Your Name Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

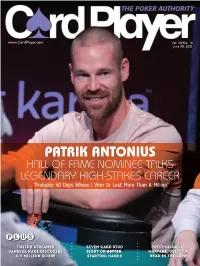

PATRIK ANTONIUS HALL of FAME NOMINEE TALKS LEGENDARY HIGH-STAKES CAREER “Probably 40 Days Where I Won Or Lost More Than a Million”

www.CardPlayer.com Vol. 34/No. 14 June 30, 2021 PATRIK ANTONIUS HALL OF FAME NOMINEE TALKS LEGENDARY HIGH-STAKES CAREER “Probably 40 Days Where I Won Or Lost More Than A Million” Twitch Streamer Seven Card Stud Psychological Vanessa Kade Discusses Eight-Or-Better: Warfare: Get Your $1.5 Million Score Starting Hands Head In The Game PLAYER_34_14B_Cover.indd 1 6/10/21 10:41 AM PLAYER_14_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 2 6/7/21 8:30 PM PLAYER_14_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 3 6/7/21 8:30 PM Masthead - Card Player Vol. 34/No. 14 PUBLISHERS Barry Shulman | Jeff Shulman Editorial Corporate Office EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Julio Rodriguez 6940 O’Bannon Drive TOURNAMENT CONTENT MANAGER Erik Fast Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 ONLINE CONTENT MANAGER Steve Schult (702) 871-1720 Art [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Wendy McIntosh Subscriptions/Renewals 1-866-LVPOKER Website And Internet Services (1-866-587-6537) CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Jaran Hardman PO Box 434 DATA COORDINATOR Morgan Young Congers, NY 10920-0434 Sales [email protected] ADVERTISING MANAGER Mary Hurbi Advertising Information NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Barbara Rogers [email protected] LAS VEGAS AND COLORADO SALES REPRESENTATIVE (702) 856-2206 Rich Korbin Distribution Information cardplayer Media LLC [email protected] CHAIRMAN AND CEO Barry Shulman PRESIDENT AND COO Jeff Shulman Results GENERAL COUNSEL Allyn Jaffrey Shulman [email protected] VP INTL. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Dominik Karelus CONTROLLER Mary Hurbi Schedules FACILITIES MANAGER Jody Ivener [email protected] Follow us www.facebook.com/cardplayer @CardPlayerMedia Card Player (ISSN 1089-2044) is published biweekly by Card Player Media LLC, 6940 O’Bannon Drive, Las Vegas, NV 89117. -

Official Media Guide

OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE 40th ANNUAL WORLD SERIES OF POKER May 26th- July 15, 2009 Rio Hotel, Las Vegas November Nine – November 7-10 www.worldseriesofpoker.com 1 2009 Media Guide Documents: COVER PAGE ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 PR CONTACT SHEET ................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 GENERAL EVENT INFORMATION: FACT SHEET .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 SCHEDULE..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 SCHEDULE..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 SCHEDULE.................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

2013 National Heads-Up Poker Championship

2013 NATIONAL HEADS-UP POKER CHAMPIONSHIP Round of 64 Round of 32 Round of 16 Quarterfinals Semifinals Championship Semifinals Quarterfinals Round of 16 Round of 32 Round of 64 January 24th January 25th January 25th January 26th January 26th January 26th January 26th January 26th January 25th January 25th January 24th Antonio Esfandiari Joseph Cheong Antonio Esfandiari Joseph Cheong Jennifer Tilly Olivier Busquet Antonio Esfandiari Jean-Robert Bellande Jonathan Duhamel Jean-Robert Bellande Jonathan Duhamel Bruce Miller Matt Glantz Bruce Miller Daniel Cates Eugene Katchalov Chris Moorman Maria Ho Chris Moorman Phil Galfond Carlos Mortensen Phil Galfond Daniel Cates Eugene Katchalov Matt Salsberg Eugene Katchalov Daniel Cates Eugene Katchalov Daniel Cates Faraz Jaka Vanessa Rousso Justin Smith Vanessa Rousso Justin Smith Yevgeniy Timoshenko Elky Grospellier Vanessa Rousso Phil Hellmuth Shaun Deeb Phil Hellmuth Shaun Deeb Phil Hellmuth Andy Frankenberger Mike Sexton Scott Seiver Phil Hellmuth Andy Bloch Chris Moneymaker Kyle Julius Chris Moneymaker Kyle Julius Jason Somervile Scott Seiver David Sands Will Failla Rob Salaburu Scott Seiver David Sands Scott Seiver David Sands Ben Lamb Erik Seidel Barry Greenstein CHAMPION Tom Dwan Barry Greenstein Tom Dwan Barry Greenstein Tom Dwan John Monnette Tom Marchese John Monnette Doyle Brunson Greg Raymer Doyle Brunson Mike Matusow Brian Hastings Viktor Blom Brian Hastings Viktor Blom Brian Hastings Andrew Lichtenberger Matt Matros Mike Matusow Brian Hastings Michael Mizrachi Nick Schulman Mike Matusow Eli Elezra Mike Matusow Eli Elezra David Williams Greg Merson John Hennigan Joe Serock John Hennigan Joe Serock John Hennigan Joe Serock Sam Simon Mohsin Charania Sam Simon Huck Seed David Oppenheim Huck Seed John Hennigan Joe Serock Phil Laak Liv Boeree Phil Ivey Gaelle Baumann Phil Ivey Gaelle Baumann Phil Ivey Dan Smith Isaac Haxton Jason Mercier Justin Bonomo Dan Smith Justin Bonomo Dan Smith. -

Biggest Casino Whales Macau Makes a Big Move in Manila the Biggest Looking Back at Appt Losing Players Nanjing Millions Shut in Online Down History

MAGAZINE THE WORLD’S POKER KING CLUB BIGGEST CASINO WHALES MACAU MAKES A BIG MOVE IN MANILA THE BIGGEST LOOKING BACK AT APPT LOSING PLAYERS NANJING MILLIONS SHUT IN ONLINE DOWN HISTORY POKER IN ASIA 2015 TWELVE STORIES Contents. These losing players deserve our respect and admiration for their sheer perseverance, and above all else, we should remember that they have always been the pillars upon December 2015 // Biggest Online looser which the world of high stakes poker is balanced January February March April THE WORLD’S BIGGEST PROSTITUTION EIGHT PHIL IVEY POKER KING CLUB CASINO WHALES SCANDALS IN MACAU STORIES MACAU MAKES A BIG MOVE IN MANILA Page 03 Page 05 Page 06 Page 07 May June July August THE APRISIANLESS LOOKING BACK AT APPT INTERVIEW: WALLY “THE DREAM” GAMBLING MORE NANJING MILLIONS SOMBERO FROM ASIAN TERRY FAN ENTERTAINEMENT, IS SHUT DOWN POKER PIONEER TO 2015 A TURNING POINT GAME-CHANGER FOR MACAU? Page 08 Page 10 Page 12 Page 14 September October November December ARE INTERNATIONAL THE LEGEND OF THE BIGGEST LOSING 5 FISHY WAYS TO THINK POKER PLAYERS ISILDUR1 IN 7 DATES PLAYERS IN ONLINE ABOUT POKER CHANGING THE HISTORY FACE OF THE ASIAN POKER SCENE? Page 16 Page 18 Page 20 Page 22 January 2015 Adnan Khashoggi Adnan Khashoggi is a gambler that every casino wants walking through their doors. Having spent years as a businessman reportedly involved in the sale of military hardware such as aircraft and weapons, he became a serious high stakes gambler for over 25 years. At one point his fortune was said to exceed $40billion, but eventually, his cheques began to bounce, and casinos came looking for payment. -

Downloaded More Than 900,000 Times Since Philippines Visitation Was Down 3.4%

September 2013 • MOP 30 • ISSN 2070-7681 COVER STORY CONTENTS 8 The Asian Gaming 50 INSIGHTS Show Starter Here it is, our annual ranking of the men and 56 Perhaps the most prolific gaming- women who are having the greatest impact focused inventor in Asia, Jay Chun is on the most dynamic and fastest-growing masterminding a new regional trade gaming market in the world. show to challenge G2E’s dominance. FEATURES Okada’s Philippine Woes Continue 59 Although Universal Entertainment claims it has been cleared of allegations of wrongdoing by the Philippine Economic Zone Authority, the company is pressing on with its internal bribery investigation, as are the Philippine Department of Justice and the US FBI. Headwinds Down Under 60 Crown and Echo claw for an edge in tough markets. The Next Frontier 62 NagaCorp follows Lawrence Ho in pursuing the development of an integrated resort in Russia’s Far East. IN FOCUS Off the Hook 64 LVS has agreed to forfeit $47.4 million to the US government to avoid prosecution for failing to report millions of dollars in money transfers from a gambler linked to drug trafficking. BRIEFS 66 Regional Briefs 68 International Briefs Cover illustration by Rui Rasquinho 70 Events Calendar EDITORIAL Vietnam’s Locals Ban: How It Could End here are more than 92 million people in Vietnam of whom about 50 million or more are adult Tage, and as we know from the success of NagaWorld in neighboring Cambodia, a substantial number of them like a flutter. How much larger would that number be if they didn’t have to leave the country to enjoy one? “We’d actually be sitting on a gold mine,” says Mike Santangelo, chief operating officer of The Grand – Ho Tram Strip. -

2010 Nhupc Brackets

2010 NATIONAL HEADS-UP POKER CHAMPIONSHIP Round of 64 Round of 32 Round of 16 Quarterfinals Semifinals Championship Semifinals Quarterfinals Round of 16 Round of 32 Round of 64 March 5th March 6th March 6th March 7th March 7th March 7th March 7th March 7th March 6th March 6th March 5th PATRIK ANTONIUS JESPER HOUGAARD CHRIS MONEYMAKER ALLEN CUNNINGHAM CHRIS MONEYMAKER ALLEN CUNNINGHAM CHRIS MONEYMAKER ELI ELEZRA LEO WOLPERT ELI ELEZRA LEO WOLPERT ELI ELEZRA ERIC BALDWIN GREG MUELLER ERIK SEIDEL DENNIS PHILLIPS DAVID WILLIAMS ANNETTE DWORSKI DAVID WILLIAMS CHRIS FERGUSON JOE CADA CHRIS FERGUSON ERIK SEIDEL DENNIS PHILLIPS ERIK SEIDEL KARA SCOTT ERIK SEIDEL DENNIS PHILLIPS HUCK SEED DENNIS PHILLIPS ERIK SEIDEL DENNIS PHILLIPS DAN RAMIREZ BROCK PARKER ERICK LINDGREN DOYLE BRUNSON ERICK LINDGREN DOYLE BRUNSON PETER EASTGATE DOYLE BRUNSON PETER EASTGATE JP KELLY PETER EASTGATE DON CHEADLE BERTRAND GROSPELLIER DON CHEADLE PETER EASTGATE ERIK SEIDEL DOYLE BRUNSON STEPHEN QUINN HOWARD LEDERER STEPHEN QUINN PHIL HELLMUTH TED FORREST PHIL HELLMUTH JAMIE GOLD ANNETTE OBRESTAD DARIO MINIERI ANNETTE OBRESTAD JAMIE GOLD ANNETTE OBRESTAD JAMIE GOLD OREL HERSHISER ANNIE DUKE GAVIN SMITH BARRY GREENSTEIN PHIL IVEY CHAMPION BARRY GREENSTEIN PHIL IVEY VANESSA ROUSSO SCOTTY NGUYEN BARRY GREENSTEIN RICHARD EDWARDS SAM FARHA SCOTTY NGUYEN SAM FARHA SCOTTY NGUYEN ANTONIO ESFANDIARI SCOTTY NGUYEN JERRY YANG SHAWN RICE JENNIFER HARMAN JOE HACHEM JENNIFER HARMAN JOE HACHEM ANNIE DUKE JENNIFER TILLY GABE KAPLAN JERRY YANG GABE KAPLAN JERRY YANG GABE KAPLAN JERRY YANG JOHNNY CHAN MIKE MATUSOW SCOTTY NGUYEN ANNIE DUKE DANIEL NEGREANU DARVIN MOON JASON MERCIER DARVIN MOON JASON MERCIER BILL HUNTRESS JASON MERCIER ANNIE DUKE PIETER de KORVER ANDY BLOCH PIETER de KORVER ANNIE DUKE MIKE SEXTON ANNIE DUKE JASON MERCIER ANNIE DUKE PHIL GORDON ANDREW WILSON PHIL GORDON PAUL WASICKA TOM DWAN PAUL WASICKA PHIL LAAK PAUL WASICKA PHIL LAAK GUS HANSEN PHIL LAAK GUS HANSEN JOHN JUANDA GREG RAYMER SUNDAYS ON NBC - BEGINS APRIL 18th, NOON ET. -

Phil Gordons Little Green Book Pdf, Epub, Ebook

PHIL GORDONS LITTLE GREEN BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Phil Gordon,Howard Lederer,Annie Duke | 320 pages | 02 Oct 2006 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781416903673 | English | New York, United States Phil Gordons Little Green Book PDF Book Great insight to one individuals take. He relates what goes through a pro's mind in every situation, whether it's a timely bluff or a questionable call, and helps players calculate their own best moves in the most pressure-fueled of situations. It's good stuff, front to back well, okay, I could have done without the charts; even Gordon himself minimizes their importance as much as possible. Foreword by Chris Ferguson. If you are a pro - skip this book. Phil does a great job of sharing his in-depth knowledge and presents it extremely well without overcomplicating it. Not yet memorized, but no need to keep a poker face when playing on the computer Other editions. Retrieved December 12, I actually bought the book first and was completely impressed. Community Reviews. In Poker: The Real Deal and Phil Gordon's Little Green Book , Phil Gordon -- a world- class player and teacher -- shared the strategies, tips, and expertise he's gleaned during his phenomenally successful career. Very helpful. Dec 17, Ruslan Voronkov rated it really liked it. By clicking 'Sign me up' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to the privacy policy and terms of use. I listened to this book for about 2 weeks straight because I knew I was going to miss things. Millions of dollars change hands thanks to the game each year and if you want to earn your share then you are going to need to understand the math that goes into the game to ensure you can formulate a solid plan of action moving forward. -

Longtime Grinder Ronnie Bardah: 'Poker Found

www.CardPlayer.com Vol. 34/No. 8 April 7, 2021 AJ Benza Talks About The Return Of High Stakes Poker Qing Liu Surges Into The Player Of The Year Lead Strategy: Top Pros Explain Tournament Stack Size Considerations LONGTIME GRINDER RONNIE BARDAH: ‘POKER FOUND ME’ Former Survivor Contestant Kicks Off 2021 With The Largest Score Of His Career PLAYER_34_08_Cover.indd 1 3/18/21 10:47 AM PLAYER_08_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 2 3/16/21 9:39 AM PLAYER_08_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 3 3/16/21 9:39 AM Masthead - Card Player Vol. 34/No. 8 PUBLISHERS Barry Shulman | Jeff Shulman Editorial Corporate Office EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Julio Rodriguez 6940 O’Bannon Drive TOURNAMENT CONTENT MANAGER Erik Fast Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 ONLINE CONTENT MANAGER Steve Schult (702) 871-1720 Art [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Wendy McIntosh Subscriptions/Renewals 1-866-LVPOKER Website And Internet Services (1-866-587-6537) CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Jaran Hardman PO Box 434 DATA COORDINATOR Morgan Young Congers, NY 10920-0434 Sales [email protected] ADVERTISING MANAGER Mary Hurbi Advertising Information NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Barbara Rogers [email protected] LAS VEGAS AND COLORADO SALES REPRESENTATIVE (702) 856-2206 Rich Korbin Distribution Information cardplayer Media LLC [email protected] CHAIRMAN AND CEO Barry Shulman PRESIDENT AND COO Jeff Shulman Results GENERAL COUNSEL Allyn Jaffrey Shulman [email protected] VP INTL. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Dominik Karelus CONTROLLER Mary Hurbi Schedules FACILITIES MANAGER Jody Ivener [email protected] Follow us www.facebook.com/cardplayer @CardPlayerMedia Card Player (ISSN 1089-2044) is published biweekly by Card Player Media LLC, 6940 O’Bannon Drive, Las Vegas, NV 89117. -

Moneymaker Effect and His Marketing Impact to Poker Boom

eXclusive e-JOURNAL ISSN: 1339-4509 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.exclusiveejournal.sk ECONOMY & SOCIETY & ENVIRONMENT Moneymaker effect and his marketing impact to poker boom PhDr. Martin Mudrík, PhD. University of Prešov in Prešov Department of marketing and international trade Konštantínova 16, 080 01 Prešov, Slovakia [email protected] Abstract: This article deals with areas that have been booming in recent years. This is the area that is currently very popular among people of different ages and genders. This game is currently enjoying great popularity, both live version and online version also. It highlights a number of factors that helped this development. Separately points out to the Moneymaker effect that stood in 2003 at the birth of this boom. In the WSOP Main event examples (which is the most popular tournament of the year) clearly points to a rapid increase in this area. There is a lot of money being spent on poker, and that's why it's a hilarious opportunity for investors. Keywords: moneymaker effect; boom; poker; WSOP JEL Classification: C22; C51; Q11; Q13 Acknowledgement: This article is one of the partial outputs of the currently solved research grant VEGA no. 1/0789/17 entitled "Research of e-commerce with relation to dominant marketing practices and important characteristics of consumer behavior while using mobile device platforms.". © 2016 The Author(s). Published by eXclusive e-JOURNAL. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Deal Me In: Twenty of the Worlds Top Poker Pros Share How They Turned Pro by Stephen John

Deal Me In: Twenty of The Worlds Top Poker Pros Share How They Turned Pro by Stephen John Ebook Deal Me In: Twenty of The Worlds Top Poker Pros Share How They Turned Pro currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Deal Me In: Twenty of The Worlds Top Poker Pros Share How They Turned Pro please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 287 pages+++Publisher:::: Phils House Publishing, Inc.; 1 edition (September 1, 2009)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0982455801+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0982455807+++Product Dimensions::::5.5 x 0.8 x 8.5 inches++++++ ISBN10 0982455801 ISBN13 978-0982455 Download here >> Description: Deal Me In showcases 20 of the worlds top poker players as they share their colorful and inspiring stories of how they became professionals. Pokers biggest players, such as Phil Ivey (2009 WSOP Main Event Finalist), Johnny Chan, Phil Hellmuth , Doyle Brunson and Daniel Negreanu give first-person accounts of their personal journeys and the key moments in their rise to the top of the poker pantheon. These stories will teach, inspire and make you laugh. Deal Me In humanizes the larger-than-life personalities, allowing the reader to understand more about poker strategy through the trials and errors of the best players in the game. Each poker legend tells his or her own story in the book including: Doyle Brunson, Phil Hellmuth , Daniel Negreanu, Phil Ivey, Annie Duke, Johnny Chan, Chris Jesus Ferguson, Carlos Mortensen, Chau Giang, Jennifer Harman, Allen Cunningham, Howard Lederer, Erik Seidel, Chad Brown, David Devilfish Ulliott, Layne Flack, Scotty Nguyen, Annette Obrestad, Tom Dwan and the 2008 Main Event winner Peter Eastgate. -

Multi-Accounter Jjprodigy Wieder Aufgeflogen Und Noch Mehr Klatsch & Tratsch Aus Der Poker Szene

Multi-Accounter JJProdigy wieder aufgeflogen und noch mehr Klatsch & Tratsch aus der Poker Szene Von Lilly Wolf Klatsch und Tratsch Josh Field, aka JJProdigy, wurde vom Online Pokerroom Cake Poker gesperrt, nachdem ihm schon wieder Multi-Accounting nachgewiesen wurde. Field, der schon in mehreren Multi-Accounting Skandale verwickelt war, scheint es nicht lassen zu können. Auf vielen Online-Seiten wurde sein Account bereits gesperrt, nun auch bei Cake Poker. Field erstellte den Namen OnThatGrind und ließ Spieler, die er stakte unter diesem Namen High Limit Games spielen. Das Sicherheitsteam von Cake Poker hatte wegen seiner Vergangenheit bereits ein Auge auf ihn geworfen und reagierte prompt. Wieder ein Pokerroom weniger für JJProdigy. Zum Glück gibt es ja immer wieder neue. Tom Dwan und Phil Ivey auf Full Tilt Poker Tom Dwan und Phil Ivey scheinen sich schon für die Million Dollar Challenge warm zu spielen, denn die beiden spielten auf FullTilt Poker auf Ivey Mix und Ivey Thunderdome. Ivey Mix ist ein halb PLO – halb PL Holdem Tisch. Tom Dwan ging auf Ivey Mix schon früh in Führung und Ivey ging mit USD 40.000 und K-J All-In. Dwan callte mit A-Q und holte sich bei einem Board mit J-3-9-A-2 den Pot. Ivey kaufte sich für weitere USD 100,000 ein, von denen er die Hälfte ebenfalls nach kurzer Zeit an Dwan verlor. Dann wendete sich das Blatt für Ivey: Die teuerste Hand der Session lief auf Ivey Mix. Bei einem Board von 10-3-4-10-Q ging Ivey mit USD 126,685 All-In und Dwan callte mit A-10. -

GOING ALL-IN on the AMERICAN DREAM: MYTH, RHETORIC, and the POKERIZATION of AMERICA Aaron M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Communication Studies, Department of Student Research 4-20-2011 GOING ALL-IN ON THE AMERICAN DREAM: MYTH, RHETORIC, AND THE POKERIZATION OF AMERICA Aaron M. Duncan University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Duncan, Aaron M., "GOING ALL-IN ON THE AMERICAN DREAM: MYTH, RHETORIC, AND THE POKERIZATION OF AMERICA" (2011). Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research. Paper 8. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstuddiss/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Studies Theses, Dissertations, and Student Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING ALL-IN ON THE AMERICAN DREAM: MYTH, RHETORIC, AND THE POKERIZATION OF AMERICA by Aaron Michael Duncan A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Communication Studies Under the Supervision of Professor Ronald Lee Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2011 GOING ALL IN ON THE AMERICAN DREAM: REHTORIC, MYTH, AND THE POKERIZATION OF AMERICA Aaron Michael Duncan, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2011 Adviser: Ronald Lee This dissertation takes a rhetorical approach in exploring the rise of gambling in America, and in particular the growth of the game of poker, as a means to explore larger changes to America‘s collective consciousness. I argue that the collective American conscious has undergone dramatic changes in recent years and an increased acceptance of gambling is reflective of these changes.