Beyond Cement Competition 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Parliamentary Elections

issue number 121 |August 2012 CONTRACT WORKERS AND 3147 VACANT POSTS KOURA BY-ELECTION “THE MONTHLY” INTERVIEWS AMIN SALEH www.iimonthly.com # Published by Information International sal 2013 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS MARCH 8 FORCES WIN BY PROPORTIONALITY AND MARCH 14 BY PLURALITY Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros August INDEX 2012 4 2013 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 8 CONTRACT WORKERS AND 3147 VACANT POSTS AT ELÉCTRICITÉ DU LIBAN 11 KOURA BY-ELECTION 18 INCREASE IN INTERNAL SECURITY FORCES MEMBERS 21 SCHOOL-TO-WORK TRANSITION OF YOUNG WOMEN IN LEBANON P: 40 P: 24 24 MEDICAL SENSE & COMMON SENSE: DR. HANNA SAADAH 25 A HUMAN UPON REQUEST: ANTOINE BOUTROS 26 THE STATUS OF LEBANON’S RULE FROM 1861 UNTIL 2012 (1): SAID CHAAYA 27 INTERVIEW: AMIN SALEH 29 SEARCHING FOR HAPPINESS IN THE SPACE P: 8 30 TAMANNA 32 POPULAR CULTURE 40 GHASSAN TUEINI: STANCES AND 33 DEBUNKING MYTH #60: THE EIGHT-HOUR SLEEP STATEMENTS 34 MUST-READ BOOKS: THE REPUBLIC OF FOUAD 41 JUNE 2012 HIGHLIGHTS CHEHAB 45 ALGERIAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 35 MUST-READ CHILDREN’S BOOK: “THE CLOUD”, “FLYING” 47 REAL ESTATE PRICES IN LEBANON - JUNE 36 LEBANON FAMILIES: HOUBAISH FAMILIES 2012 37 DISCOVER LEBANON: KHAT EL-PETROL 48 FOOD PRICES - JUNE 2012 38 CIVIL STRIFE INTRO (6) 50 FACTS ON INJURIES AND VIOLENCE 50 BEIRUT RAFIC HARIRI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT - JUNE 2012 51 LEBANON STATS |EDITORIAL LONG LIVE THE TROIKA! The Hrawi prize bestowed upon Speaker Nabih Berri has awakened the memory of the Lebanese to the glories of the Hrawi era. -

The Haifa–Beirut–Tripoli Railway

APPENDIX 2 THE HAIFA–BEIRUT–TRIPOLI RAILWA Y By A. E. FIEL D Syria does not lend itself easily to railway construction . Very little such work was undertaken between the two world wars. In 1940, however, the possibility of Allied occupation of the Lebanon, and the hope that Turke y would join the Allies, made it very desirable that there should be a direct link between the standard gauge line from the British bases i n Egypt and Palestine then terminating at Haifa, and the northern Syrian system ending at Tripoli . Earlier the French administration had considered the linking of Haifa and Tripoli by a route along the coast, but the project had been shelved for fear that the port of Haifa would benefit at the expense of Beirut. In 1940 and 1941 Middle East Command had surveys made of various routes as far as the Lebanon border . From a map study the first route favoured was from Haifa round the north o f the Sea of Galilee to Rayak where the proposed railway would join th e Homs-Aleppo-Turkey standard gauge line . This was ruled out because it involved very heavy cutting in basalt . The next possibility considered was an extension of the line northwards from Haifa along the coast to th e Litani River and thence inland to Metulla-Rayak, but the route could not be explored before the conquest of Syria in July 1941 . It then became evident that much heavy bridge work would be necessary in the Litani gorges which would not be economically justifiable as a wartime project . -

MOST VULNERABLE LOCALITIES in LEBANON Coordination March 2015 Lebanon

Inter-Agency MOST VULNERABLE LOCALITIES IN LEBANON Coordination March 2015 Lebanon Calculation of the Most Vulnerable Localities is based on 251 Most Vulnerable Cadastres the following datasets: 87% Refugees 67% Deprived Lebanese 1 - Multi-Deprivation Index (MDI) The MDI is a composite index, based on deprivation level scoring of households in five critical dimensions: i - Access to Health services; Qleiaat Aakkar Kouachra ii - Income levels; Tall Meaayan Tall Kiri Khirbet Daoud Aakkar iii - Access to Education services; Tall Aabbas El-Gharbi Biret Aakkar Minyara Aakkar El-Aatiqa Halba iv - Access to Water and Sanitation services; Dayret Nahr El-Kabir Chir Hmairine ! v - Housing conditions; Cheikh Taba Machta Hammoud Deir Dalloum Khreibet Ej-Jindi ! Aamayer Qoubber Chamra ! ! MDI is from CAS, UNDP and MoSA Living Conditions and House- ! Mazraat En-Nahriyé Ouadi El-Jamous ! ! ! ! ! hold Budget Survey conducted in 2004. Bebnine ! Akkar Mhammaret ! ! ! ! Zouq Bhannine ! Aandqet ! ! ! Machha 2 - Lebanese population dataset Deir Aammar Minie ! ! Mazareaa Jabal Akroum ! Beddaoui ! ! Tikrit Qbaiyat Aakkar ! Rahbé Mejdlaiya Zgharta ! Lebanese population data is based on CDR 2002 Trablous Ez-Zeitoun berqayel ! Fnaydeq ! Jdeidet El-Qaitaa Hrar ! Michmich Aakkar ! ! Miriata Hermel Mina Jardin ! Qaa Baalbek Trablous jardins Kfar Habou Bakhaaoun ! Zgharta Aassoun ! Ras Masqa ! Izal Sir Ed-Danniyé The refugee population includes all registered Syrian refugees, PRL Qalamoun Deddé Enfé ! and PRS. Syrian refugee data is based on UNHCR registration Miziara -

Inter-Agency Q&A on Humanitarian Assistance and Services in Lebanon (Inqal)

INQAL- INTER AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON INTER-AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON (INQAL) Disclaimers: The INQAL is to be utilized mainly as a mass information guide to address questions from persons of concern to humanitarian agencies in Lebanon The INQAL is to be used by all humanitarian workers in Lebanon The INQAL is also to be used for all available humanitarian hotlines in Lebanon The INQAL is a public document currently available in the Inter-Agency Information Sharing web portal page for Lebanon: http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/documents.php?page=1&view=grid&Country%5B%5D=122&Searc h=%23INQAL%23 The INQAL should not be handed out to refugees If you and your organisation wish to publish the INQAL on any website, please notify the UNHCR Information Management and Mass Communication Units in Lebanon: [email protected] and [email protected] Updated in April 2015 INQAL- INTER AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON INTER-AGENCY Q&A ON HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE AND SERVICES IN LEBANON (INQAL) EDUCATION ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 FOOD ........................................................................................................................................................................ 35 FOOD AND ELIGIBILITY ............................................................................................................................................ -

Carriage of Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Among

International Journal of Infectious Diseases 45 (2016) 24–31 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Infectious Diseases jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijid Carriage of beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among nursing home residents in north Lebanon Iman Dandachi, Elie Salem Sokhn, Elie Najem, Eid Azar, Ziad Daoud * Faculty of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, University of Balamand, PO Box 33, Amioun, Beirut, Lebanon A R T I C L E I N F O S U M M A R Y Article history: Background: Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Enterobacteriaceae can cause severe infections with high Received 15 December 2015 morbidity, mortality, and health care costs. Individuals can be fecal carriers of these resistant organisms. Received in revised form 18 January 2016 Data on the extent of MDR Enterobacteriaceae fecal carriage in the community setting in Lebanon are very Accepted 10 February 2016 scarce. The aim of this study was to investigate the fecal carriage of MDR Enterobacteriaceae among the Corresponding Editor: Eskild Petersen, elderly residents of two nursing homes located in north Lebanon. Aarhus, Denmark. Methods: Over a period of 4 months, five fecal swab samples were collected from each of 68 elderly persons at regular intervals of 3–4 weeks. Fecal swabs were subcultured on selective media for the Keywords: screening of resistant organisms. The phenotypic detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Carriage (ESBL), AmpC, metallo-beta-lactamase (MBL), and Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) Nursing homes production was performed using the beta-lactamase inhibitors ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, Resistance phenylboronic acid, and cloxacillin. A temocillin disk was used for OXA-48. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Baalbek Hermel Zahleh Jbayl Aakar Koura Metn Batroun West Bekaa Zgharta Kesrouane Rachaiya Miniyeh-Danniyeh Bcharreh Baabda Aale

305 307308 Borhaniya - Rehwaniyeh Borj el Aarab HakourMazraatKarm el Aasfourel Ghatas Sbagha Shaqdouf Aakkar 309 El Aayoun Fadeliyeh Hamediyeh Zouq el Hosniye Jebrayel old Tekrit New Tekrit 332ZouqDeir El DalloumMqachrine Ilat Ain Yaaqoub Aakkar El Aatqa Er Rouaime Moh El Aabdé Dahr Aayas El Qantara Tikrit Beit Daoud El Aabde 326 Zouq el Hbalsa Ein Elsafa - Akum Mseitbeh 302 306310 Zouk Haddara Bezbina Wadi Hanna Saqraja - Ein Eltannur 303 Mar Touma Bqerzla Boustane Aartoussi 317 347 Western Zeita Al-Qusayr Nahr El Bared El318 Mahammara Rahbe Sawadiya Kalidiyeh Bhannine 316 El Khirbe El Houaich Memnaa 336 Bebnine Ouadi Ej jamous Majdala Tashea Qloud ElEl Baqie Mbar kiye Mrah Ech Chaab A a k a r Hmaire Haouchariye 34°30'0"N 338 Qanafez 337 Hariqa Abu Juri BEKKA INFORMALEr Rihaniye TENTEDBaddouaa El Hmaira SETTLEMENTS Bajaa Saissouq Jouar El Hachich En Nabi Kzaiber Mrah esh Shmis Mazraat Et Talle Qarqaf Berkayel Masriyeh Hamam El Minié Er Raouda Chane Mrah El Dalil Qasr El Minie El Kroum El Qraiyat Beit es Semmaqa Mrah Ez Zakbe Diyabiyeh Dinbou El Qorne Fnaydek Mrah el Arab Al Quasir 341 Beit el Haouch Berqayel Khraibe Fnaideq Fissane 339 Beit Ayoub El Minieh - Plot 256 Bzal Mishmish Hosh Morshed Samaan 340 Aayoun El Ghezlane Mrah El Ain Salhat El Ma 343 Beit Younes En Nabi Khaled Shayahat Ech Cheikh Maarouf Habchit Kouakh El Minieh - Plots: 1797 1796 1798 1799 Jdeidet El Qaitaa Khirbit Ej Jord En Nabi Youchaa Souaisse 342 Sfainet el Qaitaa Jawz Karm El Akhras Haouch Es Saiyad AaliHosh Elsayed Ali Deir Aamar Hrar Aalaiqa Mrah Qamar ed Dine -

Copyright© 2017 Mediterranean Marine Science

Mediterranean Marine Science Vol. 18, 2017 Introduced marine macroflora of Lebanon and its distribution on the Levantine coast BITAR G. Lebanese University, Faculty of Sciences, Hadaeth, Beirut, Lebanon RAMOS-ESPLÁ A. Centro de Investigación Marina de Santa Pola (CIMAR), Universidad de Alicante, 03080 Alicante OCAÑA O. Departamento de Oceanografía Biológica y Biodiversidad, Fundación Museo del Mar, Muelle Cañonero Dato s.n, 51001 Ceuta SGHAIER Y. Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas (RAC/SPA) FORCADA A. Departamento de Ciencias del Mar y Biología Aplicada, Universidad de Alicante, Po Box 99, Edificio Ciencias V, Campus de San Vicente del Raspeig, E-03080, Alicante VALLE C. Departamento de Ciencias del Mar y Biología Aplicada, Universidad de Alicante, Po Box 99, Edificio Ciencias V, Campus de San Vicente del Raspeig, E-03080, Alicante EL SHAER H. IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), Regional Office for West Asia Sweifiyeh, Hasan Baker Al Azazi St. no 20 - Amman VERLAQUE M. Aix Marseille University, CNRS/INSU, Université de Toulon, IRD, Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography (MIO), UM 110, GIS Posidonie, 13288 Marseille http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.1993 Copyright © 2017 Mediterranean Marine Science http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 04/08/2019 04:30:09 | To cite this article: BITAR, G., RAMOS-ESPLÁ, A., OCAÑA, O., SGHAIER, Y., FORCADA, A., VALLE, C., EL SHAER, H., & VERLAQUE, M. (2017). Introduced marine macroflora of Lebanon and its distribution on the Levantine coast. Mediterranean Marine Science, 18(1), 138-155. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.1993 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 04/08/2019 04:30:09 | Review Article Mediterranean Marine Science Indexed in WoS (Web of Science, ISI Thomson) and SCOPUS The journal is available on line at http://www.medit-mar-sc.net DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/mms.1993 The introduced marine macroflora of Lebanon and its distribution on the Levantine coast G. -

5 Million M2: When Will the State Recover Them?

issue number 158 |September 2015 SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT IN LEBANON HEFTY COST AND UNSOLVED CRISIS POSTPONING THE RELEASE OF LEBANON’S ARMY COMMANDER THE MONTHLY INTERVIEWS NABIL ZANTOUT www.monthlymagazine.com Published by Information International sal GENERAL MANAGER AT IBC USURPATION OF COASTAL PUBLIC PROPERTY 5 MILLION M2: WHEN WILL THE STATE RECOVER THEM? Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros September INDEX 2015 4 USURPATION OF COASTAL PUBLIC PROPERTY 5 MILLION M2: WHEN WILL THE STATE RECOVER THEM? 16 2013 CENTRAL INSPECTION REPORT 19 SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT IN LEBANON HEFTY COST AND UNSOLVED CRISIS 22 POSTPONING THE RELEASE OF LEBANON’S ARMY COMMANDER 24 JAL EL-DIB: BETWEEN THE TUNNEL AND THE BRIDGE 25 PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN: QONUNCHILIK PALATASI P: 28 P: 16 26 RASHID BAYDOUN (1889-1971) 28 INTERVIEW: NABIL ZANTOUT GENERAL MANAGER AT IBC 31 INJAZ LEBANON 33 POPULAR CULTURE 34 DEBUNKING MYTH#97: SHOULD WE BRUSH OUR TEETH IMMEDIATELY AFTER EATING? 35 MUST-READ BOOKS: DAR SADER- IN BEIRUT... A THOUGHT SPARKED UP 36 MUST-READ CHILDREN’S BOOK: THE BANANA P: 19 37 LEBANON FAMILIES: QARQOUTI FAMILIES 38 DISCOVER LEBANON: SMAR JBEIL 39 DISCOVER THE WORLD: NAURU 40 JULY 2015 HIGHLIGHTS 49 REAL ESTATE PRICES - JULY 2015 44 THIS MONTH IN HISTORY- LEBANON 50 DID YOU KNOW THAT?: 2014 FIFA WORLD CIVIL WAR DIARIES CUP THE ZGHARTA-TRIPOLI FRONT 40 YEARS AGO 50 RAFIC HARIRI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT 47 THIS MONTH IN HISTORY- ARAB WORLD - JORDAN TRAFFIC - JULY 2015 BLACK SEPTEMBER EVENTS 51 LEBANON’S STATS 48 TERRORIST GROUPS PRETENDING TO STAND FOR ISLAM (8) ANSAR AL-SHARIA’A: ORIGINATING FROM LIBYA AND ESPOUSING ISLAMIC SHARIA’A |EDITORIAL Iskandar Riachi Below are excerpts from chapter 40 of Iskandar Riachi’s book Before and After, which was published in Lebanon in the 1950s. -

Banks in Lebanon

932-933.qxd 14/01/2011 09:13 Õ Page 2 AL BAYAN BUSINESS GUIDE USEFUL NUMBERS Airport International Calls (100) Ports - Information (1) 628000-629065/6 Beirut (1) 580211/2/3/4/5/6 - 581400 - ADMINISTRATION (1) 629125/130 Internal Security Forces (112) Byblos (9) 540054 - Customs (1) 629160 Chika (6) 820101 National Defense (1701) (1702) Jounieh (9) 640038 Civil Defence (125) Saida (7) 752221 Tripoli (6) 600789 Complaints & Review (119) Ogero (1515) Tyr (7) 741596 Consumer Services Protection (1739) Police (160) Water Beirut (1) 386761/2 Red Cross (140) Dbaye (4) 542988- 543471 Electricity (145) (1707) Barouk (5) 554283 Telephone Repairs (113) Jounieh (9) 915055/6 Fire Department (175) Metn (1) 899416 Saida (7) 721271 General Security (1717) VAT (1710) Tripoli (6) 601276 Tyr (7) 740194 Information (120) Weather (1718) Zahle (8) 800235/722 ASSOCIATIONS, SYNDICATES & OTHER ORGANIZATIONS - MARBLE AND CEMENT (1)331220 KESRWAN (9)926135 BEIRUT - PAPER & PACKAGING (1)443106 NORTH METN (4)926072-920414 - PHARMACIES (1)425651-426041 - ACCOUNTANTS (1)616013/131- (3)366161 SOUTH METN (5)436766 - PLASTIC PRODUCERS (1)434126 - ACTORS (1)383407 - LAWYERS - PORT EMPLOYEES (1) 581284 - ADVERTISING (1)894545 - PRESS (1)865519-800351 ALEY (5)554278 - AUDITOR (1)322075 BAABDA (5)920616-924183 - ARTIST (1)383401 - R.D.C.L. (BUSINESSMEN) (1)320450 DAIR AL KAMAR (5)510244 - BANKS (1)970500 - READY WEAR (3)879707-(3)236999 - CARS DRIVERS (1)300448 - RESTAURANTS & CAFE (1)363040 JBEIL (9)541640 - CHEMICAL (1)499851/46 - TELEVISIONS (5)429740 JDEIDET EL METN (1)892548 - CONTRACTORS (5)454769 - TEXTILLES (5)450077-456151 JOUNIEH (9)915051-930750 - TOURISM JOURNALISTS (1)349251 - DENTISTS (1)611222/555 - SOCKS (9)906135 - TRADERS (1)347997-345735 - DOCTORS (1)610710 - TANNERS (9)911600 - ENGINEERS (1)850111 - TRADERS & IND. -

Layout CAZA AAKAR.Indd

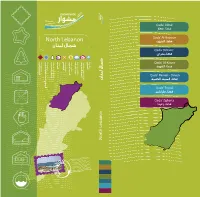

Qada’ Akkar North Lebanon Qada’ Al-Batroun Qada’ Bcharre Monuments Recreation Hotels Restaurants Handicrafts Bed & Breakfast Furnished Apartments Natural Attractions Beaches Qada’ Al-Koura Qada’ Minieh - Dinieh Qada’ Tripoli Qada’ Zgharta North Lebanon Table of Contents äÉjƒàëªdG Qada’ Akkar 1 QɵY AÉ°†b Map 2 á£jôîdG A’aidamoun 4-27 ¿ƒeó«Y Al-Bireh 5-27 √ô«ÑdG Al-Sahleh 6-27 á∏¡°ùdG A’andaqet 7-28 â≤æY A’arqa 8-28 ÉbôY Danbo 9-29 ƒÑfO Deir Jenine 10-29 ø«æL ôjO Fnaideq 11-29 ¥ó«æa Haizouq 12-30 ¥hõ«M Kfarnoun 13-30 ¿ƒfôØc Mounjez 14-31 õéæe Qounia 15-31 É«æb Akroum 15-32 ΩhôcCG Al-Daghli 16-32 »∏ZódG Sheikh Znad 17-33 OÉfR ï«°T Al-Qoubayat 18-33 äÉ«Ñ≤dG Qlaya’at 19-34 äÉ©«∏b Berqayel 20-34 πjÉbôH Halba 21-35 ÉÑ∏M Rahbeh 22-35 ¬ÑMQ Zouk Hadara 23-36 √QGóM ¥hR Sheikh Taba 24-36 ÉHÉW ï«°T Akkar Al-A’atiqa 25-37 á≤«à©dG QɵY Minyara 26-37 √QÉ«æe Qada’ Al-Batroun 69 ¿hôàÑdG AÉ°†b Map 40 á£jôîdG Kouba 42-66 ÉHƒc Bajdarfel 43-66 πaQóéH Wajh Al-Hajar 44-67 ôéëdG ¬Lh Hamat 45-67 äÉeÉM Bcha’aleh 56-68 ¬∏©°ûH Kour (or Kour Al-Jundi) 47-69 (…óæédG Qƒc hCG) Qƒc Sghar 48-69 Qɨ°U Mar Mama 49-70 ÉeÉe QÉe Racha 50-70 É°TGQ Kfifan 51-70 ¿ÉØ«Øc Jran 52-71 ¿GôL Ram 53-72 ΩGQ Smar Jbeil 54-72 π«ÑL Qɪ°S Rachana 55-73 ÉfÉ°TGQ Kfar Helda 56-74 Gó∏MôØc Kfour Al-Arabi 57-74 »Hô©dG QƒØc Hardine 58-75 øjOôM Ras Nhash 59-75 ¢TÉëf ¢SGQ Al-Batroun 60-76 ¿hôàÑdG Tannourine 62-78 øjQƒæJ Douma 64-77 ÉehO Assia 65-79 É«°UCG Qada’ Bcharre 81 …ô°ûH AÉ°†b Map 82 á£jôîdG Beqa’a Kafra 84-97 GôØc ´É≤H Hasroun 85-98 ¿hô°üM Bcharre 86-97 …ô°ûH Al-Diman 88-99 ¿ÉªjódG Hadath -

LEBANONLEBANON Outline

Edwina TANIOS ‐‐ LEBANONLEBANON Outline: • The country of Lebanon • American University of Beirut • My Major • Origin: “Lebanon” is derived from “lbn”= “ white” referring to the snow that covers Mount Lebanon which extends across the country . • Location: in the Middle East bordering the Mediterranean Sea, between Syria and IlIsrael. • Area: 10 452 square kilometers . • Population: 4 140 289 . (Christian and Islamic) About 10 million Lebanese people live outside Lebanon. • Geographic features: Many popular rivers and streams Alternation of low lands and high lands that run parallel with a North to South direction One of main symbols of the country is the Lebanon Cedar (Cedrus libani). It grows in Western Asia (Lebanon, Syria, parts of Turkey). Lebanon is a country where the oldest, continuously populated city in the world is located. Byblos or Jbeil, as it is known today, is at least 7000 years old. Phoenicians used to believe that the city was founded by the god El. The Lebanon Cedar can be seen on the Lebanese flag. Official language: Arabic . French, Armenian, Greek and English are spoken too. In everyday life many people actually speak some combination of these languages. The most common combination is the Arabic‐French one. The Arabic alphabet: Climate Mediterranean climate 1. Summer is long, hot and dry (June‐September) 20 to 32 °C. 2. Fall is a transitional season with a lowering of tttemperature and a little rain (Oct ob er‐NNb)ovember) 5 to 20 °C. 3. winter is cool and rainy : major rain after December, the amount of rainfall varies greatly from one year to another, frosts during winter and snow on high mountains (December‐March) 10 to 20 °C.