The York Street Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woolloomooloo-Brochure-170719.Pdf

Your companion on the road. We make your life stress-free by providing everything you need to create the stay you want. Apartment living with the benefits of a hotel service. stay real. Sydney’s harbour side suburb. Nesuto Woolloomooloo is situated on the Sydney city centre fringe, in the beautiful harbour side suburb of Woolloomooloo, about 900 metres from the heart of Sydney city on the eastern side towards Potts Point. These fabulous serviced-apartments are set in a beautiful heritage listed 4 storey building, located amongst traditional Sydney terrace houses in the tree lined streets of historic Woolloomooloo, a 3-minute walk from the restaurants and bars at Finger Wharf and the legendary Harry’s Cafe de Wheels. Nesuto Woolloomooloo Sydney Apartment Hotel offers a range of self-contained Studio, One, Two and Three Bedroom Apartments, allowing you to enjoy all the comforts of home whilst providing the convenience of apartment style accommodation, making it ideal for corporate and leisure travellers looking for short term or long stay accommodation within Sydney. Nesuto. stay real. A WELCOMING LIVING SPACE Nesuto Woolloomooloo Sydney Apartment Hotel offers a range of spacious self-contained Studio, One, Two and Three Bedroom Apartments in varying styles and layouts. We offer fully equipped kitchenettes, varied bedding arrangements and spacious living areas, ideal for guests wanting more space, solo travellers, couples, families, corporate workers or larger groups looking for a home away from home experience. Our Two and Three Bedroom apartments, along with some Studio apartments, have full length balconies offering spectacular views of the Sydney CBD cityscape and Sydney Harbour Bridge. -

PORTRAITURE and the PRIZE ART an Education Kit for K–6 Creative Arts with KLA Links GALLERY and 7–12 Visual Arts NSW

PORTRAITURE AND THE PRIZE ART An education kit for K–6 Creative Arts with KLA links GALLERY and 7–12 Visual Arts NSW ARCHIBALD.PRIZE.2010 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Toured by Museums & Galleries New South Wales www.thearchibaldprize.com.au PORTRAITURE AND THE PRIZE Contents General: the Archibald Prize and portraiture Who was JF Archibald? The Archibald Prize 1 A chronology of events Controversy and debate Portraiture as a genre: an overview Portraiture and the Prize: a selection of quotes List of winners since 1921 Syllabus connections: the Archibald Prize and portraiture Suggested case studies Years 7–12 Conceptual framework: the art world web Years 7–12 Framing the Archibald: questions for discussion Years 7–12 2 Portraiture: general strategies Years K–6 Vocabulary: portraiture Artists: portraiture References Syllabus connections: 2010 Archibald Prize Framing the Archibald: K–6 and 7–12 discussion questions and activities Analysing the winner K–6: Visual Arts and links with key learning areas 3 Years 7–12: The frames Focus works: K–6: Visual Arts and links with key learning areas 7–12: Issues for discussion 2010 Archibald Prize: selected artists Education kit outline This education kit has been prepared by the Public Programs Department of the Art Gallery of New South Wales in conjunction with Museums & Galleries New South Wales, to accompany the annual Archibald Prize exhibition. It has been designed to assist primary and secondary students and teachers in their enjoyment and understanding of the Archibald exhibition and the issues surrounding it, at the Art Gallery of NSW or throughout the 2010 Archibald Prize Regional Tour. -

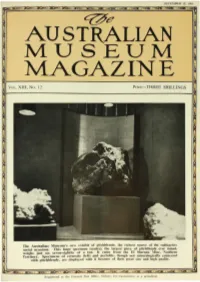

Andamooka Opal Field- 0

DECEMBER IS, 1961 C@8 AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM MAGAZINE VoL. XliL No. 12 Price-THREE SHILLINGS The Austra lian Museum's new exhibit of pitchblende, the richest source of the radioactive metal uranium. T his huge specimen (centre), the largest piece of pitchblende ever mined, weighs just on seven-eighths ?f a ton. 1t came. from the El S l~ eran a ~, line , Northern Territory. Specimens of ccruss1te (left) and pectohte. thOUf!h not nuneralog•cally connected with pitchblende, arc displayed with it because of their great size and high quality. Re gistered at the General Post Office, Sydney, for transmission as a peri odical. THE AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM HYDE PARK, SYDNEY BO ARD O F TRUSTEES PRESIDENT: F. B. SPENCER CROWN TRUSTEE: F. B. SPENCER OFFICIAL TRUSTEES: THE HON. THE CHIEF JUSTICE. THE HON. THE PRESIDENT OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL. THE HON. THE CHIEF SECRETARY. THE HON. THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL. THE HON. THE TREASURER. THE HON. THE MINISTER FOR PUBLIC WORKS. THE HON. THE MINISTER FOR EDUCATION. THE AUDITOR-GENERAL. THE PRESIDENT OF THE NEW SOUTH WALES MEDICAL BOARD. THE SURVEYOR-GENERAL AND CHIEF SURVEYOR. THE CROWN SOLICITOR. ELECTIVE TRUSTEES: 0. G. VICKER Y, B.E., M.I.E. (Aust.). FRANK W. HILL. PROF. A. P. ELKIN, M.A., Ph.D. G. A. JOHNSO N. F. McDOWELL. PROF. J . R. A. McMILLAN, M.S., D .Sc.Agr. R. J. NOBLE, C.B.E., B.Sc.Agr., M.Sc., Ph.D. E. A. 1. HYDE. 1!. J. KENNY. M.Aust.l.M.M. PROF. R. L. CROCKER, D.Sc. F. L. S. -

The AWA Microphone for Harbour Bridge 75Th

..The Microphone used for the Sydney Harbour Bridge Opening ceremony. Compiled by David Burger, March 2007 with material from: - Phil Burgess Telstra, - Ted Miles – ex AWA technician. Press Release No. 94 (14/03/07) – Telstra's Sydney Harbour Bridge 75th birthday gift Phil Burgess, GMD, Public Policy and Communication, Telstra. Telstra has donated a rare microphone from its historical collection used to open the Sydney Harbour Bridge 75 years ago to the Sydney Powerhouse Museum - and it has created a bit of excitement. The Reisz microphone is a rare example of Australian technology manufactured in 1930 and was used to broadcast the 1932 opening ceremony of the Sydney Harbour Bridge to thousands of people. What has made the microphone especially significant is the signatures of all 10 dignitaries at the opening ceremony, including the NSW Premier John T Lang, NSW Governor Philip Game and the Bridge's Chief Engineer, JJC Bradfield. Speaking at the official donation event, Telstra's Group Managing Director PP&C Phil Burgess said that Telstra was proud to share this wonderful piece of Australian history with the community on the 75th birthday of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. "Every good piece of history has a story behind it and this microphone is no exception," Dr Burgess said. "Thanks to the Powerhouse Museum, many more people will be able to see and understand the role it played in unveiling a great Aussie icon." Why did Telstra have the microphone in its historical collection? The microphone became one of a collection of microphones owned by Mr Philip Geeves who was announcing for AWA (Amalgamated Wireless Australia Ltd) on the day of the Sydney Harbour Bridge opening. -

Built Pedagogy

Above any other faculty, the very fabric of the New Building Built for the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning must Pedagogy function as an experiential resource for research, teaching and knowledge transfer. This presents a rare opportunity for profound, intrinsic and meaningful links between building programme and architectural expression Cultural resources can engage communities in collective experiences, providing opportunities for reflection and conversation on the never-ending questions of how we make our lives meaningful, our work valuable and our values workable. 05.1.1 Growing Esteem, 2005 The Gallery Building reinforces the horizontal lines in the landscape and respects, engages with and reinforces the character of the Collections and Research Building Urban Design Exemplar Precinct established by the High Court and the National Gallery of Australia; Australian Museum, Sydney Integration with Environment Seeking to learn about sustainable build- ing through study of the natural world, Enduring, High Quality, Timeless the double skin façade is a collaboration Distinctive Materials and Detailing with the Museums scientists - a visible, intrinsic and poetic link between architec- National Portrait Gallery tural expression and the institution’s iden- Canberra, Australia tity. Nature’s golden ratio and the filigree of a moth’s wing scale, seen through a Won in open international scanning electron microscope, inspire the competition and completed in glazing pattern. Innovative inventive use 2008, the National Portrait Gallery of dichroic glass and advanced concealed is the most significant new national edgelighting produces dynamic colours institution in the Parliamentary through optical interference as do irides- Triangle for almost 20 years. cent butterflies. Canberra - City and Environs, Griffin Legacy Framework Plan, NCA, 2004. -

Sydney Harbour Bridge Other Names: the Coat Hanger Place ID: 105888 File No: 1/12/036/0065

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Historic Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: Sydney Harbour Bridge Other Names: The Coat Hanger Place ID: 105888 File No: 1/12/036/0065 Nomination Date: 30/01/2007 Principal Group: Road Transport Status Legal Status: 30/01/2007 - Nominated place Admin Status: 19/09/2005 - Under assessment by AHC--Australian place Assessment Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: National Trust of Australia (NSW) : Classified by National Trust Location Nearest Town: Dawes Point - Milsons Point Distance from town (km): Direction from town: Area (ha): 9 Address: Bradfield Hwy, Dawes Point - Milsons Point, NSW 2000 LGA: Sydney City NSW North Sydney City NSW Location/Boundaries: Bradfield Highway, Dawes Point in the south and Milsons Point in the north, comprising bridge, including pylons, part of the constructed approaches and parts of Bradfield and Dawes Point Parks, being the area entered in the NSW Heritage Register, listing number 00781, gazetted 25 June 1999, except those parts of this area north of the southern alignment of Fitzroy Street, Milsons Point or south of the northern alignment of Parbury Lane, Dawes Point. Assessor's Summary of Significance: The building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge was a major event in Australia's history, representing a pivotal step in the development of modern Sydney and one of Australia’s most important cities. The bridge is significant as a symbol of the aspirations of the nation, a focus for the optimistic forecast of a better future following the Great Depression. With the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Australia was felt to have truly joined the modern age, and the bridge was significant in fostering a sense of collective national pride in the achievement. -

Attachment A

Attachment A Report Prepared by External Planning Consultant 3 Recommendation It is resolved that consent be granted to Development Application D/2017/1652, subject to the following: (A) the variation sought to Clause 6.19 Overshadowing of certain public places in accordance with Clause 4.6 'Exceptions to development standards' of the Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 be supported in this instance; and (B) the requirement under Clause 6.21 of the Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 requiring a competitive design process be waived in this instance; and (C) the requirement under Clause 7.20 of the Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 requiring the preparation of a development control plan be waived in this instance; Reasons for Recommendation The reasons for the recommendation are as follows: (A) The proposal, subject to recommended conditions, is consistent with the objectives of the planning controls for the site and is compatible with the character of the area into which it will be inserted. It will provide a new unique element in the public domain which has been specifically designed to highlight Sydney’s main boulevard and the important civic precinct of Town Hall and the Queen Victoria Building. (B) The proposed artwork is permissible on the subject land and complies with all relevant planning controls with the exception of overshadowing of Sydney Town Hall steps. While the proposal will result in some additional shadowing of the steps this impact will be minor and is outweighed by the positive impacts of the proposal. (C) The proposal is of a nature compatible with the overall function of the locality as a civic precinct in the heart of the Sydney CBD. -

Conservation Management Plan

3.4. HISTORICAL TIMELINE The following tables contains a chronology of significant events in the history of the site and the subject building as summarised from Sections 3.2 and 3.3 and building/development application information drawn from the City of Sydney Planning Cards. The development of the site can generally be separated into four phases of development, as follows: 1. New Belmore Market 1893 - 1913 2. Wirths Hippodrome 1914 – 1926 3. Capitol Theatre 1927 – 1991 4. Restored Capitol Theatre 1992 – Present Table 4 – Historical Timeline Date Event 1866 Construction of Belmore Markets begins on a site bounded by Castlereagh, Hay, Pitt and Campbell. 1869 Belmore Markets opens on 14 May. Phase 1: New Belmore Markets 1893 Second Belmore Markets (Capitol site) open. Used for theatrical and circus performances on Saturday nights. 1910 Council decides that the Tivoli and Capitol (two theatres) would be erected on the sites of the old and new Belmore Markets. 1912 Wirth Bros takes a 10-week lease on the new Belmore Theatre for a ‘circus and hippodrome’. The council claimed the auditorium could be used as hippodrome, circus, theatre, opera house, concert hall, vaudeville entertainment hall or for photo plays (early silent motion pictures). Phase 2: Wirths Hippodrome 1914-1915 Belmore Markets dismantled and re-erected as the Hippodrome – home of Wirths Circus in Australia. The detail of the market walls was erected 10 metres higher. 1916 On April 3, Wirths Circus and Hippodrome opens – the largest theatre in Australia. The 13-metre ring in front of the proscenium arch had a hydraulically operated floor which dropped to fill with water for aquatic events. -

Annual Report 2016-17 Delivering Sustainable and World-Leading Public Parklands About Centennial Centennial Parklands 5 the Hon

Centennial Parklands Annual Report 2016-17 Delivering sustainable and world-leading public parklands About Centennial Centennial Parklands 5 The Hon. Gabrielle Upton MP Acknowledgement of Parklands Chairman’s report 6 Traditional Owners 04 Executive Director’s report 7 The Hon. Gabrielle Upton MP We acknowledge the Gadigal clan as the Highlights for 2016-2017 8-9 Minister for Environment, traditional custodians of the country on which Botanic Gardens & Minister for Local Government Centennial Parklands has been constructed. and Minister for Heritage Centennial Parklands Strategic Plan 10 52 Martin Place SYDNEY NSW 2000 Statement of Record 24 October 2017 Managing Resources for Sustainability 13 This Annual Report for 2016-17 complies with the Environmental Annual Reporting requirements for NSW Government, Performance Managing our Environment 14 Dear Minister, and contains the Centennial Park and Moore Park 12 Planning and development issues 15 Trust’s performance against the strategies of the In accordance with the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Centennial Parklands Plan of Management 2015-20. Sustainable Parklands Program 15 Act 1984, the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983 and the Regulations under those Acts, we have pleasure in submitting the Annual Report for 2016-17 of the Centennial Park and Moore Park Trust. Social Visitation 17 16 Performance Sports in the Parklands 18 Education and community programs 19 Volunteering 19 Venue management 20 Tony Ryan Adam Boyton Community Consultative Committee 21 Chairman Trustee Financial Fees and charges 23 22 Performance Economic performance 24 Payment performance 24 Accounts payable 24 Investment performance 25 Financial Statement by Members of the Trust 27 26 Statements Independent Audit Report 28 Statement of Comprehensive Income 30 Statement of Financial Position 31 Statement of Changes in Equity 32 Statement of Cash Flows 33 Appendices Governance and organisational matters 59 58 The Trustees 60 Risk management 62 Organisational Matters 65 The Executive team 66 Did you know.. -

Changing Stations

1 CHANGING STATIONS FULL INDEX 100 Top Tunes 190 2GZ Junior Country Service Club 128 1029 Hot Tomato 170, 432 2HD 30, 81, 120–1, 162, 178, 182, 190, 192, 106.9 Hill FM 92, 428 247, 258, 295, 352, 364, 370, 378, 423 2HD Radio Players 213 2AD 163, 259, 425, 568 2KM 251, 323, 426, 431 2AY 127, 205, 423 2KO 30, 81, 90, 120, 132, 176, 227, 255, 264, 2BE 9, 169, 423 266, 342, 366, 424 2BH 92, 146, 177, 201, 425 2KY 18, 37, 54, 133, 135, 140, 154, 168, 189, 2BL 6, 203, 323, 345, 385 198–9, 216, 221, 224, 232, 238, 247, 250–1, 2BS 6, 302–3, 364, 426 267, 274, 291, 295, 297–8, 302, 311, 316, 345, 2CA 25, 29, 60, 87, 89, 129, 146, 197, 245, 277, 354–7, 359–65, 370, 378, 385, 390, 399, 401– 295, 358, 370, 377, 424 2, 406, 412, 423 2CA Night Owls’ Club 2KY Swing Club 250 2CBA FM 197, 198 2LM 257, 423 2CC 74, 87, 98, 197, 205, 237, 403, 427 2LT 302, 427 2CH 16, 19, 21, 24, 29, 59, 110, 122, 124, 130, 2MBS-FM 75 136, 141, 144, 150, 156–7, 163, 168, 176–7, 2MG 268, 317, 403, 426 182, 184–7, 189, 192, 195–8, 200, 236, 238, 2MO 259, 318, 424 247, 253, 260, 263–4, 270, 274, 277, 286, 288, 2MW 121, 239, 426 319, 327, 358, 389, 411, 424 2NM 170, 426 2CHY 96 2NZ 68, 425 2Day-FM 84, 85, 89, 94, 113, 193, 240–1, 243– 2NZ Dramatic Club 217 4, 278, 281, 403, 412–13, 428, 433–6 2OO 74, 428 2DU 136, 179, 403, 425 2PK 403, 426 2FC 291–2, 355, 385 2QN 76–7, 256, 425 2GB 9–10, 14, 18, 29, 30–2, 49–50, 55–7, 59, 2RE 259, 427 61, 68–9, 84, 87, 95, 102–3, 107–8, 110–12, 2RG 142, 158, 262, 425 114–15, 120–2, 124–7, 129, 133, 136, 139–41, 2SM 54, 79, 84–5, 103, 119, 124, -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

Scientists' Houses in Canberra 1950–1970

EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 MILTON CAMERON Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cameron, Milton. Title: Experiments in modern living : scientists’ houses in Canberra, 1950 - 1970 / Milton Cameron. ISBN: 9781921862694 (pbk.) 9781921862700 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Scientists--Homes and haunts--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Architecture, Modern Architecture--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Canberra (A.C.T.)--Buildings, structures, etc Dewey Number: 720.99471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Sarah Evans. Front cover photograph of Fenner House by Ben Wrigley, 2012. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press; revised August 2012 Contents Acknowledgments . vii Illustrations . xi Abbreviations . xv Introduction: Domestic Voyeurism . 1 1. Age of the Masters: Establishing a scientific and intellectual community in Canberra, 1946–1968 . 7 2 . Paradigm Shift: Boyd and the Fenner House . 43 3 . Promoting the New Paradigm: Seidler and the Zwar House . 77 4 . Form Follows Formula: Grounds, Boyd and the Philip House . 101 5 . Where Science Meets Art: Bischoff and the Gascoigne House . 131 6 . The Origins of Form: Grounds, Bischoff and the Frankel House . 161 Afterword: Before and After Science .