An Actor Approaches Playing the Role of Feste, Shakespeare’S Update of the Lord of Misrule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Pack

Education Pack 1 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: Shakespeare and the Original Twelfth Night ..................................................... 4 William Shakespeare 1564 - 1616 ...................................................................................... 5 Elizabethan and Jacobean Theatre ..................................................................................... 6 Section 2: The Watermill’s Production of Twelfth Night .................................................. 10 A Brief Synopsis .............................................................................................................. 11 Character Map ................................................................................................................ 13 1920s and Twelfth Night.................................................................................................. 14 Meet the Cast ................................................................................................................. 16 Actor’s Blog .................................................................................................................... 20 Two Shows, One Set ........................................................................................................ 24 Rehearsal Diary ............................................................................................................... 26 Rehearsal Reports .......................................................................................................... -

Shakespeare and Contagion – Abstracts

SAA2015 – Seminar 37 – Shakespeare and Contagion – Abstracts Seminar Leaders: Mary Floyd-Wilson (University of North Carolina) and Darryl Chalk (University of Southern Queensland) Sabina Amanbayeva University of Delaware [email protected] “Falstaff’s Poisonous Affects: Politics and Physiology in 1 Henry IV” My paper is focused on the formation of intimacy through laughter in Shakespeare’s 1 Henry IV (1597). Using the framework of historical phenomenology and affect studies, I show how Falstaff’s jokes about his own body can actually be read as physiological manipulation and a political act. Early modern texts consistently associate the formation of illicit attachments with the work of poison and the subtle cunning of underworld figures. For instance, Thomas Dekker’s cony-catching pamphlets The Belman of London (1608) and Lanthorn and Candle-light (1608) take it as their guiding principle that cony-catchers commit their villanies through “breathes” and “vapours” that insidiously spread everywhere. A similar tactic, I argue, is at work in 1 Henry IV, where Falstaff’s jokes, called “vain comparatives” in the play, re-structure the relationship between the body and its environment by his successive spinning of new metaphors and thus new ways to imagine relations between self and other. The word-play between Hal and Falstaff becomes then a sort of titillation, playing with the body, as their mutual witticisms and jokes successively touch and re-touch each other’s contours. The essay contributes to the on-going conversation on affect and intimacy by bringing to the fore the physicality of early modern laughter and its ability to work like “poison” or contagious “vapour” in its creation of illicit intimacies. -

Phillips Phonograph : Vol. 23, No. 17 December 07, 1900

VOL. XXIII. PHILLIPS, MAINE, FRIDAY, DECEMBER 7, 1900. NO. 17. SPORTSMEN'S SUPPLIES SPORTSMEN’S SUPPLIES SPORTSMEN’S SUPPLIES SPO RTS M E N ’S SU P PLI ES OTTER WERE PLAYFUL, WHITE DEER AND B:G MOOSE. Dead Diver Region Game Rec Lake Austin Resort Shows Up U. n. C. UNIFORHITY. “ New Rival,” “Leader,” “Repeater.” ords Are Improving. Finely For Game. There are times when perfect ammunition is a necessity— not a luxury. Then the superior system of U. M. C. construc Snow Is Favorable For the Guide Who Never Returns to tion and loading proves itself a friend indeed. Camp Empty Handed. Hunters That Fome Late. American Shooting Records and Game Laws of the U. S. and Canada [Special correspondence to the Phonograph WINCHESTER [Special correspondence to the P honograph.] free fo r the asking. Bald Mountain Sporting i D e a d R i v e r , Nov. 27, 1900. Factory. Lodge, Nov., 27, 1900. j Union Factory Loaded Shotgun Shells. November is proving to be the banner The season of 1900 is drawing to a Bridgeport month for deer hunting and the game close with good results at the Lake “ New Rival” loaded with Black powders. “ Leader" records throughout the whole Dead Austin camps. The fishing has been Metallic Conn. River region are fast approaching those better than anticipated, and the hunters and “Repeater” loaded with Smokeless powders. Insist of former years. With the snowstorm have all secured their deer, while three A gency upon having them, take no others, and you will get the of Saturday night and all day Sunday, moose have been taken by local hunters, Cartridge Tim Clark, one of the Lake Austin 313 Broadway, deer will be a sure thing for every man best shells that money can buy. -

The Fools of Shakespeare's Romances

Sede Amministrativa: Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari (DISLL) SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN: Scienze Linguistiche, Filologiche e Letterarie INDIRIZZO: Filologie e Letterature Classiche e Moderne CICLO XXVI “Armine... thou art a foole and knaue”: The Fools of Shakespeare’s Romances Direttore della Scuola : Ch.ma Prof.ssa Rosanna Benacchio Supervisore : Ch.ma Prof.ssa Alessandra Petrina Dottoranda : Alice Equestri Abstract La mia tesi propone un’analisi dettagliata dei personaggi comici nei romances Shakespeariani (Pericles, Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale e The Tempest) in particolare quelli creati appositamente per Robert Armin, attore comico di punta dei King’s Men in quel periodo. Nel primo capitolo traccio la presenza di Armin nei quattro testi, individuando cioè gli indizi che rimandano alla sua figura e alla tipologia di comicità tipica dei suoi personaggi precedenti in Shakespeare e di quelli presenti nelle sue stesse opere. I quattro personaggi creati per lui da Shakespeare vengono analizzati in profondità nei seguenti capitoli, raggruppandoli a seconda dei loro ruoli sociali o professioni. Nel secondo capitolo mi occupo dei fools criminali, considerando Pericles e The Winter’s Tale, dove i personaggi di Boult e Autolycus sono rispettivamente un ruffiano di bordello e un delinquente di strada. Nel terzo capitolo mi concentro invece sui personaggi che esibiscono o vengono discriminati per una reale od imputata deficienza congenita (natural folly): il principe Cloten in Cymbeline e Caliban in The Tempest. Per ciascun caso discuto il rapporto del personaggio con le fonti shakespeariane ed eventualmente con la tradizione comica precedente o contemporanea a Shakespeare, il ruolo all’interno del testo, e il modo in cui il personaggio suscita l’effetto comico. -

A Distinctive BBC

A distinctive BBC April 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 1. Executive Summary 2. What is distinctiveness 3. Measuring distinctiveness today – what the audience thinks 4. Measuring distinctiveness today – comparisons to other services 5. Enhancing distinctiveness in the future 2 FOREWORD I believe that the case for the BBC is a very straightforward, pragmatic one. We have produced, and continue to produce, some of the very best programmes and services in the world. That is why people like the BBC. That is why they enjoy it. That is why they trust it. That is why they value it. That is what they pay us to do. If the BBC stands for anything, it stands for quality. In just the last month, we have seen Panorama’s exposé of the Panama Papers; Radio 4’s previously unseen footage of Kim Philby speaking to the Stasi; the domestic abuse storyline on The Archers; Inside Obama’s White House and Behind Closed Doors; The Night Manager, Undercover and Cuckoo. We have just launched the 2016 BBC Proms. And those are just a few highlights. This is the BBC I believe in. A beacon of cultural excellence in a world increasingly awash with media of all kinds. A trusted voice in a crowded arena, accountable to the public and focused on their interests, independent of both government and market. A benchmark of quality. But the unique way the BBC is funded places two further obligations on us. Because the BBC’s funding is independent, that gives us creative freedom. That means a BBC that must be more prepared than ever to take risks. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

3448 Shakespeare Comedies

DOST THOU THINK, BECAUSE THOU ART VIRTUOUS, THERE SHALL BE NO MORE CAKES AND ALE? —Twelfth Night, 2.3.106–107 Unit 1—Lesson 1 Twelfth Night INTRODUCTION You’re probably familiar with the Christmas carol “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” These twelve days refer to the twelve days after Christmas, and particularly the twelfth day, which in myth (not in the Bible) is the day when the Magi first saw Jesus. This day (January 6) is also called Epiphany (which means “manifestation”). Shakespeare probably wrote Twelfth Night for an Epiphany celebration; you should not take the title as referring in any way to when the play is set or the passage of time in the play. Although the title does not refer to the setting, in Twelfth Night characters do have revelations or epiphanies. Another reason the title is fitting is that in Elizabethan England, Epiphany was a day of festivals and celebrations. The mood of Twelfth Night is celebratory, and one of the themes of the play is to assert the fundamental goodness of celebration and festival. Those who would interfere with such happiness are either converted from their position or dealt with harshly. WHILE YOU READ Here are some questions to consider while reading the play: What types of love are shown? Who is having fun and who isn’t? Who hides or disguises themselves in some way? Who speaks in prose and who speaks in blank verse? Why do you think that is? 39 Lightning Literature and Composition—Shakespeare: Comedies and Sonnets PLOT SUMMARY 1.1 The duke is pining away for Olivia, who is in mourning for her brother. -

What Size Viola?

From Violins and Violinists December 1943 What Size Viola? VIOLA EXPERIMENTA By Robert Dolejsi When the Violin finally reached her destiny in the ideal instrument that knows no peer today, and was recognized as the stringed mistress of the soprano family, it fell to the unfortunate lot of that hapless maiden Viola to become the subject of avid experimentation. In their search for an instrument of identical design and superb characteristics, makers, luthiers, artisans and, (indirectly through suggestion) composers and players, conducted intense experiments to find a medium of deeper register that would represent the alto and tenor voice and thus complete the quartet of strings. There is ample ground in all instrumental bibliography to support the theory that experimentation was one of the chief causes for the numerous sizes in fiddles that marked instrument making in the viola category from the 17th century onward. That generic English term Viol designated the instrument that succeeded the medieval fiddle. In literature at least, though not in actual invention, it preceded the violin family; for it must be emphasized that contrary to general conception, the viol was more the precursor and not the predecessor or direct ancestor of the violin. This distinction in progenitorship belongs to that branch of the instrumental tree represented by the rebec and Iyra—and all three branches were growing and developing simultaneously side by side. The experimental premise had already been laid in the highly variegated family of viols. Oddly enough, and paradoxically too, it appears that the viola or tenor ( the names were interchangeable during a period when great confusion in sizes and types existed ), was the first of the viol family to adopt changes in tuning and string number. -

Notes on the Bacon-Shakespeare Question

NOTES ON THE BACON-SHAKESPEARE QUESTION BY CHARLES ALLEN BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY ftiucrsi&c press, 1900 COPYRIGHT, 1900, BY CHARLES ALLEN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED GIFT PREFACE AN attempt is here made to throw some new light, at least for those who are Dot already Shakespearian scholars, upon the still vexed ques- tion of the authorship of the plays and poems which bear Shakespeare's name. In the first place, it has seemed to me that the Baconian ar- gument from the legal knowledge shown in the plays is of slight weight, but that heretofore it has not been adequately met. Accordingly I have en- deavored with some elaboration to make it plain that this legal knowledge was not extraordinary, or such as to imply that the author was educated as a lawyer, or even as a lawyer's clerk. In ad- dition to dealing with this rather technical phase of the general subject, I have sought from the plays themselves and from other sources to bring together materials which have a bearing upon the question of authorship, and some of which, though familiar enough of themselves, have not been sufficiently considered in this special aspect. The writer of the plays showed an intimate M758108 iv PREFACE familiarity with many things which it is believed would have been known to Shakespeare but not to Bacon and I have to collect the most '; soughtO important of these, to exhibit them in some de- tail, and to arrange them in order, so that their weight may be easily understood and appreci- ated. -

Twelfth Night KEY CHARACTERS and SENSORY MOMENTS

Twelfth Night KEY CHARACTERS AND SENSORY MOMENTS Characters Viola Sebastian Olivia Malvolio Sir Andrew Sir Toby Feste Maria Orsino Antonio Sensory Moments Below is a chronological summary of the key sensory moments in each act and scene. Latex balloons are used onstage throughout the show. Visual, dialogue or sound cues indicating dramatic changes in light, noise or movement are in bold. PRESHOW • A preshow announcement plays over the loudspeaker and instruments tune onstage. ACT ONE SCENE ONE SENSORY MOMENTS • Feste begins to sing a song. When he puts DESCRIPTION a paper ship in the water, the storm begins. At Duke Orsino’s palace in Illyria, Cesario and There is frequent loud thunder, flickering others sing for Orsino. He’s in love with the lights and flashes of lightning via strobe countess Olivia, but it’s unrequited because she lights. Actors shout during the turmoil, is in mourning for her brother and won’t receive cymbals crash and drums rumble. his messengers. • The storm sequence lasts about 90 seconds. • After the storm, lights slowly illuminate SENSORY MOMENTS the stage. • Actors begin singing a song. Orsino enters the stage and picks up a balloon. When he walks to the center of the stage, the balloon SCENE TWO pops loudly. • When Orsino says, “Love-thoughts lie rich DESCRIPTION when canopied with bowers,” the actors Viola washes ashore in Illyria, saved by the leave the stage, suspenseful music plays and ship’s captain. She asks the captain to help her the lights go dark. disguise herself so she can get work in Orsino’s court. -

Grotesque Transformations and the Discourse of Conversion in Robert Greene's Works and Shakespeare's Falstaff

Grotesque Transformations and the Discourse of Conversion in Robert Greene's Works and Shakespeare's Falstaff Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors DiRoberto, Kyle Louise Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 08:47:04 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/203437 GROTESQUE TRANSFORMATIONS AND THE DISCOURSE OF CONVERSION IN ROBERT GREENE'S WORK AND SHAKESPEARE'S FALSTAFF by Kyle DiRoberto _____________________ Copyright © Kyle DiRoberto A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2011 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Kyle DiRoberto entitled Grotesque Transformations and the Discourse of Conversion in Robert Greene's Work and Shakespeare's Falstaff. and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/8/11 Dr. Meg Lota Brown _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/8/11 Dr. Tenney Nathanson _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/8/11 Dr. Carlos Gallego Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

DR. CLARK's FIRST LETTER to DR. DUVAL Unanswerable, a Thing Which No One Has Undertaken As Yet

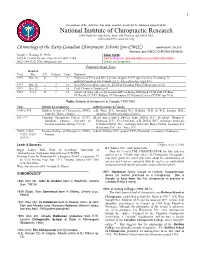

1 Preparation of the data base was made possible in part by the financial support of the National Institute of Chiropractic Research 2950 North Seventh Street, Suite 200, Phoenix AZ 85014 USA (602) 224-0296; www.nicr.org Chronology of the Early Canadian Chiropractic Schools (pre-CMCC) word count: 25,213 filename: pre-CMCC CHRONO 03/06/28 Joseph C. Keating, Jr., Ph.D. Color Code: 6135 N. Central Avenue, Phoenix AZ 85012 USA Red & Magenta: questionable or uncertain information (602) 264-3182; [email protected] Green: for emphasis Fountain Head News Month & Year Day A.C. Volume Issue Comment 1917 Nov 10 23 7 9 "Expense of UCA and PSC Lyceum, August, 1917" (pp 2-3); New Zealand (p 7); military/Canada (p 10); Canada (p 12); Chiro Directory (pp 13-5) 1917 Dec 15 -- 7 14 list of DCs in military (pp 1-2); E DuVal/Canadian Chiro College (pp 12-15) 1917 Dec 22 -- 7 15 Cecil Clemmer/Canada (p 4) 1918 Feb 2 23 7 21 critique of chiro colleges by Toronto MD, including Pittsburgh CC/St Paul CC/Ross CC/Pacific CC/UCC/Indiana CC/Davenport CC/National/Carver CC/PSC (pp 7-15) Table: Schools of chiropractic in Canada, 1909-1928 Year School & Location(s) Administration & Faculty 1909-c1914 Robbins School of Chiropractic (RSC), A.B. West, D.C. recruited W.J. Robbins, M.D. & W.E. Lemon, M.D.; Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario (alumnus Henderson bought charter) 1914-??? Canadian Chiropractic College (CCC), (Henderson recruited DuVal); Ernst DuVal, D.C., President; Thomas E. Hamilton, Ontario, relocated to Patterson, D.C., Vice-President; A.R.