix A: General Assemblies, Membership Numbers, Officials III 1928 Leiden, Netherlands No. of individual members: 288 No. of GA participants: 261 Incoming President: Frank W. Dyson (United Kingdom) General Secretary: Frederick J.M. Stratton (United Kingdom) V 1932 Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States No. of individual members: 406 No. of GA participants: 203 Incoming President: Frank Schlesinger (USA) General Secretary: Frederick J.M. Stratton (United Kingdom) V 1935 Paris, France No. of individual members: 496 No. of GA participants: 317 Incoming President: Ernest Esclangon (France) General Secretary: Frederick J.M. Stratton (United Kingdom) VI 1938 Stockholm, Sweden No. of individual members: 554 No. of GA participants: 293 President: Arthur S. Eddington (United Kingdom) until 1944, then Harold Spencer-Jones (United Kingdom) General Secretary: Jan H. -

History of Science March 2001.Indd

Hist. Sci., xxxix (2001) THE SINGLE EYE: RE-EVALUATING ANCIEN RÉGIME SCIENCE Jimena Canales Harvard University Free astronomy is almost as dangerous as the free press. Victor Hugo INTRODUCTION In his historical work Victor Hugo, and many careful observers since then, have seen the Paris Observatory as a crucial site of interaction between science and the state. His distressing history was one of failure: once again the dream of 1789 had been crushed, and for the second time, by a Napoleon. Napoleon III’s paranoid regime brutally controlled everything — even astronomy. Hugo exposed the illicit relations between the Second Empire (1851–70) and astronomy by denouncing the fall from power of François Arago, the Director of the Observatory who refused to support the Imperial regime, and by lamenting his replacement by Urbain Le Verrier, also known as the “Haussmann of the stars” after Napoleon III’s urban planning strong hand.1 In Napoleon the Little, Victor Hugo explained: “Free astronomy is almost as dangerous as the free press.”2 While posterity has forgotten Hugo’s history of the Paris Observatory, historians still consider the Observatory an exemplary site for linking science and the state. In fact, French politics seemed to map almost seamlessly onto the different regimes of the Paris Observatory, where directors came and went with the nineteenth-century’s tortuous succession of revolutions and coups d’état. Three of the Observatory’s directorships appeared to be especially at the mercy of different political regimes: Cassini IV to Louis XVI, Arago to the July Monarchy and the Second Republic, and Le Verrier to the Second Empire.