The Bahmanis of Gulbarga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

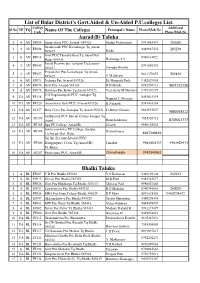

All Colleges List of Bidar Dist (Updated)21.09.2016. (1).Xlsx

List of Bidar District's Govt.Aided & Un-Aided P.U.colleges List. College Additional Sl.No. TP TQ Principal's Name Phone/Mob No Code Name Of The Colleges Phone/Mob No Aurad(B) Taluka 1 A AU FF005 Amareshvar PUC Avarad -585326 Gudda Vishwanath 9741084337 280060 Shantivardk PUC Kamalnagar Tq Aurad- 2 A AU FF008 9448947525 285239 585417 Rikke Govt PUC Thanakushnor Tq Aurad Dist 3 G AU FF018 9740314922 Bidar-585436 Halmadge S S Janath Praveen puc santapur Tq Santpur- 4 A AU FF040 9741999353 585421 Zareppa Beladar Priyadrshni Puc Kamalnagar Tq Aurad- 5 A AU FF057 9611170651 285830 585417 V.M.Swamy 6 A AU FF071 Nalanda Puc Avarad-585326 Dr.Manmath Dole 9482659001 7 G AU FF076 Govt Puc Avarad-585326 B N Shinde 9742704713 9611222136 8 A AU FF078 Haralaya Puc Kouta Tq Aurad-585421 Veershetty M Shivshetty 9449140177 S G Nagamarapalli PUC wadagnv Tq 9 UA AU FF118 9483015319 Aurad Nagnath L Niranjan 10 UA AU FF120 Amareshvar Girls PUC Avarad-585326 K.Nagnath 9743414268 11 UA AU FF157 Holy Cross Puc Santapur Tq Aurad-585421 Fr.Roque Dsouza 9845833657 9880053512 Jai Bhavani PUC Shivaji Colony Santpur Tq 12 UA AU FF170 7026320711 Aurad Ramchandrarao 8749017777 13 UA AU FF185 Iqra PU College, Aurad(B). Ganesh 9880155025 Siddarameshwar PU College, Santpur, 14 UA AU FF188 Naveelkumar Tq:Aurad, Dist: Bidar. 8197249143 Sri Sri Sri sant Sevalal PUC 15 UA AU FF200 Dongargaov Cross Tq:Aurad(B) Janabai 9880402333 9561929333 Dt:Bidar 16 UA AU FF207 Patriswamy PUC, Aurad(B) Chandrakala 9742940661 Bhalki Taluka 1 A BL FF007 C.B Puc Bhalki-585328 V.S.Kattimani 9449139146 262243 2 A BL FF013 Shivaji Puc Bhalki-585328 M.D.Patil 9448745877 3 G BL FF026 Govt Puc Halabarga Tq Bhalki-585413 Shivaraj Patil 9986522463 4 A BL FF031 Satyniketana Puc Bhalki-585328 R G Mahajan 9740744883 260070 5 A BL FF034 MRA Puc Janta Colony Bhalki-585328 R P More 9901519343 9480298497 6 A BL FF047 Akkamahadevi Puc Bhalki-585328 Savitri Maroorkar. -

Bidar District “Disaster Management Plan 2015-16” ©Ãzàgà F¯Áè

BIDAR DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2015-16 Government of Karnataka Bidar District “Disaster Management Plan 2015-16” ©ÃzÀgÀ f¯Áè “““«¥ÀvÀÄÛ“«¥ÀvÀÄÛ ¤ªÀðºÀuÁ AiÉÆÃd£É 20152015----16161616”””” fĒÁè¢üPÁjUÀ¼À PÁAiÀiÁð®AiÀÄ ©ÃzÀgÀ fĒÉè BIDAR DEPUTY COMMISSIONER OFFICE, BIDAR. BIDAR DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2015-16 CONTENTS SL NO TOPIC PAGE NO 1 Preface 03 2 Glossary 04 3 Chapter-1 :Introduction 05-13 4 Chapter-2 : Bidar District Profile 14-25 5 Chapter-3 : Hazard Risk Vulnerability and Capacity (HRVC) 26-41 Analyses 6 Chapter-4 : Institution Mechanism 42-57 7 Chapter-5: Mitigation Plan 58-73 8 Chapter-6: Response Plan 74-80 9 Chapter-7: Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 81-96 10 Chapter-8 : Resources and Contact Numbers 97-117 11 Chapter-9 : Standard Operating Processor (SOPs) 118-125 12 Chapter-10 : Maps 126-137 13 Conclusion 138 14 Bibliography 139 BIDAR DEPUTY COMMISSIONER OFFICE, BIDAR. Bidar District Disaster Management Pla n 2015-16 Office of the Deputy Commissioner Bidar District, Bidar Shri. Anurag Tewari I. A.S Chairman of Disaster Management & Deputy Commissioner Phone: 08482-225409 (O), 225262(Fax) Bidar District E-mail: [email protected] PREFACE “Disaster” means unforeseen and serious threat to public life with suddenness in terms of time. Declaration of disaster depends on gravity or magnitude of situ ation, number of victims involved, time factor i.e. suddenness of an event, non- availability of medical care in terms of space, equipment’s medical and pa ramedical staff, medicines and other basic human needs like food, shelter and clothing, weather conditions in the locali ty of incident etc., thus enhancing human sufferings and create human needs that the victim cann ot alleviate without assistance. -

Land Identified for Afforestation in the Forest Limits of Bidar District Μ

Land identified for afforestation in the forest limits of Bidar District µ Mukhed Nandijalgaon Bawalgaon Mailur Tanda Tanda Muttakhed Chikhli Hangarga Buzurg Hokarna Tanda Tanda Aknapur Sitalcha Tanda Sawargaon Ganganbid Dapka Kherda Buzurg Ganeshpur Bonti Lingi Talab Tanda Wagangiri Doparwadi Bada Tanda Handikheda Tanda Kurburwadi Hulyal Tanda Handikheda Murki Tanda Chemmigaon Shahpurwadi Wanbharpalli Malegaon Tanda Hulyal Manur Khurd Malegaon Donegaonwadi Dongargaon Badalgaon Hakyal Dhadaknal Bhopalgad Ekamba Sangnal Nandyal Nagmarpalli Karanji Kalan Karanji Khurd Madhur Sindyal Narayanpur Dongaon Belkoni Karkyal Jaknal Ganeshpur Khelgaon Aknapur Bijalgaon Jamalpur Aurad Sundal Itgyal Mamdapur Raipalli Indiranagar Tanda Kamalanagara Tegampur Kotgial Kindekere Yengundi Lingdhalli Rampur Khasimpur Tornawadi Mudhol Tanda Murug Khurd Kamalnagar Torna Hasikera Wadi Basavanna Tanda Balur Mudhol Buzurg Naganpalli Yeklara Chintaki Digi Tuljapur Gondgaon Kollur Munganal Bardapur Munanayak Tanda Boral Beldhal Mudhol Khurd Holsamandar Lingadahalli Ashoknagar Bhimra Mansingh Tanda Aurad Chandeshwar Mahadongaon Tanda Horandi Korial Basnal Eshwarnayak Tanda Jonnikeri Tapsal Korekal Mahadongaon Lingadahalli Lingadahalli Tanda Yelamwadi Sawali Lakshminagar Kappikeri Sunknal Chandpuri Medpalli Chandanawadi Ujni Bedkonda Gudpalli Hippalgaon Maskal Hulsur Sonali Gandhinagar Khed Belkuni Jojna Alwal Sangam Santpur Mankeshwar Kalgapur Nande Nagur Horiwadi Sompur Balad Khurd Kusnur Maskal Tanda M Nagura Chikli Janwada Atnur Balad Buzurg Gangaram Tanda Jirga -

Humnabad Bar Association : Humnabad Taluk : Humnabad District : Bidar

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : HUMNABAD BAR ASSOCIATION : HUMNABAD TALUK : HUMNABAD DISTRICT : BIDAR SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE VEERAPANNA A MYS/16/58 1 S/O BASWANAPPA AGDI AGDI GALLI HUMNABAD HUMNABAD BIDAR 585 330 SYED ABDUL WAZEED QAMAR MYS/92/63 2 S/O SHRI HAJI SYED ISMAIL SAHEB H.NO.13-130 NEW BI GALLI TOWN HUMNABAD BIDAR 585 330 PATIL PRABHU SHETTY RACHAPPA MYS/227/74 3 S/O RACHAPPA POST UDUMMALLI HUMNABAD BIDAR 585401 MOHD. ISMAIL AHMED KAR/250/77 4 S/O SHAIK MEHBOOBSAB H.NO.11-73 , TOPE GALLI , HUMNABAD HUMNABAD BIDAR 585 330 1/22 3/17/2018 BHALKIKAR ARVIND GANESH RAO KAR/304/77 5 S/O GANESH RAO H BHALKIKAR AT PO: MANIKNAGAR, HUMANABAD HUMNABAD BIDAR PATIL VEERANNA KANTEPPA KAR/449/80 S/O KANTEPPA PATIL 6 NEAR OLD DEGREE COLEGE, M.U.S.S. ROAD, HUMANABAD HUMNABAD BIDAR 585330 BIRADAR MADHAVA RAO KAR/187/81 7 S/O MADIVALAPPA R/O HUMNABAD HUMNABAD BIDAR 585 330 CHITGOPKAR SRIKANT KRISHNARAO KAR/541/81 8 S/O KRISHNA RAO CHITGOPKAR KATHADI ROAD , HUMNABAD HUMNABAD BIDAR 585330 KULKARNI AMBADAS RAO MANOHAR RAO KAR/522/83 9 S/O MANOHER RAO LIG 24, KHB COLONY ,HUMANABAD HUMNABAD BIDAR 2/22 3/17/2018 KADAMBAL BASAVARAJ KAR/560/85 S/O NARASAPPA 10 VEAR DR GOURAMMA HOSPETAL, BASAVA NAGAR. HUMNABAD BIDAR 585 330 NOOLA SHANTAPPA SHARANAPPA KAR/622/85 11 S/O SHARANAPPA GADAWANTI HUMNABAD BIDAR 585353 MALI PATIL ASHOK BASAVANTH RAO KAR/237/87 S/O BASAVANTH RAO 12 NO.20-647/33, VEERBADRESHWARA HUMMADBAD HUMNABAD BIDAR 585 330 CHILVANTH UDAY KUMAR SHANKAREPPA KAR/679/87 13 S/O SHANKAREPPA CHILVANTH NO25-323 ,SHIV NAGAR ,HOMANABAD HUMNABAD BIDAR MOHD. -

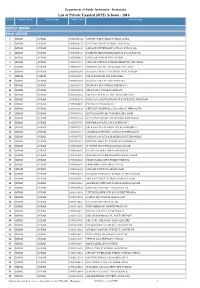

Department of Public Instruction - Karnataka List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No

Department of Public Instruction - Karnataka List of Private Unaided (RTE) Schools - 2016 Sl.No. District Name Block Name DISE Code School Name Distirct :BIDAR Block :AURAD 1 BIDAR AURAD 29050100124 LITTLE STAR PUBLIK SCHOOL AURA 2 BIDAR AURAD 29050100137 SATYAM PUBLIC SCHOOL AURAD(B) 3 BIDAR AURAD 29050100159 SARASWATI PRIMARY SCHOOL AURAD (B) 4 BIDAR AURAD 29050100169 PATRISWAMY INTERNATIONAL P.S AURAD (B) 5 BIDAR AURAD 29050100401 SANGAMESHWAR HPS ALUR(B) 6 BIDAR AURAD 29050101212 SARASWATHI LPS SCHOOL BELKUNI (CH) CROSS 7 BIDAR AURAD 29050101501 VISHWACHETAN LPS SCHOOL BALAT(K) 8 BIDAR AURAD 29050102004 BALAJI GURUKUL LPS BELKUNI(B) AURAD 9 BIDAR AURAD 29050102707 OM SARASWATI LPS CHINTAKI 10 BIDAR AURAD 29050102709 BASAVA CHETAN LPS CHINTAKI 11 BIDAR AURAD 29050103701 JIJAMATA LPS SCHOOL DHABKA(C) 12 BIDAR AURAD 29050103805 SRI SWAMY VIVEKANAND LPS 13 BIDAR AURAD 29050103902 SRI SANT SEVALAL PRY DONGARGAON 14 BIDAR AURAD 29050104104 POOJYA NAGLING SWAMY D K GURUKUL DONGAON 15 BIDAR AURAD 29050105409 PRANALI LPS HOKRANA 16 BIDAR AURAD 29050105804 SHIVALINGESHWARA LPS SCHOOL HEDGAPUR 17 BIDAR AURAD 29050107102 BHUVANESHWARI GURUKUL HPS JAMB 18 BIDAR AURAD 29050107502 BHUVANESHWARI LPS SCHOOL KARANJI(B) 19 BIDAR AURAD 29050107906 MANIKRAO PATIL LPS KUSHNOOR T 20 BIDAR AURAD 29050107913 SRI KANTEPPA GEERGA LPS KUSHNOOR(T) 21 BIDAR AURAD 29050107914 S.B.BHARATI PUBLIC SCHOOL KUSHNOOR(T) 22 BIDAR AURAD 29050107915 SARSAWATI VIDYA MANDIR LPS KUSHNOOR(T) 23 BIDAR AURAD 29050107916 ORCHID CONCEPT SCHOOL KUSHNOOR (T) 24 BIDAR AURAD 29050108009 -

SENIOR CIVIL JUDGE and JMFC,HUMNABAD SARASWATHI DEVI SENIOR CIVIL JUDGE Cause List Date: 04-09-2020

SENIOR CIVIL JUDGE AND JMFC,HUMNABAD SARASWATHI DEVI SENIOR CIVIL JUDGE Cause List Date: 04-09-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate 01:00-02:00 PM 1 M.C. 46/2019 Channareer so Chandrakanth TUMBA (JUDGMENTS) Choukimath SHREEDHAR Vs MANIKAPPA Shruti wo Channareer Choukimath CHITKOTE CHANNAPPA SHIVRAJ 11:00-12:00 AM 2 O.S. 23/2013 Smt. Shankramma D.M advocate (SUMMONS) Vs The of karnataka Through Dy. AGP commissioner 3 O.S. 21/2020 Prayagbai W/O Madivalappa R/O S.B.Munsi Adv (NOTICE) Rajeshwar Tq B. Kalyana Vs Mallappa S/O Basavanappa Kallur R/O Rajeshwar Tq B.Kalyana 4 G and WC 10/2020 Medha D/o Baburao Tirlapur age Ravikant K Hugar (NOTICE) 11 yrs, minor, u/g of Sharnappa Gadami S/o BaburaoGadami age 36 yrs Vs To Whom So ever it may concern 5 O.S. 27/2015 Ningappa so late mallappa KIRANKUMAR (EVIDENCE) dhanger @ ambapnour aged 60 S.HANAMSHETTY year occu agri ro bemalkhed tq humnabad A.G.P Vs The State of Karnataka Through Deputy Commissioner Bidar 6 O.S. 29/2015 Ameen Shah Fakeer so mastan KIRANKUMAR (EVIDENCE) shah fakeer darvesh aged abou S.HANAMSHETTY 80 year occ agri ro bemalkeda tq humnab A.G.P Vs The State of Karnataka Through Deputy Commissioner Bidar 7 Misc 3/2016 Pltff No 10 Baswaraj So Sri D Mahadevappa (EVIDENCE) Ramchander Arya 38 yrs Occ Adv Agri Vs A.G.P The State through Commissioner 1/4 SENIOR CIVIL JUDGE AND JMFC,HUMNABAD SARASWATHI DEVI SENIOR CIVIL JUDGE Cause List Date: 04-09-2020 Sr. -

Review of Research

Review of ReseaRch BIDAR DISTRICT AS A POTENTIAL TOURISM DESTINATION: CHALLENGES FROM MEDIA PERSPECTIVE Venkatesh Narasappa issN: 2249-894X impact factoR : 5.7631(Uif) Research scholar , Department of Journalism and Mass UGc appRoved JoURNal No. 48514 Communication , Gulbarga University, Kalaburagi. volUme - 8 | issUe - 8 | may - 2019 ABSTRACT: World Trade Organization has defined tourism as, activities of persons travelling to and staying in places outside of their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes. Tourism is travel for pleasure or business; also, the theory and practice of touring, the business of attracting, accommodating, and entertaining tourists, and the business of operating tours. Tourism includes the industry that package, facilitate, promote and deliver such travel and take care of those on the move and also influence the visitors and host communities for the mutual benefit of both. India is the land of two ancient civilizations like Indus valley civilization and Aryan civilization(UK essay, 2017). Planned and institutionalized effort on tourism started in India in from the early seventies. The development of tourism as an alternative revenue source is the new strategy in most countries because of its multiplier effect on other sectors of the economy, creating large volume of job for both skilled and unskilled labor. KEYWORDS: World Trade its sustained promotions and Sinnurganpathi opined that, like Organization , usual campaigns have finally created its backlog in socio-economic environment , Indus valley the the world sit up and take development, its tourism is civilization. notice of the ‘Many Worlds’ that additionally neglected and lacks make up this vibrant state (DOT, development. -

Notificat10nюfcontainme

NOTIFICAT10NЮ FCONTAINMENT ZONE DISTRICT BIDAR In view of power delegated to Chairperson,Bidar,District Disastcr Managemcnt Authority under National Disaster Management Act(NDMA)2005 by G.0.No.RD 157]R2020 and in exercise of the pOwers conferred under section 26,30 and 34 of NDMA, 2005, and Under relevant paras of notiflcation issucd undcr Epidemic E)isease Act,1897 by State Govenllnent, and As per dcflnition ofContainmcnt Zone vidc G.0。 No.HFW 109 ACS 2020 dated: 17-04-2020.I hereby declarc surrollnding 100 mtrs arca as an Activc Containmcnt Zone for Zone Zone Name Patients Conlirmed Incident Population Shops Houses No. Number Date Commander 72 KAMAL NAGAR P-118301,P… 130596 31-07… 2020 Tahsiidar 60 2 12 P-130504,P-130998 Kamalnagar 272 P-126443,P-129467 31-07-2020 Tahsiklar Bidar 55 2 14 BANK COLONY P-94538P… 126607 P-130958 308 SIDDI TALEEM BIDAR P-117260P-118033 01-08-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 80 2 16 P-122660P-123484 P-126585P-129432 P-140199 310 GUMPA BIDAR P-132579,P-132783 01-08-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 96 4 20 P-134527,P-134545 P-134569,P-135936 P-136171 337 NO■IBAD BIDAR P-124749,P-129263 31-07-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 78 3 20 つ 389346 J.P.NAGAR BIDAR P-137270 01-08-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 59 4 12 3・47 KAILASH NAGAR GUMPA P-129337,P-84514 31-07-2020 Tahs ldar Bidar 63 2 18 KHB COLONY BIDAR P-129375, 31-07-2020 Tahs ldar Bidar 69 4 22 1 352 VIDYA NAGAR COLONY BIDAR P-129326,P-129653 31-07-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 55 2 19 P-129654,P-129655 392 MANGALPET BIDAR P-135023,P-113069 28¨ 07-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 55 2 18 431 SP OFFICE BIDAR P-123426,P-123427 -

Indian Archaeology 1958-59 a Review

INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY 1958-59 —A REVIEW EDITED BY A. GHOSH Director General of Archaeology in India DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI 1959 Price Rs. 1000 or 16shillings COPYRIGHT DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRINTED AT THE CORONATION PRINTING WORKS, DELHI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This sixth number of the annual Review tries to embody, like its predecessors, information on all archaeological activities in the country during the previous year. The varied sources of information are obvious in most cases: where they are not, they have, as far as possible, been suitably acknowledged. From the ready and unconditional response that I have all along been receiving to my request for material, it is obvious that it is realized at all quarters that the Review has been performing its intended function of publishing, within the least possible time, the essential archaeological news of the country. At the same time, as it incorporates news obtained from diverse sources, the assumption of responsibility by me, as the editor, for the accuracy of the news, much less of the interpretation thereof, is precluded. My sincerest thanks are due to all—officers of the Union Department of Archaeology and of the State Governments, heads of other organizations concerned with archaeology and individuals devoting themselves to archaeological pursuits— who have furnished me with material that is included in the Review and to those colleagues of mine in the Department who have assisted me in editing it and seeing it through the press. New Delhi: A. GHOSH The 10th September 1959 CONTENTS PAGE I. General ... ... ... 1 II. -

5. Water Management System Under the Bahmanis and Barid Shahis– a Study of the Karez System and the Bagh-E-Hammam of Bidar

ISSN: XXXX-XXXX Volume 1, Issue 1; June 2021 International Journal of Research and Analysis in Humanities Web: https://www.iarj.in/index.php/ijrah 5. Water Management System under the Bahmanis and Barid Shahis– A Study of the Karez System and the Bagh-E-Hammam of Bidar Omkar Kallappa Ph.D Researcher, Department of History, Gulbarga University, Gulbarga. Karnataka. Dr. Vijaykumar Salimani Research Guide, and Principal, GFGC Chittapur, Kalaburagi, Karnataka. ABSTRACT Human civilization across the world stands as a testimony that water is one of the major necessities from points of nature. The confrontations with nature especially in drier areas revolve around ground water, whether harnessing, transporting, usage or management and many inventive ideas were born, for the purpose in the drier parts of the globe. Hence, several methods of water extraction, collection and management are invented throughout the globe, some of which are associated with efficient, sustained use of surface water, ground water and rain water. Karez is one such inventive method of collection, transportation, storage and distribution of ground water. The most unique features of Bidar is this historic water supply system, called Karez, (also known as qanat). KEYWORDS Water, Water Management, Water Management System, Bahmanis and Barid Shahis, Karez System, Bagh-E-Hammam. Introduction: Muslim dynasties with ruling class descending from Persia or having influential Karez is an inventive method of collection, connections with Islamic world and inviting transportation, storage and distribution of expert engineers from there. Karez strongly ground water. Most of the Karez systems in influenced the village socio-economic India were developed during reign of organisations due to multitude of uses they were brought into. -

BIDAR Sec-4 NOTIFICATIONS Gazettee Sl

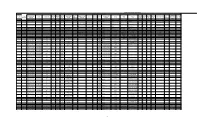

Revenue Sub Division: Basavakalyan BIDAR Sec-4 NOTIFICATIONS Gazettee Sl. No. Section-4 Govt. Area in Area in Area in Name of the CA / Section-17 Govt. Revenue Sub Survey Area in Area in Area in CA / Sl. No Date Survey Nos Date Division District Taluk Hobli Village Name of the Block Notification Page No. (Original) order No. Ha Ac Gu Block Non CA Order No Division No Ha. Ac Gu Non CA Date 1 1 AHFF 226 FAF 88 03-08-1994 23 63 155 673 Hokrana BIDAR BIDAR BIDAR Hokrana AHFF 226 FAF 88 03-08-1994 84 42 103 782 BIDAR BIDAR BIDAR Hokrana Mirajwadi Block A 2 2 FEE 78 FAF 2006 13-08-2008 BIDAR BIDAR AURAD Mirajwadi 33 5.16 12 75 & B Mirajwadi Block A FEE 78 FAF 2006 13-08-2008 BIDAR BIDAR AURAD Mirajwadi 43 3.14 7 75 & B 3 2 AHFF 53 FAF 91 28-06-1991 17/1 7.82 19 323 Sangama Block BIDAR BIDAR AURAD Kushanuru Sangama 4 3 AHFF 81 FAF 91 29-06-1991 45 19.55 48 30 Bagekarangi Bidar BIDAR Bidar Bidar BAGEKARANJI 5 5 FEE 91 FAF 2006 23-12-2006 Bidar BIDAR Aurad Kasaba Senballi 87 9.75 24.00 9.00 Senballi 6 6 FEE 87 FAF 2006 28-11-2006 Bidar BIDAR Aurad KUSHANURU BALATH - K 37 23 56 83 BALATH - K 7 7 FEE 81 FAF 2006 23-12-2006 Bidar BIDAR Aurad Dabaka Dungaragav 79 12.00 Dungaragav FEE 81 FAF 2006 23-12-2006 Bidar BIDAR Aurad Dabaka Dungaragav 82 15.50 Dungaragav 4 AHFF 128 FAF 91 16-09-1995 93 15 37 65 Basanthapura Bidar BIDAR Bidar Bidar BASANTHAPURA AHFF 128 FAF 91 16-09-1995 24 21 51 89 Basanthapura Bidar BIDAR Bidar Bidar BASANTHAPURA 8 5 AHFF 78 FAF 91 17-06-1991 220 27.6 68 19 Bidar ORAD CHIKALI-JANAVADA BIDAR 9 6 AHFF 146 FAF 91 30-05-1991 27 -

Notification of Containment Zone District Bidar

NOTIFICATION OF CONTAINMENT ZONE DISTRICT BIDAR In view of power delegated to Chairperson, Bidar, District Disaster Management Authority under National Disaster Management wtd NDMA, Act (NDMA) ZOdS Uy C.O. No. RD 157 iNR 2020 and in exercise ofthe powers conferred under section 26,30 34 of 2oo5' and Under relevant paras ofnotification issued under Epidemic Disease Ac! 1897 by State Government, and AsperdefinitionofContainmentZonevideG.O.No.HFWlogACS2020datsd:17-04-2020. I hereby declare sunounding 100 mtrs area as an Active Containment Zone for Z 。 n Zone Name Patients Confirmed Incident Population Shops Houses e Number Date Commander N 。 。 653 KAヽ4AL NAGAR P-142013 02-08-2020 Tahsildar 60 2 12 Kamalnagar 301 TORNA P-142014,P-142085 02-08-2020 Tahsildar 45 4 18 Kamalnagar つ 55 ん 14 677 AURAD TOWN P-142683 02-08-2020 Tahsildar Aurad (B) 44 4 18 698 MURKI P-145841 03¨ 08-2020 Tahsildar Kamalnagar 2 19 352 VIDYA NAGAR COLONY BIDAR P-142088 02-08-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 55 22 594 NOUBAD BIDAR P-142569 02-08-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 77 1 389 J.P.NAGAR BIDAR P-142848 02-08-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 84 4 15 2 17 450 GADGI VILLAGE P-143830 02-08-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 66 778 HOLI CROSS SANTHPUR P-142701 02-08-2020 Tahsildar Allrad(B) 50 1 15 49 4 22 179 SHAH GUNJBIDAR P-142709 02-08…2020 Tahsildar Bidar 88 2 19 780 LIG 14 KI‐ IB BIDAR P… 142715 02-08-2020 Tahsildar Bidar 781 HALADKERIBIDAR P-t42884,P-143639 02-08-2020 Tahs ldar Bidar 97 4 33 2 19 782 AGRICULTURE COLONY P-144109 02-08… 2020 Tahs ldar Bidar 55 う D 83 4 02-08-2020 I IahSildar Bidar l 783 66 1