Conflict and Environment in North Lebanon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Cement Competition 2019

1. Introduction 1.1. Overview 1.2. Chekka and the Collar Towns: Understanding the Challenges 1.3. The Competition: Open Call for Alternative Visions ● Competition Guidelines ● Goals of the Competition 2. Three Sites, One Vision 2.1. Ruptures and Continuities: Relations Between the Sites 2.2. Site A: Chekka-Heri Seafront ● Understanding the Site ● Current Problematic ● Stakeholders 2.3. Site B: Badbhoun’s Quarry ● Understanding the Site ● Current Problematic ● Stakeholders 2.4. Site C: Koura’s Agricultural Middle Plain ● Understanding the Site ● Current Problematic ● Stakeholders 3. Competition Requirements and Conditions 3.1. Structure and Jury Deliberation 3.1.1. Competition Organizer and Supporters 3.1.2. Competition Type 3.1.3. Eligibility 3.1.4. Jury Panel 3.1.5. Award 3.1.6. Evaluation Criteria 3.1.7. Timeline 3.2. Submission Requirements 3.2.1. List of Required Deliverables 3.2.2. Further Instructions 3.3. Terms and Conditions 3.3.1. Official Language 3.3.2. Anonymity 3.3.3. Communication 3.3.4. Confidentiality Beyond Cement Competition 2019 3.3.5. Ownership of Entries 3.3.6. Authorship and Originality of Entries 3.3.7. Exhibition, Publication, and Promotion 3.3.8. Submission of Entries Deadlines 3.3.9. Changes to the Competition 3.3.10. Handling of Deliverables 3.3.11. Indemnity Clause Appendices In addition to the appendices referenced in the text above, The following includes other materials that participants are encouraged to go through as they provide important information relevant to the specific sites and the competition as a whole. 1. Maps 1.1 Base maps 1.2 Master plans 1.3 Mapping 1.4 Graphs 2. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99q9f2k0 Author Bailony, Reem Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Reem Bailony 2015 © Copyright by Reem Bailony 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 by Reem Bailony Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor James L. Gelvin, Chair This dissertation explores the transnational dimensions of the Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927. By including the activities of Syrian migrants in Egypt, Europe and the Americas, this study moves away from state-centric histories of the anti-French rebellion. Though they lived far away from the battlefields of Syria and Lebanon, migrants championed, contested, debated, and imagined the rebellion from all corners of the mahjar (or diaspora). Skeptics and supporters organized petition campaigns, solicited financial aid for rebels and civilians alike, and partook in various meetings and conferences abroad. Syrians abroad also clandestinely coordinated with rebel leaders for the transfer of weapons and funds, as well as offered strategic advice based on the political climates in Paris and Geneva. Moreover, key émigré figures played a significant role in defining the revolt, determining its goals, and formulating its program. By situating the revolt in the broader internationalism of the 1920s, this study brings to life the hitherto neglected role migrants played in bridging the local and global, the national and international. -

The Haifa–Beirut–Tripoli Railway

APPENDIX 2 THE HAIFA–BEIRUT–TRIPOLI RAILWA Y By A. E. FIEL D Syria does not lend itself easily to railway construction . Very little such work was undertaken between the two world wars. In 1940, however, the possibility of Allied occupation of the Lebanon, and the hope that Turke y would join the Allies, made it very desirable that there should be a direct link between the standard gauge line from the British bases i n Egypt and Palestine then terminating at Haifa, and the northern Syrian system ending at Tripoli . Earlier the French administration had considered the linking of Haifa and Tripoli by a route along the coast, but the project had been shelved for fear that the port of Haifa would benefit at the expense of Beirut. In 1940 and 1941 Middle East Command had surveys made of various routes as far as the Lebanon border . From a map study the first route favoured was from Haifa round the north o f the Sea of Galilee to Rayak where the proposed railway would join th e Homs-Aleppo-Turkey standard gauge line . This was ruled out because it involved very heavy cutting in basalt . The next possibility considered was an extension of the line northwards from Haifa along the coast to th e Litani River and thence inland to Metulla-Rayak, but the route could not be explored before the conquest of Syria in July 1941 . It then became evident that much heavy bridge work would be necessary in the Litani gorges which would not be economically justifiable as a wartime project . -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Usaid/Lebanon Lebanon Industry Value Chain

USAID/LEBANON LEBANON INDUSTRY VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT (LIVCD) PROJECT LIVCD QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT - YEAR 3, QUARTER 4 JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2015 FEBRUARY 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. CONTENTS ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................3 YEAR 3 QUARTER 4: JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30 2015 ............................................................... 4 PROJECT OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 4 EXCUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................... 4 QUARTERLY REPORT structure ...................................................................................................................... 5 1. LIVCD YEAR 3 QUARTER 4: RESULTS (RESULTS FRAMEWORK & PERFORMANCE INDICATORS) ................................................................................................................................6 Figure 1: LIVCD Results framework and performance indicators ......................................................... 7 Figure 2: Results achieved against targets .................................................................................................... 8 Table 1: Notes on results achieved .................................................................................................................. -

Baalbek Hermel Zahleh Jbayl Aakar Koura Metn Batroun West Bekaa Zgharta Kesrouane Rachaiya Miniyeh-Danniyeh Bcharreh Baabda Aale

305 307308 Borhaniya - Rehwaniyeh Borj el Aarab HakourMazraatKarm el Aasfourel Ghatas Sbagha Shaqdouf Aakkar 309 El Aayoun Fadeliyeh Hamediyeh Zouq el Hosniye Jebrayel old Tekrit New Tekrit 332ZouqDeir El DalloumMqachrine Ilat Ain Yaaqoub Aakkar El Aatqa Er Rouaime Moh El Aabdé Dahr Aayas El Qantara Tikrit Beit Daoud El Aabde 326 Zouq el Hbalsa Ein Elsafa - Akum Mseitbeh 302 306310 Zouk Haddara Bezbina Wadi Hanna Saqraja - Ein Eltannur 303 Mar Touma Bqerzla Boustane Aartoussi 317 347 Western Zeita Al-Qusayr Nahr El Bared El318 Mahammara Rahbe Sawadiya Kalidiyeh Bhannine 316 El Khirbe El Houaich Memnaa 336 Bebnine Ouadi Ej jamous Majdala Tashea Qloud ElEl Baqie Mbar kiye Mrah Ech Chaab A a k a r Hmaire Haouchariye 34°30'0"N 338 Qanafez 337 Hariqa Abu Juri BEKKA INFORMALEr Rihaniye TENTEDBaddouaa El Hmaira SETTLEMENTS Bajaa Saissouq Jouar El Hachich En Nabi Kzaiber Mrah esh Shmis Mazraat Et Talle Qarqaf Berkayel Masriyeh Hamam El Minié Er Raouda Chane Mrah El Dalil Qasr El Minie El Kroum El Qraiyat Beit es Semmaqa Mrah Ez Zakbe Diyabiyeh Dinbou El Qorne Fnaydek Mrah el Arab Al Quasir 341 Beit el Haouch Berqayel Khraibe Fnaideq Fissane 339 Beit Ayoub El Minieh - Plot 256 Bzal Mishmish Hosh Morshed Samaan 340 Aayoun El Ghezlane Mrah El Ain Salhat El Ma 343 Beit Younes En Nabi Khaled Shayahat Ech Cheikh Maarouf Habchit Kouakh El Minieh - Plots: 1797 1796 1798 1799 Jdeidet El Qaitaa Khirbit Ej Jord En Nabi Youchaa Souaisse 342 Sfainet el Qaitaa Jawz Karm El Akhras Haouch Es Saiyad AaliHosh Elsayed Ali Deir Aamar Hrar Aalaiqa Mrah Qamar ed Dine -

Copyright© 2017 Mediterranean Marine Science

Mediterranean Marine Science Vol. 18, 2017 Introduced marine macroflora of Lebanon and its distribution on the Levantine coast BITAR G. Lebanese University, Faculty of Sciences, Hadaeth, Beirut, Lebanon RAMOS-ESPLÁ A. Centro de Investigación Marina de Santa Pola (CIMAR), Universidad de Alicante, 03080 Alicante OCAÑA O. Departamento de Oceanografía Biológica y Biodiversidad, Fundación Museo del Mar, Muelle Cañonero Dato s.n, 51001 Ceuta SGHAIER Y. Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas (RAC/SPA) FORCADA A. Departamento de Ciencias del Mar y Biología Aplicada, Universidad de Alicante, Po Box 99, Edificio Ciencias V, Campus de San Vicente del Raspeig, E-03080, Alicante VALLE C. Departamento de Ciencias del Mar y Biología Aplicada, Universidad de Alicante, Po Box 99, Edificio Ciencias V, Campus de San Vicente del Raspeig, E-03080, Alicante EL SHAER H. IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), Regional Office for West Asia Sweifiyeh, Hasan Baker Al Azazi St. no 20 - Amman VERLAQUE M. Aix Marseille University, CNRS/INSU, Université de Toulon, IRD, Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography (MIO), UM 110, GIS Posidonie, 13288 Marseille http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.1993 Copyright © 2017 Mediterranean Marine Science http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 04/08/2019 04:30:09 | To cite this article: BITAR, G., RAMOS-ESPLÁ, A., OCAÑA, O., SGHAIER, Y., FORCADA, A., VALLE, C., EL SHAER, H., & VERLAQUE, M. (2017). Introduced marine macroflora of Lebanon and its distribution on the Levantine coast. Mediterranean Marine Science, 18(1), 138-155. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.1993 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 04/08/2019 04:30:09 | Review Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.1993 The introduced marine macroflora of Lebanon and its distribution on the Levantine coast G. -

II. Existing Tourism Assets in Rachaya

1 I. Objectives and scope of the study VNG International, with its headquarters based in The Hague, in assignment of the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, aims at strengthening resilience of local governments Lebanon in order to be able to improve living conditions of local populations and Syrian refugees in their host communities. For the Local Government Resilience Programme (LOGOReP) VNG International will collaborate with Dutch, as well as Jordanian and Lebanese (unions of) municipalities, with the UNDP & UNHCR, and NGOs operating in the targeted areas. Within the Local Government Resilience Programme (LOGOReP) Lebanon project, VNGI and its municipal partners work on the development of local economies and municipal service provision within the context of the refugee crisis, more specifically in the West- Beqaa region. The aim of the Urban Planning and Local Economic Development (LED) in the LOGOReP is to offer tools for integrated economic and spatial development on the long term at the scale of a regional urbanized area : Rachaya, located in the Bekaa Valley. Ownership of the SEDP will be transferred to Rachaya Union and Rachaya village, source: unknown author Rachaya Municipality after its final delivery and these parties will have to use the SEDP twofold: - As their local spatial strategy; - As a blueprint for discussions with potential investing or financing parties. 2 I. Localization II. Governance III. Brief History IV. Climate V. Archeology 3 I. Localization Rachaya El- Wadi is the capital of the Caza of Rachaya. It is a small town seated on the western slopes of Mount Hermon. It is located in the South Beqaa at 85 kilometers from Beirut, in the northern side of the Wadi el Taym valley. -

5 Million M2: When Will the State Recover Them?

issue number 158 |September 2015 SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT IN LEBANON HEFTY COST AND UNSOLVED CRISIS POSTPONING THE RELEASE OF LEBANON’S ARMY COMMANDER THE MONTHLY INTERVIEWS NABIL ZANTOUT www.monthlymagazine.com Published by Information International sal GENERAL MANAGER AT IBC USURPATION OF COASTAL PUBLIC PROPERTY 5 MILLION M2: WHEN WILL THE STATE RECOVER THEM? Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros September INDEX 2015 4 USURPATION OF COASTAL PUBLIC PROPERTY 5 MILLION M2: WHEN WILL THE STATE RECOVER THEM? 16 2013 CENTRAL INSPECTION REPORT 19 SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT IN LEBANON HEFTY COST AND UNSOLVED CRISIS 22 POSTPONING THE RELEASE OF LEBANON’S ARMY COMMANDER 24 JAL EL-DIB: BETWEEN THE TUNNEL AND THE BRIDGE 25 PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN: QONUNCHILIK PALATASI P: 28 P: 16 26 RASHID BAYDOUN (1889-1971) 28 INTERVIEW: NABIL ZANTOUT GENERAL MANAGER AT IBC 31 INJAZ LEBANON 33 POPULAR CULTURE 34 DEBUNKING MYTH#97: SHOULD WE BRUSH OUR TEETH IMMEDIATELY AFTER EATING? 35 MUST-READ BOOKS: DAR SADER- IN BEIRUT... A THOUGHT SPARKED UP 36 MUST-READ CHILDREN’S BOOK: THE BANANA P: 19 37 LEBANON FAMILIES: QARQOUTI FAMILIES 38 DISCOVER LEBANON: SMAR JBEIL 39 DISCOVER THE WORLD: NAURU 40 JULY 2015 HIGHLIGHTS 49 REAL ESTATE PRICES - JULY 2015 44 THIS MONTH IN HISTORY- LEBANON 50 DID YOU KNOW THAT?: 2014 FIFA WORLD CIVIL WAR DIARIES CUP THE ZGHARTA-TRIPOLI FRONT 40 YEARS AGO 50 RAFIC HARIRI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT 47 THIS MONTH IN HISTORY- ARAB WORLD - JORDAN TRAFFIC - JULY 2015 BLACK SEPTEMBER EVENTS 51 LEBANON’S STATS 48 TERRORIST GROUPS PRETENDING TO STAND FOR ISLAM (8) ANSAR AL-SHARIA’A: ORIGINATING FROM LIBYA AND ESPOUSING ISLAMIC SHARIA’A |EDITORIAL Iskandar Riachi Below are excerpts from chapter 40 of Iskandar Riachi’s book Before and After, which was published in Lebanon in the 1950s. -

Layout CAZA AAKAR.Indd

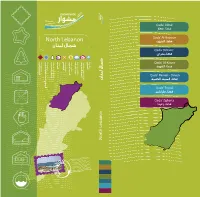

Qada’ Akkar North Lebanon Qada’ Al-Batroun Qada’ Bcharre Monuments Recreation Hotels Restaurants Handicrafts Bed & Breakfast Furnished Apartments Natural Attractions Beaches Qada’ Al-Koura Qada’ Minieh - Dinieh Qada’ Tripoli Qada’ Zgharta North Lebanon Table of Contents äÉjƒàëªdG Qada’ Akkar 1 QɵY AÉ°†b Map 2 á£jôîdG A’aidamoun 4-27 ¿ƒeó«Y Al-Bireh 5-27 √ô«ÑdG Al-Sahleh 6-27 á∏¡°ùdG A’andaqet 7-28 â≤æY A’arqa 8-28 ÉbôY Danbo 9-29 ƒÑfO Deir Jenine 10-29 ø«æL ôjO Fnaideq 11-29 ¥ó«æa Haizouq 12-30 ¥hõ«M Kfarnoun 13-30 ¿ƒfôØc Mounjez 14-31 õéæe Qounia 15-31 É«æb Akroum 15-32 ΩhôcCG Al-Daghli 16-32 »∏ZódG Sheikh Znad 17-33 OÉfR ï«°T Al-Qoubayat 18-33 äÉ«Ñ≤dG Qlaya’at 19-34 äÉ©«∏b Berqayel 20-34 πjÉbôH Halba 21-35 ÉÑ∏M Rahbeh 22-35 ¬ÑMQ Zouk Hadara 23-36 √QGóM ¥hR Sheikh Taba 24-36 ÉHÉW ï«°T Akkar Al-A’atiqa 25-37 á≤«à©dG QɵY Minyara 26-37 √QÉ«æe Qada’ Al-Batroun 69 ¿hôàÑdG AÉ°†b Map 40 á£jôîdG Kouba 42-66 ÉHƒc Bajdarfel 43-66 πaQóéH Wajh Al-Hajar 44-67 ôéëdG ¬Lh Hamat 45-67 äÉeÉM Bcha’aleh 56-68 ¬∏©°ûH Kour (or Kour Al-Jundi) 47-69 (…óæédG Qƒc hCG) Qƒc Sghar 48-69 Qɨ°U Mar Mama 49-70 ÉeÉe QÉe Racha 50-70 É°TGQ Kfifan 51-70 ¿ÉØ«Øc Jran 52-71 ¿GôL Ram 53-72 ΩGQ Smar Jbeil 54-72 π«ÑL Qɪ°S Rachana 55-73 ÉfÉ°TGQ Kfar Helda 56-74 Gó∏MôØc Kfour Al-Arabi 57-74 »Hô©dG QƒØc Hardine 58-75 øjOôM Ras Nhash 59-75 ¢TÉëf ¢SGQ Al-Batroun 60-76 ¿hôàÑdG Tannourine 62-78 øjQƒæJ Douma 64-77 ÉehO Assia 65-79 É«°UCG Qada’ Bcharre 81 …ô°ûH AÉ°†b Map 82 á£jôîdG Beqa’a Kafra 84-97 GôØc ´É≤H Hasroun 85-98 ¿hô°üM Bcharre 86-97 …ô°ûH Al-Diman 88-99 ¿ÉªjódG Hadath -

Annual Project Work Plan

Project Code & Title:UNDP ART GOLD-BEKAA FORM No...... Responsible Officer: ………………………….......................... Implementing Partner: ……………………............................. ANNUAL PROJECT PROGRESS REPORT Period: 01 – 12/ 2010 MAJOR PLANNED ACTIVITIES ACTUAL ACHIEVEMENTS, PROGRESS AGAINST PENDING ISSUES/ REASONS FOR EXPECTED PROJECT OUTPUTS & List major activities, including M&E OUTPUTS, INDICATORS & ANNUAL TARGETS ADJUSTMENTS INDICATORS activities , to be undertaken during the year (Including annual targets) in order to produce the stated project outputs 1- Green coverage improved in 1.1 Establish a forestry Nursery in 2 regions A Nursery established in Nabi Shiit – Baalbeck: The main constrain for the execution of the Bekaa in Nabi Shiit –Baalbek and Kefraya – West Direct beneficiaries: 12,000 & Indirect proposed project in Kefraya was the budget -two nurseries established in Bekaa beneficiaries: 7 municipalities (Population of delay. Implementation will start first quarter Baalbek region that produces 1.1.1 2. Procure trees, seeds, pesticides and Baalbeck eastern federation (35,000 persons). of 2011 and continues through the year. 100,000 forest trees seedlings in agricultural equipment; Train farmers and 2010 conduct awareness campaign Shifted to 2011 WP: Establishing of Nursery (Capacity building and reforestation - Kefraya West Bekaa in cooperation with UNV and Ministry of Environment 2. Conservation and 2.1. Establish and Increase the capacity of 2 Kfar Mishkeh: increase capacity of water management of water improved catchment ponds one in Rachaya (Kfar catchment from 15,000 m3 to 25,000m3, - collection of natural water for Mishkeh) and the other in WB (Ghaza) expanding the irrigated area and thus, irrigation Increased by 50,000 increasing by 60% the production of grasps m3 and vegetables, which benefit more than 300 local farmers. -

Batroun Koura Minié-Danniyé Zgharta Bcharré Tripoli SYRIA REFUGEE

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON North Governorate, Tripoli, Batroun, Bcharreh, El Koura, El Minieh-Dennieh, Zgharta Districts (T+5) Informal Settlements (IS) Locations and Number of Persons per IS As of 11 April 2014 Zouq Bhannine 006 Zouq Bhannine 007 Zouq Bhannine 003 (59) (198) Zouq Bhannine 005 N Zouq Bhannine 009 " (326) P P (185) 0 ' 0 (334) 3 Zouq Bhannine 008 ° P 4 1:10,000 P (128) 3 P P P Rihaniyet-Miniye P Zouq Bhannine 001 0 100 200 400 Meters ZPouq BhanniPneP Merkebta 040 P Merkebta 009 (207) (1P 02) Zouq Bhannine 010 PP (51) P P (152) P P P P PP Merkebta 026 P MinMieerkebta 014 PP P P (68) P PP PP PPP (110) PPP P P P Merkebta 002 PPPP P P P Minie 015 PP Raouda-Aadoua P PPP P (135) Minie 001 PP P (60) P P Minie 002 P Merkebta 005 Merkebta (386) P (57) P (400) Borj El-Yahoudiyé 001 P (116) Merkebta 007 Markabta 033 Deir Aammar Nabi Youcheaa Merkebta 004 P P (170) (85) (90) Borj El-Yahoudiye Nabi Youcheaa 001 Hraiqis P P Minie 016 P Minie 005 Mina N 3 (70) P Merkebta 001 Minie 022 P Mina N 1 Trablous jardins Beddaoui (143) (174) Mina N 2 (237) Mzraat Kefraya (113) Terbol-Miniye Raouda-Aadoua 003 P Raouda-Aadoua 001 Mina Jardin (105) Minie Boussit (47) Minie 004 P P Qarhaiya Aasaym out Minie 006 P Trablous Et-Tell Aalma 002 (464) Aazqai 001 Aazqai Mejdlaya 001 (105) Debaael PP P (70) Trablous Es-Souayqa P Hailan (100) Harf Es-Sayad (120) P Btermaz Minie 009 P Minie 017 P Aalma Qarne Kfar Chellane Beit Haouik (70) Miriata 003 P (158) Mejdlaiya Zgharta P (70P) P Harf Es-Sayad Tripoli Haouaret-Miniye Mrah Es-Srayj Trablous Ez-Zeitoun