Memory, Trauma and Ethics in Ari Folman's Waltz with Bashir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special Programs 215 345 6789

County Theater 79 PreviewsMARCH – MAY 2012 DAMSELS IN DISTRESS DAMSELS INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTY T HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. How can you support ADMISSION COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER General ..............................................................$9.75 Be a member. Members ...........................................................$5.00 Become a member of the nonprofit County Theater and Seniors (62+) show your support for good Students (w/ID) & Children (<18). ..................$7.25 films and a cultural landmark. See back panel for a member- Matinees ship form or join on-line. Your financial support is tax-deductible. Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 Make a gift. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .......................................$7.25 Your additional gifts and support make us even better. Your Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ..........................$5.00 donations are fully tax-deductible. And you can even put your Affiliated Theaters Members* .............................$6.00 name on a bronze star in the sidewalk! You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. Contact our Business Office at (215) 348-1878 x117 or at The above ticket prices are subject to change. [email protected]. Be a sponsor. *Affiliated Theaters Members Receive prominent recognition for your business in exchange The County Theater, the Ambler Theater, and the Bryn Mawr Film for helping our nonprofit theater. Recognition comes in a variety Institute have reciprocal admission benefits. Your membership will of ways – on our movie screens, in our brochures, and on our allow you $6.00 admission at the other theaters. -

Export Statt Exodus

Bild nur in Printausgabe verfügbar Export statt Exodus Winfried Schumacher | Kleines Land mit großer Kultur: Israels Künstler, Autoren und Filmemacher sind weltweit gefragt. Mit Verve, Chuzpe und Selbst ironie widmen sie sich dem komplizierten Leben in einem von Krieg, Terror und politischen Grabenkämpfen gebeutelten Land. Die Schroffheit und Verletzlichkeit ihrer Alltagshelden kommt auch im Ausland an. Sie feilen an ihren Fingernägeln, kochen Kaffee für den Vorgesetzten, schred- dern nie gelesene Akten und räumen Minenfelder höchstens auf Minesweeper. Die Uniformen der Soldatinnen sitzen schlecht und ihre Knarren sind nichts als lästige Accessoires. Was die israelische Regisseurin Talya Lavie in ihrem Filmdebüt „Zero Motivation“ zeigt, ist gähnende Langeweile in einer Militär- basis. Und doch sorgte die schwarze Komödie in Israel für einen der größten Kinoerfolge der vergangenen Jahre. Keine Kassam-Raketen, keine Konfliktanalysen und schon gar keine Kriegshelden sind in „Zero Motivation“ zu sehen. Mit bösem Witz und mes- serscharfem Blick auf den öden Alltag im Lager beobachtet Lavie das Leben einer Gruppe von Soldatinnen in der Negev-Wüste. Sie zählen die Tage bis 58 IP Länderporträt • 2 / 2016 Export statt Exodus zum Ende ihres Militärdiensts und träumen vom Partyleben in Tel Aviv. Der glorreiche Einsatz für das Land der Väter bedeutet für sie nur das Absitzen von Dienstanweisungen lächerlicher Rangoberer. Wer kein Hebräisch spricht und nie eine israelische Militärbasis von innen gesehen hat – erst recht, wer noch nie in Israel war – wird den Humor eines großen Teiles der Dialoge auch mit englischen Untertiteln nicht ganz verste- hen. Zu vielschichtig und kulturspezifisch ist der Schlagabtausch. Dennoch wurde der Film auf dem Tribeca Film Festival als bester Film ausgezeichnet und erregte das Interesse von BBC America. -

Course Description Fall 2013

COURSE DESCRIPTION FALL 2013 TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL STUDY ABROAD ‐ FALL SEMESTER 2013 COURSE DESCRIPTION MAIN OFFICE UNITED STATES CANADA The Carter Building , Room 108 Office of Academic Affairs Lawrence Plaza Ramat Aviv, 6997801, Israel 39 Broadway, Suite 1510 3130 Bathurst Street, Suite 214 Phone: +972‐3‐6408118 New York, NY 10006 Toronto, Ontario M6A 2A1 Fax: +972‐3‐6409582 Phone: +1‐212‐742‐9030 [email protected] [email protected] Fax: +1‐212‐742‐9031 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL.TAU.AC.IL 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ■ FALL SEMESTER 2013 DATES 3‐4 ■ ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS 6‐17 O INSTRUCTIONS FOR REGISTRATION 6‐7 O REGULAR UNIVERSITY COURSES 7 O WITHDRAWAL FROM COURSES 8 O PASS/FAIL OPTION 8 O INCOMPLETE COURSES 8 O GRADING SYSTEM 9 O CODE OF HONOR AND ACADEMIC INTEGRITY 9 O RIGHT TO APPEAL 10 O SPECIAL ACCOMMODATIONS 10 O HEBREW ULPAN REGULATIONS 11 O TAU WRITING CENTER 11‐12 O DESCRIPTION OF LIBRARIES 13 O MOODLE 13 O SCHEDULE OF COURSES 14‐16 O EXAM TIMETABLE 17 ■ TRANSCRIPT REQUEST INSTRUCTIONS 18 ■ COURSE DESCRIPTIONS 19‐97 ■ REGISTRATION FORM FOR STUDY ABROAD COURSES 98 ■ EXTERNAL REGISTRATION FORM 99 2 FALL SEMESTER 2013 IMPORTANT DATES ■ The Fall Semester starts on Sunday, October 6th 2013 and ends on Thursday, December 19th 2013. ■ Course registration deadline: Thursday, September 8th 2013. ■ Class changes and finalizing schedule (see hereunder): October 13th – 14th 2013. ■ Last day in the dorms: Sunday, December 22nd 2013. Students are advised to register to more than the required 5 courses but not more than 7 courses. -

Dear Mr. Waldman Press Kit Aug08

DEARDEAR MR.MR. WALDMANWALDMAN Michtavim le America A FEATURE FILM BY HANAN PELED Awards: 3 NOMINATIONS Israeli Academy Awards Including Best Actor AUDIENCE AWARD, Reheboth Beach Independent Film Festival Selected Festival Screenings: Jerusalem International Film Festival UK Jewish Film Festival Palm Springs International Film Festival Munich Film Festival Atlanta Jewish Film Festival – Closing Night Film Washington DC Jewish Film Festival Palm Beach Jewish Film Festival Vancouver Jewish Film Festival Chicago Festival of Israeli Cinema San Diego Jewish Film Festival Sacramento Jewish Film Festival Denver Jewish Film Festival Israel Nonstop, NYC Distributed in North America by: The National Center for Jewish Film Brandeis University Lown 102, MS 053 Waltham, MA 02454 (781) 736-8600 [email protected] www.jewishfilm.org AN OPEN DOORS FILMS/TMUNA COMMUNICATIONS DEAR MR. WALDMAN It is the early 1960s in Tel Aviv and ten-year-old Hilik knows his goal in life – to make his parents happy and compensate for the grief they both suffered in the Holocaust. The fragile equilibrium of the new life Rivka and Moishe have forged for themselves and their sons, Hilik and Yonatan, in the new state of Israel begins to waver when Moishe convinces himself that Yankele, his son from his first marriage, didn't actually die in Auschwitz, but rather miraculously escaped to America, where he grew to adulthood and became an advisor to President John Kennedy. Moishe never really accepted the fact that he alone survived the Holocaust, and after seeing “Jack Waldman’s” picture in the newspaper, he finds himself sinking into his past. When Moishe writes a letter to Waldman, Hilik takes matters into his own hands. -

Israeli Film Fest Returns Jan. 16, 23 Interfaith Panel at TI to Examine

January 2010 NoFebruaryvember 20062007 Tevet/Shevat 5770 Heshvan/KisleShevat/Adar v 5767 5767 2200 Baltimore Road •• Rockville, Rockville, Maryland Maryland 20850 20851 www.tikvatisrael.org VolumeVolume 41 •• NumberNumber 1 It’sFrom Show the Time!President’ Israelis FilmPerspective Fest Returns Jan. 16, 23 Weekly Religious Services Weekly Religious Services The.annual.Israeli.Film.Festival.at.Tikvat.Israel.will.feature.a.pair.of.movies.created.by. This new and handsome bulletin format that we will succeed more than we will Joseph.Cedar,.a.decorated.Israeli.film.director. Monday..........6:45.a.m........... 7:30.p.m. is a fortuitous metaphor for the many changes fail. We will witness the vibrant growth of Monday ....... 6:45 a.m. ........ 7:30 p.m. The.two.screenings.are.“Time.of.Favor”.on.Jan..16.and.“Campfire”.on.Jan..23..Both. Tuesday.................................. 7:30.p.m. that Tikvat Israel Congregation will be our community that some don’t expect, but films.will.begin.at.7:45.p.m..Tickets.are.$10.per.film.for.a.TI.member,.$12.for.a.non- Tuesday ................................. 7:30 p.m. experiencing this year. Rori Pollak will be that we all want. This has been my philosophy Wednesday............................. 7:30.p.m. [email protected]. joining us in June as new director of the and approach towards my own career as a ThursdayWednesday....................................6:45.a.m........... 7:307:30. p.m. Cedar.received.international.attention.with.the.release.of.his.2007.film.“Beaufort”. Broadman-Kaplan Early Childhood Center. scientist, co-chair of the AEC, and now as Friday.............6:45.a.m.......................... -

Communication 140 Introduction to Film Studies

COMMUNICATION 140 INTRODUCTION TO FILM STUDIES Waltz With Bashir [Vals Im Bashir] (2008) Written and directed by Ari Folman. Edited by Nili Feller. Music by Max Richter. With the voicework of Ari Folman, Ori Sivan, Ronny Dayag, Shmuel Frenkel, Zahava Solomon, Ron Ben-Yishai, and Dror Harazi. Ari Folman’s broodingly original Waltz With Bashir—one of the highlights of the last New York Film Festival—is a documentary that seems only possible, not to mention bearable, as an animated feature. Folman, whose magic realist youth film Saint Clara was one of the outstanding Israeli films of the 1990s, has created a grim, deeply personal phantasmagoria around the 1982 invasion of Lebanon. Waltz With Bashir, named for Bashir Gemayel, the charismatic hero of the Christian militias that allied themselves with Israel, is an illustrated oral history based on interviews that Folman conducted with former comrades, which mixes dreams with their incomplete or conflicting recollections. Waltz With Bashir opens with a pack of slavering dogs rampaging through nocturnal Tel Aviv—the dramatization of a recurring nightmare experienced by one of Folman’s friends. His assignment, when entering a Lebanese village, had been to silence the dogs because “they knew I couldn’t shoot a person.” One dream triggers another: Folman, who claims to have forgotten everything about his wartime experiences, has his sleep disturbed by a vision of soldiers, naked save for their dog tags and Uzis, drifting zombie-like out of the ocean onto Beirut’s posh hotel strip. That which has been repressed returns with startling ferocity. Although it can be highly explicit in detailing war’s horror, Waltz With Bashir is mainly concerned with the recollection of trauma. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: the Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-3-2007 Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films ot Facilitate Dialogue Elana Shefrin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Shefrin, Elana, "Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-MEDIATING THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: THE USE OF FILMS TO FACILITATE DIALOGUE by ELANA SHEFRIN Under the Direction of M. Lane Bruner ABSTRACT With the objective of outlining a decision-making process for the selection, evaluation, and application of films for invigorating Palestinian-Israeli dialogue encounters, this project researches, collates, and weaves together the historico-political narratives of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, the artistic worldviews of the Israeli and Palestinian national cinemas, and the procedural designs of successful Track II dialogue interventions. Using a tailored version of Lucien Goldman’s method of homologic textual analysis, three Palestinian and three Israeli popular film texts are analyzed along the dimensions of Historico-Political Contextuality, Socio- Cultural Intertextuality, and Ethno-National Textuality. Then, applying the six “best practices” criteria gleaned from thriving dialogue programs, coupled with the six “cautionary tales” criteria gleaned from flawed dialogue models, three bi-national peacebuilding film texts are homologically analyzed and contrasted with the six popular film texts. -

Association for Jewish Studies

42ND ANNUAL CONFERENCE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES DECEMBER 19– 21, 2010 WESTIN COPLEY PLACE BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES C/O CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY 15 WEST 16TH STREET NEW YORK, NY 10011-6301 PHONE: (917) 606-8249 FAX: (917) 606-8222 E-MAIL: [email protected] www.ajsnet.org President AJS Staff Marsha Rozenblit, University of Maryland Rona Sheramy, Executive Director Vice President/Membership Karen Terry, Program and Membership and Outreach Coordinator Anita Norich, University of Michigan Natasha Perlis, Project Manager Vice President/Program Emma Barker, Conference and Program Derek Penslar, University of Toronto Associate Vice President/Publications Karin Kugel, Program Book Designer and Jeffrey Shandler, Rutgers University Webmaster Secretary/Treasurer Graphic Designer, Cover Jonathan Sarna, Brandeis University Ellen Nygaard The Association for Jewish Studies is a Constituent Society of The American Council of Learned Societies. The Association for Jewish Studies wishes to thank the Center for Jewish History and its constituent organizations—the American Jewish Historical Society, the American Sephardi Federation, the Leo Baeck Institute, the Yeshiva University Museum, and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research— for providing the AJS with offi ce space at the Center for Jewish History. Cover credit: “Israelitish Synagogue, Warren Street,” in the Boston Almanac, 1854. American Jewish Historical Society, Boston, MA and New York, NY. Copyright © 2010 No portion of this publication may be reproduced by any means without the express written permission of the Association for Jewish Studies. The views expressed in advertisements herein are those of the advertisers and do not necessarily refl ect those of the Association for Jewish Studies. -

Pressed Minority, in the Diaspora

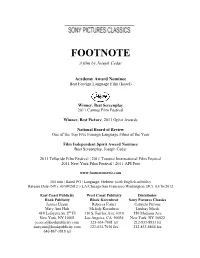

FOOTNOTE A film by Joseph Cedar Academy Award Nominee Best Foreign Language Film (Israel) Winner, Best Screenplay 2011 Cannes Film Festival Winner, Best Picture, 2011 Ophir Awards National Board of Review One of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of the Year Film Independent Spirit Award Nominee Best Screenplay, Joseph Cedar 2011 Telluride Film Festival | 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 New York Film Festival | 2011 AFI Fest www.footnotemovie.com 105 min | Rated PG | Language: Hebrew (with English subtitles) Release Date (NY): 03/09/2012 | (LA/Chicago/San Francisco/Washington, DC): 03/16/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS FOOTNOTE is the tale of a great rivalry between a father and son. Eliezer and Uriel Shkolnik are both eccentric professors, who have dedicated their lives to their work in Talmudic Studies. The father, Eliezer, is a stubborn purist who fears the establishment and has never been recognized for his work. Meanwhile his son, Uriel, is an up-and-coming star in the field, who appears to feed on accolades, endlessly seeking recognition. Then one day, the tables turn. When Eliezer learns that he is to be awarded the Israel Prize, the most valuable honor for scholarship in the country, his vanity and desperate need for validation are exposed. -

181 Chapter Five Back to the Army

Chapter Five Back to the Army: the Privatization of the War Experience as David vs David 181 182 5.1 From the Second Intifada to the Wars of the New Millennium “In the second Intifada, we, Jews and Palestinians, reverted to primal warfare: rocks, knives, vendettas, an eye for an eye, blood and soil, dismembered bodies. Israeli called it “the situation”. […] A kind of frozen time. […] The distinction between home and battlefield melted away. The entire country was the front line” (Boaz Neummann, 2010, pag. X-XI). The New Millennium, the end of Hegemony and the Onset of Cultural Plurality “Thirty years later, today’s army, the senior officers who remain from those days, and the same politicians who were involved in the war then are still trying to keep the public in the dark. The truth, nonetheless, is gradually being revealed” (Ashkenazi, 2003). As Kimmerling argues accurately in his work “The Invention and Decline of Israeliness,” alongside the already existing cleavage between Jews and Palestinians, the conquest of territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in the 1967 war gradually introduced another major sociopolitical fall into the system: “‘Holy sites’ out of the Israeli state’s control since the 1948 war were once again in Jewish hands, raising strong religious (often messianic) sentiments among the Israeli secular and religious Jewish population. This overwhelming victory, after a long and traumatic period of waiting, was frequently presented in terms of divine intervention in Jewish history, the antithesis of the Holocaust and continuation of the “miraculous” victory in the 1948 war and the establishment of a Jewish sovereign state” (Kimmerling, 2001, p.113). -

Waltz with Bashir

waltzBPressbook-SPCRevise_081108_FNL:Layout 1 8/11/08 2:38 PM Page 1 WALTZ WITH BASHIR AN ARI FOLMAN FILM waltzBPressbook-SPCRevise_081108_FNL:Layout 1 8/11/08 2:38 PM Page 2 waltzBPressbook-SPCRevise_081108_FNL:Layout 1 8/11/08 2:38 PM Page 3 SYNOPSIS One night at a bar, an old friend tells director Ari about a recurring nightmare in which he is chased by 26 vicious dogs. Every night, the same number of beasts. The two men conclude that there’s a connection to their Israeli Army mission in the first Lebanon War of the early eighties. Ari is surprised that he can’t remember a thing anymore about that period of his life. Intrigued by this riddle, he decides to meet and interview old friends and comrades around the world. He needs to discover the truth about that time and about himself. As Ari delves deeper and deeper into the mystery, his memory begins to creep up in surreal images … waltzBPressbook-SPCRevise_081108_FNL:Layout 1 8/11/08 2:38 PM Page 4 INTERVIEW WITH ARI FOLMAN Did you start this project as an animated documentary? Yes indeed. WALTZ WITH BASHIR was always meant to be an animated documentary. For a few years, I had the basic idea for the film in my mind but I was not happy at all to do it in real life video. How would that have looked like? A middleaged man being interviewed against a black background, telling stories that happened 25 years ago, without any archival footage to support them. That would have been SO BORING! Then I figured out it could be done only in animation with fantastic drawings.