Tidal Rhythms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hilbert Circle Theatre

HILBERTCIRCLETHEATRE KRZYSZTOFURBAŃSKI MUSIC DIRECTOR | JACKEVERLY PRINCIPAL POPS CONDUCTOR Vadim Gluzman Plays Bruch Bronfman Plays Beethoven Sibelius Symphony No. 5 Music of U2 Side-by-Side The Sounds of Simon & Garfunkel MARCH | VOLUME 5 Jump in, IT’SJump PERFECT in, From diving into our heated pool to joining neighbors for a day trip From divingIT’S into our heated PERFECTpool to joining neighbors for a day trip Careful planning, talent and passion are on to taking a dance class, life feels amazingly good here. Add not-for- Fromto taking diving IT’Sa dance into our class, heated life feels PERFECTpool amazingly to joining goodneighbors here. for Add a day not-for- trip pro t ownership, a local board of directors, and CCAC accreditation, display at today’s performance. proFromto t takingownership, diving a danceinto a our local class, heated board life feels pool of directors,amazingly to joining andgood neighbors CCAC here. forAddaccreditation, a daynot-for- trip and Marque e truly is the place to be. proto ttaking ownership, a dance a local class, board lifeand feels ofMarque directors,amazingly e and trulygood CCAC ishere. the accreditation, Add place not-for- to be. pro t ownership, a local board of directors, and CCAC accreditation, At Citizens Energy Group, we understand the value of working hard and Marque e truly is the place to be. behind the scenes to deliver quality on a daily basis. We strive to To learn more, call, visit our websiteand Marque or stop e truly by isour the community. place to be. replicate that ensemble effort in our work and are proud to support To learn more, call, visit our website or stop by our community. -

PROGRAM Thank You to Our Sponsors

Symphony Number One returns on Sunday, November 20, 2016, 6:00 pm at Emmanuel Episcopal Church 811 Cathedral St., Baltimore, MD 21201 for Beethoven’s Kitchen: Piano Quintets featuring Elizabeth Hill, Piano SYMPHONY NUMBER ONE Nikita Borisevich, Violin Kristen Bakkegard, Violin Jordan Randall Smith, Music Director Colin Webb, Viola Joe Isom, Cello SEASON 2 Nicholas Bentz, Featured Composer Song of the Earth St. Ignatius Catholic Church Learn more at www.symphonynumber.one Saturday, November 5, 2016, 8:00 pm Sunday, November 6, 2016, 3:00 pm PROGRAM Thank you to our Sponsors Song of the Earth Thank you to our Sponsors Personnel Advocates (100+) Bill Smyth Christina Muncey Violin Anonymous Michael Sturgis Jesse Page Nikita Borisevich, Daniel & Janne Heifetz Concertmaster Jessica Abel James Turner Russell Perry Hanbing Jia Trevor Auman Chris Walls Mike & Marla Porter Donald Benton Viola Loren Western Brian & Heather Reardon Pipier Bewlay Karin Kilper, Principal Viola Ryan Williams Jeanette Rosenberg J Andrew Cerda Brigette Willner Cynthia Sambataro Cello Robert & Gayle Susan K. Wright Alyssa Sapia Michael Newman, Associate Principal Cello Chesebro Amy Schardein Dorothy R. Coby Supporters ($50+) Elizabeth Sherbow Contrabass Huxley Conklin Anonymous Ellen Shrum Michael Rittling, Principal Contrabass Janis Cookson Sergio Acosta Marilois Snowman Robin Daniel T. Nichelle Appleby Michael D. Terry Flute Michael Everson Karen Bakkegard Brandy Triplett Willie Santiago Vern C. Falby Kristi Barnes Alida Woods Denyce Graves Catherine Boerner Ari Yoshioka -

EAS 23 July 2020 Program.Pdf

Green Mountain Online Emerging Artists Series Thursday, July 23, 2020 7:30 pm EDT GMCMF Emerging Artists YouTube Channel Suite No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011 Johann Sebastian Bach Prelude (1685-1750) Todd Humphrey, cello Suite No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1010 Johann Sebastian Bach Allemande Courante Matthew Wiest, cello Sonata No. 2 in A minor, BWV 1003 Johann Sebasitan Bach Grave Luciano Marsalli, violin Caprice in C minor, Op. 1, no. 4 Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840) Simon Ho Yin Cheng, violin Caprice in A minor, Op. 1, no. 5 Niccolò Paganini Abigail Yoon, violin Capricen B flat major, Op. 1, no. 13 Niccolò Paganini Jessie Zimmermann, violin Introduction and Allegro, Op. 44 Miklós Rózsa (1907-1995) Ashley Park, viola Suite No. 1 in G minor, Op. 131d Max Reger Molto sostenuto (1873-1916) Vivace Andante sostenuto Molto vivace Colin Henley, viola Sonata, Op. 27, No. 5 Eugène Ysaÿe L'Aurore (1858-1931) Danse rustique Maitreyi Muralidharan, violin Piano Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 14 Sergei Prokofiev Allegro, ma non troppo (1891-1953) Sofia Marina, piano Fantasiestücke, Op. 12 Robert Schumann In der Nacht (1810-1856) Fabel Traumes Wirren Ende vom Lied Ellie Taylor, piano Todd Humphrey, 22, is from Atlanta, Georgia. He completed his undergraduate degree at Florida State University where he studied with Greg Sauer. At Florida State, Todd served as principal cellist of the University Philharmonia Orchestra and was cellist of the Lux String Quartet. This ensemble was known for its heartfelt and engaging performances along with its numerous community outreach events. Currently Todd is completing his masters at Miami University of Ohio where he studies with Sarah Kim. -

Timelapse Variations Final Draft

UCLA Contemporary Music Score Collection Title Timelapse Variations Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8nr7s11j Author Draper, Natalie Publication Date 2020 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Timelapse Variations Natalie Draper (2016) Dedication: Timelapse Variations is dedicated to Jordan Randall Smith and Symphony Number One. Many thanks for the opportunity. Instrumentation: Flute Oboe Clarinets (Bb and bass) Bassoon Horn in F Snare Drum Kick Drum Piano Violin I Violin II Viola Violoncello Contrabass Program Notes: Timelapse Variations (2016), for chamber orchestra, is a musical reflection on the timelapse technique in film. I have always been fascinated by how change and growth are perceived in timelapse videos. For me, the timelapse technique, with its surreal perception of change, distances the audience from the image, allowing for a vastly removed perspective--almost as if you are witnessing life from above. The image inherently becomes a meditation on the passage of time itself. In this way, Timelapse Variations is a meditation on musical change and is perhaps more of a soundscape than a traditional symphonic narrative. The piece has several sections, all of which incorporate a variety of processes of gradual change. Many thanks to Symphony Number One for the opportunity to write this piece. - Natalie Draper Performance Notes: This piece is all about gradual change. Close attention should be paid to dynamics and instrument balance. Gestures pop out of the fabric of the work. Overall the piece should have a pedaled, legato sound, without being too mushy. Natalie Draper Timelapse Variations Moderately, (q=72) espress. 3 Flute ° 2 3 2 j &4 ∑ ∑ 4 ∑ 4 ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Œ œ bœ p espress. -

Building Bridges Through Music: a Recording and Performance Collaboration with Adult Composers, Young Soloists, and Collegiate Band Accompaniment

Building Bridges through Music: A Recording and Performance Collaboration with Adult Composers, Young Soloists, and Collegiate Band Accompaniment by Melanie Jane Brooks A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved April 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Gary W. Hill, Co-Chair Jason Caslor, Co-Chair Melita Belgrave Amy Holbrook Deanna Swoboda ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 ABSTRACT Although music is regarded as a universal language, it is rare to find musicians of different ages, ability levels, and backgrounds interacting with each other in collaborative performances. There is a dearth of mixed-ability-level wind band and string orchestra repertoire, and the few pieces that exist fail to celebrate the talents of the youngest and least-experienced performers. Composers writing music for school-age ensembles have also been excluded from the collaborative process, rarely communicating with the young musicians for whom they are writing. This project introduced twenty-nine compositions into the wind band and string orchestra repertoire via a collaboration that engaged multiple constituencies. Students of wind and string instruments from Phoenix’s El Sistema-inspired Harmony Project and the Tijuana-based Niños de La Guadalupana Villa Del Campo worked together with students at Arizona State University and composers from Canada, Finland, and across the United States to learn and record concertos for novice-level soloists with intermediate-level accompaniment ensembles. This project was influenced by the intergenerational ensembles common in Finnish music institutes. The author provides a document which includes a survey of the existing concerto repertoire for wind bands and previous intergenerational and multicultural studies in the field of music. -

2018 Co-Directors

Illinois State University RED NOTE new music festival March 26th – March 29th, 2018 co-directors , distinguished guest composer , distinguished guest composer , guest performers CALENDAR OF EVENTS MONDAY, MARCH 26TH 8 pm, Center for the Performing Arts The Festival opens with a concert featuring the Illinois State University Wind Symphony and Illinois State University choruses. Professor Anthony Marinello conducts the ISU Wind Symphony in a performance of the winning work in this year’s Composition Competition for Wind Ensemble, Patrick Lenz’s Pillar of Fire. The Wind Symphony also performs guest composer William Bolcom’s Concerto for Soprano Saxophone with ISU faculty Paul Nolen, and the world premiere of faculty composer Martha Horst’s work Who Has Seen the Wind? The ISU Concert Choir and Madrigal Singers, conducted by Dr. Karyl Carlson, perform the winning piece in the Composition Competition for Chorus, Wind on the Island by Michael D’Ambrosio, as well as William Bolcom’s Song for Saint Cecilia’s Day. TUESDAY, MARCH 27TH 7:30 pm, Kemp Recital Hall ISU students and faculty present a program of works by featured guest composers Gabriela Lena Frank and William Bolcom. The concert will also include the winning work in this year’s Composition Competition for Chamber Ensemble, Downloads, by Jack Frerer. WEDNESDAY, MARCH 28TH 7:30 pm, Kemp Recital Hall Ensemble Dal Niente takes the stage to perform music of contemporary European composers, including Salvatore Sciarrino, Kaija Saariaho, and György Kurtag. THURSDAY, MARCH 29TH 7:30 pm, Kemp Recital Hall The Festival concludes with a concert of premieres by the participants in the RED NOTE New Music Festival Composition Workshop: James Chu, Joshua Hey, Howie Kenty, Joungmin Lee, Minzuo Lu, Mert Morali, Erik Ransom, and Mac Vinetz. -

WIND INSTRUMENT USAGES in the SYMPHONIES of GUSTAV MAHLER ' by Donald Irvin Caughill a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SC

Wind instrument usages in the symphonies of Gustav Mahler, by Donald Irvin Caughill Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Caughill, Donald I. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 04:43:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318086 WIND INSTRUMENT USAGES IN THE SYMPHONIES OF GUSTAV MAHLER ' by Donald Irvin Caughill A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the. Requirements For the Degree of . MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1972 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has heen submitted in. partial fulfillment of re- • guirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that, accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. 'SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS.DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: E. -

Kennesaw State University Wind Ensemble Presents

program Wednesday, November 18, 2015 at 8:00 p.m. Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Forty-fourth Concert of the 2015-16 Concert Season Kennesaw State University Wind Ensemble presents "PREMIERES!" David T. Kehler, conductor Debra Traficante, guest conductor Roger Zare, featured guest composer RON NELSON (b. 1929) Rocky Point Holiday (1969) Debra Traficante, guest conductor ROGER ZARE (b. 1985) Tangents (2015) (*World Premiere) ROBERT SPITALL (b. 1963) Consort for Ten Winds (2005) I. Jeux II. Aubade III. Sautereau Intermission ANDREW BOSS (b. 1988) Tetelestai - A Symphony for Wind Ensemble (2014) (*Georgia Premiere) I. Homage II. Toccata III. Interlude and Finale program notes Rocky Point Holiday | Ron Nelson Ron Nelson received his Bachelor of Music degree in 1952, the Master’s degree in 1953, and the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in 1956, all from the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester. He also studied in France at the Ecole Normale de Musique and at the Paris Conservatory under a Fulbright Grant in 1955. Dr. Nelson joined the Brown University faculty the following year, and taught there until his retirement in 1993. In 1991, Dr. Nelson was awarded the Acuff Chair of Excellence in the Creative Arts, the first musician to hold the chair. In 1993, hisPassacaglia (Homage on B-A-C-H) made history by winning all three major wind band compositions – the National Association Prize, the American Bandmasters Association Ostwald Prize and the Sudler International Prize. He was awarded the Medal of Honor of the John Philip Sousa Foundation in Washington, DC, in 1994. -

Concerto Repertoire

SEAN MEYERS, saxophonist Biography 2015-2016 Praised by the Baltimore Sun for his “technical aplomb and keen expressive nuance,” saxophonist Sean Meyers performs as a soloist and collaborative artist across the Eastern U.S. and beyond. He has commissioned more than a dozen new compositions for saxophone, including the Concerto for Alto Saxophone and Chamber Orchestra by Andrew Boss, which he premiered and recorded in Baltimore in September 2015. Other world premieres include James Young’s Rainbow Shark for saxophone quartet, which was presented in collaboration with a multimedia art installation at the Maryland Institute College of Art. The composer and Sean’s saxophone quartet also presented the piece in a lecture recital at the Johns Hopkins University’s Meet the Musician: Today’s Classical Musician seminar and performed excerpts on the Academy Art Museum’s Music at Noon concert series in Easton, MD. Sean has been a featured performer on several Peabody Conservatory composition department recitals, and he has been praised by composers for the “eagerness, kindness, and pure excellence with which [he] gobble[s] up new works.” Most recently, he has joined a consortium supporting a new musical composition for saxophone and soprano voice by composer and arts entrepreneur Kevin Clark, with a regional premiere planned for later this year. Sean’s repertoire also encompasses masterpieces by renowned composers ranging from Bolcom to Piazzolla. He has performed extensively in the Baltimore-D.C. area in traditional and non-traditional venues, and his upcoming recital at the Peabody Conservatory will feature prominent musical works for saxophone and piano by Robert Muczynski, Michael Djupstrom, William Bolcom, and William Albright. -

Biographies of Composers & Presenters

BIOGRAPHIES OF COMPOSERS & PRESENTERS Admiral, Roger Canadian pianist Roger Admiral performs solo and chamber music repertoire spanning the 18th through the 21st century. Known for his dedication to contemporary music, Roger has commissioned and premiered many new compositions. He works regularly with UltraViolet (New Music Edmonton) and Aventa Ensemble (Victoria), and performs as part of Kovalis Duo with Montreal percussionist Philip Hornsey. Roger also coaches contemporary chamber music at the University of Alberta. Recent performances include Gyorgy Ligeti’s Piano Concerto with the Victoria Symphony Orchestra, the complete piano works of Iannis Xenakis for Vancouver New Music, a recital with baritone Nathan Berg at Lincoln Center’s Great Performers Series (New York City), and recitals for Curto-Circuito de Música Contemporânea Brazil with saxophonist Allison Balcetis, as well as solo recitals in Bratislava, Budapest, and Wroclaw. Roger can be heard on CD recordings of piano music by Howard Bashaw (Centrediscs) and Mark Hannesson (Wandelweiser Editions). Alexander, Justin Justin Alexander is an Assistant Professor of Music at Virginia Commonwealth University where he teaches Applied Percussion Lessons, Percussion Methods and Techniques, Introduction to World Musical Styles, Music and Dance Forms, and directs the VCU Percussion Ensemble. Justin is a founding member of Novus Percutere, with percussionist Dr. Luis Rivera, and The AarK Duo, with flutist Dr. Tabatha Easley. Recent highlights include collaborative performances in Sweden, Australia, the Percussive Arts Society International Convention, and at the 6th International Conference on Music and Minimalism in Knoxville, Tennessee. As a soloist, Justin focuses on the creation of new works for percussion through commissions and compositions, specifically focusing on post-minimalist/process/iterative keyboard music, non-western percussion, and drum set. -

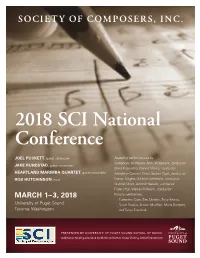

2018 SCI National Conference

SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS, INC. 2018 SCI National Conference JOEL PUCKETT, guest composer Featuring performances by Symphony Orchestra, Anna Wittstruck, conductor JAKE RUNESTAD, guest composer Wind Ensemble, Gerard Morris, conductor HEARTLAND MARIMBA QUARTET, guest ensemble Adelphian Concert Choir, Steven Zopfi, conductor ROB HUTCHINSON, host Dorian Singers, Kathryn Lehmann, conductor Clarinet Choir, Jennifer Nelson, conductor Flute Choir, Wendy Wilhelmi, conductor MARCH 1–3, 2018 Faculty performers: Catherine Case, Tim Christie, Tracy Knoop, University of Puget Sound Dawn Padula, Alistair MacRae, Maria Sampen, Tacoma, Washington and Tanya Stambuk PRESENTED BY UNIVERSITY OF PUGET SOUND SCHOOL OF MUSIC Additional funding provided by Matthew Norton Clapp Visiting Artist Endowment SCHOOL OF MUSIC presents 2018 SCI NATIONAL CONFERENCE March 1–3, 2018 University of Puget Sound Tacoma, Washington Rob Hutchinson, host Joel Puckett, guest composer Jake Runestad, guest composer featuring performances by Puget Sound Symphony Orchestra Puget Sound Wind Ensemble Adelphian Concert Choir Dorian Singers Puget Sound Clarinet Choir Puget Sound Flute Choir 2018 Society of Composers, Inc., National Conference, p. 2 Contents Welcome from Rob Hutchinson, Conference Host p. 3 Welcome from Keith Ward, Director, School of Music p. 4 Biographical summary of Joel Puckett, guest composer p. 5 Biographical summary of Jake Runestad, guest composer p. 6 Concert programs p. 7 Biographical information for composers and guest performers p. 28 Conference Schedule Thursday, March 1 6:30 – 7:30 p.m. Registration MUSIC BUILDING FOYER 7:30 p.m. Concert 1: Heartland Marimba Quartet SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL Friday, March 2 9–10 a.m. Registration and Coffee MUSIC BUILDING FOYER 10 a.m. Concert 2: Chamber Music 1 SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL Noon–2 p.m. -

Edition 1 | 2018-2019

WHAT’S INSIDE CONCERTS Masterworks Chamber Music 30 RACH 3 38 Awet Andemicael Sings Famous Barouqe Arias 47 Ode to America! 42 Magnetic South 1 53 Mendelssohn & Grieg “Contrasts” 79 Beethoven’s 5th 52 Chamber Music at The City Gallery Pops Special Events 34 A Tribute to Louis and Ella with Byron Stripling 63 Holiday Brass with Doc Severinsen and Phil Smith 73 Swingin’ Christmas with Tony DeSare 67 Holy City Messiah 76 Holiday Pops 4 ..........House Notes 18.........CSO Chorus 6 ..........Musicians 22 .......Charleston Symphony 8 ..........Guest Musician Sponsors Orchestra League, Inc. 9 ..........Board of Directors 26 .......Educational Programs 11 ..........Administration 28 .......Musician Roster 13 .........Letter from Executive Director 84 .......CSOGo Members 14 .........Music Director 85 .......Membership Benefits 16 ........Principal Pops Conductor 86 .......Donor Recognition 17 .........From the Symphony 89 .......In Honor/In Memory 92 .......Guest Musician Hosts/In-Kind Gifts ADVERTISING: Onstage Publications This playbill program template is published in association with Onstage Publications, 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 1612 Prosser Avenue, Dayton, Ohio 45409. This playbill program template may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. Onstage e-mail: [email protected] Publications is a division of Just Business!, Inc. Contents © 2018. All rights reserved. www.onstagepublications.com Printed in the U.S.A. CharlestonSymphony.org 3 HOUSE NOTES Thank you for attending this performance of the Charleston Symphony. Here are some tips and suggestions to enhance the concert experience for everyone. TICKET INFORMATION STUDENT DISCOUNTS Students ages 6-22 may take advantage of the following discounts. Some concerts are excluded INDIVIDUAL CONCERT TICKETS or have special pricing noted on the Charleston Online: Symphony website.