Super Whitman 1855

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II a Master's Thesis Presented to College of Arts & Sciences Departmen

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II A Master’s Thesis Presented To College of Arts & Sciences Department of Communications and Humanities _______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree _______________________________ SUNY Polytechnic Institute By David Dellecese May 2018 © 2018 David Dellecese Approval Page SUNY Polytechnic Institute DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS AND HUMANITIES INFORMATION DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY MS PROGRAM Approved and recommended for acceptance as a thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Design + Technology. _________________________ DATE ________________________________________ Kathryn Stam Thesis Advisor ________________________________________ Ryan Lizardi Second Reader ________________________________________ Russell Kahn Instructor 1 ABSTRACT American comic books were a relatively, but quite popular form of media during the years of World War II. Amid a limited media landscape that otherwise consisted of radio, film, newspaper, and magazines, comics served as a useful tool in engaging readers of all ages to get behind the war effort. The aims of this research was to examine a sampling of messages put forth by comic book publishers before and after American involvement in World War II in the form of fictional comic book stories. In this research, it is found that comic book storytelling/messaging reflected a theme of American isolation prior to U.S. involvement in the war, but changed its tone to become a strong proponent for American involvement post-the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This came in numerous forms, from vilification of America’s enemies in the stories of super heroics, the use of scrap, rubber, paper, or bond drives back on the homefront to provide resources on the frontlines, to a general sense of patriotism. -

Planner Grafton Says Department Behind the Times

Holiday gift guide inside this week's NewArk Post Chrysler may lay off 1,700 /2a · State playoffs open /lh Vol. 76, No. 73 November 11, 1987 Newark, Del. COVER STORY Planner Grafton says department behind the times by Cathy Thomas '' We're not . ~Nture New Castle County is boom ing. Houses are springing up at enough as an · ~ every turn, business construc tion is running apace and silhouetted against the skyline to be a role-model are nearly as many cranes as trees. II Trying to cope with this un paralleled growth is a planning to get in vogue with contem department still in its infancy. porary planning programs. That is the assessment of "I don't mean we need to be on Wayne Grafton, New Castle the cutting edge. We need to County's planning director, who have codes and ordinances that readily admits to a reputation are at least cognizant of contem for causing a ripple. porary planning principles." ·· · rom where 1 sit, we've Grafton stepped into the rQle made marvelous strides," says of New Castle county's planning Grafton, "and, yet, it's not director three years ago. enough." "Administratively, this place Grafton doesn't expect the was a mess." According to Graf county to "pull itself out of the ton, employees in the depart- woods" for another three or four Salem Woods is just one of many new developments being constructed in New Castle County. years. He would like the county See GRAFTON/12a Purzycki: Plan Comprehen~ive· plan must he specific out by year's end If the new comprehensive plan for New Castle Coun The much-awaited com posals now before the Delaware ty refers to lofty, sentimental goals, then it's not doing prehensive plan for New Castle legislature. -

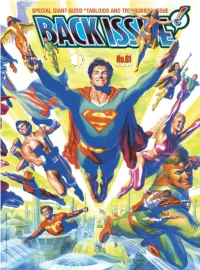

Dec. 2012 $10.95

D e c . 2 0 1 2 No.61 $10.95 Legion of Super-Heroes TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Rights All Comics. DC © & TM Super-Heroes of Legion Volume 1, Number 61 December 2012 EDITOR-IN- CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER FLASHBACK: The Perils of the DC/Marvel Tabloid Era . .1 Rob Smentek Pitfalls of the super-size format, plus tantalizing tabloid trivia SPECIAL THANKS BEYOND CAPES: You Know Dasher and Dancer: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Rein- Jack Abramowitz Dan Jurgens deer . .7 Neal Adams Rob Kelly and The comics comeback of Santa and the most famous reindeer of all Erin Andrews TreasuryComics.com FLASHBACK: The Amazing World of Superman Tabloids . .11 Mark Arnold Joe Kubert A planned amusement park, two movie specials, and your key to the Fortress Terry Austin Paul Levitz Jerry Boyd Andy Mangels BEYOND CAPES: DC Comics’ The Bible . .17 Rich Bryant Jon Mankuta Kubert and Infantino recall DC’s adaptation of the most spectacular tales ever told Glen Cadigan Chris Marshall FLASHBACK: The Kids in the Hall (of Justice): Super Friends . .24 Leslie Carbaga Steven Morger A whirlwind tour of the Super Friends tabloid, with Alex Toth art Comic Book Artist John Morrow Gerry Conway Thomas Powers BEYOND CAPES: The Secrets of Oz Revealed . .29 DC Comics Alex Ross The first Marvel/DC co-publishing project and its magical Marvel follow-up Paul Dini Bob Rozakis FLASHBACK: Tabloid Team-Ups . .33 Mark Evanier Zack Smith The giant-size DC/Marvel crossovers and their legacy Jim Ford Bob Soron Chris Franklin Roy Thomas INDEX: Bronze Age Tabloids Checklist . -

No.61 2 1 0 2

D e c . 2 0 1 2 No.61 $10.95 Legion of Super-Heroes TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Rights All Comics. DC © & TM Super-Heroes of Legion Volume 1, Number 61 December 2012 EDITOR-IN- CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER FLASHBACK: The Perils of the DC/Marvel Tabloid Era . .1 Rob Smentek Pitfalls of the super-size format, plus tantalizing tabloid trivia SPECIAL THANKS BEYOND CAPES: You Know Dasher and Dancer: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Rein- Jack Abramowitz Dan Jurgens deer . .7 Neal Adams Rob Kelly and The comics comeback of Santa and the most famous reindeer of all Erin Andrews TreasuryComics.com FLASHBACK: The Amazing World of Superman Tabloids . .11 Mark Arnold Joe Kubert A planned amusement park, two movie specials, and your key to the Fortress Terry Austin Paul Levitz Jerry Boyd Andy Mangels BEYOND CAPES: DC Comics’ The Bible . .17 Rich Bryant Jon Mankuta Kubert and Infantino recall DC’s adaptation of the most spectacular tales ever told Glen Cadigan Chris Marshall FLASHBACK: The Kids in the Hall (of Justice): Super Friends . .24 Leslie Carbaga Steven Morger A whirlwind tour of the Super Friends tabloid, with Alex Toth art Comic Book Artist John Morrow Gerry Conway Thomas Powers BEYOND CAPES: The Secrets of Oz Revealed . .29 DC Comics Alex Ross The first Marvel/DC co-publishing project and its magical Marvel follow-up Paul Dini Bob Rozakis FLASHBACK: Tabloid Team-Ups . .33 Mark Evanier Zack Smith The giant-size DC/Marvel crossovers and their legacy Jim Ford Bob Soron Chris Franklin Roy Thomas INDEX: Bronze Age Tabloids Checklist . -

The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis

University of Alberta Telling Stories About Storytelling: The Metacomics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Warren Ellis by Orion Ussner Kidder A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies ©Orion Ussner Kidder Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60022-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

The Eternal Green Lantern

Roy Tho mas ’ Mean & Green Comics Fan zine GREEN GROW THE LANTTEERRNNSS $7.95 NODELL, KANE, In the USA & THE CREATION OF A No.102 LEGEND— TIMES TWO! June 2011 06 1 82658 27763 5 Green Lantern art TM & ©2011 DC Comics Vol. 3, No. 102 / June 2011 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor TH Michael T. Gilbert NOW WI Editorial Honor Roll 16 PAGES Jerry G. Bails (founder) R! Ronn Foss, Biljo White OF COLO Mike Friedrich Proofreader Rob Smentek Cover Artists Mart Nodell, Gil Kane, & Terry Austin Contents Cover Colorists Writer/Editorial – “Caught In The Creative Act” . 2 Mart Nodell & Tom Ziuko The Eternal Green Lantern . 3 With Special Thanks to: Will Murray’s overview of the Emerald Gladiators of two comic book Ages. Heidi Amash Bob Hughes Henry Andrews Sean Howe “Marty Created ‘The Green Lantern’!” . 15 Finn Andreen Betty Tokar Jankovich Ger Apeldoorn Robert Kennedy Mart & Carrie Nodell interviewed about GL and other wonders by Shel Dorf. Terry Austin David Anthony Kraft Bob Bailey R. Gary Land “Life’s Not Over Yet!” . 31 Mike W. Barr Jim Ludwig Jim Beard Monroe Mayer Jack Mendelsohn on his comics and animation work (part 2), with Jim Amash. John Benson Jack Mendelsohn Jared Bond Raymond Miller Bob & Betty—& Archie & Betty . 44 Dominic Bongo Ken Moldoff An interview with the woman who probably inspired Betty Cooper—conducted by Shaun Clancy. Wendy Gaines Bucci Shelly Moldoff Mike Burkey Lynn Montana Glen Cadigan Brian K. -

Interviewing R. Sikoryak, Creator of the Unquotable Trump Written by Robert A

Pop-Culture & Trump: Interviewing R. Sikoryak, Creator of the Unquotable Trump Written by Robert A. Saunders This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Pop-Culture & Trump: Interviewing R. Sikoryak, Creator of the Unquotable Trump https://www.e-ir.info/2017/10/01/pop-culture-trump-interviewing-r-sikoryak-creator-of-the-unquotable-trump/ ROBERT A. SAUNDERS, OCT 1 2017 I recently sat down with Robert Sikoryak, who typically works under the name R. Sikoryak, to discuss his recent project The Unquotable Trump. Building on the artist’s expertise at adapting great works of literature to the comic book format, the collection of retooled iconic covers uses Trump’s bombastic quotes cast against fantastic scenes to satirize the U.S. president and his policies. With this explicitly political project, Sikoryak joins the ranks of other cartoonists who have turned their pen into a weapon against the billionaire reality-TV host-turned-leader of the free world, from Stephen Byrne’s ‘Trump Rally’ to Pia Guerra’s Bannon-Trump ‘Big Boy’ to the feminist anthology ‘Resist’. In many of Sikoryak’s depictions, Trump assumes the role of a super-powered antagonist, such as a winning- obsessed Magneto taking on the ‘Ex-Men’, an apish campaigner chastising ‘The Black Voter’, and a Dr. Doom-like overlord trying to nab some ‘Hombres Fantásticos’ (all of which reprise famous covers from Marvel ComicsThe ( Uncanny X-Men,The Black Panther, and The Fantastic Four, respectively). -

Gothic Genesis 6.5 MB

Mythos #3 Winter, 2019 In the beginning…Bob created the Batman. But, Batman was battle against the evil forces of society…his identity remains un- unformed and unfinished. And so, Bob brought his new creation known.” 2 This was a basic detective murder mystery thriller, in to his writer-friend Bill, who looked upon Batman and pondered which Batman tracked down a corporate criminal named Alfred the potential and possibilities of what could be. Bill suggested Stryker, who schemed to murder his two partners in the Apex Majestic and grandiose are the two terms by which I would Batman truly was. Like the Dark Knight, his influential and some adjustments and alterations inspired by the bat motif, Chemical Corporation before he would have to buy them out. personally describe the remarkable talent of maestro scribe, inspiring work has been mantled in the mists of mystery and which Bob incorporated into Batman’s unique and uncanny In the climatic scene, Batman punched Stryker so powerfully Gardner Francis Fox. For the most part, his life, his vast myth since the genesis of the character. For Gardner was image. Bob and Bill looked upon their collaborative effort and that the blow caused him to break through the protective railing mind-boggling body of work, and perhaps most importantly right there, front and center from nearly the very beginning, behold, Batman was very good! Bob presented Batman to and fall into a tank of acid. Finger’s second effort in Detec- of all, his immeasurable influence upon the wild and wacky taking over the script writing duties from Bill Finger as early as DC Comics’ senior editor Vincent A. -

Justice Society America!

Roy Thomas’ Star-Bedecked $ Comics Fanzine JUST WHEN YOU THOUGHT 8.95 YOU KNEW EVERYTHING THERE In the USA WAS TO KNOW ABOUT THE No.109 May JUSTICE 2012 SOCIETY ofAMERICA!™ 5 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 Art © DC Comics; Justice Society of America TM & © 2012 DC Comics. 6 Plus: SPECTRE & HOUR-MAN 2 8 Co-Creator 1 BERNARD BAILY Vol. 3, No. 109 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor AST! P.C. Hamerlinck AT L Comic Crypt Editor ALL IN Michael T. Gilbert FOR Editorial Honor Roll COLOR $8.95! Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Proofreader Rob Smentek Cover Artist Contents George Pérez Writer/Editorial: An All-Star Cast—Of Mind . 2 Cover Colorist Bernard Baily: The Early Years . 3 Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Ken Quattro examines the career of the artist who co-created The Spectre and Hour-Man. “Fairytales Can Come True…” . 17 Rob Allen Roger Hill The Roy Thomas/Michael Bair 1980s JSA retro-series that didn’t quite happen! Heidi Amash Allan Holtz Dave Armstrong Carmine Infantino What If All-Star Comics Had Sported A Variant Line-up? . 25 Amy Baily William B. Jones, Jr. Eugene Baily Jim Kealy Hurricane Heeran imagines different 1940s JSA memberships—and rivals! Jill Baily Kirk Kimball “Will” Power . 33 Regina Baily Paul Levitz Stephen Baily Mark Lewis Pages from that legendary “lost” Golden Age JSA epic—in color for the first time ever! Michael Bair Bob Lubbers “I Absolutely Love What I’m Doing!” . -

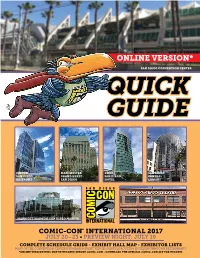

Online Version*

ONLINE VERSION* SAN DIEGO CONVENTION CENTER QUICK GUIDE HILTON MANCHESTER OMNI SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO GRAND HYATT SAN DIEGO CENTRAL BAYFRONT SAN DIEGO HOTEL LIBRARY MARRIOTT MARQUIS SAN DIEGO MARINA COMIC-CON® INTERNATIONAL 2017 JULY 20–23 • PREVIEW NIGHT: JULY 19 COMPLETE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • EXHIBITOR LISTS MAPS OF THE CONVENTION CENTER/PROGRAM & EVENT VENUES/SHUTTLE ROUTES & HOTELS/DOWNTOWN RESTAURANTS *ONLINE VERSION WILL NOT BE UPDATED BEFORE COMIC-CON • DOWNLOAD THE OFFICIAL COMIC-CON APP FOR UPDATES COMIC-CON INTERNATIONAL 2017 QUICK GUIDE WELCOME! to the 2017 edition of the Comic-Con International Quick Guide, your guide to the show through maps and the schedule-at-a-glance programming grids! Please remember that the Quick Guide and the Events Guide are once again TWO SEPARATE PUBLICATIONS! For an in-depth look at Comic- Con, including all the program descriptions, pick up a copy of the Events Guide in the Sails Pavilion upstairs at the San Diego Convention Center . and don’t forget to pick up your copy of the Souvenir Book, too! It’s our biggest book ever, chock full of great articles and art! CONTENTS 4 Comic-Con 2017 Programming & Event Locations COMIC-CON 5 RFID Badges • Morning Lines for Exclusives/Booth Signing Wristbands 2017 HOURS 6-7 Convention Center Upper Level Map • Mezzanine Map WEDNESDAY 8 Hall H/Ballroom 20 Maps Preview Night: 9 Hall H Wristband Info • Hall H Next Day Line Map 6:00 to 9:00 PM 10 Rooms 2-11 Line Map THURSDAY, FRIDAY, 11 Hotels and Shuttle Stops Map SATURDAY: 9:30 AM to 7:00 PM* 14-15 Marriott Marquis San Diego Marina Program Information and Maps SUNDAY: 16-17 Hilton San Diego Bayfront Program Information and Maps 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM 18-19 Manchester Grand Hyatt Program Information and Maps *Programming continues into the evening hours on 20 Horton Grand Theatre Program Information and Map Thursday through 21 San Diego Central Library Program Information and Map Saturday nights. -

Dossier Presse Musee Prive.Pdf

le musée de la bande dessinée présente exposition à Angoulême du 26 janvier au 6 mai 2012 vernissage le 26 janvier à 15 h en présence d’Art Spiegelman contact presse Pierre Laporte Communication 01 45 23 14 14 [email protected] [email protected] la Cité internationale de la bande dessinée et de l’image direction de la communication 05 45 38 65 52 [email protected] 05 17 17 31 03 [email protected] art spiegelman : le musée privé s o m m a i r e 2 a v a n t - p r o p o s par Gilles Ciment directeur général de la Cité internationale de la bande dessinée et de l’image 3 l e m u s é e p r i v é d ’ a r t s p i e g e l m a n 4 « m a c a r t o g r a p h i e p e r s o n n e l l e » par Art Spiegelman 6 l e p a r c o u r s d e l ’ e x p o s i t i o n 7 l e s a r t i s t e s r e p r é s e n t é s 8 l e s v i d é o s 9 l e s p r ê t e u r s 10 l e c o m m i s s a i r e d e l ’ e x p o s I t I o n 11 a r t s p i e g e l m a n 12 l a r é v o l u t i o n j u s t i n g r e e n 13 l e g é n é r i q u e d e l ’ e x p o s i t i o n 14 e n l i g n e s u r n e u v i e m e a r t 2 . -

From Pulp Hero to Superhero: Culture, Race, and Identity in American Popular Culture, 1900-1940 Julian C

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Faculty Publications 10-2008 From Pulp Hero to Superhero: Culture, Race, and Identity in American Popular Culture, 1900-1940 Julian C. Chambliss Rollins College, [email protected] William L. Svitavsky Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/as_facpub Part of the American Popular Culture Commons Published In Chambliss, Julian C., and William Svitavsky. 2008. From pulp hero to superhero: Culture, race, and identity in american popular culture, 1900-1940. Studies in American Culture 30 (1) (October 2008). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Pulp Hero to Superhero: Culture, Race, and Identity in American Popular Culture, 1900-1940 Adventure characters in the pulp magazines and comic books of the early twentieth century reflected development in the ongoing American fascination with heroic figures. 1 As the United States declared the frontier closed, established icons such as the cowboy became disconnected from everyday American experience and were supplanted by new popular adventure fantasies with heroes whose adventures stylized the struggle of the American everyman with a modern industrialized, heterogeneous world. The challenges posed by an urbanizing society to traditional masculinity, threatened to a weaken men’s physical and mental form and to disrupt the United States’ vigorous transformation from uncivilized frontier to modern society.2 Many middle-class social commentators embraced modern industrialization while warning against “sexless” reformers who sought to constrain modern society’s excesses through regulations design to prevent social exploitation, environmental spoilage, and urban disorder.