University of Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Download of Kalle Mattson’S “Darkness” from the Ottawa Viral Sensation’S Doug Mclean (Pictured Here) Is Joined on the Cover New 7”

Free. Weekly. 7 // Issue 68 // Volume Weekly. Free. o ctober 17 ctober THE reunion ISSUE The BONADUCES RETURN with their first new music since ‘98 LIKE TO KNIT? STITCh ‘N BITCH IS FOR YOU STUDENTS IN DEBT: YOUR PROBLEMS ARE (KINDA) S OLVED Michael Feuerstack anita Daher Mariachi Ghost The official s TudenT new spaper of The universiTy of winnipeg the uNIter // october 17, 2013 03 EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN. When Winnipeg melodic-punk heroes The Bonaduces reunited a few years ago, there were no plans for anything big, other than just playing for fun. Now, for the first time since the band’s landmark 1998 record- ing The Democracy of Sleep, the beloved four piece is releasing something new. It’s just a digital single, something the band is attempting to sell short (how very Rob Gordon of them), but even still it’s exciting. Managing Editor Nicholas Friesen had a chat with the band’s Doug McLean and his label cohort Shad Bas- sett about their collective, Parliament of Trees, and all things Bonaduces. We’ve also got interviews with the art rock monster that is Mariachi Ghost, ex-Snailhouse troubadour Michael Feuerstack, reviews of Gravity and Casting By, as well as a piece about how knitting is bad ass. Stay cool, Winnipeg. online exclusives This week, check out The Next Reel, with a behind the scenes look at Greg Macpherson’s new video for “1995”, which was made by our own Nicholas Friesen and Daniel Crump. on the cover you can grab a free download of Kalle Mattson’s “Darkness” from the Ottawa viral sensation’s Doug McLean (pictured here) is joined on the cover new 7”. -

MAKEOUT Vldeotape

// SUPPORTING Vancouver’s independent THAT MAD AT LINDSEY FOR NOT PARTYING MAGAZINE FROM CiTR 101.9 FM MUSIC COMMUNTY FOR OVER 25 YEARS MAKEOUT VIDEOTAPE CAITLIN GALLUPE / HIDDEN TOWERS / HALF CHINESE / NEVER ON A SUNDAY PT.3 / KIDNAP KIDS! / THE OLYMPICS / THE FUNDRAISER / CHIN INJETI / SALAZAR / A TRIP TO CITY HALL 1 EDITOR editor’s note Jordie Yow Dear Discorder: ART DIRECTOR Well, by the time you read this the Olympics will be You will notice a band by the name of Makeout Videotape Lindsey Hampton upon us and our city will be swarmed with tourists here on the cover of this issue. The photo-ish image was taken for the biggest two-week party in the world. Maybe you are by Robert Fougere, who we think did a lovely job of getting PRODUCTION MANAGER even one of those tourists, in which case, “Hello tourist, all three band members into the shot. Debby Reis we are conflicted about you being here.” Perhaps the most important announcement that COPY EDITORS The Olympics are a mixed blessing at best, and they’ll we’re making this issue can be found on page 19. To keep Liz Brant, Corey Ratch, Debby Reis, always be a contentious one. For Vancouver’s music fans Discorder in print and continue informing you of what’s Miné Salkin, Al Smith they certainly have some benefits. There are plenty of acts going on in Vancouver’s independent music scene, we’re that will be coming to town and you will get the rare chance having a fundraiser. We’ve asked a number of our favourite AD MANAGER to see them play for free. -

Volume 40 - Issue 23 - Friday, April 15, 2005

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Spring 4-15-2005 Volume 40 - Issue 23 - Friday, April 15, 2005 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 40 - Issue 23 - Friday, April 15, 2005" (2005). The Rose Thorn Archive. 243. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/243 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROSE-HULMAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY T ERRE HAUTE, INDIANA Friday, April 15, 2005 Volume 40, Issue 23 News Briefs Another day at the fair Bridget Mayer fore this career fair by students RA selection Staff Writer who had submitted resumes to companies through the Ca- fi nalized Employers at Wednesday’s reer Services’ online eRecruit- career fair had just one thing ing program. -

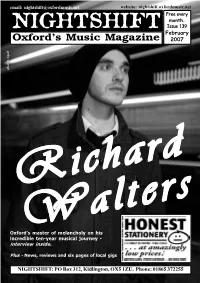

Issue 139.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 139 February Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 photo by Squib RichardRichardRichard Oxford’sWaltersWaltersWalters master of melancholy on his incredible ten-year musical journey - interview inside. Plus - News, reviews and six pages of local gigs NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS photo: Matt Sage Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] BANDS AND SINGERS wanting to play this most significant releases as well as the best of year’s Oxford Punt on May 9th have until the its current roster. The label began as a monthly 15th March to send CDs in. The Punt, now in singles club back in 1997 with Dustball’s ‘Senor its tenth year, will feature nineteen acts across Nachos’, and was responsible for The Young six venues in the city centre over the course of Knives’ debut single and mini-album as well as one night. The Punt is widely recognised as the debut releases by Unbelievable Truth and REM were surprise guests of Robyn premier showcase of new local talent, having, in Nought. The box set features tracks by Hitchcock at the Zodiac last month. Michael the past, provided early gigs for The Young Unbelievable Truth, Nought, Beaker and The Stipe and Mike Mills joined bandmate Pete Knives, Fell City Girl and Goldrush amongst Evenings as well as non-Oxford acts such as Buck - part of Hitchcock’s regular touring others. Venues taking part this year are Borders, Beulah, Elf Power and new signings My band, The Venus 3 - onstage for the encores, QI Club, the Wheatsheaf, the Music Market, Device. -

Safewalk Service Use Increased Eightfold Want to Cover the News? Senc Cin Email

// Page 2 iiwBS EVENTS II THISWEEK, CHECK! OUR CAMPUS // ONE ON ONE WITH THE PEOPLE AND BUILDINGSTHAT MAKE UBC THURSDAY ' 9 March 27th 8pm Koerner Plaza EVENT POS WC Featuring NomNcm. Luc Briede-Caoper and G-silenl (rum UBC EDM UTOWN@UBC , UNA! [<^©"RPVRA BIKE RAVE 8:00 P.M. @ KOERNERPLAZA Go for a loud and adventurous ride around campus on your decked out scooter, skateboard or bicycle. Best decorated ride gets a free ticket to Block Party. Featuring glowsticks, energy drinks and spinnin' local DJs. Free THURSDAY' 9 =HOTO CHERIHAN HASSUN/THE UBYSSEY STARGAZING The Syrup Trap brings (sometimes not-so) subtle satire to the Canadian masses. 6:30 P.M. @IKB256 Take advantage of U BC's clear skies and both expert and amateur astron omers by joining the U BC Astronomy Club for a night of stargazing and The Syrup Trap wants to take their satire national space facts. A professional-grade telescope will be on site. Free Jack Hauen abandoned their west coast projects that are sustained Sports & Rec Editor roots (just Tuesday afternoon purely by enthusiasm never last. FRIDAY ' 10 If you're a UBC student, you're they published an account of a "I'm really excited by the idea already aware of the Syrup Trap. 41 bus that probably crashed). of building not just a blog, but a And if you aren't, you've almost But Zarzycki and his crew feel magazine." definitely heard of their articles. that they've honed their skills "Time costs money whether The talented group of satirists enough to make a go of becom or not you think it costs you were the ones who convinced ing Canada's Onion. -

Shine a Light: Surveying Locality, Independence, and Digitization in Ottawa’S Independent Rock Scene

Shine a Light: Surveying Locality, Independence, and Digitization in Ottawa’s Independent Rock Scene by Michael Robert Audette-Longo A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Michael Audette-Longo ii Abstract This dissertation examines the articulation and reconfiguration of locality in Ottawa's independent (indie) rock scene. It argues that styles of producing and relating to indie music that have been traditionally embedded in local scenic activity and practices of “do it yourself” (DIY) have been translated into more ubiquitous, quotidian, and valuable metadata and labour that organizes and powers the operations of disparate digital media sites, including digital music services like Bandcamp, CBC Radio 3, and Wyrd Distro. This argument is developed through closer analyses of the following case studies: the entrepreneurial strategies and musical focuses of Ottawa-based independent record labels Kelp and Bruised Tongue Records; scene-bound media like zines, blogs, music video and campus/community radio; the re-articulation of local regions as metadata that organize the search and retrieval functionalities of the digital music streaming services CBC Radio 3 and Bandcamp (a particular iteration of local regions I dub the “indexi-local”); and the concurrent incorporation of DIY labour and reconfiguration of the business of independent music evident in the digital music retailers Bandcamp and Wyrd Distro. This project contends that in the midst of digitization, the media sites, entrepreneurial strategies, and subcultural practices traditionally folded into the production of independence in local indie music scenes persist. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • OST – Fifty Shades of Grey – the Remixes • Good Lovelies – Burn the Plan • Various Artists –

OST – Fifty Shades Of Grey – The Remixes Good Lovelies – Burn The Plan Various Artists – Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI15-19 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 *Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Brandon Flowers/ The Desired Effect Cat. #: B002299002 Price Code: JSP Order Due: April 23, 2015 Release Date: May 19, 2015 File: Alternative Genre Code: 2 Box Lot: 25 Bar Code: Key Tracks: 1. Dreams Come True 6. Lonely Town 2. Can’t Deny My Love 7. Digging Up The Heart 3. I Can Change 8. Never Get You Right 6 02547 26544 9 4. Still Want You 9. Untangled Love 5. Between Me And You 10. The Way It’s Always Been SHORT SELL Key Points: Almost five years since the release of his critically acclaimed solo debut, Flamingo, Flowers’ solo return follows a time of continued huge success with his band The Killers. As Flowers announced in a hand-written note via www.brandonflowersmusic.com earlier, he has been working with the producer Ariel Rechtshaid (Haim, Vampire Weekend, Charlie XCX), with recording taking place at The Killers’ own Battle Born studios in Las Vegas. Also Available: Artist/Title: Brandon Flowers/ Flamingo Cat#: B001474502 Price Code: JSP UPC#: 602527487496 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Island Territory: International Release Type: O For additional artist information please contact Karolina Charczuk at 416‐718‐4153 or [email protected]. UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Zedd / True Colors Cat. -

Collectivity, Capitalism, Arts & Crafts and Broken Social Scene

“A BIG, BEAUTIFUL MESS”: COLLECTIVITY, CAPITALISM, ARTS & CRAFTS AND BROKEN SOCIAL SCENE by Ian Dahlman Bachelor of Arts (Hons.), Psychology and Comparative Literature & Culture University of Western Ontario, 2005 London, Ontario, Canada A thesis presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2009 © Ian Dahlman 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59032-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59032-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

1995 Fall Program Guide

~Dnfs@@ ~© @®K§ ®@@ @®@@§o ®@@ OO©K@ o o o hJ I ~ @ ~ p [§s I @J @ ~ ~ ~ @J c:::::, \C ro=-. ~ ~ @ \C ~o Fl Ul ~ Ci@ ~ ~ ~ ~ @8 (1 ~o 0~ -e ~ ~ =~ 00 I ~o=-· z ro CIQ ~ c:::::, e ~ ~ ~ @'j) ~ &J I 1 =e, @ = 1 @ I = e, ~ ~ 9 ~ ~ '< ~o 0~ @ &J ~ @) ~ L7@c2®~111 ~@~®cir ®LQ]~ L7Jlc2@~@®~ Lhlh~~ LQ]~ 100 • ', WM C N. ·')~·,.:'. .. 91. 7 FM Clc1-,:-p . :: .. Ct.. o.. FF. • .. ::... ~••s:. '1-·· ··' C....,KrE . .· .. ·.,.· · 1'\.,::) WMCN Executive Staff Fall 1995 General Manager Promotions Director New Music Directors Chris Herrington Pete Bayard Joanna Curtis Eric Hausken News/PSA Directors Assistant Promotions Directors Kara Fiegenschuh Jenni Undis Michelle Hayes Hip Hop Director Curtis Stauffer Jenny Ahern MattArlyck Style Consultant/Live Bands World/Reggae Director Jazz/Blues Director Peter "Tigger" Lunney Kyan Thornton Abe Wheeler Production Assistant Metal Director Country Director Mike Storey Mike Hourigan Nate Sparks Office Manager Engineer Cory Walker Ethan Torrey ~ ~ cqi ll11 (9 ~ 1t IL fl Iffi (9 Macalester College (Q)~(O)=(O)] li 2 1600 Grand Ave. (Q)ffn~t9 IL1tiffit9 St. Paul, MN, 55105 Co)~ (0) = (0) (0) ~2 2 Who we are and what we do: a listener's guide i. I'm Chris Herrington, the general manager Our other special block is World/R&B from 6-8 of WMCN, and I'd like to welcome you to p.m. weekdays. From Dancehall to African to H another great year of broadcasting at the best, Caribbean to Ska to R&B, it's all here. Kyan Thornton's if least recognized, radio station in the Twin Cities. -

Topeka-AUG-2019

Topeka EDITION includes Lawrence, Manhattan, Emporia & Holton FREE! NE! The Area’s Most Complete Event Guide TAKE O Entertainment PAGE 16 HARVEY HOUSE LUNCHEON Page 13 CELEBRATING FAIT H, FAMILY AND COMMUNITY IN NORTHEAST KANSAS facebook /metrovoicenews Celebrating our 13th year! VISIT US AT or metrovoicenews.com VOLUME 13 • NUMBER 12 August 2019 TO ADVERTISE, CONTRIBUTE, SUBSCRIBE OR RECEIVE BULK COPIES, CALL 785-235-3340 OR EMAIL [email protected] NEW RESIDENT Christian Education church guide How to teach your kids Summit to take up First Southern Baptist where Sunday Church School left off to live a healthy lifestyle Dr. Don Davis See inside back cover! Great Expectations At its roots, the Sunday School move - in Marriage? ment was a response to the need for edu - cation for children who worked in facto - ries all week and found themselves aimless, uneducated and without purpose on Sundays. Urban families embraced the ini - by Calah Alexander them to the park — sometimes. But born, I reached the end of my rope. I tiative and benefactors helped it flourish. those were supplementary additions was tired of my kids fighting over the When public education took hold, the Five years ago, our family lifestyle to our unhealthy, sedentary lifestyle. remote, tired of my clothes not fit - movement focused its efforts on teaching was not healthy. We ate dessert every A lifestyle that was making all of us ting, and tired of feeling so dang the Story of God, and remained one of the night and spent so much time in unhealthy, lazy, and miserable. tired. -

Artsnews SERVING the ARTS in the FREDERICTON REGION April 5, 2018 Volume 19, Issue 13

ARTSnews April 5, 2018 Volume 19, Issue 14 ARTSnews SERVING THE ARTS IN THE FREDERICTON REGION April 5, 2018 Volume 19, Issue 13 In this issue *Click the “Back to top” link after each notice to return to “In This Issue”. Upcoming Events 1. Mental Health: A Load off the Mind in the Yellow Box Gallery 2. Theatre UNB presents A Patriot for Me by John Osborne Apr 4-7 3. 4th Annual UNB MWC Pow-Wow 4. Music Runs Though It presents Evan LeBlanc (David in the Dark) at Corked Wine Bar Apr 5 5. Perspective at the Open Space Theatre Apr 6 6. The Archaeological Institute of America Society presents Terracotta Warriors of China Apr 6 7. St. Thomas University Seminar in Directing Class presents An Evening of Short Plays Apr 6 & 7 8. Upcoming Events at Grimross Brewing Co. Apr 6-18 9. House Concert with Shawna Caspi Apr 7 10. Comedy at Charlotte Street Arts Centre Apr 7 11. Adult Literacy Fredericton Happy Booker Fundraiser Apr 7 12. MusicUNB Progressions Series presents The Collection Apr 8 13. The Fredericton Concert and Marching Band present a Spring Concert Apr 9 14. Book Launch for David Adams Richards’ New Novel Mary Cyr Apr 9 15. From The Girl on the Bus to India’s Daughter Apr 9 16. Monday Night Film Series presents The Shape of Water (Apr 8 & 9) & I, Tonya (Apr 16) 17. Art Party 0410: The Old Dory at Unplugged Board Game Café Apr 10 18. Rosie & The Riveters Aim to Empower with Vintage-Inspired Folk Music at The Playhouse Apr 11 19.