Graph Drawing and Cartography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover Materials Infographic Challenge

Website: www.discovermaterials.uk Twitter: @DiscovMaterials Instagram: @discovermaterials Email: [email protected] Discover Materials Infographic Challenge The Challenge: We would like you to produce an infographic that highlights and explores a material that has been important to you during the pandemic. We will be awarding prizes for the top two infographics based upon the following criteria: visual appeal content (facts/depth/breadth) range of sources Entries must be submitted to: [email protected] by 9pm (BST) on Sunday 2nd August and submitted as a picture file. Please include your name, as the author of the infographic, within the image. In submitting the infographic to be judged, you are agreeing that the graphic can be shared by Discover Materials more widely. Introduction: An infographic provides us with a short, interesting and timely manner to communicate a complex idea with the wider public. An important aspect of using an infographic is that our target is to make something with high shareability and this can be achieved by telling a good story with a design that conveys data in a manner that is easily interpreted, as highlighted in Figure 1. In this challenge we want you to consider a material that has been important in the pandemic. There are a huge range of materials that have been vitally important to us all during these chaotic and challenging times. We could imagine materials that have been important in personal protection & healthcare, materials that Figure 1: The overlapping aspects of a good infographic enable our new forms of engagement and https://www.flickr.com/photos/dashburst/8448339735 communication in the digital world, or the ‘day- to-day’ materials that we rely upon and without which we would find modern life incredibly difficult. -

Visual Literacy of Infographic Review in Dkv Students’ Works in Bina Nusantara University

VISUAL LITERACY OF INFOGRAPHIC REVIEW IN DKV STUDENTS’ WORKS IN BINA NUSANTARA UNIVERSITY Suprayitno School of Design New Media Department, Bina Nusantara University Jl. K. H. Syahdan, No. 9, Palmerah, Jakarta 11480, Indonesia [email protected] ABSTRACT This research aimed to provide theoretical benefits for students, practitioners of infographics as the enrichment, especially for Desain Komunikasi Visual (DKV - Visual Communication Design) courses and solve the occurring visual problems. Theories related to infographic problems were used to analyze the examples of the student's infographic work. Moreover, the qualitative method was used for data collection in the form of literature study, observation, and documentation. The results of this research show that in general the students are less precise in the selection and usage of visual literacy elements, and the hierarchy is not good. Thus, it reduces the clarity and effectiveness of the infographic function. This is the urgency of this study about how to formulate a pattern or formula in making a work that is not only good and beautiful but also is smart, creative, and informative. Keywords: visual literacy, infographic elements, Visual Communication Design, DKV INTRODUCTION Desain Komunikasi Visual (DKV - Visual Communication Design) is a term portrayal of the process of media in communicating an idea or delivery of information that can be read or seen. DKV is related to the use of signs, images, symbols, typography, illustrations, and color. Those are all related to the sense of sight. In here, the process of communication can be through the exploration of ideas with the addition of images in the form of photos, diagrams, illustrations, and colors. -

Maps and Diagrams. Their Compilation and Construction

~r HJ.Mo Mouse andHR Wilkinson MAPS AND DIAGRAMS 8 his third edition does not form a ramatic departure from the treatment of artographic methods which has made it a standard text for 1 years, but it has developed those aspects of the subject (computer-graphics, quantification gen- erally) which are likely to progress in the uture. While earlier editions were primarily concerned with university cartography ‘ourses and with the production of the- matic maps to illustrate theses, articles and books, this new edition takes into account the increasing number of professional cartographer-geographers employed in Government departments, planning de- partments and in the offices of architects pnd civil engineers. The authors seek to ive students some idea of the novel and xciting developments in tools, materials, echniques and methods. The growth, mounting to an explosion, in data of all inds emphasises the increasing need for discerning use of statistical techniques, nevitably, the dependence on the com- uter for ordering and sifting data must row, as must the degree of sophistication n the techniques employed. New maps nd diagrams have been supplied where ecessary. HIRD EDITION PRICE NET £3-50 :70s IN U K 0 N LY MAPS AND DIAGRAMS THEIR COMPILATION AND CONSTRUCTION MAPS AND DIAGRAMS THEIR COMPILATION AND CONSTRUCTION F. J. MONKHOUSE Formerly Professor of Geography in the University of Southampton and H. R. WILKINSON Professor of Geography in the University of Hull METHUEN & CO LTD II NEW FETTER LANE LONDON EC4 ; © ig6g and igyi F.J. Monkhouse and H. R. Wilkinson First published goth October igj2 Reprinted 4 times Second edition, revised and enlarged, ig6g Reprinted 3 times Third edition, revised and enlarged, igyi SBN 416 07440 5 Second edition first published as a University Paperback, ig6g Reprinted 5 times Third edition, igyi SBN 416 07450 2 Printed in Great Britain by Richard Clay ( The Chaucer Press), Ltd Bungay, Suffolk This title is available in both hard and paperback editions. -

Graph Visualization and Navigation in Information Visualization 1

HERMAN ET AL.: GRAPH VISUALIZATION AND NAVIGATION IN INFORMATION VISUALIZATION 1 Graph Visualization and Navigation in Information Visualization: a Survey Ivan Herman, Member, IEEE CS Society, Guy Melançon, and M. Scott Marshall Abstract—This is a survey on graph visualization and navigation techniques, as used in information visualization. Graphs appear in numerous applications such as web browsing, state–transition diagrams, and data structures. The ability to visualize and to navigate in these potentially large, abstract graphs is often a crucial part of an application. Information visualization has specific requirements, which means that this survey approaches the results of traditional graph drawing from a different perspective. Index Terms—Information visualization, graph visualization, graph drawing, navigation, focus+context, fish–eye, clustering. involved in graph visualization: “Where am I?” “Where is the 1 Introduction file that I'm looking for?” Other familiar types of graphs lthough the visualization of graphs is the subject of this include the hierarchy illustrated in an organisational chart and Asurvey, it is not about graph drawing in general. taxonomies that portray the relations between species. Web Excellent bibliographic surveys[4],[34], books[5], or even site maps are another application of graphs as well as on–line tutorials[26] exist for graph drawing. Instead, the browsing history. In biology and chemistry, graphs are handling of graphs is considered with respect to information applied to evolutionary trees, phylogenetic trees, molecular visualization. maps, genetic maps, biochemical pathways, and protein Information visualization has become a large field and functions. Other areas of application include object–oriented “sub–fields” are beginning to emerge (see for example Card systems (class browsers), data structures (compiler data et al.[16] for a recent collection of papers from the last structures in particular), real–time systems (state–transition decade). -

Toward Unified Models in User-Centered and Object-Oriented

CHAPTER 9 Toward Unified Models in User-Centered and Object-Oriented Design William Hudson Abstract Many members of the HCI community view user-centered design, with its focus on users and their tasks, as essential to the construction of usable user inter- faces. However, UCD and object-oriented design continue to develop along separate paths, with very little common ground and substantially different activ- ities and notations. The Unified Modeling Language (UML) has become the de facto language of object-oriented development, and an informal method has evolved around it. While parts of the UML notation have been embraced in user-centered methods, such as those in this volume, there has been no con- certed effort to adapt user-centered design techniques to UML and vice versa. This chapter explores many of the issues involved in bringing user-centered design and UML closer together. It presents a survey of user-centered tech- niques employed by usability professionals, provides an overview of a number of commercially based user-centered methods, and discusses the application of UML notation to user-centered design. Also, since the informal UML method is use case driven and many user-centered design methods rely on scenarios, a unifying approach to use cases and scenarios is included. 9.1 Introduction 9.1.1 Why Bring User-Centered Design to UML? A recent survey of software methods and techniques [Wieringa 1998] found that at least 19 object-oriented methods had been published in book form since 1988, and many more had been published in conference and journal papers. This situation led to a great 313 314 | CHAPTER 9 Toward Unified Models in User-Centered and Object-Oriented Design deal of division in the object-oriented community and caused numerous problems for anyone considering a move toward object technology. -

Infovis and Statistical Graphics: Different Goals, Different Looks1

Infovis and Statistical Graphics: Different Goals, Different Looks1 Andrew Gelman2 and Antony Unwin3 20 Jan 2012 Abstract. The importance of graphical displays in statistical practice has been recognized sporadically in the statistical literature over the past century, with wider awareness following Tukey’s Exploratory Data Analysis (1977) and Tufte’s books in the succeeding decades. But statistical graphics still occupies an awkward in-between position: Within statistics, exploratory and graphical methods represent a minor subfield and are not well- integrated with larger themes of modeling and inference. Outside of statistics, infographics (also called information visualization or Infovis) is huge, but their purveyors and enthusiasts appear largely to be uninterested in statistical principles. We present here a set of goals for graphical displays discussed primarily from the statistical point of view and discuss some inherent contradictions in these goals that may be impeding communication between the fields of statistics and Infovis. One of our constructive suggestions, to Infovis practitioners and statisticians alike, is to try not to cram into a single graph what can be better displayed in two or more. We recognize that we offer only one perspective and intend this article to be a starting point for a wide-ranging discussion among graphics designers, statisticians, and users of statistical methods. The purpose of this article is not to criticize but to explore the different goals that lead researchers in different fields to value different aspects of data visualization. Recent decades have seen huge progress in statistical modeling and computing, with statisticians in friendly competition with researchers in applied fields such as psychometrics, econometrics, and more recently machine learning and “data science.” But the field of statistical graphics has suffered relative neglect. -

Poster Summary

Grand Challenge Award 2008: Support for Diverse Analytic Techniques - nSpace2 and GeoTime Visual Analytics Lynn Chien, Annie Tat, Pascale Proulx, Adeel Khamisa, William Wright* Oculus Info Inc. ABSTRACT nSpace2 allows analysts to share TRIST and Sandbox files in a GeoTime and nSpace2 are interactive visual analytics tools that web environment. Multiple Sandboxes can be made and opened were used to examine and interpret all four of the 2008 VAST in different browser windows so the analyst can interact with Challenge datasets. GeoTime excels in visualizing event patterns different facets of information at the same time, as shown in in time and space, or in time and any abstract landscape, while Figure 2. The Sandbox is an integrating analytic tool. Results nSpace2 is a web-based analytical tool designed to support every from each of the quite different mini-challenges were combined in step of the analytical process. nSpace2 is an integrating analytic the Sandbox environment. environment. This paper highlights the VAST analytical experience with these tools that contributed to the success of these The Sandbox is a flexible and expressive thinking environment tools and this team for the third consecutive year. where ideas are unrestricted and thoughts can flow freely and be recorded by pointing and typing anywhere [3]. The Pasteboard CR Categories: H.5.2 [Information Interfaces & Presentations]: sits at the bottom panel of the browser and relevant information User Interfaces – Graphical User Interfaces (GUI); I.3.6 such as entities, evidence and an analyst’s hypotheses can be [Methodology and Techniques]: Interaction Techniques. copied to it and then transferred to other Sandboxes to be assembled according to a different perspective for example. -

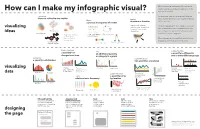

How Can I Make My Infographic Visual? Topic You’Ve Selected

When authoring an infographic, it is important to explore your data and ideas to make sense of the How can I make my infographic visual? topic you’ve selected. Explore how Visualizing can help you make sense of data and ideas are related to one another Explore ideas, and the following are some powerful ways to Explore structure or function explore your topic. a process or sequence of events Images with callouts, Once you’ve explored through visualizing, you will photographs, anatomical visualizing want to select some of the visualizations that best drawings, or scientific Tree diagram communicate what you believe is important, and ideas 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 illustrations Venn Diagram 2 include them in your infographic. Progressive depth or Timeline of related Cyclical diagram scale, image at historical events different levels of Ways of designing the overall look and feel of your magnification 3 infographic are included in the final section. Concept map or Branching Flowchart 1 network diagram Linear flowchart Explore if and how Add Explore if and how a quantity has an additional quantity a quantity is different in changed over time or category to a graph two or more different groups Explore how 3500 3500 60 Explore if and how 3000 50 3000 60 a quantity is distributed 40 50 2500 2500 30 40 two quantities are related 2000 30 2000 20 20 1500 10 1500 10 0 1000 0 1000 60 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 0 50 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 40 30 Timeline 3500 visualizing Timeline Dot Plot Bubble chart 20 Multiple -

Practical Data Visualization

Practical Data Visualization March 18, 2015 COMPSCI 216: Everything Data Angela Zoss Data Visualization Coordinator Data and Visualization Services WHY VISUALIZE? Preserve complexity Anscombe’s Quartet I II III IV x y x y x y x y 10.0 8.04 10.0 9.14 10.0 7.46 8.0 6.58 8.0 6.95 8.0 8.14 8.0 6.77 8.0 5.76 13.0 7.58 13.0 8.74 13.0 12.74 8.0 7.71 9.0 8.81 9.0 8.77 9.0 7.11 8.0 8.84 11.0 8.33 11.0 9.26 11.0 7.81 8.0 8.47 14.0 9.96 14.0 8.10 14.0 8.84 8.0 7.04 6.0 7.24 6.0 6.13 6.0 6.08 8.0 5.25 4.0 4.26 4.0 3.10 4.0 5.39 19.0 12.50 12.0 10.84 12.0 9.13 12.0 8.15 8.0 5.56 7.0 4.82 7.0 7.26 7.0 6.42 8.0 7.91 5.0 5.68 5.0 4.74 5.0 5.73 8.0 6.89 Preserve complexity Anscombe’s Quartet I II III IV x y x y x y x y Property Value 10.0 8.04 10.0 9.14 10.0 7.46 8.0 6.58 9 Mean of x 8.0 6.95 8.0 8.14 8.0 6.77 8.0 5.76 (exact) 13.0 7.58 13.0 8.74 13.0 12.74 8.0 7.71 Variance of x 11 (exact) 9.0 8.81 9.0 8.77 9.0 7.11 8.0 8.84 Mean of y 7.50 11.0 8.33 11.0 9.26 11.0 7.81 8.0 8.47 (to 2 decimal places) 14.0 9.96 14.0 8.10 14.0 8.84 8.0 7.04 4.122 or 4.127 Variance of y (to 3 decimal places) 6.0 7.24 6.0 6.13 6.0 6.08 8.0 5.25 4.0 4.26 4.0 3.10 4.0 5.39 19.0 12.50 Correlation between 0.816 x and y (to 3 decimal places) 12.0 10.84 12.0 9.13 12.0 8.15 8.0 5.56 y = 3.00 + 0.500x 7.0 4.82 7.0 7.26 7.0 6.42 8.0 7.91 Linear regression line (to 2 and 3 decimal places, 5.0 5.68 5.0 4.74 5.0 5.73 8.0 6.89 respectively) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anscombe%27s_quartet Preserve complexity Anscombe’s Quartet http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anscombe%27s_quartet Evaluate data quality Query using Facebook API • Node-link diagram Kandel, Heer, Plaisant, et al. -

Process Analysis Tools: Pareto Diagram (PDF)

Process Analysis Tools Pareto Diagram According to the “Pareto Principle,” in any group of things that contribute to a common effect, a relatively few contributors account for the majority of the effect. A Pareto diagram is a type of bar chart in which the various factors that contribute to an overall effect are arranged in order according to the magnitude of their effect. This ordering helps identify the “vital few” (the factors that warrant the most attention) from the “useful many” (factors that, while useful to know about, have a relatively smaller effect). Using a Pareto diagram helps a team concentrate its efforts on the factors that have the greatest impact. It also helps a team communicate the rationale for focusing on certain areas. This tool contains: Directions Sample Pareto Data Table and Diagram: Errors During Surgical Setup 1 Institute for Healthcare Improvement Boston, Massachusetts, USA Copyright © 2004 Institute for Healthcare Improvement Pareto Diagram Directions 1. Collect data about the contributing factors to a particular effect (for example, the types of errors discovered during surgical setup). 2. Order the categories according to magnitude of effect (for example, frequency of error). If there are many insignificant categories, they may be grouped together into one category labeled “other.” 3. Write the magnitude of contribution (for example, frequency of error) next to each category and determine the grand total. Calculate the percentage of the total that each category represents. 4. Working from the largest category to the smallest, calculate the cumulative percentage for each category with all of the previous categories. 5. Draw and label the left vertical axis with the unit of comparison (for example, “Number of Occurrences of Error,” from 0 to the grand total). -

Graphical Representation of Statistical Data

GRAPHICAL REPRESENTATION OF STATISTICAL DATA DR.S.ARULJOTHISELVI ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY PERIYAR GOVERNMENT ARTS COLLEGE 13.08.2020 1. BAR DIAGRAMS A Bar graph is a chart with rectangular bars with length proportional to the values that they represent. The bars can be plotted vertically or horizontally. One axis of the chart shows the specific categories being compared, and the other axis represents discrete values. A bar graph will have two axes. One axis will describe the types of categories being compared and the other will have numerical values that represent the values of the data. There are many different types of bar graphs. each type will work best with a different type of comparison. Simple bar diagram: It represent only one variable. for example sales,prodution,population figures etc..These are in same width and vary only in heights.It becomes very easy for readers to study the relationship.It is the most popular in practice. Sub divided bar diagram:While constructing such a diagram the various components in each bar should be kept in the same order.The components are shown with different shades or colours with a proper index. Multiple bar diagram: This method can be used for data which is made up of two or more components. In this method the components are are shown as separate adjoining bars. The components are shown by different shades and colours. Deviation bar diagram:Diviation bars are used to represent net quantities- excess or deficit, for example net profit, net loss,etc.it have negative and positive values. -

Data Visualization Options in Insights

Change: process through which something becomes Distribution: the arrangement of phenomena, could be different, often over time numerically or spatially A bar graph uses either horizontal or vertical bars to show Histograms show the distribution of a numeric variable. Data type: Qualitative Quantitative Temporal comparisons among categories. They are valuable to The bar represents the range of the class bin with the identify broad differences between categories at a glance. height showing the number of data points in the class bin. Measure: ascertain the size, amount, or degree of (something) A heat chart shows total frequency in a matrix. Using a A box plot displays data distribution showing the median, temporal axis values, each cell of the rectangular grid are upper and lower quartiles, min and max values and, outliers. A bar graph uses either horizontal or vertical bars to show symbolized into classes over time. Distributions between many groups can be compared. comparisons among categories. They are valuable to identify broad differences between categories at a glance. Bubble charts with three numeric variables are multivariate A choropleth map allows quantitative values to be mapped charts that show the relationship between two values while by area. They should show normalized values not counts A treemap shows both the hierarchical data as a proportion a third value is shown by the circle area. collected over unequal areas or populations. of a whole and, the structure of data. The proportion of categories can easily be compared by their size. Graduated symbol maps show a quantitative difference Graduated symbol maps show a quantitative difference between mapped features by varying symbol size.