Life in London's Eastern Suburb, C. 1550—C. 1700 Philip Baker I'd Like to Begin with a Quotation from the London Chronicle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central London Plan Bishopsgate¬Corridor Scheme Summary

T T T T D S S S R Central London Plan EN H H H H H RE G G BETHNAL SCLATER S Bishopsgate¬corridor Scheme Summary I T H H ShoreditchShoreditch C Key T I HHighigh StreetStreet D E Bus gate – buses and cyclists only allowed R O B through during hours of operation B H R W R OR S I I Q Q SH C IP C S K Section of pavement widened K ST N T E Y O S T L R T A L R G A U Permitted turns for all vehicles DPR O L I N M O B L R N O F S C O E E S P ST O No vehicular accessNSN except buses P M I A FIF E M Email feedback to: T A E streetspacelondon@tfl.gov.uk G R S C Contains Ordnance Survey data LiverpoolLiverpool P I © Crown copyright 2020 A SStreettreet O L H E MoorgateM atete S ILL S T I ART E A B E T RY LANAN R GAG E R E O L M T OOO IVE * S/BS//B onlyoonlyy RP I OO D M L S O T D S LO * N/BN//B onlyoonlyy L B ND E S O ON S T RNR W N E A E LL X T WORM A WO S OD HOUH T GATEG CA T T M O R S R E O U E H S M NDN E G O T I T I A LE D H O D S S EL A G T D P M S B I A O P E T H R M V C . -

Broad Street Ward News

Broad Street:Broad Street 04/06/2013 12:58 Page 1 BROAD STREET BROADSHEET JUNE 2013 COMMUNICATING WITH THOSE WHO LIVE AND WORK IN THE CITY OF LONDON THE NEW CIVIC TEAM FOR BROAD STREET After a very hard fought election in March, when six candidates contested the three seats on the Court of Common Council, a new civic team now represents the Ward of Broad Street. John Bennett and John Scott were re-elected and are joined by Chris Hayward, all of whom have very strong links with the Ward through work and residence. In this edition we provide short profiles of the Common Councilmen and give their responsibilities for the coming term. John Bennett graduated in biochemistry from Christ Church, Oxford in 1967 and qualified as a Chartered Accountant with Arthur Andersen. He then spent the next 35 years in various roles in International Banking in London and Jersey with Citibank and Hill Samuel. During this time he developed a keen interest in Compliance and Regulation. He retired from Deutsche Bank in 2005 after serving as Director of Compliance and UK Money Laundering Reporting Officer. John is Deputy for the Ward and has represented the electors of Broad Street L to R: Chris Hayward CC, Deputy John Bennett, John Scott CC for the last eight years. He currently Ward Club. He is a Trustee of the Lord Bank, for over thirty years until he retired serves on the Port Health & Mayor’s 800th Anniversary Awards Trust, at the grand old age of 55. In his capacity Environmental Services Committee and established by the late Sir Christopher as Global Head of Public Sector Finance it the Community & Children’s Services Collett, late Alderman for the Ward, seemed logical to accept the suggestion Committee and in 2010 was elected to during his mayoral year, and a Trustee of of standing as an elected Member in 1998 serve on the Policy & Resources charities related to the Ward’s parish and ever since then he has represented Committee, the most senior committee church, St Margaret Lothbury. -

St. Margaret's in Eastcheap

ST. MARGARET'S IN EASTCHEAP NINE HUNDRED YEARS OF HISTORY A Lecture delivered to St. Margaret's Historical Society on January 6th, 1967 by Dr. Gordon Huelin "God that suiteth in Trinity, send us peace and unity". St. Margaret's In Eastcheap : Nine hundred years of History. During the first year of his reign, 1067, William the Conqueror gave to the abbot and church of St. Peter's, Westminster, the newly-built wooden chapel of St. Margaret in Eastcheap. It was, no doubt, with this in mind that someone caused to be set up over the door of St. Margaret Pattens the words “Founded 1067”. Yet, even though it seems to me to be going too far to claim that a church of St. Margaret's has stood upon this actual site for the last nine centuries, we in this place are certainly justified in giving' thanks in 1967 for the fact that for nine hundred years the faith has been preached and worship offered to God in a church in Eastcheap dedicated to St. Margaret of Antioch. In the year immediately following the Norman Conquest much was happening as regards English church life. One wishes that more might be known of that wooden chapel in Eastcheap, However, over a century was to elapse before even a glimpse is given of the London churches-and this only in general terms. In 1174, William Fitzstephen in his description of London wrote that “It is happy in the profession of the Christian religion”. As regards divine worship Fitzstephen speaks of one hundred and thirty-six parochial churches in the City and suburbs. -

John Leland's Itinerary in Wales Edited by Lucy Toulmin Smith 1906

Introduction and cutteth them out of libraries, returning home and putting them abroad as monuments of their own country’. He was unsuccessful, but nevertheless managed to John Leland save much material from St. Augustine’s Abbey at Canterbury. The English antiquary John Leland or Leyland, sometimes referred to as ‘Junior’ to In 1545, after the completion of his tour, he presented an account of his distinguish him from an elder brother also named John, was born in London about achievements and future plans to the King, in the form of an address entitled ‘A New 1506, probably into a Lancashire family.1 He was educated at St. Paul’s school under Year’s Gift’. These included a projected Topography of England, a fifty volume work the noted scholar William Lily, where he enjoyed the patronage of a certain Thomas on the Antiquities and Civil History of Britain, a six volume Survey of the islands Myles. From there he proceeded to Christ’s College, Cambridge where he graduated adjoining Britain (including the Isle of Wight, the Isle of Man and Anglesey) and an B.A. in 1522. Afterwards he studied at All Souls, Oxford, where he met Thomas Caius, engraved map of Britain. He also proposed to publish a full description of all Henry’s and at Paris under Francis Sylvius. Royal Palaces. After entering Holy Orders in 1525, he became tutor to the son of Thomas Howard, Sadly, little or none of this materialised and Leland appears to have dissipated Duke of Norfolk. While so employed, he wrote much elegant Latin poetry in praise of much effort in seeking church advancement and in literary disputes such as that with the Royal Court which may have gained him favour with Henry VIII, for he was Richard Croke, who he claimed had slandered him. -

Chaucer’S Birth—A Book Went Missing

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. •CHAPTER 1 Vintry Ward, London Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience. — James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man In the early 1340s, in Vintry Ward, London— the time and place of Chaucer’s birth— a book went missing. It wasn’t a very important book. Known as a ‘portifory,’ or breviary, it was a small volume containing a variety of excerpted religious texts, such as psalms and prayers, designed to be carried about easily (as the name demonstrates, it was portable).1 It was worth about 20 shillings, the price of two cows, or almost three months’ pay for a carpenter, or half of the ransom of an archer captured by the French.2 The very presence of this book in the home of a mer- chant opens up a window for us on life in the privileged homes of the richer London wards at this time: their inhabitants valued books, ob- jects of beauty, learning, and devotion, and some recognized that books could be utilized as commodities. The urban mercantile class was flour- ishing, supported and enabled by the development of bureaucracy and of the clerkly classes in the previous century.3 While literacy was high in London, books were also appreciated as things in themselves: it was 1 Sharpe, Calendar of Letter- Books of the City of London: Letter- Book F, fol. -

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

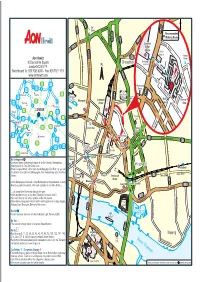

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

Cutlers Court, 115 Houndsditch, London, EC3A 7BR 2,345 to 9,149 Sq Ft

jll.co.uk/property To Let Cutlers Court, 115 Houndsditch, London, EC3A 7BR 2,345 to 9,149 sq ft • Cost effective fitted out offices • Furniture packages available • Flexible working space • Manned reception Location EPC The building is located on the north side of Houndsditch. 115 This property has been graded as E (122). Houndsditch benefits from excellent access to public transport being 3 minutes from Liverpool Street station, 4 minutes from Rent Aldgate tube station and 8 minutes from Bank Station. The £19.50 per sq ft property is situated within close proximity to Lloyd’s of London exclusive of rates, service charge and VAT (if applicable). and Broadgate and is moments from the amenities of Devonshire Square and Spitalfields. Business Rates Rates payable: £14.77 per sq ft Specification The Ground and 4th floors are available with high quality fit Service Charge outs in situ as follows: £11.85 per sq ft Ground floor EC3A 7BR - 1 x 8 person meeting room - 1 x 6 person meeting room - 1 x 4 person meeting room - Kitchen/breakout area - Cat 6 Data Cabling 4th floor - 1 x 10 person meeting room - 2 x 8 person meeting rooms - 2 on floor showers - Kitchen/breakout area - New floor outlet boxes and underfloor CAT 6 data cabling Terms New lease available from the Landlord (term certain until June Contacts 2023). Nick Lines 0207 399 5693 Viewings [email protected] Viewing via the sole agents only. Nick Going Accommodation [email protected] Floor/Unit Sq ft Rent Availability 4th 6,804 £19.50 per sq ft Available Ground 2,345 £19.50 per sq ft Available Total 9,149 JLL for themselves and for the vendors or lessors of this property whose agents they are, give notice that:- a. -

861 Sq Ft Headquarters Office Building Your Own Front Door

861 SQ FT HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDING YOUR OWN FRONT DOOR This quite unique property forms part of the building known as Rotherwick House. The Curve comprises a self-contained building, part of which is Grade II Listed, which has been comprehensively refurbished to provide bright contemporary Grade A office space. The property — located immediately to the east of St Katharine’s Dock and adjoining Thomas More Square — benefits from the immediate area which boasts a wide variety of retail and restaurant facilities. SPECIFICATION • Self-contained building • Generous floor to ceiling heights • New fashionable refurbishment • Full-height windows • New air conditioning • Two entrances • Floor boxes • Grade II Listed building • LG7 lighting with indirect LED up-lighting • Fire and security system G R E A ET T THE TEA TRE E D S A BUILDING OL S T E R SHOREDITCH N S HOUSE OLD STREET T R E E T BOX PARK AD L RO NWEL SHOREDITCH CLERKE C I HIGH STREET T Y R G O O A S D W S F H A O E R L U A L R T AD T H I O R T R N A S STEPNEY D’ O O M AL G B N A GREEN P O D E D T H G O T O WHITECHAPEL A N N R R R O D BARBICAN W O CHANCERY E A FARRINGDON T N O LANE D T T E N H A E M C T N O C LBOR A D O HO M A IGH MOORGATE G B O H S R R U TOTTENHAM M L R LIVERPOOL P IC PE T LO E COURT ROAD NDON WA O K A LL R N R H STREET H C L C E E O S A I SPITALFIELDS I IT A A W B N H D L E W STE S R PNEY WAY T O J R U SALESFORCE A E HOLBORN B T D REE TOWER E ST N I D L XFOR E G T O W R E K G ES H ALDGATE I A H E N TE A O M LONDON MET. -

![Download/Chb/MESBD/MESBD.Zip [Last Accessed August 4, 2011]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8841/download-chb-mesbd-mesbd-zip-last-accessed-august-4-2011-608841.webp)

Download/Chb/MESBD/MESBD.Zip [Last Accessed August 4, 2011]

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 10 March 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Kendall, E. and Montgomery, J. and Evans, J. and Stantis, C. and Mueller, V. (2013) 'Mobility, mortality, and the middle ages : identication of migrant individuals in a 14th century black death cemetery population.', American journal of physical anthropology., 150 (2). pp. 210-222. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22194 Publisher's copyright statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: Kendall, E.J., Montgomery, J., Evans, J.A., Stantis, C. and Mueller, V. (2013), Mobility, mortality, and the middle ages: Identication of migrant individuals in a 14th century black death cemetery population. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 150 (2): 210-222, which has been published in nal form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22194. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. -

RDP SPEC GUIDE 09.Pdf

Flora London Marathon 2009 Pace Chart Mile Elite Wheel Wheel Elite 3:30 4:30 5:00 6:00 Women chair chair Men/ Pace Pace Pace Pace Spectator Men Women Mass Start 09:00 09:20 09:20 09:45 09:45 09:45 09:45 09:45 1 09:05 09:23 09:24 09:49 09:53 09:55 09:56 09:58 Guide 2 09:10 09:27 09:28 09:54 10:01 10:05 10:07 10:12 Flora London Marathon spectators are a crowd on the move! Most people like to try 3 09:15 09:31 09:32 09:59 10:09 10:15 10:19 10:26 and see runners at more than one location on the route and it’s great to soak up the 4 09:21 09:34 09:36 10:04 10:17 10:26 10:30 10:40 atmosphere, take in some of the landmarks, and perhaps pick up refreshments on 5 09:26 09:38 09:41 10:09 10:25 10:36 10:42 10:53 the way too. Here are some tips on getting around London to make your day safer 6 09:31 09:42 09:45 10:13 10:33 10:46 10:53 11:07 and more enjoyable. 7 09:36 09:45 09:49 10:18 10:41 10:57 11:05 11:21 8 09:42 09:49 09:53 10:23 10:49 11:07 11:16 11:35 here are hundreds of thousands of people lining On the opposite page is a specially formulated pace guide to 9 09:47 09:53 09:57 10:28 10:57 11:17 11:28 11:48 the route of the Flora London Marathon every year, help you follow the top flight action in the elite races. -

Liverpool Street Bus Station Closure

Liverpool Street bus station closed - changes to routes 11, 23, 133, N11 and N133 The construction of the new Crossrail ticket hall in Liverpool Street is progressing well. In order to build a link between the new ticket hall and the Underground station, it will be necessary to extend the Crossrail hoardings across Old Broad Street. This will require the temporary closure of the bus station from Sunday 22 November until Spring 2016. Routes 11, 23 and N11 Buses will start from London Wall (stop ○U) outside All Hallows Church. Please walk down Old Broad Street and turn right at the traffic lights. The last stop for buses towards Liverpool Street will be in Eldon Street (stop ○V). From there it is 50 metres to the steps that lead down into the main National Rail concourse where you can also find the entrance to the Underground station. Buses in this direction will also be diverted via Princes Street and Moorgate, and will not serve Threadneedle Street or Old Broad Street. Routes 133 and N133 The nearest stop will be in Wormwood Street (stop ○Q). Please walk down Old Broad Street and turn left along Wormwood Street after using the crossing to get to the opposite side of the road. The last stop towards Liverpool Street will also be in Wormwood Street (stop ○P). Changes to routes 11, 23, 133, N11 & N133 Routes 11, 23, 133, N11 & N133 towards Liverpool Street Routes 11 & N11 towards Bank, Aldwych, Victoria and Fulham Route 23 towards Bank, Aldwych, Oxford Circus and Westbourne Park T E Routes 133 & N133 towards London Bridge, Elephant & Castle, -

Some Named Brewhouses in Early London Mike Brown

Some named brewhouses in early London Mike Brown On the river side, below St. Katherine's, says ed to be somewhat dispersed through a Pennant, on we hardly know what authority, variety of history texts. Members will be stood, in the reign of the Tudors, the great aware that the Brewery History Society breweries of London, or the "bere house," as has gradually been covering the history it is called in the map of the first volume of of brewing in individual counties, with a the "Civitates Orbis." They were subject to series of books. Some of these, such as the usual useful, yet vexatious, surveillance Ian Peaty's Essex and Peter Moynihan's of the olden times; and in 1492 (Henry VII.) work on Kent, have included parts of the king licensed John Merchant, a Fleming, London in the wider sense ie within the to export fifty tuns of ale "called berre;" and in M25. There are also histories of the main the same thrifty reign one Geffrey Gate concerns eg Red Barrel on Watneys, but (probably an officer of the king's) spoiled the they often see the business from one par- brew-houses twice, either by sending abroad ticular perspective. too much beer unlicensed, or by brewing it too weak for the sturdy home customers. The Hence, to celebrate the Society’s 40th demand for our stalwart English ale anniversary and to tie in with some of the increased in the time of Elizabeth, in whose events happening in London, it was felt reign we find 500 tuns being exported at one that it was time to address the question time alone, and sent over to Amsterdam of brewing in the capital - provisionally probably, as Pennant thinks, for the use of entitled Capital Ale or similar - in a single our thirsty army in the Low Countries.