Downloaded from Pubfactory at 09/23/2021 07:54:21PM Via Free Access 188 Chapter 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FORD MADOX FORD's ROLE in the ROMANTICIZING of the BRITISH NOVEL a C C E P T E D of T^E Re<3Uirements

FORD MADOX FORD’S ROLE IN THE ROMANTICIZING OF THE BRITISH NOVEL by James Beresford Scott B.A., University of British Columbia, 1972 M.A., University of Toronto, 1974 A Dissertation Submitted In Partial Fulfillment ACCEPTED of T^e Re<3uirements For The Degree Of FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES doctor of PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English a - k k i We**accept this dissertation as conforming TWT1 / / ".... to the recruired standard Dr. C .DDoyle.l^upSr visor fDeoartment of English) Dr/ j/LouisV^ebarKtffiQiiEhr’ffSmber (English) Dr. D . S. jfhatcher, Department Member iEnglish) Dr. J. Mohey^ Outside^ Mem^er (History) Dr. pA.F. Arend, Outside Member (German) Dr. I.B. Nadel, External Examiner (English, UBC) ® JAMES BERESFORD SCOTT, 1992 University Of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. I . i Supervisor: Dr. Charles D. Doyle ABSTRACT Although it is now widely accepted that the Modern British novel is grounded in Romantic literary practice and ontological principles, Ford Madox Ford is often not regarded as a significant practitioner of (and proselytizer for) the new prose aesthetic that came into being near the start of the twentieth century. This dissertation argues that Ford very consciously strove to break away from the precepts that had informed the traditional novel, aiming instead for a non- didactic, autotelic art form that in many ways is akin to the anti-neoclassical art of the British High Romantic poets. Ford felt that the purpose of literature is to bring a reader into a keener apprehension of all that lies latent in the individual sell?— a capacity that he felt had atrophied in a rational, rule-abiding, industrialized culture. -

PDF-Export Per Menü Datei / Als PDF Freigeben

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Boyer, Robert Working Paper How and Why Capitalisms Differ MPIfG Discussion Paper, No. 05/4 Provided in Cooperation with: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG), Cologne Suggested Citation: Boyer, Robert (2005) : How and Why Capitalisms Differ, MPIfG Discussion Paper, No. 05/4, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/19918 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR GESELLSCHAFTSFORSCHUNG MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF SOCIETIES MPIfG Discussion Paper 05/4 How and Why Capitalisms Differ PDF-Export per Menü Datei / Als PDF freigeben.. -

Competence, Knowledge, and the Labour Market. the Role of Complementarities

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gatti, Donatella Working Paper Competence, knowledge, and the labour market: the role of complementarities WZB Discussion Paper, No. FS I 00-302 Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Gatti, Donatella (2000) : Competence, knowledge, and the labour market: the role of complementarities, WZB Discussion Paper, No. FS I 00-302, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/44107 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu discussion paper FS I 00 - 302 Competence, Knowledge, and the Labour Market The role of complementarities Donatella Gatti February 2000 ISSN Nr. -

An Introduction to Varieties of Capitalism

An Introduction to Varieties of Capitalism Peter A. Hall and David Soskice _______________________________________________________________________ Political economists have long been interested in institutional variation across countries. Some regard the institutional differences among nations as deviations from ‘best practice’ that can be expected to decline as countries catch up to the technological and organizational leader. Others see them as the distillation of more durable historical choices for a particular kind of economy and society, since economic institutions are closely linked to the levels of social protection, distribution of income, and collective goods that reflect a nation’s conception of social solidarity. From either perspective, comparative political economy requires conceptual frameworks for identifying and understanding the most important variations in institutions across nations. On such frameworks hang the answers to a range of important questions. Some of these are policy-related. What kinds of macroeconomic, industrial or social policies will improve the performance of the economy? What should governments be expected to do in the face of economic challenges and what defines a state’s capabilities? Others are firm- related. Are there systematic differences in the structure and strategy of companies located in different countries and, if so, what conditions them? How are cross-national differences in the character of innovation to be explained? Institutional differences also affect economic performance. Do some forms of economic organization provide lower rates of inflation and unemployment or higher rates of growth? What are the economic trade-offs to developing one type of political economy rather than another? Finally, there are second-order questions about institutional change and stability of special importance today. -

PO/IE 318 – GERMANY in the GLOBAL ECONOMY IES Abroad Berlin DESCRIPTION: This Course Introduces Students to the German Economi

PO/IE 318 – GERMANY IN THE GLOBAL ECONOMY IES Abroad Berlin DESCRIPTION: This course introduces students to the German economic and political model with a special focus on Germany’s role in the European and global economy. The first part of the course will focus on Germany’s history, economy and politics, while the second part puts more emphasis on contemporary issues and the role of Germany within the European Union (EU). The course will also look into global economic governance, particularly the global trade regime, from the perspective of Germany and the EU. At the end of this course, students will be prepared to assess the specifics of the German economy embedded in Europe and the world: How did Germany become the third largest export economy in the world? What is the role of government for its economic success? How have the Deutschmark and, later, the Euro and the broader process of European integration affected the German economy? How have politics and the ideology of the government affected German economy throughout its history? What is the impact of German trade surpluses on its European and global partners? These are just few of the questions that the class will aim to answer. The interdisciplinary approach of this course, combining political science, economics, history, and international political economy will give students a broad picture of salient topics that determine the German economic model. CREDITS: 3 CONTACT HOURS: 45 LANGUAGE OF INSTRUCTION: English PREREQUISITES: None ADDITIONAL COST: None METHOD OF PRESENTATION: There are no preconditions for enrolling in this course. The lecturer seeks to spark intellectual curiosity and interest in understanding social phenomena by applying an interdisciplinary approach. -

Curriculum Vitae David Soskice

Curriculum Vitae David Soskice 309 Perkins Lib Durham, NC 27708 (email) Education PhD Oxford University 1969 M.A. 1968 Studies Nuffield College, Oxford 1967 Studies Trinity College, Oxford 1964 B.A. (PPE) PPE 1964 Studies Winchester College 1961 Areas of Research Western Europe, Political Economy, and Labor Markets Professional Experience / Employment History London School of Economics Centennial Professor, , 2004−2007 Department of Political Science, Yale University Visiting Professor, , Spring Semester 2004 Berlin (WZB) Research Professor, Wissenschaftszentrum fur Sozialforschung, 2004−2007 (Until retirement, 2007) Duke University Research Professor, Department of Political Science, 2001−2008 each Spring semester European Union Scholar, , March 1999 University of Wisconsin at Madison Marshall−Monnet Lecturer, , September 1999 Australian National University Adjunct Research Professor, Research School of the Social Studies, 1998−2009 University of Trento Guest Professor, Department of Social Sciences, November 1995 to work with Professors Esping−Andersen and Regini University College, University of Oxford Emeritus Fellow in Economics, , 1993 University of Oxford Senior Research Fellow, Institute of Economics and Statistics, 1990−1992 Wissenschaftszentrum fur Sozialforschung, Berlin (WZB) Director, Research Area: Employment and Economic Change, 1990−2001 University College, Oxford; and CUF Lecturer, University of Oxford Fellow (from 1979, the Mynor Fellow) and Tutor in Economics, , 1967−1990 (from 1979, the Mynors Fellow) and Tutor in -

Economic Interests and the Origins of Electoral Systems THOMAS R

American Political Science Review Vol. 101, No. 3 August 2007 DOI: 10.1017/S0003055407070384 Economic Interests and the Origins of Electoral Systems THOMAS R. CUSACK Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin TORBEN IVERSEN Harvard University DAVID SOSKICE Duke University and University of Oxford he standard explanation for the choice of electoral institutions, building on Rokkan’s seminal work, is that proportional representation (PR) was adopted by a divided right to defend its class T interests against a rising left. But new evidence shows that PR strengthens the left and redistribution, and we argue the standard view is wrong historically, analytically, and empirically. We offer a radically different explanation. Integrating two opposed interpretations of PR—–minimum winning coalitions versus consensus—–we propose that the right adopted PR when their support for consensual regulatory frameworks, especially those of labor markets and skill formation where co-specific investments were important, outweighed their opposition to the redistributive consequences; this occurred in countries with previously densely organized local economies. In countries with adversarial industrial relations, and weak coordination of business and unions, keeping majoritarian institutions helped contain the left. This explains the close association between current varieties of capitalism and electoral institutions, and why they persist over time. hy do advanced democratic countries have ments (Iversen and Soskice 2006), higher government different electoral systems? The uniformly spending (Bawn and Rosenbluth 2006; Persson and Waccepted view among comparativists is that Tabellini 2004), less inequality (Crepaz 1998; Rogowski the social cleavages that existed at the start of the and MacRae 2004), and more redistribution (Austen- twentieth century shaped the institutional choices of Smith 2000; Iversen and Soskice 2006). -

Advanced Capitalist Democracies by Torben Iversen and David Soskice CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Advanced Capitalist Democracies CHAPTER 1: By Torben Iversen and David Soskice INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction Much of the literature on advanced capitalist democracies over the past two decades has painted a critical and pessimistic picture of advanced capitalism, and – closely linked – of the future of democracy in advanced societies. In this view, the advanced capitalist democratic state has weakened over time because of globalization and the diffusion of neoliberal ideas. With advanced business seen as major driver and exponent, this has led to liberalization, privatization, deregulation, and intensified global competition. In Esping-Andersen’s striking metaphor, it is markets against politics. This explains, inter alia, why there has been a rise in inequality (labor is weakened) and why this rise has not been countered by increased redistribution. If governments attempted such redistribution, the argument goes, it would cause footloose capital to flee. In Piketty’s hugely influential account, the power of capital to accumulate wealth is governed by fundamental economic laws which democratically elected governments cannot effectively counter. Democratic politics is reduced to symbolic politics; the real driver of economic outcomes is capitalism. In this book we argue that the opposite is true. Over time the advanced capitalist democratic state has paradoxically become strengthened through globalization, and we explain why at length in this book. The spread of neoliberal ideas, we argue, reflects the demand of decisive voters from the middle and upper middle classes to fuel economic growth, wealth, and opportunity in the emerging knowledge economy. The “laws” of capitalism driving wealth accumulation are in fact politically manufactured. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19192-0 - The Selected Letters of Joseph Conrad Edited by: Laurence Davies Excerpt More information INTRODUCTION i Biography frequently relies on diaries and letters, but because few let- ters and no diaries from Joseph Conrad’s first thirty years have sur- vived, reliance goes the other way.1 Even if we had more documents written in his hand, a life as remarkable as his, involving two vocations, several languages, and many polities, needs a fuller introduction than the brief chronologies that begin each section of this volume. All the same, readers well acquainted with his history may care to skip this opening section. Conrad’s story is one both of steadfastness and circumstance. His parents and most of his extended family were devoted to the restora- tion of Polish independence, lost in the partitions of 1782, 1793, and 1795 as Russia, Prussia, and Austria divided up the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth among themselves. He grew up carrying a burden of sacrificial duty, an imperative he admired for its demands on courage and tenacity but, in his life as exile, sailor, author, could never follow absolutely. As he told his close friend Cunninghame Graham, who was mourning the loss of his wife, ‘Living with memories is a cruel business. I – who have a double life one of them peopled only by shadows grow- ing more precious as the years pass – know what that is’ (7 October 1907). He had become a British subject on 19 August 1886, at the age of 29, not only as a practical necessity but as a demonstration of loyalty to a nation whose institutions he admired and whose merchant navy had afforded him a career. -

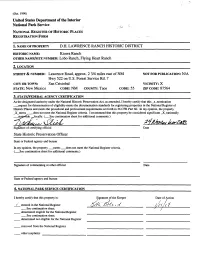

Taos CODE: 55 ZIP CODE: 87564

(Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. NAME OF PROPERTY D.H. LAWRENCE RANCH HISTORIC DISTRICT HISTORIC NAME: Kiowa Ranch OTHER NAME/SITE NUMBER: Lobo Ranch, Flying Heart Ranch 2. LOCATION STREET & NUMBER: Lawrence Road, approx. 2 3/4 miles east of NM NOT FOR PUBLICATION: N/A Hwy 522 on U.S. Forest Service Rd. 7 CITY OR TOWN: San Cristobal VICINITY: X STATE: New Mexico CODE: NM COUNTY: Taos CODE: 55 ZIP CODE: 87564 3. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x_nomination __request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _X_nationally ^locally. (__See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official Date State Historic Preservation Officer State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property __meets does not meet the National Register criteria. (__See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that this property is: Signature of the Keeper Date of Action . entered in the National Register c f __ See continuation sheet. / . determined eligible for the National Register __ See continuation sheet. -

Varieties of Capitalism and Institutional Complementarities in the Political Economy: an Empirical Analysis

B.J.Pol.S. 39, 449–482 Copyright r 2009 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0007123409000672 Printed in the United Kingdom First published online 1 May 2009 Varieties of Capitalism and Institutional Complementarities in the Political Economy: An Empirical Analysis PETER A. HALL AND DANIEL W. GINGERICH* This article provides a statistical analysis of core contentions of the ‘varieties of capitalism’ perspective on comparative capitalism. The authors construct indices to assess whether patterns of co-ordination in the OECD economies conform to the predictions of the theory and compare the correspondence of institu- tions across subspheres of the political economy. They test whether institutional complementarities occur across these subspheres by estimating the impact of complementarities in labour relations and corporate governance on growth rates. To assess the durability of varieties of capitalism, they report on the extent of institutional change in the 1980s and 1990s. Powerful interaction effects across institutions in the subspheres of the political economy must be considered if assessments of the economic impact of institutional reform in any one sphere are to be accurate. The field of comparative political economy has been interested for many years in understanding how differences in the organization of national political economies con- dition aggregate economic performance. Behind such inquiries lies the intuition that more than one economic model can deliver economic success. But what are the central features that distinguish the operation of one political economy from another, and how should countries be categorized along these dimensions of difference? For the developed economies, the answers usually given to these questions in each era have corresponded to the principal challenges confronting those economies. -

From Orientalism to Cultural Capital: the Myth of Russia in British

Bibliography Alekseev, M. P., ‘Shekspir i russkoe gosudarstvo XVI–XVII vv.’, in Shekspir i russkaia kul’tura, ed. M. P. Alekseev (Moscow and Leningrad: Akademia nauk, 1965), pp. 784–805. Alston, Charlotte, Russia’s Greatest Enemy?: Harold Williams and the Russian Revolu- tions (New York: Tauris, 2007). Amfiteatrov, Aleksandr V., ‘Gorestnye zamety’,Novaia russkaia zhizn’ (Gel’singfors) 221 (27 September 1921), p. 222 (28 September 1921). Anderson, M. S., British Discovery of Russia, 1553–1815 (London: St. Martin’s Press, 1958). Archer, William, ‘The Theatre’,World , 11 April 1905, p. 622. Aristotle, ‘Nicomachean Ethics’, in Complete Works of Aristotle, ed. Jonathan Barnes (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995), II, pp. 729–867. ‘Arkay’, The Tatler, 7 April 1920. Arnold, Matthew, ‘Count Leo Tolstoi’, Fortnightly Review 42 (1887), pp. 783–99. Ashton, Rosemary, Victorian Bloomsbury (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012). Asquith, Cynthia, Portrait of Barrie (London: James Barrie, 1955). Atheling, William [Ezra Pound], ‘At the Ballet’, New Age, 16 October 1919, p. 412. Baring, Maurice, Landmarks in Russian Literature (London: Methuen and Co, 1910). The Mainsprings of Russia (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1914). Maurice Baring: Restored Selections from His Work, ed. Paul Horgan (London: William Heinemann, 1970). Russian Essays and Stories (London: Methuen & Co, 1908). The Russian People (London: Methuen and Co, 1911). Barrie, J. M., Letters of J. M. Barrie, ed. Viola Meynell (London: Peter Davies, 1942). ‘The Truth of the Russian Dancers’, in A. J. Pischl and Selma Jeanne Cohen, eds, Dance Perspectives 14 (1962), pp. 12–30. Bassinsky, Pavel, Strasti po Maksimu: deviat’ dnei posle smerti (Moscow: Astrel’, 2011).