Final (Amended 06.07.2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Westminster Abbey 2013 Report to the Visitor Her Majesty the Queen

Westminster Abbey 2013 Report To The Visitor Her Majesty The Queen Your Majesty, The Dean and Chapter of the Collegiate Church of St Peter in Westminster, under the Charter of Queen Elizabeth I on 21st May 1560 and the Statutes graciously granted us by Your Majesty in a Supplemental Charter on 16th February 2012, is obliged to present an Annual Report to Your Majesty as our Visitor. It is our privilege, as well as our duty, now to present the Dean and Chapter’s Annual Report for the Year of Grace 2013. From time to time, the amount of information and the manner in which it is presented has changed. This year we present the report with more information than in recent years about the wide range of expertise on which the Dean and Chapter is able to draw from volunteers sitting on statutory and non-statutory advisory bodies. We also present more information about our senior staff under the Receiver General and Chapter Clerk who together ensure that the Abbey is managed efficiently and effectively. We believe that the account of the Abbey’s activities in the year 2013 is of wide interest. So we have presented this report in a format which we hope not only the Abbey community of staff, volunteers and regular worshippers but also the wider international public who know and love the Abbey will find attractive. It is our daily prayer and our earnest intention that we shall continue faithfully to fulfil the Abbey’s Mission: — To serve Almighty God as a ‘school of the Lord’s service’ by offering divine worship daily and publicly; — To serve the Sovereign by daily prayer and by a ready response to requests made by or on behalf of Her Majesty; — To serve the nation by fostering the place of true religion within national life, maintaining a close relationship with members of the House of Commons and House of Lords and with others in representative positions; — To serve pilgrims and all other visitors and to maintain a tradition of hospitality. -

The Tale of a Fish How Westminster Abbey Became a Royal Peculiar

The Tale of a Fish How Westminster Abbey became a Royal Peculiar For Edric it had been a bad week’s fishing in the Thames for salmon and an even worse Sunday, a day on which he knew ought not to have been working but needs must. The wind and the rain howled across the river from the far banks of that dreadful and wild isle called Thorney with some justification. The little monastic church recently built on the orders of King Sebert stood forlornly waiting to be consecrated the next day by Bishop Mellitus, the first Bishop of London, who would be travelling west from the great Minster of St Paul’s in the City of London. As he drew in his empty nets and rowed to the southern bank he saw an old man dressed in strange and foreign clothing hailing him. Would Edric take him across even at this late hour to Thorney Island? Hopeful for some reward, Edric rowed across the river, moaning to the old man about the poor fishing he had suffered and received some sympathy as the old man seemed to have had some experience in the same trade. After the old man had alighted and entered the little church, suddenly the building was ablaze with dazzling lights and Edric heard chanting and singing and saw a ladder of angels leading from the sky to the ground. Edric was transfixed. Then there was silence and darkness. The old man returned and admonished Edric for fishing on a Sunday but said that if he caste his nets again the next day into the river his reward would be great. -

A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

252 CATALOGUE OF MANUSCRIPTS [114 114. PARKER'S CORRESPONDENCE. \ ~, ' [ L . jT ames vac. Codex chartaceus in folio, cui titulus, EPISTOL^E PRINCIPUM. In eo autem continentur, 1. Epistola papae Julii II, ad Henricum VIII. in qua regem orat ut eum et sedem apostolicam contra inimicos defendat, data 14 Martii 1512, p. 4. 2. Henry VIII's recommendatory letter for Dr. Parker to be master of Corpus Christi College, dated Westminster ultimo Nov. anno regni 36°. original, p. 5. 3. Letter from queen Katherine [Parr] recommending Randall Radclyff to the bayliwick of the college of Stoke, dated Westm. 14 Nov. 36 Hen. VIII. p. 7. 4. Warrant for a doe out of the forest of Wayebrige under the sign manual of Henry VIII. dated Salisbury Oct. 13, anno regni 36, p. 8. 5. Letter from queen Elizabeth to the archbishop directing him to receive and entertain the French ambassador in his way to London. Richmond May 14, anno regni 6*°. p. 13. 6. From the same, commanding the archbishop to give his orders for a general prayer and fasting during the time of sickness, and requiring obedience from all her subjects to his directions, dated Richmond Aug. I, anno regni 5*°. p. 15. 7. From the same, directing the archbishop and other commissioners to visit Eaton-college, and to enquire into the late election of a provost, dated Lea 22 Aug. anno regni 3*°. p. 21. 8. Visitatio collegii de Eaton per Mattheum Parker archiepiscopum Cantuariensem, Robertum Home episcopum Winton et Anthonium Cooke militem, facta 9, 10 et 11 Sept. 1561, p. -

The King James Bible

Chap. iiii. The Coming Forth of the King James Bible Lincoln H. Blumell and David M. Whitchurch hen Queen Elizabeth I died on March 24, 1603, she left behind a nation rife with religious tensions.1 The queen had managed to govern for a lengthy period of almost half a century, during which time England had become a genuine international power, in part due to the stabil- ity Elizabeth’s reign afforded. YetE lizabeth’s preference for Protestantism over Catholicism frequently put her and her country in a very precarious situation.2 She had come to power in November 1558 in the aftermath of the disastrous rule of Mary I, who had sought to repair the relation- ship with Rome that her father, King Henry VIII, had effectively severed with his founding of the Church of England in 1532. As part of Mary’s pro-Catholic policies, she initiated a series of persecutions against various Protestants and other notable religious reformers in England that cumu- latively resulted in the deaths of about three hundred individuals, which subsequently earned her the nickname “Bloody Mary.”3 John Rogers, friend of William Tyndale and publisher of the Thomas Matthew Bible, was the first of her victims. For the most part, Elizabeth was able to maintain re- ligious stability for much of her reign through a couple of compromises that offered something to both Protestants and Catholics alike, or so she thought.4 However, notwithstanding her best efforts, she could not satisfy both groups. Toward the end of her life, with the emergence of Puritanism, there was a growing sense among select quarters of Protestant society Lincoln H. -

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey A SERVICE OF CELEBRATION TO MARK THE 400 TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE KING JAMES BIBLE Wednesday 16 th November 2011 Noon THE KING JAMES BIBLE AND TRUST ‘The Authorized Version provides a unique link between nations. It is a precious inheritance, worth every effort to preserve and to honour.’ His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales, Patron, King James Bible Trust The King James Bible Trust was established in 2007 to mark the King James Bible’s 400 th anniversary this year. Aptly described by Melvyn Bragg as ‘the DNA of the English language’, the King James Bible went with Britain’s emigrants as her colonies and trading networks became an Empire, so that now its coinages and cadences are heard wherever and however English is spoken. One glorious example: Dr Martin Luther King used its version of Isaiah chapter 40 verses 4–5 in his supreme speech: ‘I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low…’ This global importance has been reflected around the world over the past year. In the United States and in many Commonwealth countries there have been major symposia and conferences, with outstanding exhibitions featuring original 1611 Bibles. Church communities everywhere have celebrated the King James Bible with reading marathons, artistic displays, lectures, and commemorative services. For its own part the Trust has both tried to give as much publicity as possible to all this effort through its website, and itself instigated a press and publicity campaign. It has helped promote major lectures at Hampton Court Palace and Windsor Castle. -

The College and Canons of St Stephen's, Westminster, 1348

The College and Canons of St Stephen’s, Westminster, 1348 - 1548 Volume I of II Elizabeth Biggs PhD University of York History October 2016 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the college founded by Edward III in his principal palace of Westminster in 1348 and dissolved by Edward VI in 1548 in order to examine issues of royal patronage, the relationships of the Church to the Crown, and institutional networks across the later Middle Ages. As no internal archive survives from St Stephen’s College, this thesis depends on comparison with and reconstruction from royal records and the archives of other institutions, including those of its sister college, St George’s, Windsor. In so doing, it has two main aims: to place St Stephen’s College back into its place at the heart of Westminster’s political, religious and administrative life; and to develop a method for institutional history that is concerned more with connections than solely with the internal workings of a single institution. As there has been no full scholarly study of St Stephen’s College, this thesis provides a complete institutional history of the college from foundation to dissolution before turning to thematic consideration of its place in royal administration, music and worship, and the manor of Westminster. The circumstances and processes surrounding its foundation are compared with other such colleges to understand the multiple agencies that formed St Stephen’s, including that of the canons themselves. Kings and their relatives used St Stephen’s for their private worship and as a site of visible royal piety. -

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey A National Scout and Guide Service of Celebration and Thanksgiving Saturday 3rd November 2018 Noon HISTORICAL NOTE Following the death of The Chief Scout of the World, The Lord Baden-Powell OM GCMG GCVO KCB DL, in 1941, a memorial stone was unveiled in Westminster Abbey on 23rd April 1947. From then until 1955, Scouting Headquarters staff and some members held an annual wreathlaying and a small service in the Abbey. In 1957, the centenary of Baden-Powell’s birth, the service was attended by members of the Royal Family. In years thereafter it was referred to as a Service of Thanksgiving, and became a much bigger celebration. From 1959 onwards, the service was held on the nearest Saturday to 22nd February and from 1978, following the death of Lady Baden-Powell GBE the previous year, this annual service changed in style and name to a joint celebration of Thinking Day and Founder’s Day. In 1981, a memorial was dedicated to Lord and Lady Baden-Powell in Westminster Abbey. In 2011, the arrangements for the service were reviewed and changed in the light of increasing local opportunities to celebrate these special occasions. The current arrangement nevertheless maintains the tradition of the annual service at Westminster Abbey, now known as the National Scout and Guide Service of Celebration and Thanksgiving and focuses on thanking the adult volunteer leaders and supporters for their service and dedication. WESTMINSTER ABBEY We cannot say with certainty when Westminster Abbey was founded, but we know that around the year 960 Benedictine monks settled on the marshy north bank of the Thames, in a place called Thorney Island. -

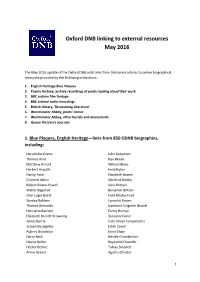

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens -

The World Loves a Lover: Monarchy, Mass Media, and the 1934 Royal Wedding of Prince George and Princess Marina∗

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository 1 All the World Loves a Lover: Monarchy, Mass Media, and the 1934 Royal Wedding of Prince George and Princess Marina∗ Edward Owens © Accepted for publication in The English Historical Review 2018 ∗ I am very grateful to Max Jones, Frank Mort, Penny Summerfield, David Cannadine, and James Greenhalgh for their comments on earlier drafts of this article. I would also like to thank Catherine Holmes and the anonymous readers of this journal for their suggestions. I have presented versions of this article at a number of conferences over the last couple of years: thank you to all of those who made insightful comments. I gratefully acknowledge the permission of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to quote from material in the Royal Archives, and thank Julie Crocker and staff for their help. Finally, I must thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council for funding the doctoral research on which this article is based. 2 A family on the throne is an interesting idea also. It brings down the pride of sovereignty to the level of petty life. No feeling could seem more childish than the enthusiasm of the English at the marriage of the Prince of Wales. They treated as a great political event, what, looked at as a matter of pure business, was very small indeed. But no feeling could be more like common human nature, as it is, and as it is likely to be. The women – one half the human race at least – care fifty times more for a marriage than a ministry. -

Spirituality, Shakespeare and Royalty

The Thirteenth ERIC SYMES ABBOTT Memorial Lecture delivered by Canon Eric James FKC at Westminster Abbey on Thursday the seventh of May, 1998 and subsequently at Keble College, Oxford The Eric Symes Abbott Memorial Trust was endowed by friends of Eric Abbott to provide for an annual lecture or course of lectures on spirituality. The venue for the lecture will vary between London, Oxford and Lincoln. The Trustees are: the Dean of King's College London (Chairman); the Dean of Westminster; the Warden of Keble College Oxford; the Very Reverend Dr Tom Baker; the Reverend John Robson and the Reverend Canon Eric James. ©1998 Eric James Published by The Dean’s Office, King’s College London Tel: (0171) 873 2333 Fax: (0171) 873 2344 2 Spirituality, Shakespeare and Royalty here are at least a dozen reasons why I have decided to take as my subject for this year’s Eric Symes Abbott Memorial Lecture Spirituality, Shakespeare and Royalty; and I’ve felt it right Tto spend some time at the beginning spelling out those reasons. The first is Eric Abbott’s own associations with the Monarchy. He was Chaplain to His Majesty King George VI from 1948 to 52 and to Her Majesty The Queen from 1952 to 59; and he prepared three royal princesses for their weddings here. He officiated at many other royal occasions, and was a much loved pastor to the Royal Family. In 1966, Eric was therefore made a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order. Secondly, on some memorable occasions, my own relationship with Eric involved, let us say, an oblique relationship to the Royal Family. -

Prominent Elizabethans. P.1: Church; P.2: Law Officers

Prominent Elizabethans. p.1: Church; p.2: Law Officers. p.3: Miscellaneous Officers of State. p.5: Royal Household Officers. p.7: Privy Councillors. p.9: Peerages. p.11: Knights of the Garter and Garter ceremonies. p.18: Knights: chronological list; p.22: alphabetical list. p.26: Knights: miscellaneous references; Knights of St Michael. p.27-162: Prominent Elizabethans. Church: Archbishops, two Bishops, four Deans. Dates of confirmation/consecration. Archbishop of Canterbury. 1556: Reginald Pole, Archbishop and Cardinal; died 1558 Nov 17. Vacant 1558-1559 December. 1559 Dec 17: Matthew Parker; died 1575 May 17. 1576 Feb 15: Edmund Grindal; died 1583 July 6. 1583 Sept 23: John Whitgift; died 1604. Archbishop of York. 1555: Nicholas Heath; deprived 1559 July 5. 1560 Aug 8: William May elected; died the same day. 1561 Feb 25: Thomas Young; died 1568 June 26. 1570 May 22: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1576. 1577 March 8: Edwin Sandys; died 1588 July 10. 1589 Feb 19: John Piers; died 1594 Sept 28. 1595 March 24: Matthew Hutton; died 1606. Bishop of London. 1553: Edmund Bonner; deprived 1559 May 29; died in prison 1569. 1559 Dec 21: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of York 1570. 1570 July 13: Edwin Sandys; became Archbishop of York 1577. 1577 March 24: John Aylmer; died 1594 June 5. 1595 Jan 10: Richard Fletcher; died 1596 June 15. 1597 May 8: Richard Bancroft; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1604. Bishop of Durham. 1530: Cuthbert Tunstall; resigned 1559 Sept 28; died Nov 18. 1561 March 2: James Pilkington; died 1576 Jan 23. 1577 May 9: Richard Barnes; died 1587 Aug 24. -

Friends Acquisitions 1964-2018

Acquired with the Aid of the Friends Manuscripts 1964: Letter from John Dury (1596-1660) to the Evangelical Assembly at Frankfurt-am- Main, 6 August 1633. The letter proposes a general assembly of the evangelical churches. 1966: Two letters from Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Nicholas of Lucca, 1413. Letter from Robert Hallum, Bishop of Salisbury concerning Nicholas of Lucca, n.d. 1966: Narrative by Leonardo Frescobaldi of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1384. 1966: Survey of church goods in 33 parishes in the hundreds of Blofield and Walsham, Norfolk, 1549. 1966: Report of a debate in the House of Commons, 27 February 1593. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Petition to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners by Miles Coverdale and others, 1565. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Correspondence and papers of Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885), Bishop of Lincoln. 1968: Letter from John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, to John Boys, 1599. 1968: Correspondence and papers of William Howley (1766-1848), Archbishop of Canterbury. 1969: Papers concerning the divorce of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. 1970: Papers of Richard Bertie, Marian exile in Wesel, 1555-56. 1970: Notebook of the Nonjuror John Leake, 1700-35. Including testimony concerning the birth of the Old Pretender. 1971: Papers of Laurence Chaderton (1536?-1640), puritan divine. 1971: Heinrich Bullinger, History of the Reformation. Sixteenth century copy. 1971: Letter from John Davenant, Bishop of Salisbury, to a minister of his diocese [1640]. 1971: Letter from John Dury to Mr. Ball, Preacher of the Gospel, 1639. 1972: ‘The examination of Valentine Symmes and Arthur Tamlin, stationers, … the Xth of December 1589’.