Feasibility Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release Address: Email and Homepage: U.S

News Release Address: Email and Homepage: U.S. Department of the Interior Maryland-Delaware-D.C. District [email protected] U.S. Geological Survey 8987 Yellow Brick Road http://md.water.usgs.gov/ Baltimore, MD 21237 Release: Contact: Phone: Fax: January 4, 2002 Wendy S. McPherson (410) 238-4255 (410) 238-4210 Below Normal Rainfall and Warm Temperatures Lead to Record Low Water Levels in December Three months of above normal temperatures and four months of below normal rainfall have led to record low monthly streamflow and ground-water levels, according to hydrologists at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Baltimore, Maryland. Streamflow was below normal at 94 percent of the real-time USGS gaging stations and 83 percent of the USGS observation wells across Maryland and Delaware in December. Record low streamflow levels for December were set at Winters Run and Pocomoke River. Streamflow levels at Deer Creek and Winters Run in Harford County have frequently set new record daily lows for the last four months (see real-time graphs at http://md.water.usgs.gov/realtime/). Streamflow was also significantly below normal at Antietam Creek, Choptank River, Conococheague Creek, Nassawango Creek, Patapsco River, Gunpowder River, Patuxent River, Piscataway Creek, Monocacy River, and Potomac River in Maryland, and Christina River, St. Jones River, and White Clay Creek in Delaware. The monthly streamflow in the Potomac River near Washington, D.C. was 82 percent below normal in December and 54 percent below normal for 2001. Streamflow entering the Chesapeake Bay averaged 23.7 bgd (billion gallons per day), which is 54 percent below the long-term average for December. -

Flood Insurance Study

FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY CECIL COUNTY, MARYLAND AND INCORPORATED AREAS Cecil County Community Community Name Number ↓ CECIL COUNTY (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) 240019 *CECILTON, TOWN OF 240020 CHARLESTOWN, TOWN OF 240021 CHESAPEAKE CITY, TOWN OF 240099 ELKTON, TOWN OF 240022 NORTH EAST, TOWN OF 240023 PERRYVILLE, TOWN OF 240024 PORT DEPOSIT, TOWN OF 240025 RISING SUN, TOWN OF 240158 *No Special Flood Hazard Areas Identified Revised: May 4, 2015 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 24015CV000B NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. Part or all of this FIS may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of the FIS may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision (LOMR) process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current FIS components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: July 8, 2013 Revised Countywide FIS Effective Date: May 4, 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. -

Simulation of Streamflow and Water Quality in the Brandywine Creek Subbasin of the Christina River Basin, Pennsylvania and Delaware, 1994-98

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey SIMULATION OF STREAMFLOW AND WATER QUALITY IN THE BRANDYWINE CREEK SUBBASIN OF THE CHRISTINA RIVER BASIN, PENNSYLVANIA AND DELAWARE, 1994-98 Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4279 In cooperation with the DELAWARE RIVER BASIN COMMISSION, DELAWARE DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL, and the PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey SIMULATION OF STREAMFLOW AND WATER QUALITY IN THE BRANDYWINE CREEK SUBBASIN OF THE CHRISTINA RIVER BASIN, PENNSYLVANIA AND DELAWARE, 1994-98 by Lisa A. Senior and Edward H. Koerkle Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4279 In cooperation with the DELAWARE RIVER BASIN COMMISSION, DELAWARE DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL, and the PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION New Cumberland, Pennsylvania 2003 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For additional information Copies of this report may be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 215 Limekiln Road Box 25286, Federal Center New Cumberland, Pennsylvania 17070-2424 Denver, Colorado 80225-0286 Email: [email protected] Telephone 1-888-ASK-USGS Internet address: http://pa.water.usgs.gov ii CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 2 Purpose and scope . 4 Previous studies . 5 Acknowledgments . 5 Description of study area . 5 Physical setting . 5 Climate . 5 Geology . 6 Soils. 6 Hydrology . 6 Land use. 8 Water use . 8 Description of model . 8 Data for model input and calibration . 10 Model-input data . -

Background Research

BACKGROUND RESEARCH PREVIOUS INVESTIGATIONS Several archaeological investigations have been completed in the project vicinity, most of them associated with the building of SR 1 (Table 1). Figures 3-7 show the locations of these studies and the known archaeological sites in the APE. Table 1: Previous Archaeological Studies in the APE DESCRIPTION REFERENCE Phase I Archaeological Survey, Routes 4, 7, 273 Thomas 1980 Archaeological Planning Survey of the SR 1 Corridor Custer and Bachman 1986 Phase I and II Archaeological Studies, Route 7 South Corridor Catts et al. 1988 Archaeological Testing and Historical Investigations of “The Place at Catts et a. 1989 Christeen” Phase I Archaeological Survey of the SR 1 Canal Section, Red Lion Hodny et al. 1989 Creek to Scott Run Phase II Archaeological Testing of the Lewden Green Site, 7NC-E-9 Custer et al. 1990 Phase I Survey of Waterline Near Route 13/72 Intersection Mellin and Baumgardt 1990 Management plan for Delaware’s historic archaeological resources De Cunzo and Catts 1990 Cultural Resource Planning Study for the proposed Route 301 Corridor, Kellogg 1992 New Castle County Phase II Archaeological Investigations, SR 1 Canal Section Kellogg et al. 1994 Paleoenvironmental Studies of the SR 1 Corridor Kellogg and Custer 1994 Phase III Archaeological Excavations of the Wrangle Hill Site (7NC-G- Custer et al. 1995 105) Phase III Archaeological Excavations of the Snapp Site (7NC-G-101) Custer and Silber 1995 Phase I and II Testing at Scott Run and the Route 13/72 Interchange, and Doms et al. 1995 Phase III Mitigation of the Woodville Grave Site Phase I and II Archaeological Investigations in the SR 1 Corridor, Scott Bedell et al. -

Maryland Stream Waders 10 Year Report

MARYLAND STREAM WADERS TEN YEAR (2000-2009) REPORT October 2012 Maryland Stream Waders Ten Year (2000-2009) Report Prepared for: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 1-877-620-8DNR (x8623) [email protected] Prepared by: Daniel Boward1 Sara Weglein1 Erik W. Leppo2 1 Maryland Department of Natural Resources Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division 580 Taylor Avenue; C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 2 Tetra Tech, Inc. Center for Ecological Studies 400 Red Brook Boulevard, Suite 200 Owings Mills, Maryland 21117 October 2012 This page intentionally blank. Foreword This document reports on the firstt en years (2000-2009) of sampling and results for the Maryland Stream Waders (MSW) statewide volunteer stream monitoring program managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) Monitoring and Non-tidal Assessment Division (MANTA). Stream Waders data are intended to supplementt hose collected for the Maryland Biological Stream Survey (MBSS) by DNR and University of Maryland biologists. This report provides an overview oft he Program and summarizes results from the firstt en years of sampling. Acknowledgments We wish to acknowledge, first and foremost, the dedicated volunteers who collected data for this report (Appendix A): Thanks also to the following individuals for helping to make the Program a success. • The DNR Benthic Macroinvertebrate Lab staffof Neal Dziepak, Ellen Friedman, and Kerry Tebbs, for their countless hours in -

Coast Guard, DHS § 162.65

Coast Guard, DHS § 162.65 (2) No vessels having a height of more with moorings and lines which are suf- than 35 feet with reference to the plane ficient and proper. of mean high water shall enter or pass (c) Right-of-way. All vessels pro- through the area whenever visibility is ceeding with the current shall have the less than one mile. right-of-way over those proceeding against the current. Large vessels or § 162.30 Channel of Tuckerton Creek, tows must not overtake and attempt to N.J.; navigation. pass other large vessels or tows in the (a) Power boats or other vessels pro- waterway. All small pleasure craft pelled by machinery shall not proceed shall relinquish the right-of-way to deeper draft vessels, which have a lim- at any time within the limits of these ited maneuvering ability due to their waters at a greater speed than 8 stat- draft and size. ute miles per hour. (d) Stopping in waterway. Vessels will not be permitted to stop or anchor in § 162.35 Channel of Christina River, Del.; navigation. the ship channel. (e) Water skiing. Water skiing in the (a) That vessels of over 20 tons capac- waterway is prohibited between Reedy ity, propelled by machinery, shall not Point and Welch Point. proceed at any time within the limits (f) Sailboats. Transiting the canal by of these waters at a greater speed than vessels under sail is not permitted be- 8 statute miles per hour. tween Reedy Point and Welch Point. NOTE: The Corps of Engineers also has reg- § 162.40 Inland waterway from Dela- ulations dealing with this section in 33 CFR ware River to Chesapeake Bay, Del. -

Underground Railroad Byway Delaware

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway Delaware Chapter 3.0 Intrinsic Resource Assessment The following Intrinsic Resource Assessment chapter outlines the intrinsic resources found along the corridor. The National Scenic Byway Program defines an intrinsic resource as the cultural, historical, archeological, recreational, natural or scenic qualities or values along a roadway that are necessary for designation as a Scenic Byway. Intrinsic resources are features considered significant, exceptional and distinctive by a community and are recognized and expressed by that community in its comprehensive plan to be of local, regional, statewide or national significance and worthy of preservation and management (60 FR 26759). Nationally significant resources are those that tend to draw travelers or visitors from regions throughout the United States. National Scenic Byway CMP Point #2 An assessment of the intrinsic qualities and their context (the areas surrounding the intrinsic resources). The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway offers travelers a significant amount of Historical and Cultural resources; therefore, this CMP is focused mainly on these resource categories. The additional resource categories are not ignored in this CMP; they are however, not at the same level of significance or concentration along the corridor as the Historical and Cultural resources. The resources represented in the following chapter provide direct relationships to the corridor story and are therefore presented in this chapter. A map of the entire corridor with all of the intrinsic resources displayed can be found on Figure 6. Figures 7 through 10 provide detailed maps of the four (4) corridors segments, with the intrinsic resources highlighted. This Intrinsic Resource Assessment is organized in a manner that presents the Primary (or most significant resources) first, followed by the Secondary resources. -

Selected Streamflow Statistics for Streamgage Locations in and Near Pennsylvania

Prepared in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Selected Streamflow Statistics for Streamgage Locations in and near Pennsylvania Open-File Report 2011–1070 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Tunkhannock Creek and Highway 6 overpass downstream from U.S. Geological Survey streamgage 01534000 Tunkhannock Creek near Tunkhannock, PA. (Photo by Andrew Reif, USGS) Selected Streamflow Statistics for Streamgage Locations in and near Pennsylvania By Marla H. Stuckey and Mark A. Roland Prepared in cooperation with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection Open-File Report 2011–1070 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2011 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Stuckey, M.H., and Roland, M.A., 2011, Selected streamflow statistics for streamgage locations in and near Pennsyl- vania: U.S. -

Christina River Wetland Condition Report

Matthew A. Jennette Alison B. Rogerson Andrew M. Howard Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control Division of Watershed Stewardship 820 Silver Lake Blvd, Suite 220 Dover, DE 19904 LeeAnn Haaf Danielle Kreeger Angela Padeletti Kurt Cheng Jessie Buckner Partnership for the Delaware Estuary 110 South Poplar Street, Suite 202 Wilmington, DE 19801 The citation for this document is: Jennette, M.A., L. Haaf, A.B. Rogerson, A.M. Howard, D. Kreeger, A. Padeletti, K. Cheng, and J. Buckner. 2014. Condition of Wetlands in the Christiana River Watershed. Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, Watershed Assessment and Management Section, Dover, DE and the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary, Wilmington, DE. ii Christina River Wetland Condition ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this project was provided by EPA Region III Wetland Program Development Grant Assistance # CD-96312201-0, EPA National Estuary Program, the Delaware Department of Natural Resources, and the DuPont Clear into the Future program. Technical support and field research was made possible by the contributions of many individuals. Tracy Quirk and Melanie Mills from the Academy of Natural Science of Drexel University (ANS) for the collection and analysis of Site Specific data, and assistance with RAM data collection and analysis. Tom Kincaid and Tony Olsen with the EPA Office of Research and Development Lab, Corvallis, Oregon provided the data frame for field sampling and statistical weights for interpretation. Kristen Kyler and Rebecca Rothweiler participated in many field assessments under a myriad of conditions. Maggie Pletta and Michelle Lepori-Bui were helpful with revisions on drafts of the report, as well as producing the cover art for the final document. -

A Summary of Peak Stages Discharges in Maryland, Delaware

I : ' '; Ji" ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY · Water Resources Division A SUMMARY OF PEAK STAGES AND DISCHARGES IN MARYLAND, DELAWARE, AND DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FOR FLOOD OF JUNE 1972 by Kenneth R. Taylor Open-File Report Parkville, Maryland 1972 A SUJ1D11ary of Peak Stages and Discharges in Maryland, Delaware, and District of Columbia for Flood of June 1972 by Kenneth R. Taylor • Intense rainfall associated with tropical storm Agnes caused devastating flooding in several states along the Atlantic Seaboard during late June 1972. Storm-related deaths were widespread from Florida to New York, and public and private property damage has been estllna.ted in the billions of dollars. The purpose of this report is to make available to the public as quickly as possible peak-stage and peak-discharge data for streams and rivers in Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia. Detailed analyses of precipitation, flood damages, stage hydrographs, discharge hydrographs, and frequency relations will be presented in a subsequent report. Although the center of the storm passed just offshore from Maryland and Delaware, the most intense rainfall occurred in the Washington, D. c., area and in a band across the central part of Maryland (figure 1). Precipitation totals exceeding 10 inches during the June 21-23 period • were recorded in Baltimore, Carroll, Cecil, Frederick, Harford, Howard, Kent, Montgomery, and Prince Georges Counties, Md., and in the District of Columbia. Storm totals of more than 14 inches were recorded in Baltimore and Carroll Counties. At most stations more than 75 percent of the storm rainfall'occurred on the afternoon and night of June 21 and the morning of June 22 (figure 2). -

Watersheds.Pdf

Watershed Code Watershed Name 02130705 Aberdeen Proving Ground 02140205 Anacostia River 02140502 Antietam Creek 02130102 Assawoman Bay 02130703 Atkisson Reservoir 02130101 Atlantic Ocean 02130604 Back Creek 02130901 Back River 02130903 Baltimore Harbor 02130207 Big Annemessex River 02130606 Big Elk Creek 02130803 Bird River 02130902 Bodkin Creek 02130602 Bohemia River 02140104 Breton Bay 02131108 Brighton Dam 02120205 Broad Creek 02130701 Bush River 02130704 Bynum Run 02140207 Cabin John Creek 05020204 Casselman River 02140305 Catoctin Creek 02130106 Chincoteague Bay 02130607 Christina River 02050301 Conewago Creek 02140504 Conococheague Creek 02120204 Conowingo Dam Susq R 02130507 Corsica River 05020203 Deep Creek Lake 02120202 Deer Creek 02130204 Dividing Creek 02140304 Double Pipe Creek 02130501 Eastern Bay 02141002 Evitts Creek 02140511 Fifteen Mile Creek 02130307 Fishing Bay 02130609 Furnace Bay 02141004 Georges Creek 02140107 Gilbert Swamp 02130801 Gunpowder River 02130905 Gwynns Falls 02130401 Honga River 02130103 Isle of Wight Bay 02130904 Jones Falls 02130511 Kent Island Bay 02130504 Kent Narrows 02120201 L Susquehanna River 02130506 Langford Creek 02130907 Liberty Reservoir 02140506 Licking Creek 02130402 Little Choptank 02140505 Little Conococheague 02130605 Little Elk Creek 02130804 Little Gunpowder Falls 02131105 Little Patuxent River 02140509 Little Tonoloway Creek 05020202 Little Youghiogheny R 02130805 Loch Raven Reservoir 02139998 Lower Chesapeake Bay 02130505 Lower Chester River 02130403 Lower Choptank 02130601 Lower -

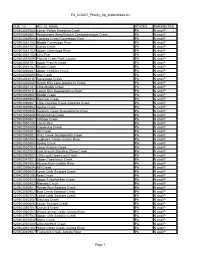

PA COAST Priority Ag Watersheds.Xls

PA_COAST_Priority_Ag_Watersheds.xls HUC_12 HU_12_NAME STATES PARAMETER 020503050505 Lower Yellow Breeches Creek PA N and P 020700040601 Headwaters West Branch Conococheague Creek PA N and P 020503060904 Cocalico Creek-Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061104 Middle Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061701 Conoy Creek PA N and P 020503061103 Upper Conestoga River PA N and P 020503061105 Lititz Run PA N and P 020503051009 Fishing Creek-York County PA N and P 020402030701 Upper French Creek PA N and P 020503061102 Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503060801 Upper Chickies Creek PA N and P 020402030608 Hay Creek PA N and P 020503051010 Conewago Creek PA N and P 020402030606 Green Hills Lake-Allegheny Creek PA N and P 020503061101 Little Muddy Creek PA N and P 020503051011 Laurel Run-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020503060902 Middle Creek PA N and P 020503060903 Hammer Creek PA N and P 020503060901 Little Cocalico Creek-Cocalico Creek PA N and P 020503050904 Spring Creek PA N and P 020503050906 Swatara Creek-Susquehanna River PA N and P 020402030605 Wyomissing Creek PA N and P 020503050801 Killinger Creek PA N and P 020503050105 Laurel Run PA N and P 020402030408 Cacoosing Creek PA N and P 020402030401 Mill Creek PA N and P 020503050802 Snitz Creek-Quittapahilla Creek PA N and P 020503040404 Aughwick Creek-Juniata River PA N and P 020402030406 Spring Creek PA N and P 020402030702 Lower French Creek PA N and P 020503020703 East Branch Standing Stone Creek PA N and P 020503040802 Little Lost Creek-Lost Creek PA N and P 020503041001 Upper Cocolamus Creek