Please Do Not Quote Or Circulate Without the Author's Permission. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adaptation and Training of Rural Workers for Industrial Work

DOCO4FNT RPSIIMF ED 023 820 VT 005 030 By -Barbichon, Guy Adaptation and Traming of Rural Workers for Industrial Work, Co -ordination of Research. Orgarwsation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris (France). Pub Date Dec 62 Note-142p. Available from-OECD Publication Center, Suite1305, 1750 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, DC. 20006 ($1 25). EDRS Price MF -SO 75 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors -Adjustment (to Environment), *Agricultural Laborers, Bibliographies, Change Agents, Conferences, Economic Development, Industrialization, Industry, 'Migration Patterns, *Mobility, Occupational Research Methodology, Research Proposals, *Research Reviews (Publications), *Vocational Adlustment Identifiers -France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden The conference organized by the European Productivity Agency in Se_ptember 1960 and subsecuentmeetingsarranged bytheOrganizationforEconomic Cooperation and Development gave the representatives of workers, employers, administrators, and research workers of many European countries the opportunity to exchange information on the knowledge accluired and the studies underway on the movement of rural workers to industry. Mobility of agricultural manpower isan important facet of the problem of general mobility of the total active population inthe course of economic development.On the one hand, mobility is desirable in order to reduce the degree of under-employment in agriculture and, on the other hand, the growth of non-agricultural enterprise needs to draw upon the agricultural population for a supply of labor. To improve economic conditions the concurrent development of both the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors of the economy and agricultural policy must be closely integrated with general economic policy. The appendixes include national bibliographical references and summaries of national research on the problems of adaptation and training of rural workers in Germany, France, Italy, Norway, The Netherlands, and Sweden, and prolect proposals for international research on the topic. -

Frederiksgave Plantation and Common Heritage Site

Frederiksgave Plantation and Common Heritage Site A historical exhibition and cultural centre covering a chapter in the history of Ghana’s and Denmark’s common past and cultural heritage For information or booking guided tours at Frederiksgave Plantation and Common Heritage Site: Frederiksgave Plantation http://www.natmus.dk/ghana and Common Heritage Site Dr. Yaw Bredwa-Mensah Mobile: (+233) (0) 244141440 Email: [email protected] Representatives in the village of Sesemi Sasu, phone: (+233) (0) 243187270 Addo, phone: (+233) (0) 277010788 Ecological Laboratories (ECOLAB) Prof. Seth K.A.Danso, Director P.O. Box LG 59 Legon- Accra, Ghana Tel: (+233) (21) 512533 / 500394 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] National Museum of Denmark Frederiksholms Kanal 12 1220 Copenhagen K Denmark Tel: (+45) 33473204 / (+45) 33473901 Email: [email protected] A historical exhibition and cultural centre covering a chapter in the history of Ghana’s and Denmark’s common past and cultural heritage Frederiksgave Plantation and Common Heritage Site The exhibitions at Frederiksgave are the results of co-operation between researchers and architects from Ghana and Denmark This booklet, as well as the texts for the exhibitions, was written by Dr. Yaw Bredwa-Mensah, University of Ghana, Ole Justesen, University of Copenhagen, and Anne Mette Jørgensen, the National Museum of Denmark. Translation from the Danish by Peter I. Crawford. Graphic for this booklet and the exhibitions were produced by Nan Tøgern, Copenhagen. Exhibition posters: Penta Serigrafi, Roskilde, Denmark. Printing of booklet: Kailow Tryk, Rødovre, Denmark. Other work on the exhibitions was made by Benjamin Ohene Djan, Bossman Murey, Frederick Amekudi, Nana Nimo II, Nikolaj Hyllestad, Marianne Blank, Maruiska Solow, Anna Seeberg Braun and Nathalia Brichet. -

Old New Unknown

Charlotta Forss Charlotta Forss The Old, the New and the Unknown This thesis investigates early modern ways of looking at the world through an analysis of what the continents meant in three settings of knowledge making in seventeenth-century Sweden. Combining text, maps and images, the thesis anal- yses the meaning of the continents in, frst, early modern scholarly ‘geography’, second, accounts of journeys to the Ottoman Empire and, third, accounts of journeys to the colony New Sweden. The investigation explores how an under- standing of conceptual categories such as the continents was intertwined with processes of making and presenting knowledge. In this, the study combines ap- proaches from conceptual history with research on knowledge construction and circulation in the early modern world. The thesis shows how geographical frameworks shifted between settings. There was variation in what the continents meant and what roles they could fll. Rather THE than attribute this fexibility to random variation or mistakes, this thesis inter- The Old, the New and Unknown OLD prets fexibility as an integral part of how the world was conceptualized. Reli- gious themes, ideas about societal unities, defnitions of old, new and unknown knowledge, as well as practical considerations, were factors that in different way shaped what the continents meant. THE NEW A scheme of continents – usually consisting of the entities ‘Africa,’ ‘America,’ ‘Asia,’ ‘Europe’ and the polar regions – is a part of descriptions about what the world looks like today. In such descriptions, the continents are often treated as existing outside of history. However, like other concepts, the meaning and sig- nifcance of these concepts have changed drastically over time and between con- AND THE texts. -

Decolonization and Beginnings of Swedish Aid

Decolonization and beginnings of Swedish aid http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.naip100004 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Decolonization and beginnings of Swedish aid Author/Creator Sellström, Tor Publisher Nordiska Afrikainstitutet (Uppsala) Date 1999 Resource type Articles Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Sweden, Southern Africa (region) Coverage (temporal) 1960-1970 Source Nordiska Afrikainstitutet (Uppsala) Relation Sellström, Tor. Sweden and national liberation in Southern Africa, Vol. I. Nordiska -

The Growth and Development of Multinational Enterprises

IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM) e-ISSN: 2278-487X, p-ISSN: 2319-7668. Volume 22, Issue 5. Ser. VIII (May. 2020), PP 45-56 www.iosrjournals.org The growth and development of multinational enterprises. Frances N. Madu, Reverend Father, Dr, Anthony Igwe, VictorIfeanyi, Ikezue Student, Department of managementFaculty of business Administration,University of Nigeria Nsukka, Enugu Campus Department of management,Faculty of business Administration,University of Nigeria Nsukka, Enugu Campus StudentDepartment of management,Faculty of business Administration,University of Nigeria Nsukka, Enugu Campus Abstract: The growth and development of Multinational Enterprises has contributed greatly to export based industrialization, capital formation, competitiveness, research, development and technology, poverty alleviation and empowerment generation. Multinational Corporation is convoluted with the history of colonialism, some critics believe that international trade and exploitation were used to facilitate colonialism through creation of colonial trading post, which is today’s Multinational Enterprises. The effect of corporate colonial exploitation has been proven to be long lasting and far reaching, which led to current causes of contemporary global income and social inequality. The objectives of the study is to ascertain the positive impact of growth of multinational enterprises in global economy. The study reveals that MNCs contributed significantly to the economic growth of some developing countries and there has been a significant -

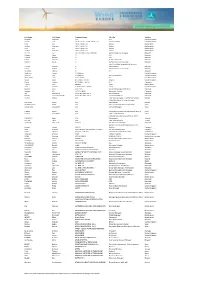

Last Name First Name Company Name Job Title Country Kennedy

Last Name First Name Company Name Job Title Country Kennedy Matthew 1CSI CEO United Kingdom Brown Tom 2H OFFSHORE ENGINEERING LTD Senior Engineer United Kingdom Roos Jan 2MOFFSHORE BV Advisor Netherlands Hardon Maarten 2MOFFSHORE BV Advisor Netherlands Roos Jan 2MOFFSHORE BV Advisor Netherlands Hardon Maarten 2MOFFSHORE BV Advisor Netherlands PETERS Luc 3B-THE FIBREGLASS COMPANY Technical Service Manager Belgium Palmers Geert 3E CEO Belgium Coppye Werner 3E CTO Belgium Pianta Martina 3E Product Manager Belgium Mertiris Vasilis 3E Technical Account Manager Belgium Lead Consultant International Business Estrada Santiago 3E Development Belgium Fripiat Michel 3E Technical Account Manager Belgium De Vylder Thomas 3E CEO Belgium Anderson Lauren 4C Offshore United Kingdom RUSSELL Tom 4C Offshore Press Coordinator United Kingdom ANDERSON Chris 4C OFFSHROE CEO United Kingdom Brown Julian 8.2 AARUFIELD LTD Director United Kingdom Dugué Charles 8.2 CONSULTING AG CEO Germany 't Hooft Jaap 8WINDS Head Netherlands Heap Richard A WORD ABOUT WIND Editor United Kingdom Nielsen Gina A2SEA A/S Senior Marketing Coordinator Denmark Siddiqui Mo. AACTIO GMBH Managing Director Germany Slot René M. M. AALBORG UNIVERSITY PhD candidate Denmark Nielsen Jannie Sønderkær AALBORG UNIVERSITY Assistant Professor Denmark LASOTA Michal ABB Area Sales Manager - Transformer Service Poland Global Marketing & Sales Manager - PRYLINSKI Pawel ABB Renewables Poland Pacheco Ramos Pablo ABB Shell Transformer Product Manager Spain Gracia Abad Juan Pedro ABB Account Manager Spain -

Afro-Swedish Artistic Practices and Discourses in and out of Sweden: a Conversation with Ethnomusicologist Ryan T

Afro-Swedish Artistic Practices and Discourses in and out of Sweden: A Conversation with Ethnomusicologist Ryan T. Skinner Beth Buggenhagen, Ryan Thomas Skinner Africa Today, Volume 64, Number 2, Winter 2017, pp. 92-107 (Article) Published by Indiana University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/689043 Access provided at 24 Mar 2020 17:27 GMT from Indiana University Libraries Afro-Swedish Artistic Practices and Discourses in and out of Sweden: A Conversation with Ethnomusicologist Ryan T. Skinner Beth Buggenhagen Sweden has long been known for its tolerance and openness. During the twentieth century, Swedish missionaries paved the way for Africans to migrate to Sweden, Swedish political figures campaigned for decoloniza- tion, and by the 1970s, Sweden was attracting people fleeing war-torn areas such as the Horn of Africa (Kubai 2016; Kushkush 2016). Yet recently, Sweden has had to contend with a sharp increase in the numbers of immi- grants, refugees, and asylum seekers. Once a nation with one of the most progressive stances on migration, it reversed its immigration policy in 2015, in part responding to the unprecedented numbers of families migrating to Europe from Syria, West Africa, and elsewhere. Sweden began to control its borders with Denmark and to admit only the minimum number of refugees required by its EU membership (Russo 2017). This contemporary conjuncture has fueled debates in Sweden over race, racial identity, and national belonging. These debates are especially pertinent to young people who were born in Sweden and whose parents were born in Africa and who increasingly identify as Afro-Swedes (afrosvensk). -

Filip Batselé Omnes Homines Aut Liberi Sunt Aut Servi

Studies in the History of Law and Justice 17 Series Editors: Mortimer Sellers · Georges Martyn Filip Batselé Liberty, Slavery and the Law in Early Modern Western Europe Omnes Homines aut Liberi Sunt aut Servi Studies in the History of Law and Justice Volume 17 Series Editors Mortimer Sellers University of Baltimore, Baltimore, MD, USA Georges Martyn Law Faculty, University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium Editorial Board António Pedro Barbas Homem, Faculty of Law, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal Emmanuele Conte, Facolta di Giurisprudenza, Università degli Studi Roma Tre, Roma, Italy Maria Gigliola di Renzo Villata, Law & Legal History, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italy Markus Dirk Dubber, Faculty of Law, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada William Ewald, University of Pennsylvania Law School, Philadelphia, PA, USA Igor Filippov, Faculty of History, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia Amalia Kessler, Stanford Law School Crown Quad, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA Mia Korpiola, Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, Helsinki, Finland Aniceto Masferrer, Faculty of Law, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain Yasutomo Morigiwa, Nagoya University Graduate School of Law, Tokyo, Japan Ulrike Müßig, Universität Passau, Passau, Germany Sylvain Soleil, Faculté de Droit et de Science Politique, Université de Rennes, Rennes, France James Q. Whitman, Yale Law School, New Haven, CT, USA The purpose of this book series is to publish high quality volumes on the history of law and justice. Legal history can be a deeply provocative and influential field, as illustrated by the growth of the European universities and the Ius Commune, the French Revolution, the American Revolution, and indeed all the great movements for national liberation through law. -

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies Title Intersecting Worlds: New Sweden’s Transatlantic Entanglements Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2j51x0t3 Journal Journal of Transnational American Studies, 7(1) Authors Fur, Gunlög Naum, Magdalena Nordin, Jonas M. Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/T871030644 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SPECIAL FORUM Intersecting Worlds: New Sweden’s Transatlantic Entanglements GUNLÖG FUR, MAGDALENA NAUM, AND JONAS M. NORDIN Introduction The colony of New Sweden (1638–1655) continues to attract considerable scholarly interest in Sweden and the United States.1 In historiographies, especially those published in the last century, and in popular perception, the colony is often seen as an anomaly, supposedly lacking the prejudices and violence associated with European intrusion in the New World, and as a failure due to its transience. Simultaneously, a sense of pride is often expressed when the colony is mentioned. In Sweden, a national ‘we’ is often invoked to describe New Sweden as “our colony” or “our colonial adventure.”2 The most recent study on Swedish colonial history, journalist Herman Lindqvist’s 2015 book Våra kolonier—de vi hade och de som aldrig blev av (Our Colonies—Those We Had and Those That Never Came to Be) is a case in point. Descendent communities also persist in seeing the colony as the first permanent settlement along the Delaware River and as a peaceful enterprise, using this perception to style themselves as tracing their roots as far back as the English settlers and yet having a different, guiltless heritage. -

Sources for the Mutual History of Ghana and the Netherlands An

Sources for the Mutual History of Ghana and the Netherlands An annotated guide to the Dutch archives relating to Ghana and West Africa in the Nationaal Archief, 1593–1960s Sources for the Mutual History of Ghana and the Netherlands An annotated guide to the Dutch archives relating to Ghana and West Africa in the Nationaal Archief, 1593–1960s Michel R. Doortmont & Jinna Smit LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This book is printed on acid-free paper. A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978 90 04 15850 4 © 2007 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Map 5: Forts and castles of the Coast of Ghana was reproduced with the kind permission of SEDCO Publishers of Accra, Ghana. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints BRILL, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to: The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. Printed in the Netherlands Contents ix Tables, charts, maps, and figures xiii Abbreviations xv Acknowledgements xvii Preface by the director of the Nationaal Archief 1 Introduction 1 Background of the guide 7 Outline of the guide 14 Bibliographical notes 17 Part I: Archial Guide 1. -

Social Aims of Finance Rediscovering Varieties of Credit in Financial Archives

Social Aims of Finance Rediscovering varieties of credit in financial archives Editors Anna Cantaluppi, Chloe Colchester, Lilia Costabile, Carmen Hofmann, Catherine Schenk and Matthias Weber Social Aims of Finance Social Aims of Finance Rediscovering varieties of credit in financial archives © eabh, Frankfurt am Main, 2020 All rights reserved. Cover photo: Headquarters of Istituto delle Opere Pie di San Paolo, early 20th century. Copyright: Torino, Archivio Storico della Compagnia di San Paolo. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Produced and distributed by eabh (The European Association for Banking and Financial History e.V.) in cooperation with Fondazione 1563 per l’Arte e la Cultura della Compagnia di San Paolo. Editors: Anna Cantaluppi, Chloe Colchester, Lilia Costabile, Carmen Hofmann, Catherine Schenk and Matthias Weber The papers included in this volume are a selection of those presented at a joint eabh and Fondazione 1563 conference in 2018 in Turin, Italy. The title of the conference was ‘Social Aims of Finance’. The title of the workshop was ‘Good Archives’. The conference and the workshop in Turin were organised with the support of Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo. ISBN 978-3-9808050-7-0 ISSN 2303-9450 License CC BY NC ND Other titles in this series Clement, P., C. Hofmann, J. Kunert (eds.) (2018), ‘Inflation, Money, Output’ (Frankfurt am Main). Ikonen, V. and D. Ross (eds.) (2014), ‘The Critical Function of History in Banking and Finance’, (Frankfurt am Main). -

Forts, Castles and Society in West Africa: Gold Coast and Dahomey, 1450- 1960 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018 (1-32)

Osei-Tutu, J. K. (Ed.) Forts, Castles and Society in West Africa: Gold Coast and Dahomey, 1450- 1960 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018 (1-32) Introduction: Forts, Castles, and Society in West Africa John Kwadwo Osei-Tutu NTNU Post-print (akseptert fagfelle vurdert versjon) Like their counterparts in Europe, the forts and castles (fortresses) of West Africa were military installations that were erected to protect the specific economic and political interests of their owners. In the West African case, these were the European imperial governments and the respective trading companies operating under royal charters. Remnants of trade forts and castles on the West African littoral are among the buildings in the region that elicit both historical and 1 architectural interest. Though they evoke memories of dastardly undertakings during centuries of Afro-European commercial interaction, their resilient presence today makes forceful and varied impressions on the emotion scape of all types of visitors. The inclusion of these forts and castles on the UNESCO World Heritage List underscores the recognition of their historical value 2 both as ‘irreplaceable sources of life and inspiration’ and as memorial sites of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Even more paradoxical is their post-colonial status as ‘African Heritage’ that is owned by and managed for Africans by their governments. In effect, the buildings have a presence of their own that is separate from, and yet linked to, their historical provenance, uses, and meanings. For the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board (GMMB), the forts and castles are World Heritage sites because their presence in West Africa serves as a reminder of the capacity of humans to combine creativity, aesthetics, instrumentality, and cruelty in one object.