MARS Detection and Characterization of Rocks and Rock Size-Frequency Distributions at the Final Four Mars Science Laboratory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selection of the Insight Landing Site M. Golombek1, D. Kipp1, N

Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript InSight Landing Site Paper v9 Rev.docx Click here to view linked References Selection of the InSight Landing Site M. Golombek1, D. Kipp1, N. Warner1,2, I. J. Daubar1, R. Fergason3, R. Kirk3, R. Beyer4, A. Huertas1, S. Piqueux1, N. E. Putzig5, B. A. Campbell6, G. A. Morgan6, C. Charalambous7, W. T. Pike7, K. Gwinner8, F. Calef1, D. Kass1, M. Mischna1, J. Ashley1, C. Bloom1,9, N. Wigton1,10, T. Hare3, C. Schwartz1, H. Gengl1, L. Redmond1,11, M. Trautman1,12, J. Sweeney2, C. Grima11, I. B. Smith5, E. Sklyanskiy1, M. Lisano1, J. Benardino1, S. Smrekar1, P. Lognonné13, W. B. Banerdt1 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109 2State University of New York at Geneseo, Department of Geological Sciences, 1 College Circle, Geneseo, NY 14454 3Astrogeology Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, 2255 N. Gemini Dr., Flagstaff, AZ 86001 4Sagan Center at the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035 5Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302; Now at Planetary Science Institute, Lakewood, CO 80401 6Smithsonian Institution, NASM CEPS, 6th at Independence SW, Washington, DC, 20560 7Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Imperial College, South Kensington Campus, London 8German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Planetary Research, 12489 Berlin, Germany 9Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA; Now at Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA 98926 10Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996 11Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712 12MS GIS Program, University of Redlands, 1200 E. Colton Ave., Redlands, CA 92373-0999 13Institut Physique du Globe de Paris, Paris Cité, Université Paris Sorbonne, France Diderot Submitted to Space Science Reviews, Special InSight Issue v. -

Owner's Manual,1996 Pontiac Bonneville

I LLt -The 1996 Pontiac Bonneville Owner’s Manual Seats and Restraint Systems ............................................................. 1-1 This section tells you how to use your seats and safety belts properly. It also explains“SRS” the system. Features and Controls ..................... ;............................................ 2-1 This section explainshow to start and operate your Pontiac. Comfort Controls and Audio Systems ...................................................... 3-1 This section tells you how to adjust the ventilation and comfort controls andhow to operate your audio system. Your Driving and the Road .............................................................. 4-1 Here you’ll find helpful information and tips about the roadhow and to drive under different conditions. ProblemsontheRoad .................................................................. 5-1 This section tells you whatto do if you have a problem whiledriving, such as a flat tire or overheated engine, etc. Service and Appearance Care.. .......................................................... 6-1 Here the manual tellsyou how to keep your Pontiacrunning properly and looking good. Maintenanceschedule......... .......................................................... 7-1 This section tellp you when to perform vehicle maintenance and what fluidsand lubricants to use. Customer Assistance Information ... .#.................................................... 8-1 \ This section tells youhow to contact Pontiac for assistance and how to get service and -

Mars Exploration: an Overview of Indian and International Mars Missions Nayamavalsa Scariah1, Dr

Taurian Innovative Journal/Volume 1/ Issue 1 Mars exploration: An overview of Indian and International Mars Missions NayamaValsa Scariah1, Dr. Mili Ghosh2, Dr.A.P.Krishna3 Birla Institute of Technology, Mesra, Ranchi Abstract- Mars is the fourth planet from the sun. It is 1. Introduction also known as red planet because of its iron oxide content. There are lots of missions have been launched to Mars is also known as red planet, because of the mars for better understanding of our neighboring planet. reddish iron oxide prevalent on its surface gives it a There are lots of unmanned spacecraft including reddish appearance. It is the fourth planet from sun. orbiters, landers and rovers have been launched into mars since early 1960. Sputnik was the first satellite The term sol is used to define duration of solar day on launched in 1957 by Soviet Union. After seven failure Mars. A mean Martian solar day or sol is 24 hours 39 missions to Mars, Mariner 4 was the first satellite which minutes and 34.244 seconds. Many space missions to reached the Martian orbiter successfully. The Viking 1 Mars have been planned and launched for Mars was the first lander reached on Mars on 1975. India exploration (Table:1) but most of them failed without successfully launched a spacecraft, Mangalyan (Mars completing the task specially in early attempts th Orbiter Mission) on 5 November, 2013, with five whereas some NASA missions were very payloads to Mars. India was the first nation to successful(such as the twin Mars Exploration Rovers, successfully reach Mars on its first attempt. -

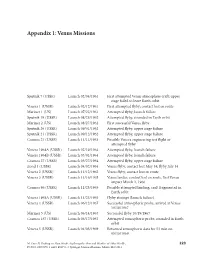

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

Widespread Excess Ice in Arcadia Planitia, Mars

Widespread Excess Ice in Arcadia Planitia, Mars Ali M. Bramson1, Shane Byrne1, Nathaniel E. Putzig2, Sarah Sutton1, Jeffrey J. Plaut3, T. Charles Brothers4 and John W. Holt4 Corresponding author: A. M. Bramson, Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Kuiper Space Science Building, 1629 E. University Blvd. Tucson, AZ, 85721, USA. ([email protected]) Affiliations: 1Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA. 2Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado, USA. 3Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, USA. 4Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, USA. Accepted for publication July 18, 2015 in Geophysical Research Letters. An edited version of this paper was published by AGU on August 26, 2015. Copyright 2015 American Geophysical Union. Citation: Bramson, A. M., S. Byrne, N. E. Putzig, S. Sutton, J. J. Plaut, T. C. Brothers, and J. W. Holt (2015), Widespread excess ice in Arcadia Planitia, Mars, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, doi:10.1002/2015GL064844. Key points: • Terraced craters: abundant in Arcadia Planitia, indicate subsurface layering • A widespread subsurface interface is also detected by SHARAD • Combining data sets yields dielectric constants consistent with decameters of excess water ice Abstract: The distribution of subsurface water ice on Mars is a key constraint on past climate, while the volumetric concentration of buried ice (pore-filling versus excess) provides information about the process that led to its deposition. We investigate the subsurface of Arcadia Planitia by measuring the depth of terraces in simple impact craters and mapping a widespread subsurface reflection in radar sounding data. Assuming that the contrast in material strengths responsible for the terracing is the same dielectric interface that causes the radar reflection, we can combine these data to estimate the dielectric constant of the overlying material. -

Geologic Map of the Twin Falls 30 X 60 Minute Quadrangle, Idaho

Geologic Map of the Twin Falls 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangle, Idaho Compiled and Mapped by Kurt L. Othberg, John D. Kauffman, Virginia S. Gillerman, and Dean L. Garwood 2012 Idaho Geological Survey Third Floor, Morrill Hall University of Idaho Geologic Map 49 Moscow, Idaho 83843-3014 2012 Geologic Map of the Twin Falls 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangle, Idaho Compiled and Mapped by Kurt L. Othberg, John D. Kauffman, Virginia S. Gillerman, and Dean L. Garwood INTRODUCTION 43˚ 115˚ The geology in the 1:100,000-scale Twin Falls 30 x 23 13 18 7 8 25 60 minute quadrangle is based on field work conduct- ed by the authors from 2002 through 2005, previous 24 17 14 16 19 20 26 1:24,000-scale maps published by the Idaho Geological Survey, mapping by other researchers, and compilation 11 10 from previous work. Mapping sources are identified 9 15 12 6 in Figures 1 and 2. The geologic mapping was funded in part by the STATEMAP and EDMAP components 5 1 2 22 21 of the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Cooperative 4 3 42˚ 30' Geologic Mapping Program (Figure 1). We recognize 114˚ that small map units in the Snake River Canyon are dif- 1. Bonnichsen and Godchaux, 1995a 15. Kauffman and Othberg, 2005a ficult to identify at this map scale and we direct readers 2. Bonnichsen and Godchaux, 16. Kauffman and Othberg, 2005b to the 1:24,000-scale geologic maps shown in Figure 1. 1995b; Othberg and others, 2005 17. Kauffman and others, 2005a 3. -

Carbon Monoxide As a Metabolic Energy Source for Extremely Halophilic Microbes: Implications for Microbial Activity in Mars Regolith

Carbon monoxide as a metabolic energy source for extremely halophilic microbes: Implications for microbial activity in Mars regolith Gary M. King1 Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803 Edited by David M. Karl, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, and approved March 5, 2015 (received for review December 31, 2014) Carbon monoxide occurs at relatively high concentrations (≥800 that low organic matter levels might indeed occur in some deposits parts per million) in Mars’ atmosphere, where it represents a poten- (e.g., 12). Even so, it is uncertain whether this material exists in a tially significant energy source that could fuel metabolism by a local- form or concentrations suitable for microbial use. ized putative surface or near-surface microbiota. However, the The Martian atmosphere has largely been ignored as a potential plausibility of CO oxidation under conditions relevant for Mars in energy source, because it is dominated by CO2 (24, 25). Ironically, its past or at present has not been evaluated. Results from diverse UV photolysis of CO2 forms carbon monoxide (CO), a potential terrestrial brines and saline soils provide the first documentation, to bacterial substrate that occurs at relatively high concentrations: our knowledge, of active CO uptake at water potentials (−41 MPa to about 800 ppm on average, with significantly higher levels for −117 MPa) that might occur in putative brines at recurrent slope some sites and times (26, 27). In addition, molecular oxygen lineae (RSL) on Mars. Results from two extremely halophilic iso- (O2), which can serve as a biological CO oxidant, occurs at lates complement the field observations. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Getting to Mars How Close Is Mars?

Getting to Mars How close is Mars? Exploring Mars 1960-2004 Of 42 probes launched: 9 crashed on launch or failed to leave Earth orbit 4 failed en route to Mars 4 failed to stop at Mars 1 failed on entering Mars orbit 1 orbiter crashed on Mars 6 landers crashed on Mars 3 flyby missions succeeded 9 orbiters succeeded 4 landers succeeded 1 lander en route Score so far: Earthlings 16, Martians 25, 1 in play Mars Express Mars Exploration Rover Mars Exploration Rover Mars Exploration Rover 1: Meridiani (Opportunity) 2: Gusev (Spirit) 3: Isidis (Beagle-2) 4: Mars Polar Lander Launch Window 21: Jun-Jul 2003 Mars Express 2003 Jun 2 In Mars orbit Dec 25 Beagle 2 Lander 2003 Jun 2 Crashed at Isidis Dec 25 Spirit/ Rover A 2003 Jun 10 Landed at Gusev Jan 4 Opportunity/ Rover B 2003 Jul 8 Heading to Meridiani on Sunday Launch Window 1: Oct 1960 1M No. 1 1960 Oct 10 Rocket crashed in Siberia 1M No. 2 1960 Oct 14 Rocket crashed in Kazakhstan Launch Window 2: October-November 1962 2MV-4 No. 1 1962 Oct 24 Rocket blew up in parking orbit during Cuban Missile Crisis 2MV-4 No. 2 "Mars-1" 1962 Nov 1 Lost attitude control - Missed Mars by 200000 km 2MV-3 No. 1 1962 Nov 4 Rocket failed to restart in parking orbit The Mars-1 probe Launch Window 3: November 1964 Mariner 3 1964 Nov 5 Failed after launch, nose cone failed to separate Mariner 4 1964 Nov 28 SUCCESS, flyby in Jul 1965 3MV-4 No. -

FIELD STUDIES of CRATER GRADATION in GUSEV CRATER and MERIDIANI PLANUM USING the MARS EXPLORATION ROVERS. J. A. Grant1, M. P. Golombek2, A

Role of Volatiles and Atmospheres on Martian Impact Craters 2005 3004.pdf FIELD STUDIES OF CRATER GRADATION IN GUSEV CRATER AND MERIDIANI PLANUM USING THE MARS EXPLORATION ROVERS. J. A. Grant1, M. P. Golombek2, A. F. C. Haldemann2, L. Crumpler3, R. Li4, W. A. Watters5, and the Athena Science Team 1Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560, 2Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Tech- nology, Pasadena, CA 91109, 3New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Albuquerque, NM 87104, 4Department of Civil Engineering and Remote Sensing, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, 5Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139. Introduction: The Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit Impact Structures in Meridiani Planum: Craters and Opportunity investigated numerous craters since explored at Meridiani are fewer and farther between landing in Gusev crater (14.569oS, 175.473oE) and than at Gusev and all are formed into sulfate bedrock Meridiani Planum (1.946oS, 354.473oE) over the first [3]. With the exception of the most degraded examples, 400 sols of their missions [1-4]. Craters at both sites Meridiani craters have depth-to-diameter ratios >0.10 are simple structures and vary in size and preservation and preserve walls sloped generally >10 degrees. En- state. Comparing observed and expected pristine mor- durance crater is 150 m-in-diameter, 22 m deep, and phology and using process-specific gradational signa- possesses walls sloped between 15-30 degrees, but tures around terrestrial craters as a template [5-7] al- locally exceeding the repose angle (Table 1). -

Mars Insight Launch Press Kit

Introduction National Aeronautics and Space Administration Mars InSight Launch Press Kit MAY 2018 www.nasa.gov 1 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction 4 Media Services 8 Quick Facts: Launch Facts 12 Quick Facts: Mars at a Glance 16 Mission: Overview 18 Mission: Spacecraft 30 Mission: Science 40 Mission: Landing Site 53 Program & Project Management 55 Appendix: Mars Cube One Tech Demo 56 Appendix: Gallery 60 Appendix: Science Objectives, Quantified 62 Appendix: Historical Mars Missions 63 Appendix: NASA’s Discovery Program 65 3 Introduction Mars InSight Launch Press Kit Introduction NASA’s next mission to Mars -- InSight -- will launch from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California as early as May 5, 2018. It is expected to land on the Red Planet on Nov. 26, 2018. InSight is a mission to Mars, but it is more than a Mars mission. It will help scientists understand the formation and early evolution of all rocky planets, including Earth. A technology demonstration called Mars Cube One (MarCO) will share the launch with InSight and fly separately to Mars. Six Ways InSight Is Different NASA has a long and successful track record at Mars. Since 1965, it has flown by, orbited, landed and roved across the surface of the Red Planet. None of that has been easy. Only about 40 percent of the missions ever sent to Mars by any space agency have been successful. The planet’s thin atmosphere makes landing a challenge; its extreme temperature swings make it difficult to operate on the surface. But if a spacecraft survives the trip, there’s a bounty of science to be collected.