Digital Games and Beyond: What Happens When Players Compete?1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games

Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law Volume 18 Issue 3 Issue 3 - Spring 2016 Article 2 2015 Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games Julian Dibbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw Part of the Internet Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Julian Dibbell, Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games, 18 Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 419 (2021) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol18/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment & Technology Law by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT JOURNAL OF ENTERTAINMENT & TECHNOLOGY LAW VOLUME 18 SPRING 2016 NUMBER 3 Invisible Labor, Invisible Play: Online Gold Farming and the Boundary Between Jobs and Games Julian Dibbell ABSTRACT When does work become play and play become work? Courts have considered the question in a variety of economic contexts, from student athletes seeking recognition as employees to professional blackjack players seeking to be treated by casinos just like casual players. Here, this question is applied to a relatively novel context: that of online gold farming, a gray-market industry in which wage-earning workers, largely based in China, are paid to play fantasy massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) that reward them with virtual items that their employers sell for profit to the same games' casual players. -

Non-Serious Serious Games

Press Start Non-Serious Serious Games Non-Serious Serious Games Matthew Hudson Toshiba Design Center Abstract Serious games have been shown to promote behavioural change and impart skills to players, and non-serious games have proven to have numerous benefits. This paper argues that non-serious digital games played in a ‘clan’ or online community setting can lead to similar real world benefits to serious games. This paper reports the outcomes from an ethnographic study and the analysis of user generated data from an online gaming clan. The outcomes support previous research which shows that non-serious games can be a setting for improved social well- being, second language learning, and self-esteem/confidence building. In addition this paper presents the novel results that play within online game communities can impart benefits to players, such as treating a fear of public speaking. This paper ultimately argues that communities of Gamers impart ‘serious’ benefits to their members. Keywords Online communities; digital games; clan; social play; serious games; non-serious games Press Start 2016 | Volume 3 | Issue 2 ISSN: 2055-8198 URL: http://press-start.gla.ac.uk Press Start is an open access student journal that publishes the best undergraduate and postgraduate research, essays and dissertations from across the multidisciplinary subject of game studies. Press Start is published by HATII at the University of Glasgow. Hudson Non-Serious Serious Games Introduction Serious games have been shown to promote behavioural change and impart skills to players (Lampton et al. 2006, Wouters et al. 2009), and non-serious games have been shown to have numerous benefits (Granic et al. -

Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything

Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary Volume 31 Issue 1 Article 7 3-15-2011 Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything Alan Wilcox Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan Wilcox, Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything, 31 J. Nat’l Ass’n Admin. L. Judiciary Iss. 1 (2011) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj/vol31/iss1/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Regulating Violence in Video Games: Virtually Everything By Alan Wilcox* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. ....... 254 II. PAST AND CURRENT RESTRICTIONS ON VIOLENCE IN VIDEO GAMES ........................................... 256 A. The Origins of Video Game Regulation...............256 B. The ESRB ............................. ..... 263 III. RESTRICTIONS IMPOSED IN OTHER COUNTRIES . ............ 275 A. The European Union ............................... 276 1. PEGI.. ................................... 276 2. The United -

The Rise of Massively Multiplayer Online Games, Esports, And

The Rise of Massive Multiplayer Online Games, Esports, and Game Live Streaming An Interview with T. L.Taylor T. L.Taylor is Professor of Comparative Media Studies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and cofounder and Director of Research for AnyKey, an organization dedicated to supporting and developing fair and inclusive esports. She is a qualitative sociologist who has focused on internet and game studies for over two decades, and her research explores the rela- tions between culture and technology in online leisure environments. Her Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming (2018), which chronicled the emerging media space of online game broadcasting, won the 2019 American Sociological Association’s Communication, Information Technologies, and Media Sociology book award. She is also the author of Raising the Stakes: E-Sports and the Professionalization of Computer Gaming (2012) and Play between Worlds: Exploring Online Game Culture (2006), and coauthor of Ethnography and Virtual Worlds: A Handbook of Method (2012). Key words: assemblage; coconstruction; esports; Everquest; live streaming; MMOG; professional gaming; Twitch; video games American Journal of Play: Tell us how you played as a child? T. L.Taylor: My play was standard fare and fairly traditionally gendered, rooted in storytelling and imagination but also influenced by watching television. With stuffed animals and Barbie dolls, or just various outdoor spaces, I had a lot of material both for solo and social play. A lot of it was tied to favorite television characters we’d act out. I was also a huge fan of Viewmaster and enjoyed spending time “in” that stereographic space. -

Exergames and the “Ideal Woman”

Make Room for Video Games: Exergames and the “Ideal Woman” by Julia Golden Raz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christian Sandvig, Chair Professor Susan Douglas Associate Professor Sheila C. Murphy Professor Lisa Nakamura © Julia Golden Raz 2015 For my mother ii Acknowledgements Words cannot fully articulate the gratitude I have for everyone who has believed in me throughout my graduate school journey. Special thanks to my advisor and dissertation chair, Dr. Christian Sandvig: for taking me on as an advisee, for invaluable feedback and mentoring, and for introducing me to the lab’s holiday white elephant exchange. To Dr. Sheila Murphy: you have believed in me from day one, and that means the world to me. You are an excellent mentor and friend, and I am truly grateful for everything you have done for me over the years. To Dr. Susan Douglas: it was such a pleasure teaching for you in COMM 101. You have taught me so much about scholarship and teaching. To Dr. Lisa Nakamura: thank you for your candid feedback and for pushing me as a game studies scholar. To Amy Eaton: for all of your assistance and guidance over the years. To Robin Means Coleman: for believing in me. To Dave Carter and Val Waldren at the Computer and Video Game Archive: thank you for supporting my research over the years. I feel so fortunate to have attended a school that has such an amazing video game archive. -

Entertainment Software Rating Board - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Visited on 10/04/2016 Not Logged in Talk Contributions Create Account Log In

Entertainment Software Rating Board - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Visited on 10/04/2016 Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Entertainment Software Rating Board From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Contents "ESRB" redirects here. For the European financial agency, see European Systemic Risk Featured content Board. Current events "Mature content" redirects here. For other uses, see Pornography. Random article The Entertainment Software Rating Board Donate to Wikipedia Entertainment Software Rating Wikipedia store (ESRB) is a self-regulatory organization that Board assigns age and content ratings, enforces Interaction industry-adopted advertising guidelines, and Help About Wikipedia ensures responsible online privacy principles for Community portal computer and video games in the United States, Recent changes nearly all of Canada, and Mexico. The ESRB was Contact page established in 1994 by the Entertainment Software 2006 – present logo Tools Association (formerly the Interactive Digital What links here Software Association), in response to criticism of Type Non-profit, self-regulatory Related changes violent content found in video games such as Industry Organization and rating system Upload file Night Trap, Mortal Kombat, and other controversial Predecessor 3DO Rating System Special pages Recreational Software Advisory video games with excessively violent or sexual Permanent link Council content. Videogame Rating Council Page information September 16, 1994; 22 years Wikidata -

Independent Video Games and the Games ‘Indiestry’ Spectrum: Dissecting the Online Discourse of Independent Game Developers in Industry Culture By

Independent Video Games and the Games ‘Indiestry’ Spectrum: Dissecting the Online Discourse of Independent Game Developers in Industry Culture by Robin Lillian Haislett, B.S., M.A. A Dissertation In Media and Communication Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. Robert Moses Peaslee Chair of Committee Dr. Todd Chambers Dr. Megan Condis Dr. Wyatt Philips Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School December, 2019 Copyright 2019, Robin Lillian Haislett Texas Tech University, Robin Lillian Haislett, December 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is the result of the supremely knowledgeable Dr. Robert Moses Peaslee who took me to Fantastic Fest Arcade in 2012 as part of a fandom and fan production class during my doctoral work. This is where I met many of the independent game designers I’ve come to know and respect while feeling this renewed sense of vigor about my academic studies. I came alive when I discovered this area of study and I still have that spark every time I talk about it to others or read someone else’s inquiry into independent game development. For this, I thank Dr. Peaslee for being the catalyst in finding a home for my passions. More pertinent to the pages that follow, Dr. Peaslee also carefully combed through each malformed draft I sent his way, narrowed my range of topics, encouraged me to keep my sense of progress and challenged me to overcome challenges I had not previously faced. I feel honored to have worked with him on this as well as previous projects. -

Online Gaming an Introduction for Parents and Carers

allowing users to take part in leader boards, join group 1: An introduction to online gaming games or chat to others. Internet connectivity in a game Online gaming is hugely popular with children and young adds a new opportunity for gamers as it allows players people. Annual research conducted by OFCOM shows to find and play against, or with, other players. These that gaming is still one of the top activities enjoyed by may be their friends or family members or even other 5-16 year olds online, with many of them gaming via users in the game from around the world (in a multi- mobile devices and going online using their games player game). console. We know that parents and carers do have questions From sport related games to mission based games and and concerns about games, often about the type of quests inspiring users to complete challenges, games their child plays, who they may be speaking to interactive games cater for a wide range of interests, and for how much time their child is playing. and can enable users to link up and play together. This leaflet provides an introduction to online gaming Most games now have an online element to them; and advice for parents specifically related to gaming. Handheld Games: Handheld games are played on 2: Online gaming; how and where to play small portable consoles. As with other devices, There are many ways for users to play games online. This handheld games are also internet enabled. This includes free games found on the internet, games on allows gamers to download games, purchase additional smartphones, tablets and handheld consoles, as well as content, get new features and play and chat to other gamers. -

An Immersive Exergaming Platform to Promote Physical Activity in the Pediatric Population

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE iXercise: An Immersive Exergaming Platform to Promote Physical Activity in the Pediatric Population DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Networked Systems by Yunho Huh Dissertation Committee: Professor Magda El Zarki, Co-Chair Professor Shlomit Radom-Aizik, Co-Chair Professor Nalini Venkatasubramanian 2019 Portion of Chapter 1, 2, 3 © 2016 IEEE, Inc. Portion of Chapter 1, 2, 3 © 2018 IEEE, Inc. All other materials © 2019 Yunho Huh DEDICATION To god, my wife, my daughter, my parents and my dear friends for endless love and support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................ x CURRICULUM VITAE ............................................................................................................. xii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION ................................................................................ xiv 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Copyright Notice ............................................................................................................ -

General Trends in Multiplayer Online Games

World Applied Programming, Vol (3), Issue (1), January 2013. 1-4 ISSN: 2222-2510 ©2012 WAP journal. www.waprogramming.com General Trends in Multiplayer Online Games Masoud Nosrati * Ronak Karimi Kermanshah University of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran Kermanshah, Iran [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Online games are developed every day-to-day. Producing the games has become one of the most beneficial jobs for game studios. Different types of games with various aims are produced. But, among all of them, multiplayer games have a special place. A multiplayer video game is one which more than one person can play in the same game environment at the same time. In other hands, online games found the popularity between users. It provided an excellent opportunity for producing multiplayer online games. This paper will get into the general trends in multiplayer online games. So, the basic notions of gaming are talked as the first step. Then, Different general genres are introduced. Various types and impressive features of the genres are investigated in details, too. This paper tries to give a top level view to multiplayer online games to readers. Keyword: Online games, Massively multiplayer online game, Multiplayer online role-playing game, Multiplayer online battle arena I. INTRODUCTION An online game is a video game played over some form of computer network, using a personal computer or video game console [2]. There are many ways for users to play games online. This includes free games found on the internet, games on mobile phones and handheld consoles, as well as downloadable and boxed games on PCs and consoles such as the PlayStation, Nintendo Wii or Xbox. -

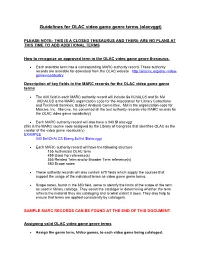

Guidelines for OLAC Video Game Genre Terms (Olacvggt)

Guidelines for OLAC video game genre terms (olacvggt) PLEASE NOTE: THIS IS A CLOSED THESAURUS AND THERE ARE NO PLANS AT THIS TIME TO ADD ADDITIONAL TERMS How to recognize an approved term in the OLAC video game genre thesaurus. • Each available term has a corresponding MARC authority record. These authority records are available for download from the OLAC website. http://olacinc.org/olac-video- game-vocabulary Description of key fields in the MARC records for the OLAC video game genre terms • The 040 field in each MARC authority record will include $a IlChALCS and $c Mvl (IlChALCS is the MARC organization code for the Association for Library Collections and Technical Services, Subject Analysis Committee. Mvl is the organization code for Marcive, Inc. Marcive, Inc converted all the text authority records into MARC records for the OLAC video game vocabulary) • Each MARC authority record will also have a 040 $f olacvggt (this is the MARC source code assigned by the Library of Congress that identifies OLAC as the creator of the video game vocabulary) EXAMPLE 040 $aIlChALCS $beng $cMvI $folacvggt • Each MARC authority record will have the following structure 155 Authorized OLAC term 455 Used For reference(s) 555 Related Term and/or Broader Term reference(s) 680 Scope notes • These authority records will also contain 670 fields which supply the sources that support the usage of the individual terms as video game genre terms. • Scope notes, found in the 680 field, serve to identify the limits of the scope of the term as used in library catalogs. They assist the cataloger in determining whether the term reflects the material they are cataloging and to what extent it does. -

How to Play the Game?

How to play the game? A study on MUD player types and their real life personality traits R.L.M. van Meurs, s395420 Master Thesis Leisure Studies Theme: Virtual Communities Supervisor: Drs. E.J. van Ingen Second Corrector: Dr. Ir. A. Bargeman Department of Social Sciences August 6th 2007, Tilburg Contents Contents II Abstract IV Preface V List of Abbreviations and MUD-related Concepts VII 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Laying Out the Research 2 1.1.1 Towards Different Playing Styles 3 1.1.2 Online versus Offline 4 1.2 Research Question, Goal and Relevance 5 2. Online Playing Styles and Offline Characteristics 7 2.1 Bartle’s Typology of Player Types 8 2.1.1 The Four Player Types 8 2.1.2 The Player Types Model and Dynamics 10 2.1.3 The Bartle Test 11 2.2 Criticism on Bartle’s Player Types 11 2.2.1 Yee’s Player Motivations 12 2.2.2 The Social versus Game-Like Debate 14 2.3 Alternative Ways of Categorizing Player Types and Motivations 15 2.3.1 Hierarchical Categorizations 16 2.3.2 Other Classifications 17 2.3.3 Relevance of Alternative Classifications 17 2.4 The Big Five / Offline Character Traits 18 2.4.1 Extraversion 19 2.4.2 Agreeableness 20 2.4.3 Conscientiousness 21 2.4.4 Emotional Stability 21 2.4.5 Intellect, Openness or Imagination 22 2.5 The Conceptual Model and Expectations 23 2.5.1 Summary of the Theory 23 2.5.2 The Conceptual Model and Expectations 24 II 3.