The Music of Maurice Ohana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ITALIAN, PORTUGUESE, SPANISH and LATIN AMERICAN SYMPHONIES from the 19Th Century to the Present

ITALIAN, PORTUGUESE, SPANISH AND LATIN AMERICAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century to the Present A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman FRANCO ALFANO (1876-1960, ITALY) Born in Posillipo, Naples. After studying the piano privately with Alessandro Longo, and harmony and composition with Camillo de Nardis and Paolo Serrao at the Conservatorio di San Pietro a Majella, Naples, he attended the Leipzig Conservatory where he completed his composition studies with Salomon Jadassohn. He worked all over Europe as a touring pianist before returning to Italy where he eventually settled in San Remo. He held several academic positions: first as a teacher of composition and then director at the Liceo Musicale, Bologna, then as director of the Liceo Musicale (later Conservatory) of Turin and professor of operatic studies at the Conservatorio di San Cecilia, Rome. As a composer, he speacialized in opera but also produced ballets, orchestral, chamber, instrumental and vocal works. He is best known for having completed Puccini’s "Turandot." Symphony No. 1 in E major "Classica" (1908-10) Israel Yinon/Brandenburg State Orchestra, Frankfurt ( + Symphony No. 2) CPO 777080 (2005) Symphony No. 2 in C major (1931-2) Israel Yinon/Brandenburg State Orchestra, Frankfurt ( + Symphony No. 1) CPO 777080 (2005) ANTONIÓ VICTORINO D'ALMEIDA (b.1940, PORTUGAL) Born in Lisbon.. He was a student of Campos Coelho and graduated from the Superior Piano Course of the National Conservatory of Lisbon. He then studied composition with Karl Schiske at the Vienna Academy of Music. He had a successful international career as a concert pianist and has composed prolifically in various genres including: instrumental piano solos, chamber music, symphonic pieces and choral-symphonic music, songs, opera, cinematic and theater scores. -

TMS 3-1 Pages Couleurs

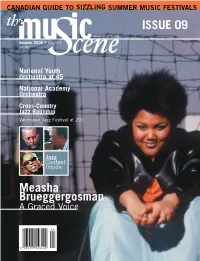

TMS3-4cover.5 2005-06-07 11:10 Page 1 CANADIAN GUIDE TO SIZZLING SUMMER MUSIC FESTIVALS ISSUE 09 www.scena.org Summer 2005 • Vol. 3.4 $4.95 National Youth Orchestra at 45 National Academy Orchestra Cross-Country Jazz Roundup Vancouver Jazz Festival at 20! Jazz Contest Inside Measha Brueggergosman A Graced Voice 0 4 0 0 6 5 3 8 5 0 4 6 4 4 9 TMS3-4 glossy 2005-06-06 09:14 Page 2 QUEEN ELISABETH COMPETITION 5 00 2 N I L O I V S. KHACHATRYAN with G. VARGA and the Belgian National Orchestra © Bruno Vessié 1st Prize Sergey KHACHATRYAN 2nd Prize Yossif IVANOV 3rd Prize Sophia JAFFÉ 4th Prize Saeka MATSUYAMA 5th Prize Mikhail OVRUTSKY 6th Prize Hyuk Joo KWUN Non-ranked laureates Alena BAEVA Andreas JANKE Keisuke OKAZAKI Antal SZALAI Kyoko YONEMOTO Dan ZHU Grand Prize of the Queen Elisabeth International Competition for Composers 2004: Javier TORRES MALDONADO Finalists Composition 2004: Kee-Yong CHONG, Paolo MARCHETTINI, Alexander MUNO & Myung-hoon PAK Laureate of the Queen Elisabeth Competition for Belgian Composers 2004: Hans SLUIJS WWW.QEIMC.BE QUEEN ELISABETH INTERNATIONAL MUSIC COMPETITION OF BELGIUM INFO: RUE AUX LAINES 20, B-1000 BRUSSELS (BELGIUM) TEL : +32 2 213 40 50 - FAX : +32 2 514 32 97 - [email protected] SRI_MusicScene 2005-06-06 10:20 Page 3 NEW RELEASES from the WORLD’S BEST LABELS Mahler Symphony No.9, Bach Cantatas for the feast San Francisco Symphony of St. John the Baptist Mendelssohn String Quartets, Orchestra, the Eroica Quartet Michael Tilson Thomas une 2005 marks the beginning of ATMA’s conducting. -

TEMPO Henri Dutilleux and Maurice Ohana

TEMPO http://journals.cambridge.org/TEM Additional services for TEMPO: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Henri Dutilleux and Maurice Ohana: Victims of an Exclusion Zone?. Caroline Rae TEMPO / Volume 212 / Issue 212 / April 2000, pp 22 - 30 DOI: 10.1017/S0040298200007580, Published online: 23 November 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0040298200007580 How to cite this article: Caroline Rae (2000). Henri Dutilleux and Maurice Ohana: Victims of an Exclusion Zone?. TEMPO, 212, pp 22-30 doi:10.1017/S0040298200007580 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TEM, IP address: 131.251.254.238 on 31 Jul 2014 Caroline Rae Henri Dutilleux and Maurice Ohana: Victims of an Exclusion Zone? Until recently, the music of Henri Dutilleux and known more as a concert pianist than as a com- Maurice Ohana was largely overlooked in poser and by 1939 had given recitals at the Salles Britain, despite both composers having achieved Gaveau and Chopin, performed concertos with widespread recognition beyond our shores. In the orchestras of the Concerts Lamoureux and France they have ranked among the leading Pasdeloup, and completed several European composers of their generation since at least the tours. (In 1947 he gave recitals in London at the 1960s and have received many of the highest Wigmore Hall as well as for the BBC Home official accolades. In Britain, the view of French Service.) Indicating the path of his subsequent music since 1945 has often been synonymous compositional development, his recital program- with the music of Olivier Messiaen and Pierre mes reflected a cultural alignment independent Boulez, to the virtual exclusion of others whose of the Austro-German tradition and typically work has long been honoured not only in comprised works by Scarlatti, Chopin, Debussy, France and elsewhere in Europe but in the Ravel and the Spaniards, Falla, Albeniz and wider international arena. -

Gaëlle Solal

Canterbury Guitar Society Chairperson: Miles Roberts, Secretary/Treasurer: John Kemp, 61, Chipstead Lane, Chipstead, Sevenoaks, Kent TN13 2AJ 55, South St., Whitstable, Kent CT5 3EA Tel: 01732 453523 Email: [email protected] Tel: 01227 265503 Email: [email protected] Gaëlle Solal FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE, CANTERBURY Monday 16th June 2014 7.30pm Gaëlle Solal Born in Marseilles (France) in 1978, Gaëlle began the study of the guitar at age of 6 with René Bartoli. At 14, she won three gold medals at the Conservatoire de Marseilles and, as the best student of all instruments, was awarded the Prix de la Ville de Marseille. She has studied with Alberto Ponce at Conservatoire Supérieur de Musique de Paris, Roberto Aussel at Musikhochscule Köln and Alvaro Pierri at Université du Québec à Montréal. She has enjoyed participating in master classes with legendary guitarists including Antigoni Goni, Pepe Romero, Roland Dyens, Oscar Ghiglia, Leo Brouwer, Alvaro Pierri and Joaquin Clerch. Her list of prizes ot international competitions includes: 1st Grand Prix at Alessandria Competition, 1st Prize in Locquémeau, 1st Prize in Savona, 1st Prize in Sernancehle, Finalist at Concert Artists Guild New York, Honor Diplom at Accademia Chigiana and 2nd Prize at Guitar Foundation of America. She has performed in the Festival d'Ile de France, Noches en los Reales Alcázares in Sevilla, Festival dAvignon, Festival Montpellier- Radio France and at Salle Cortot (Paris), Zellerbach Hall (Berkeley), Tsuda Hall, Nikkei Hall, Oji Hall in Tokyo, Merkin Concert Hall (NY), and the Guitar Foundation of American Convention in Columbus (GA). She recorded for NHK, France Musiques, RFI, and RAI. -

Julian Bream's 20Th Century Guitar: an Album's Influence on the Modern Guitar Repertoire

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Julian Bream's 20th Century Guitar: An Album's Influence on the Modern Guitar Repertoire Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5rg2n57t Author Greene, Taylor Jonathon Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Julian Bream’s 20th Century Guitar: An Album’s Influence on the Modern Guitar Repertoire A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the degree requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music by Taylor Jonathon Greene June 2011 Thesis Committee: Dr. Walter A. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Byron Adams Dr. Rogério Budasz Copyright by Taylor Jonathon Greene 2011 The Thesis of Taylor Jonathon Greene is approved: ______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Table of Contents I. Introduction 1 II. Julian Bream A. Julian, the Young Guitar Prodigy 4 B. Breaking Away 8 C. Pivotal Events in Bream’s Early Career 14 III. The Guitar in the Twentieth Century A. The Segovian Tradition: Nationalism and Conservatism 18 B. Other Guitarists 28 IV. Julian Bream and the Creation of a New Guitar Repertoire A. Departures from Segoivan Repertoire 31 B. Origins of Bream’s Choices in Repertoire 32 C. Bream’s Recordings and the Guitar Repertoire 35 V. The Album and the 1960s A. The Album Cover 42 B. Psychedelia and 20th Century Guitar 45 VI. Reginald Smith Brindle’s El Polifemo de Oro A. Smith Brindle and Serialism on the Guitar 48 B. El Polifemo de Oro: Soft Serialism 55 VII. -

Catalogue Auteur De Maurice Ohana

MAURICE OHANA n e i v i V y u G : o t o h P Gérard Billaudot Éditeur MAI 2003 Maurice OHANA Catalogue des œuvres Catalogue of works Werkverzeichnis Catalogo de obras Gérard Billaudot Éditeur 14 rue de l’Echiquier - 75010 PARIS - FRANCE Tél. : (33) 01.47.70.14.46 - Télécopie : (33) 01.45.23.22.54 E-mail : [email protected] - www.billaudot.com MAURICE OHANA (1913-1992) Né le 12 juin 1913 à Casablanca, Maurice Ohana a fait presque toutes ses études musicales en France, tout en poursuivant ses études classiques. Il s’orienta quelques temps vers l’architecture qu’il abandonna pour se consacrer entièrement à la musique. Très jeune, il débute comme pianiste au Pays Basque où sa famille est fixée ; sa car - rière reste prometteuse jusqu’à la guerre qui va l’entraîner loin du monde musical mais aussi l’y ramener, à Rome, où il est l’élève et ami d’Alfredo Casella à l’Académie Sainte-Cécile. Sitôt démobilisé, il se fixe à nouveau à Paris en 1946. C’est à cette époque que ses pre mières œuvres sont connues en France. Il fonde, avec trois amis, le «Groupe Zodiaque», qui se propose de défendre la liberté d’expression contre les esthétiques dictatoriales alors en vogue. Et jusqu’à ce jour, il continue à faire sien le manifeste de ces combats de jeunesse. Des constantes profondes apparaissent dans son œuvre. Du Llanto por Ignacio Sanchez Mejias (1950) aux œuvres récentes, l’évolution tend vers une rigueur curieusement associée à une grande liberté d’allure, tant dans l’écriture que dans les rapports avec l’interprète. -

The Piano Music of Maurice Ohana

The Piano Music of Maurice Ohana by Caroline Rae A composer whose first works date from his early thirties and whose first important, large-scale composition does not appear until the age of thirty-seven could well be perceived as a late starter. This to some extent was the case with Maurice Ohana. The earliest works which he allowed to remain in his catalogue were composed towards the end of the Second World War when, taking advantage of his army posting to Italy, he enrolled in the piano class of Alfredo Casella at the Academia Santa Cecilia in Rome. I Ohana's first large-scale work, the setting of Federico Garcia Lorca's Llanto par Ignacio Sanchez Mejias for baritone, narrator chorus and orchestra, followed some years later being completed, and receiving its first performance, in 1950. Although he established his compositional presence later than most others belonging to that illustrious generation of composers born in and around 1913, it would be misleading to suggest that Ohana either came to music late in life or was to any extent a late developer.' His real beginnings as a composer were delayed not only by the Second World War, but by the success of his first career as a concert pianist which he pursued throughout the 1930s and for some time after his war service. It is not surprising, therefore, that music for his own instrument, the piano, should figure prominently in Ohanas catalogue. Indeed, much of his compositional development is reflected through his work in this medium, his music for solo piano spanning almost all of his creative years from the mid 1940s to the mid 1980s. -

The History of the Guitar

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Music Faculty Research Music Fall 12-2015 The iH story of the Guitar Júlio Ribeiro Alves Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/music_faculty Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Alves, Júlio Ribeiro. The iH story of the Guitar: Its Origins and Evolution. Huntington, 2015. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The History of the Guitar: Its Origins and Evolution A Handbook for the Guitar Literature Course at Marshall University Júlio Ribeiro Alves To Eustáquio Grilo, Inspiring teacher and musician 1 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: The Origins 6 Chapter 2: The Guitar in the Renaissance 14 The Vihuela 15 The Four-Course Guitar 31 The Lute 40 Chapter 3: The Guitar in the Baroque 43 Chapter 4: The Guitar in the Classic and Romantic Periods 68 Towards the Six-String Guitar 68 Guitar Personalities of the Nineteenth Century 76 Chapter 5: The Transition to the Twentieth Century 102 Chapter 6: The Guitar in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century In the Twenty-First Century 138 Notable Performers 139 The Guitar as an Ensemble Instrument 149 Guitar Composers of the Twentieth and Twenty First Centuries 154 New Improvements in Guitar Strings and Construction 161 Conclusion 163 Bibliography 165 2 Introduction “Las Mujeres y Cuerdas Las mujeres y cuerdas De la guitarra, Es menester talento Para templarlas.