Consolidating Mali's Decentralized Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gold from Children's Hands

SO M O Gold from children’s hands Use of child-mined gold by the electronics sector Irene Schipper & Esther de Haan & Mark van Dorp November 2015 Colophon Gold from children’s hands Use of child-mined gold by the electronics sector November 2015 Authors: Irene Schipper and Esther de Haan With contributions of: Meike Remmers and Vincent Kiezebrink Mali field research: Mark van Dorp Layout: Frans Schupp Photos: Mark van Dorp / SOMO en ELEFAN-SARL ISBN: 978-94-6207-075-2 Published by: Commisioned by: Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale Stop Child Labour Ondernemingen (SOMO) ‘Stop Child Labour – School is the best Centre for Research on Multinational place to work’ (SCL) is a coalition Corporations coordinated by Hivos. The coalition The Centre for Research on Multina- consists of the Algemene Onderwijs- tional Corporations (SOMO) is an bond (AOb), FNV Mondiaal, Hivos, the independent, not-for-profit research and India Committee of the Netherlands network organisation working on social, (ICN), Kerk in Actie & ICCO ecological and economic issues related Cooperation, Stichting Kinderpostzegels to sustainable development. Since 1973, Nederland and local organisations in the organisation investigates multina- Asia, Africa and Latin America. tional corporations and the conse- www.stopchildlabour.org quences of their activities for people and the environment around the world. Sarphatistraat 30 1018 GL Amsterdam The Netherlands T + 31 (20) 6391291 F + 31 (20) 6391321 [email protected] www.somo.nl Gold from children’s hands Use of child-mined gold by the electronics sector SOMO Irene Schipper, Esther de Haan and Mark van Dorp Amsterdam, November 2015 Contents Glossary ................................................................................................................ 4 Acronyms .............................................................................................................. -

Agricultural Diversification in Mali: the Case of the Cotton Zone of Koutiala

AGRICULTURAL DIVERSIFICATION IN MALI: THE CASE OF THE COTTON ZONE OF KOUTIALA By Mariam Sako Thiam A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics – Master of Science 2014 ABSTRACT AGRICULTURAL DIVERSIFICATION IN MALI: THE CASE OF THE COTTON ZONE OF KOUTIALA By Mariam Sako Thiam Cotton production plays a central role in the economy and the livelihood of cotton growers in the Koutiala area of Mali. Despite all the investment made in the cotton zones, the cotton farmers in Koutiala suffer substantially from uncertainties in the cotton subsector linked to prices, timely payment, and to the future structure of the industry. This study analyzes empirically how cotton growers with different agricultural characteristics coped with these uncertainties over the period 2006-2010. The data used in this study were collected during the survey that covered 150 households in the Koutiala area during three cropping seasons: 2006-07, 2008-09 and 2009- 10.The results show that despite income diversification among the households surveyed in Koutiala, agricultural production remains the main source of income. The findings also show that the farmers who continued to grow cotton during the three years of the survey and those who started producing cotton after year one diversified within the agricultural sector by producing more peanuts and cowpeas while the farmers who dropped out of cotton production after year one of the survey diversified toward non-farm activities such as commerce and self. We also found that the non-cotton growers are the poorest group of farmers, with less agricultural equipment and labor as well as less overall wealth, limiting their potential to invest in farm activities and start an off-farm business. -

Apiculture Au Sud Mali

TG01 / 2008 Transfert et de la gestion décentralisée Rapport d’étude : Problématique de l’immatriculation, du trans- fert et de la gestion dé- centralisée des équipe- ments et infrastructures productives Intercooperation Jèkasy –www.dicsahel.org Maître Oumar Cissé Maître Tignougou Sanogo Jèkasy Sikasso J Problématique de l’immatriculation, du transfert et de la gestion décentralisée des équipements et infrastructures productives Rapport d’étude Maître Oumar Cissé Maître Tignougou Sanogo Avril 2008 2 TABLE DES MATIERES I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 6 II. ANALYSE CRITIQUE DU CADRE SOCIO-JURIDIQUE .......................................................................7 2.1 CONTEXTE................................................................................................................................................ 7 2.2 POUVOIRS DE L’ETAT SUR LES INFRASTRUCTURES .................................................................................. 7 2.3 PREROGATIVES DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES SUR LES INFRASTRUCTURES....................................8 2.3.1 Appropriation communale des équipements ....................................................................................... 9 2.3.2 Gestion communale des équipements................................................................................................ 10 2.3 LES PRETENTIONS DES POPULATIONS SUR LES INFRASTRUCTURES.........................................................10 -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

Evaluation De L'état Nutritionnel Des Enfants De 6 À 59 Mois Dans Le Cercle De Koutiala

REPUBLIQUE DU MALI Ministère de l’Enseignement Un Peuple-Un But-Une Foi Supérieur et de La Recherche Scientifique FACULTE DE MEDECINE ET D’ODONTO STOMATOLOGIE ANNEE UNIVERSITAIRE: 2012-2013 N°………/ Evaluation de l’état nutritionnel des enfants de 6 à 59 mois dans le cercle de Koutiala (Région de Sikasso) en 2012 THÈSE Présentée et soutenue publiquement le 28 Mai 2013 Devant la Faculté de Médecine et d’Odontostomatologie PAR Mr : Bakary Moulaye KONE Pour obtenir le Grade de Docteur en Médecine (DIPLOME D’ETAT) Jury Président : Pr Samba DIOP Membre : Dr Fatou DIAWARA Co-directeur : Dr Kadiatou KAMIAN Directeur : Pr Akory AG IKNANE Cette Etude a été financée et commanditée par MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières France) FACULTE DE MEDECINE ET D’ODONTO-STOMATOLOGIE ANNEE UNIVERSITAIRE 2012-2013 ADMINISTRATION DOYEN : FEU ANATOLE TOUNKARA - PROFESSEUR 1er ASSESSEUR : BOUBACAR TRAORE - MAITRE DE CONFERENCES 2ème ASSESSEUR : IBRAHIM I. MAIGA - PROFESSEUR SECRETAIRE PRINCIPAL : IDRISSA AHMADOU CISSE - MAITRE DE CONFERENCES AGENT COMPTABLE : MADAME COULIBALY FATOUMATA TALL - CONTROLEUR DES FINANCES LES PROFESSEURS HONORAIRES Mr Alou BA Ophtalmologie † Mr Bocar SALL Orthopédie Traumatologie - Secourisme Mr Yaya FOFANA Hématologie Mr Mamadou L. TRAORE Chirurgie Générale Mr Balla COULIBALY Pédiatrie Mr Mamadou DEMBELE Chirurgie Générale Mr Mamadou KOUMARE Pharmacognosie Mr Ali Nouhoum DIALLO Médecine interne Mr Aly GUINDO Gastro-Entérologie Mr Mamadou M. KEITA Pédiatrie Mr Siné BAYO Anatomie-Pathologie-Histoembryologie Mr Sidi Yaya SIMAGA Santé Publique Mr Abdoulaye Ag RHALY Médecine Interne Mr Boulkassoum HAIDARA Législation Mr Boubacar Sidiki CISSE Toxicologie Mr Massa SANOGO Chimie Analytique Mr Sambou SOUMARE Chirurgie Générale Mr Sanoussi KONATE Santé Publique Mr Abdou Alassane TOURE Orthopédie - Traumatologie Mr Daouda DIALLO Chimie Générale & Minérale Mr Issa TRAORE Radiologie Mr Mamadou K. -

R E GION S C E R C L E COMMUNES No. Total De La Population En 2015

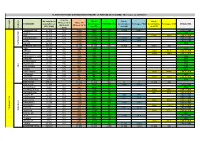

PLANIFICATION DES DISTRIBUTIONS PENDANT LA PERIODE DE SOUDURE - Mise à jour au 26/05/2015 - % du CH No. total de la Nb de Nb de Nb de Phases 3 à 5 Cibles CH COMMUNES population en bénéficiaires TONNAGE CSA bénéficiaires Tonnages PAM bénéficiaires Tonnages CICR MODALITES (Avril-Aout (Phases 3 à 5) 2015 (SAP) du CSA du PAM du CICR CERCLE REGIONS 2015) TOMBOUCTOU 67 032 12% 8 044 8 044 217 10 055 699,8 CSA + PAM ALAFIA 15 844 12% 1 901 1 901 51 CSA BER 23 273 12% 2 793 2 793 76 6 982 387,5 CSA + CICR BOUREM-INALY 14 239 12% 1 709 1 709 46 2 438 169,7 CSA + PAM LAFIA 9 514 12% 1 142 1 142 31 1 427 99,3 CSA + PAM SALAM 26 335 12% 3 160 3 160 85 CSA TOMBOUCTOU TOMBOUCTOU TOTAL 156 237 18 748 18 749 506 13 920 969 6 982 388 DIRE 24 954 10% 2 495 2 495 67 CSA ARHAM 3 459 10% 346 346 9 1 660 92,1 CSA + CICR BINGA 6 276 10% 628 628 17 2 699 149,8 CSA + CICR BOUREM SIDI AMAR 10 497 10% 1 050 1 050 28 CSA DANGHA 15 835 10% 1 584 1 584 43 CSA GARBAKOIRA 6 934 10% 693 693 19 CSA HAIBONGO 17 494 10% 1 749 1 749 47 CSA DIRE KIRCHAMBA 5 055 10% 506 506 14 CSA KONDI 3 744 10% 374 374 10 CSA SAREYAMOU 20 794 10% 2 079 2 079 56 9 149 507,8 CSA + CICR TIENKOUR 8 009 10% 801 801 22 CSA TINDIRMA 7 948 10% 795 795 21 2 782 154,4 CSA + CICR TINGUEREGUIF 3 560 10% 356 356 10 CSA DIRE TOTAL 134 559 13 456 13 456 363 0 0 16 290 904 GOUNDAM 15 444 15% 2 317 9 002 243 3 907 271,9 CSA + PAM ALZOUNOUB 5 493 15% 824 3 202 87 CSA BINTAGOUNGOU 10 200 15% 1 530 5 946 161 4 080 226,4 CSA + CICR ADARMALANE 1 172 15% 176 683 18 469 26,0 CSA + CICR DOUEKIRE 22 203 15% 3 330 -

Analyse the Perception Level and the Causes of Migration in Mali

1 Analyse the perception level and the causes of 2 migration in Mali. 3 4 Abstract: 5 Subsistence farmers in Sahelian Africa are highly exposed to the environmental challenges 6 associated with climate change. Temporary or Permanent emigration can offer to an 7 individual or household the opportunity to cop against these special effects. One of the 8 most important challenge to quantifying the impact of climate change on emigration in 9 Mali is lack of accurate temporal and spatial data. Emigration data must be adequately 10 detailed to take in both long distances and short distances. The objective of this research 11 was to identify the socioeconomic characteristics of migrants based on the push factors. 12 For instance, to identify the characteristics of people who migrant due to bad weather or 13 environmental challenges. From the result, the factors that significantly influenced 14 migration were sex, age and age squared, household size, labour constraint, and location. 15 Multinomial logistic regression was used to analyse the subject. 16 Key words: migration drivers, multinomial logit, rural Mali, environmental challenges. 17 INTRODUCTION 18 Even if movement is a fundamental part of human being, in fact Mali has a long history of 19 migration particularly emigration. Recently it has become an important transit place for 20 migratory flows within the Sahelian region and beyond. The country is specific by its 21 population involved in migration issue that linked to cultural practices in using migration 22 as rite of road for young men. Mali has been experiencing seasonal and circular migration 23 as well as nomadic and pastoral movements. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Perceptions and Adaptations to Climate Change in Southern Mali

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 12 March 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202103.0353.v1 Perceptions and adaptations to climate change in Southern Mali Tiémoko SOUMAORO PhD student at the UFR of Economics and Management, Gaston Berger University (UGB) of Saint-Louis, Senegal. [email protected] ABSTRACT This study aims to determine the impact of climate change on market garden production in the extreme south of Mali through the perception and adaptation of market gardeners to climatic phenomena. The study used two models, namely the probit selection and Heckman results models and multinomial logistic regression, based on data collected from producers. A total of 194 producers were surveyed. The results of Heckman's probit model indicate that experience in agriculture and the educational level of the producers are the two main determinants of producers' perception and simultaneous adaptation to climate change. Among these variables agricultural experience is both positively and negatively correlated with perception. Keywords: Adaptation, climate change, southern Mali, Heckman probit, vegetable production 1. INTRODUCTION Climate change and its impacts have now become one of the greatest challenges for humanity, its environment and its economies (IPCC, 2013). At the global level, climate change is reflected in the rise in the average temperature of the planet, the melting of glaciers, the rise in sea level and the increase in the frequency of extreme events, the disappearance of species of animal origin, changes in rainfall patterns, etc. The average temperature in the world will increase by 1.8°C to 4°C, and in the worst case 6.4°C by the end of this century (IPCC, 2007). -

Peacebuilding Fund

Highlights #15 | April 2016 CRZPC: enlarged session with donors and Monthly Bulletin some iNGOs Trust Fund: new equipment for the MOC HQ in Gao Role of the S&R Section Peacebuilding Fund: UNDP & UNIDO support income generating activities In support to the Deputy Special Representative Through this monthly bulletin, we provide regular Timbuktu: support to the Préfecture and of the Secretary-General (DSRSG), Resident updates on stabilization & recovery developments women associations (QIPs) Coordinator (RC) and Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) and activities in the north of Mali. The intended Mopti: gardening in Sévaré prison (QIP video) in her responsibilities to lead the United Nations’ audience is the section’s main partners including Bamako: “MINUSMA in front of youths” contribution to Mali’s reconstruction efforts, the MINUSMA military and civilian components, UNCT awareness-raising day Stabilization & Recovery section (S&R) promotes and international partners. More QIPs launched in northern regions synergies between MINUSMA, the UN Country Team and other international partners. For more information: Gabriel Gelin, Information Specialist (S&R Main Figures section) - [email protected] QIPs 2015-2016: 58 projects with 15 completed and 43 under implementation over a total budget Donor Coordination and Partnerships of 4 million USD (167 projects since 2013) Peacebuilding Fund (PBF): 5 projects started On 8th of April, donors and some epidemics, (3) support to medicine provision in 2015 over 18 months for a total budget of 1. international NGOs met for the and (4) strengthening of the health information 10,932,168 USD monthly enlarged session of the Commission system. Partners in presence recommended that Trust Fund (TF): 13 projects completed/nearing Réhabilitation des Zones Post-Conflit (CRZPC). -

USAID/ Mali SIRA

USAID/ Mali SIRA Selective Integrated Reading Activity Quarterly Report April to June 2018 July 30, 2018 Submitted to USAID/Mali by Education Development Center, Inc. in accordance with Task Order No. AID-688-TO-16-00005 under IDIQC No. AID-OAA-I-14- 00053. This report is made possible by the support of the American People jointly through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Government of Mali. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Education Development Center, Inc. (EDC) and, its partners and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Table of Contents ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... 2 I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 3 II. Key Activities and Results ....................................................................................................... 5 II.A. – Intermediate Result 1: Classroom Early Grade Reading Instruction Improved ........................ 5 II.A.1. Sub-Result 1.1: Student’s access to evidence-based, conflict and gender sensitive, early Grade reading material increased .................................................................................................. 5 II.A.2. Sub IR1.2: Inservice teacher training in evidence-based early Grade reading improved ..... 6 II.A.3. Sub-Result 1.3: Teacher coaching and supervision -

Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019

FEWS NET Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019 MALI ENHANCED MARKET ANALYSIS JUNE 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’Famine views Early expressed Warning inSystem this publications Network do not necessarily reflect the views of the 1 United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgments FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Mali who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Mali Enhanced Market Analysis. Washington, DC: FEWS NET.