Intersectional Masculinity in Todrick Hall's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob the Drag Queen and Peppermint's Star Studded “Black Queer Town Hall”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BOB THE DRAG QUEEN AND PEPPERMINT’S STAR STUDDED “BLACK QUEER TOWN HALL” IS A REMINDER: BLACK QUEER PEOPLE GAVE US PRIDE Laverne Cox, Mj Rodriguez, Angelica Ross, Todrick Hall, Monet X Change, Isis King, Tiq Milan, Shea Diamond, Alex Newell, and Basit Among Participants NYC Pride and GLAAD to Support Three Day Virtual Event to Raise Funds for Black Queer Organizations and NYC LGBTQ Performers on June 19, 20, 21 New York, NY, Friday, June 12, 2020 – Advocates and entertainers Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen, today announced the “Black Queer Town Hall,” one of NYC Pride’s official partner events this year. NYC Pride and GLAAD, the global LGBTQ media advocacy organization, will stream the virtual event on YouTube and Facebook pages each day from 6:30-8pm EST beginning on Friday, June 19 and through Sunday, June 21, 2020. Performers and advocates slated to appear include Laverne Cox, Mj Rodriguez, Angelica Ross, Todrick Hall, Monet X Change, Isis King, Shea Diamond, Tiq Milan, Alex Newell, and Basit. Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen will host and produce the event. For a video featuring Peppermint and Bob the Drag Queen and more information visit: https://www.gofundme.com/f/blackqueertownhall The “Black Queer Town Hall” will feature performances, roundtable discussions, and fundraising opportunities for #BlackLivesMatter, Black LGBTQ organizations, and local Black LGBTQ drag performers. The new event replaces the previously announced “Pride 2020 Drag Fest” and will shift focus of the event to center Black queer voices. During the “Black Queer Town Hall,” a diverse collection of LGBTQ voices will celebrate Black LGBTQ people and discuss pathways to dismantle racism and white supremacy. -

Rupaul's Drag Race All Stars Season 2

Media Release: Wednesday August 24, 2016 RUPAUL’S DRAG RACE ALL STARS SEASON 2 TO AIR EXPRESS FROM THE US ON FOXTEL’S ARENA Premieres Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm Hot off the heels of one of the most electrifying seasons of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Mama Ru will return to the runway for RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 and, in a win for viewers, Foxtel has announced it will be airing express from the US from Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm on a new channel - Arena. In this second All Stars instalment, YouTube sensation Todrick Hall joins Carson Kressley and Michelle Visage on the judging panel alongside RuPaul for a season packed with more eleganza, wigtastic challenges and twists than Drag Race has ever seen. The series will also feature some of RuPaul’s favourite celebrities as guest judges, including Raven- Symone, Ross Matthews, Jeremy Scott, Nicole Schedrzinger, Graham Norton and Aubrey Plaza. Foxtel’s Head of Channels, Stephen Baldwin commented: “We know how passionate RuPaul fans are. Foxtel has been working closely with the production company, World of Wonder, and Passion Distribution and we are thrilled they have made it possible for the series to air in Australia just hours after its US telecast.” RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 will see 10 of the most celebrated competitors vying for a second chance to enter Drag Race history, and will be filled with plenty of heated competition, lip- syncing for the legacy and, of course, the All-Stars Snatch Game. The All Stars queens hoping to earn their place among Drag Race Royalty are: Adore Delano (S6), Alaska (S5), Alyssa Edwards (S5), Coco Montrese (S5), Detox (S5), Ginger Minj (S7), Katya (S7), Phi Phi O’Hara (S4), Roxxxy Andrews (S5) and Tatianna (S2). -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Picture Editing For A Structured Or Competition Program Alone Cold War August 16, 2018 Winter arrives in full force, testing the final participants like never before. Despite the elements, they’re determined to fight through the brutal cold, endless snow, and punishing hunger to win the $500,000 prize. While they all push through to their limits, at the end, only one remains. The Amazing Race Who Wants A Rolex? May 22, 2019 The Amazing Race makes a first ever trip to Uganda, where a massive market causes confusion and a labor intensive challenge on the shores of Lake Victoria exhausts teams before they battle in a Ugandan themed head-to-head competition ending in elimination. America's Got Talent Series Body Of Work May 28, 2018 Welcoming acts of any age and any talent, America’s Got Talent has remained the number one show of the summer for 13 straight seasons. American Idol Episode #205 March 18, 2019 Music industry legends and all-star judges Katy Perry, Lionel Richie and Luke Bryan travel the country between Los Angeles, New York, Denver and Louisville where incredibly talented hopefuls audition for a chance to win the coveted Golden Ticket to Hollywood in the search for the next American Idol. American Ninja Warrior Series Body Of Work July 09, 2018 American Ninja Warrior brings together men and women from all across the country, and follows them as they try to conquer the world’s toughest obstacle courses. Antiques Roadshow Ca' d'Zan, Hour 1 January 28, 2019 Antiques Roadshow transports audiences across the country to search for America’s true hidden treasure: the stories of our collective history. -

Carlie Craig Resume

CARLIE CRAIG SAG-AFTRA Hair Blonde Eyes Blue HT 5’1” WT 95 Vocal Range Mezzo Soprano TELEVISION Todrick Series Regular MTV First Impressions with Dana Carvey Guest Star USA Beyonce-thon: Break the Record Guest Star MTV Hit RECord on TV Guest Star/ Lead Vocalist Pivot OMG… We Should Have Eloped Guest Star TLC Dance Moms Vocalist Lifetime 2014 Kid’s Choice Awards Opening Vocalist Nickelodeon 2015 MTV Movie Awards Pre-Show Lead Dancer MTV NEW MEDIA #Bandcamp Principal Dir. Todrick Hall Mean Boyz Principal Dir. Todrick Hall Beauty and the Beat Boots Principal Dir. Todrick Hall Greasy Principal Dir. Marlon Wayans / Todrick Hall YouTube Adblitz with Jake and Amir Supporting Dir. Parker Seaman / Evan Scott THEATRE The Toddlerz Ball Principal Vocalist/Actor Todrick Hall World Tour Twerk Du Soleil Principal Vocalist/Actor Todrick Hall World Tour Chicago Roxie Hart Student Theatre Association If You Give a Mouse a Cookie Mouse Richard G. Fallon Theatre You’re a Good Man… Sally Brown Tallahassee Little Theatre Reefer Madness Mary Lane Augusta Conradi Studio Theatre High School Musical Sharpay Evans Douglas Theatre The Tortoise and the Hare Hedgehog Richard G. Fallon Theatre [title of show] Susan Lindsey Recital Hall MUSIC The Gemz, Girl Group Original Member/Vocalist Streetbeat Records TRAINING BA Theatre & Media Production Florida State University Stand-Up Pretty Funny Women with Lisa Sundstedt Improvisation The Groundlings with Jeff Galante, Invited Workshop with Wayne Brady UCB with Pam Murphy and Susannah Becket Sketch Writing UCB with Lee Rubenstein -

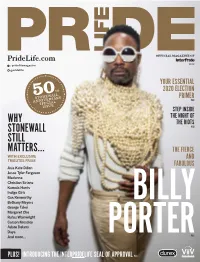

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

TODRICK HALL ABOUT a Multi-Talented Singer, Rapper, Actor, Director, Choreographer and Youtube Personality, Todrick Hall Rose to Prominence on American Idol

TODRICK HALL ABOUT A multi-talented singer, rapper, actor, director, choreographer and YouTube personality, Todrick Hall rose to prominence on American Idol. His popular YouTube channel has over 2.9 million subscribers and 588 million channel views, consisting notably of original songs, choreographed flash mobs for Beyonce, musical collaborations, and appearing regularly on RuPaul’s Drag Race as a guest judge. Hall distinguished himself as a Broadway star completing successful runs of 'Kinky Boots’ and 'Chicago'. Following two successful tours of 'Straight Outta Oz' - both of which were highly acclaimed by fans and critics alike - Hall visited 60 cities worldwide in his ‘The Forbidden Tour’ traveling the US, Europe, Asia, New Zealand, and Australia. With two groundbreaking visual albums under his belt - available for streaming via youtube/todrickhall - 2019 is set to be an action-packed year for Todrick Hall. HIGHLIGHTS • ‘Forbidden’ debuted at #1 on iTunes pop charts APPEARANCES HAS WORKED WITH • ‘Straight Outta Oz’ debuted at #2 on iTunes pop charts The VMAs Beyonce • Choreographing Beyonce’s ‘Blow’ music video The MTV Movie Awards Taylor Swift • Appearing in Taylor Swift’s ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ Kids Choice Awards RuPaul music video (1B+ views) The X Factor Ariana Grande • Headlining three International tours The Today Show Kendall and Kylie Jenner • Ru Paul’s Drag Race guest judge and choreographer So You Think You Can Dance Khloe Kardashian • Self-titled MTV show Dancing With The Stars Nicole Scherzinger • Biographical Documentary -

OUT North Texas 1825 Market Center Blvd Ste

THE EXPERIENCE A Complete Guide to Visiting DFW From TOP to BOTTOM THE SOURCE Our Dynamic Visitors and Relocation Guides THE CONNECTION A Comprehensive Business Directory THE COVER OUT Texas Actor | Singer | Dancer Todrick Hall OUTNT2017 2 3 OUTNT2017 4 2017 NT pain relief OUT wellnessNOW! done RIGHT! In Network with Cigna, BCBS, Aetna, United & more. State of the Art Physical Therapy & Hands on Care. Auto, Work & Sports Injuries. Neck & Back Pain. Bulging Disc Decompression. Yearsof service to our community. 304-time Winner Readers Voice Awards CEDAR SPRINGS CHIROPRACTICDr. Steven Tutt Clinical Director 4245 Cedar Springs Road (Between Douglas & Wycliff) www.drtuttdc.com • [email protected] Call or visit for a consultation 214.528.1900 5 OUTNT2017 OUTNT2017 6 7 2017 NT OUT Providing compassionate medical care in North Texas for more more than 25 Years! Peter Triporo, NP Comprehensive HIV/AIDS management Marc A. Tribble, M.D. STD testing and treatment Donald A. Graneto, M.D. David M. Lee, M.D. PrEP counseling and treatment Brady L. Allen, M.D. General adult medical care Eric Klappholz, NP Cosmetic - BOTOX® and Jason Vercher, PA JUVÉDERM® Uptown Physicians Group Uptown Tower, 4144 N. Central Expy Suite 750, Dallas, TX 75204 214-303-1033 www.UptownDocs.com New patients are currently being accepted. Most major insurances accepted. OUTNT2017 8 9 2017 NT RON ALLEN CPA, PC OUT • Former IRS Agent IRS Negotiations • Individual and Business Tax Returns • Accounting and Payroll Services • QuickBooks Pro Advisor On Staff First Consultation Free 2909 Cole Ave. Suite 119 Dallas, TX 75204 214.954.0042 [email protected] www.ronallencpa.com Gay owned and operated. -

Todrick Announces His Hall American Tour

Media Contact: Casey Blake 480-644-6620 [email protected] TODRICK ANNOUNCES HIS HALL AMERICAN WORLD TOUR Performing Live at Mesa Arts Center May 17 Tickets on sale Friday, December 15 Mesa, AZ (Dec. 13, 2017) – Broadway Actor and Streamy Award Winner Todrick Hall announced his new world tour Todrick Hall American: The Forbidden Tour. The tour will feature a brand new storyline with new songs, costumes, and production and will travel throughout North America, Europe, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand. The 50+ city tour will kick off March 29 in Ventura, CA at the Majestic Theatre with a stop at Mesa Arts Center on May 17. Tickets & VIP packages for the Hall American World Tour go on sale Friday, December 15. Todrick Hall fan club members may purchase tickets & VIP packages in advance beginning Wednesday, December 13. Visit www.TodrickHall.com for more info. [END] ABOUT TODRICK HALL Todrick is a singer, songwriter, dancer, actor, choreographer, costume designer, playwright and director. In 2010 Todrick Hall rose to fame as a semi-finalist on the ninth season of American Idol. He focused his talent on creating his own content on YouTube. His videos of flash mobs to songs by Ariana Grande and Beyoncé became viral video sensations. Todrick has amassed nearly 3 million YouTube subscribers and an astounding 513 million YouTube views. He has since choreographed for Beyoncé. He won the 2016 Streamy Award for Breakthrough Artist of the Year. In 2014, Todrick was named one of Forbes’ 30 Under 30 to watch in Hollywood & Entertainment. He also starred in his self-titled MTV show, TODRICK, which he wrote and directed. -

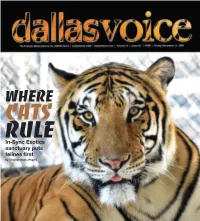

In-Sync Exotics Sanctuary Puts Felines First

Where cats rule In-Sync Exotics sanctuary puts felines first by Tammye Nash, Page 6 2 dallasvoice.com █ 12.11.20 CAROLE ANN BOYD, DDS, PC 12.11.20 | Volume 37 | Issue 31 Over 30 years of experience in toc GENERAL & COSMETIC DENTISTRY 10 headlines Welcoming JONATHAN VOGEL, DDS █ TEXAS NEWS 6 In-Sync: Refuge for exotic cats Call today 214.521.6261 10 Brandon Vance on leading Stonewall 4514 Cole Ave, Ste. 905 | DrBoyd.net █ LIFE+STYLE 16 On the road with Jenny Block IMMIGRATION Same-sex Couples and Individuals 20 Viola Davis stars in ‘Ma Rainey’ Green Cards ❖ Fiancè Visas ❖ Citizenship 16 ❖ ❖ Waivers Appeals Deportation Defense █ ON THE COVER Olinger Law, PLLC Odin, a 6-year-old Bengal tiger Lynn S. Olinger Board Certified Immigration Law Specailist rescued by In-Sync Exotics from a Serving the LGBT community for 15+ years Wisconsin breading center in 2014. 214.396.9090 ` Photo courtesy of In-Sync Exotics. www.Isolaw.com Design by Tammye Nash 14 departments SMILE with your EYES! 5 InstanTEA 21 Best Bets 6 News 22 Cassie Nova 14 Voices 24 Scene 16 Life+Style 26 Marketplace Award-winning Contact Lens Specialists Optometric Glaucoma Specialists • Therapeutic Optometrist 4414 Lemmon Ave. at Herschel Dallas, TX 75219 • 214.522-EYES doctoreyecare.com Dr. Allen B. Safir 12.11.20 █ dallasvoice 3 PET SUPPLIES PLUS® minus the hassle YOU CLICK, WE FETCH! FREE Curbside pickup in 2 hours $ offany ONLINE order of $30 or more Use Code 89409 at checkout Valid 12/31/20 online only! Excludes Acana, Fromm and Orijen products. -

Rupaul's Drag Race from Screens To

‘Tens, Tens, Tens Across the Board’: Representation, Remuneration, and Repercussion – RuPaul’s Drag Race from Screens to Streets Max Mehran A Thesis in The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montréal, Quebec, Canada January 2020 Ó Max Mehran, 2020 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Max Mehran Entitled: ‘Tens, Tens, Tens Across the Board’: Representation, Remuneration, and Repercussion – RuPaul’s Drag Race from Screens to Streets and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: ________________________________ Chair Luca Caminati ________________________________Examiner Haidee Wasson ________________________________Examiner Glyn Davis ________________________________Supervisor Kay Dickinson Approved by ________________________ Graduate Program Director Luca Caminati ________________________ Dean of Faculty Rebecca Duclos Date: January 20th, 2020 iii ABSTRACT ‘Tens, Tens, Tens Across the Board’: Representation, Remuneration, and Repercussion – RuPaul’s Drag Race from Screens to Streets Max Mehran Since its inception, RuPaul’s Drag Race (Drag Race) (2009-) has pitted drag queens against each other in a series of challenges testing acting, singing, and sewing skills. Drag Race continues to become more profitable and successful by the year and arguably shapes cultural ideas of queer performances in manifold ways. This project investigates the impacts of exploitative labour practices that emerge from the show, the commodification of drag when represented on screen, and how the show influences drag and queer performances off screen. -

The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS FOR THE 44th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Daytime Emmy Awards to be held on Sunday, April 30th Daytime Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Gala on Friday, April 28th New York – March 22nd, 2017 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards. The awards ceremony will be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Sunday, April 30th, 2017. The Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards will also be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Friday, April 28th, 2017. The 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations were revealed today on the Emmy Award-winning show, “The Talk,” on CBS. “The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences is excited to be presenting the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards in the historic Pasadena Civic Auditorium,” said Bob Mauro, President, NATAS. “With an outstanding roster of nominees, we are looking forward to an extraordinary celebration honoring the craft and talent that represent the best of Daytime television.” “After receiving a record number of submissions, we are thrilled by this talented and gifted list of nominees that will be honored at this year’s Daytime Emmy Awards,” said David Michaels, SVP, Daytime Emmy Awards. “I am very excited that Michael Levitt is with us as Executive Producer, and that David Parks and I will be serving as Executive Producers as well. With the added grandeur of the Pasadena Civic Auditorium, it will be a spectacular gala that celebrates everything we love about Daytime television!” The Daytime Emmy Awards recognize outstanding achievement in all fields of daytime television production and are presented to individuals and programs broadcast from 2:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m. -

44Th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations Were Revealed Today on the Emmy Award-Winning Show, “The Talk,” on CBS

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS FOR THE 44th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Daytime Emmy Awards to be held on Sunday, April 30th Daytime Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Gala on Friday, April 28th New York – March 22nd, 2017 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards. The awards ceremony will be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Sunday, April 30th, 2017. The Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards will also be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Friday, April 28th, 2017. The 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations were revealed today on the Emmy Award-winning show, “The Talk,” on CBS. “The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences is excited to be presenting the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards in the historic Pasadena Civic Auditorium,” said Bob Mauro, President, NATAS. “With an outstanding roster of nominees, we are looking forward to an extraordinary celebration honoring the craft and talent that represent the best of Daytime television.” “After receiving a record number of submissions, we are thrilled by this talented and gifted list of nominees that will be honored at this year’s Daytime Emmy Awards,” said David Michaels, SVP, Daytime Emmy Awards. “I am very excited that Michael Levitt is with us as Executive Producer, and that David Parks and I will be serving as Executive Producers as well. With the added grandeur of the Pasadena Civic Auditorium, it will be a spectacular gala that celebrates everything we love about Daytime television!” The Daytime Emmy Awards recognize outstanding achievement in all fields of daytime television production and are presented to individuals and programs broadcast from 2:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m.