Lessons from San Francisco's Implementation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting Minutes

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEETING MINUTES Tuesday, August 25, 2020 - 2:00 PM Held via Videoconference (remote public access provided via teleconference) www.sfgovtv.org Regular Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman, Yee, Ronen 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Peskin, Haney 10:00 AM Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Haney, Fewer, Mar (Alt), Commissioners Moliga, Collins, Cook (Alt), 10:00 AM Trustees Randolph, Williams, Selby (Alt) Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Peskin, Safai, Preston 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Ronen, Stefani, Mar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Volume 115 Number 34 Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes 8/25/2020 Members Present: Sandra Lee Fewer, Matt Haney, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, Dean Preston, Hillary Ronen, Ahsha Safai, Catherine Stefani, Shamann Walton, and Norman Yee The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco met in regular session through videoconferencing, and provided public comment through teleconferencing, on Tuesday, August 25, 2020, with President Norman Yee presiding. -

Santa Comes to Cole Street on Sunday, December 1 San

COLE VALLEY IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION CVolume XXXIIIVIA SERVING COLE VALLEY AND NEWSTHE GREATER HAIGHT ASHBURY WINTER 2019 Santa Comes to Cole Street San Francisco Beautiful Hon- on Sunday, December 1 ors CVIA for “Clean Cole” Come and have your picture taken with Santa without At its annual awards the hassle of driving to a mall or waiting in long lines. The ceremony at Marines proceeds help fund the Clean Cole Street project. Memorial Club on Oc- tober 21, CVIA board Loic Nicolas, a popular photographer with consistent member Shannon Coo- 5-star reviews on Yelp (and a CVIA member), originated per Hock accepted an award on behalf of CVIA “for outstanding contribution to beautify- ing San Francisco,” for its Clean Cole project in which the commercial area of Cole Valley is swept every day (twice CVIA board member Shannon Cooper Hock a day on weekdays), by accepts commendation for CVIA. CleanScapes. Dean Preston Elected D5 Supe Photo: Loic Nicolas Loic Photo: With all eyes on the city’s only supervisorial race, it was a spirited match between two strong candidates that got down and dirty toward the end. This was Dean Preston’s second run for the District 5 seat Santa explains the fine points of the holiday season and the virtue of gen- and he was fighting for erosity to Jackson Arnold. (Just kidding.) his political life. When the results showed that this fundraising idea and annually donates a day of his time he had won, he knew it for the good of his neighborhood. was a short-term victo- As always, Chuck Canepa is our handsome Santa. -

December 7, 2020 by Email San Francisco Board of Supervisors Board of Supervisor, District 1, Sandra Lee Fewer Board of Supervis

& Karl Olson [email protected] December 7, 2020 By Email San Francisco Board of Supervisors [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 1, Sandra Lee Fewer [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 2, Catherine Stefani [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 3, Aaron Peskin [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 4, Gordon Mar [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 5, Dean Preston [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 6 Matt Haney [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 7, Norman Yee [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 8 Rafael Mandelman [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 9, Hillary Ronen [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 10, Shamann Walton [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 11, Ahsha Safaí [email protected] 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place City Hall, Room 244 San Francisco, Ca. 94102-4689 Re: Legal Notices to Marina Times (Scheduled for Hearing December 8, 2020) Dear Members of the Board of Supervisors: I am writing on behalf of my client the Marina Times (and its editor in chief Susan Dyer Reynolds), which has been singled out from other independent newspapers in the City qualified to receive legal notices under 1994’s Proposition J because it dared to exercise its First Amendment rights and criticize people in public office. It appears that peacefully exercising First Amendment rights, which can get you killed in some countries, may get you punished in San Francisco even by people who call themselves progressive. A little background is in order. -

Board of Supervisors City and County of San Francisco Agenda

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO AGENDA Watch SF Cable Channel 26, 78, or 99 (depending on your provider) Watch www.sfgovtv.org PUBLIC COMMENT CALL-IN 1 (415) 655-0001/ Meeting ID: 187 789 0947 # # Tuesday, May 18, 2021 - 2:00 PM Regular Meeting SHAMANN WALTON, PRESIDENT CONNIE CHAN, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, MYRNA MELGAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board Agendas of the Board of Supervisors are available on the internet at www.sfbos.org BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors Haney, Safai, Mar, Ronen, Walton 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Haney, Safai, Mar 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Preston, Chan, Mandelman 10:00 AM Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Melgar, Preston, Peskin 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mar, Stefani, Haney 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Peskin, Mandelman, Chan 10:00 AM Youth, Young Adult, and Families Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Ronen, Safai, Melgar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Agenda Item Information Each item on the Consent or Regular agenda may include the following documents: 1) Legislation 2) Budget and Legislative Analyst report 3) Department or Agency cover letter and/or report 4) Public correspondence These items will be available for review at City Hall, 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place, Room 244, Reception Desk. -

Meeting Minutes - Draft

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEETING MINUTES - DRAFT Tuesday, March 31, 2020 - 2:00 PM Held via Videoconference (remote public access provided) www.sfgovtv.org Special Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman, Yee, Ronen 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Walton, Mandelman 10:00 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Peskin, Haney 10:00 AM Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Haney, Fewer, Mar (Alt), Commissioners Moliga, Collins, Cook (Alt), 10:00 AM Trustees Randolph, Williams, Selby (Alt) Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Peskin, Safai, Preston 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Ronen, Stefani, Mar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes - Draft 3/31/2020 Members Present: Sandra Lee Fewer, Matt Haney, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, Dean Preston, Hillary Ronen, Ahsha Safai, Catherine Stefani, Shamann Walton, and Norman Yee The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco met in special session through videoconferencing on Tuesday, March 31, 2020, with President Norman Yee presiding. President Yee called the meeting to order at 2:03 p.m. -

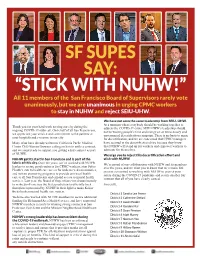

SF BOS Letter to CPMC Members

SF SUPES SAY: “STICK WITH NUHW!” All 11 members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors rarely vote unanimously, but we are unanimous in urging CPMC workers to stay in NUHW and reject SEIU-UHW. We have not seen the same leadership from SEIU–UHW. At a moment when everybody should be working together to Thank you for your hard work serving our city during the address the COVID-19 crisis, SEIU-UHW’s leadership should ongoing COVID-19 outbreak. On behalf of all San Franciscans, not be wasting people’s time and energy on an unnecessary and we appreciate your service and commitment to the patients at unwarranted decertification campaign. There is no basis to argue your hospitals and everyone in our city. for decertification, and we are concerned that CPMC managers Many of us have already written to California Pacfic Medical have assisted in the decertification drive because they know Center CEO Warren Browner calling on him to settle a contract, that NUHW will stand up for workers and empower workers to and we stand ready to support you getting a fair contract as part advocate for themselves. of NUHW. We urge you to reject this decertification effort and NUHW got its start in San Francisco and is part of the stick with NUHW. fabric of this city. Over the years, we’ve worked with NUHW We’re proud of our collaboration with NUHW and its members leaders to secure good contracts for CPMC workers, stop Sutter over the years, and we want you to know that we remain 100 Health’s cuts to health care access for underserved communities, percent committed to working with NUHW to protect your and initiate pioneering programs to provide universal health safety during the COVID-19 pandemic and secure another fair care to all San Franciscans and expand access to mental health contract that all of you have clearly earned. -

Board of Supervisors City and County of San Francisco Agenda

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO AGENDA Watch SF Cable Channel 26, 78, or 99 (depending on your provider) Watch www.sfgovtv.org PUBLIC COMMENT CALL-IN 1 (415) 655-0001/ Meeting ID: 187 347 6894 # # Tuesday, April 6, 2021 - 2:00 PM Regular Meeting SHAMANN WALTON, PRESIDENT CONNIE CHAN, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, MYRNA MELGAR, AARON PESKIN, DEAN PRESTON, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board Agendas of the Board of Supervisors are available on the internet at www.sfbos.org BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Appropriations Committee Wednesday Supervisors Haney, Safai, Mar, Ronen, Walton 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Haney, Safai, Mar 10:30 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Preston, Chan, Mandelman 10:00 AM Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Melgar, Preston, Peskin 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mar, Stefani, Haney 10:00 AM Youth, Young Adult, and Families Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Ronen, Safai, Melgar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Agenda Item Information Each item on the Consent or Regular agenda may include the following documents: 1) Legislation 2) Budget and Legislative Analyst report 3) Department or Agency cover letter and/or report 4) Public correspondence These items will be available for review at City Hall, 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place, Room 244, Reception Desk. Meeting Procedures The Board of Supervisors is the legislative body of the City and County of San Francisco. -

72 Hour Notice

San Francisco Democratic County Central Committee Special Meeting Wednesday, August 5, 2020 6:30pm Virtual Meeting via Zoom Video Call (More details to be provided) 72 Hour Meeting Agenda ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Call to Order and Roll Call Call to Order by Chair, David Campos. Roll Call of Members: John Avalos, Keith Baraka, Gloria Berry, David Campos, Queena Chen, Bevan Dufty, Peter Gallotta, Matt Haney, Anabel Ibáñez, Jane Kim, Leah LaCroix, Janice Li, Suzy Loftus, Li Miao Lovett, Honey Mahogany, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Faauuga Moliga, Carolina Morales, Mano Raju, Hillary Ronen, Amar Thomas, Nancy Tung, Shanell Williams. Ex-Officio Members: U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein; Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi; U.S. House Representative Jackie Speier; Lieutenant Governor Eleni Kounalakis, State Treasurer Fiona Ma; Board of Equalization Member Malia Cohen, State Senator Scott Wiener; Assemblymember Phil Ting and Assemblymember David Chiu. 2. Approval of Meeting Agenda (Discussion and possible action) Discussion and possible action regarding the approval of this agenda. 3. Approval of July Meeting Minutes (Discussion and possible action) Approval of the minutes of the DCCC’s meeting of July 22, 2020 (minutes attached). 4. Interviews of Qualified Local Measures (https://sfelections.sfgov.org/measures) - Affordable Housing Authorization (Ordinance) - Sheriff Oversight (Charter Amendment) - Police Staffing -

Page Street at Masonic Avenue

SFMTA - TASC SUMMARY SHEET PreStaff_Date: 11/3/2020 Public Hearing Consent No objections:____________ Requested_by: SFMTA X Public Hearing Regular Item Held:________________ Handled: Daniel Carr Informational / Other Other:__________________ Section Head : MS PH - Regular Location: Page Street at Masonic Street Subject: Bike Share Station PROPOSAL / REQUEST: ESTABLISH - NO STOPPING EXCEPT BICYCLES ESTABLISH - BIKE SHARE STATION Page Street, south side, from Masonic Avenue to 90 feet easterly (82-foot station with red zones either side) Supervisor District 5) Proposing a Bay Wheels bike share station in the parking lane on Page Street adjacent to 1100 Masonic Avenue, diagonally across the street from St. Agnes Church Daniel Carr, [email protected] BACKGROUND INFORMATION / COMMENTS Stations with bicycles are approximately 6 feet long and 4 feet tall with a kiosk approximately 7.8 feet tall at the eastern end of the station. Stations will be solar powered via a panel system that extends vertically from the kiosk No excavation is necessary. - This site is located on a street with Class III bike route. This street is also a Slow Street. - This site is located on a street with no MUNI lines. - Lyft conducted outreach to the adjacent multi-unit residential building and received one response in opposition. -This location was also shared with Parkwide bike rentals, and they were supportive of this location. - This station was also placed on an online neighborhood survey. - This station was shared with multiple neighborhood groups and the District -

Dean Preston for Supervisor 2019 Albany Aroyan MAILING ADDRESS

COVER PAGE Recipient Committee Date Stamp Campaign Statement CALIFORNIA 460 Cover Page FORM (Government Code Sections 84200-84216.5) E-Filed 01/31/2019 Statement covers period Date of election if applicable: 18:32:52 Page 1 of 75 (Month, Day, Year) 01/01/2018 from Filing ID: For Official Use Only 176222314 11/05/2019 SEE INSTRUCTIONS ON REVERSE through 12/31/2018 1. Type of Recipient Committee: All Committees – Complete Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4. 2. Type of Statement: X Officeholder, Candidate Controlled Committee Primarily Formed Ballot Measure Preelection Statement Quarterly Statement State Candidate Election Committee Committee X Semi-annual Statement Special Odd-Year Report Recall Controlled Termination Statement Supplemental Preelection (Also Complete Part 5) Sponsored (Also file a Form 410 Termination) Statement - Attach Form 495 (Also Complete Part 6) General Purpose Committee Amendment (Explain below) Sponsored Primarily Formed Candidate/ Small Contributor Committee Officeholder Committee Political Party/Central Committee (Also Complete Part 7) 3. Committee Information I.D. NUMBER Treasurer(s) 1408942 COMMITTEE NAME (OR CANDIDATE’S NAME IF NO COMMITTEE) NAME OF TREASURER Dean Preston for Supervisor 2019 Albany Aroyan MAILING ADDRESS STREET ADDRESS (NO P.O. BOX) CITY STATE ZIP CODE AREA CODE/PHONE San Francisco CA 94114 (415)678-7089 CITY STATE ZIP CODE AREA CODE/PHONE NAME OF ASSISTANT TREASURER, IF ANY San Francisco CA 94114 (510)367-1984 MAILING ADDRESS (IF DIFFERENT) NO. AND STREET OR P.O. BOX MAILING ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE AREA CODE/PHONE CITY STATE ZIP CODE AREA CODE/PHONE San Francisco CA 94117 OPTIONAL: FAX / E-MAIL ADDRESS OPTIONAL: FAX / E-MAIL ADDRESS [email protected] [email protected] 4. -

This Version of the Voter Information Pamphlet Does Not Include Your Sample Ballot, Because Different Versions of the Sample Ballot Apply Throughout San Francisco

John Arntz, Director NOTE: This version of the Voter Information Pamphlet does not include your sample ballot, because different versions of the sample ballot apply throughout San Francisco. Your sample ballot can be accessed, along with the location of your polling place, at sfelections.org/voterportal. Also, the pages in this online version of the pamphlet are arranged in a different order from the printed version. For this reason, we are unable to provide a Table of Contents. To find specific information, please refer to the bookmarks on the left side of this file. English (415) 554-4375 sfelections.org 中文 (415) 554-4367 Fax (415) 554-7344 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place Español (415) 554-4366 TTY (415) 554-4386 City Hall, Room 48, San Francisco, CA 94102 Filipino (415) 554-4310 City and County of San Francisco Department of Elections Voter Information Pamphlet & Sample Ballot Have your say! VOTE your way! November 3, 2020, Consolidated General Election To ensure that San Franciscans can exercise their right to vote in a safe manner during the November 3 election, the Department of Elections will mail ballots to all registered voters in October. Be sure to return your voted ballot on time! See page 5 for more information. Las boletas oficiales, boletas de muestra y otros materiales electorales están disponibles en español. Para más información, visite la página Asistencia en español. 選務處提供中文版正式選票、選票樣本和其他選舉資料。欲知詳情,請查閱「中文選民服務」。 Makakukuha ng opisyal na mga balota, halimbawang mga balota at iba pang mga materyales para sa eleksyon sa Filipino. Para sa impormasyon, tingnan ang pahinang Tulong sa Filipino. -

Public Comment for 5/11/21 Meeting

5/10/2021 SFCTA Mail - Fwd: [email protected] Britney Milton <[email protected]> Fwd: [email protected] 1 message SFCTA Info <[email protected]> Mon, May 10, 2021 at 8:29 AM To: Clerk <[email protected]> San Francisco County Transportation Authority Office: 415-522-4800 [email protected] sfcta.org | sign up for our newsletter ---------- Forwarded message --------- From: Molly Beyer <[email protected]> Date: Sun, May 9, 2021 at 3:33 PM Subject: [email protected] To: [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]>, [email protected] <[email protected]> Subject Heading - Public Comment for 5/11/21 Meeting. Dear Policy Makers – I do NOT support JFK closure. Please consider ALL San Franciscans before closing off free and accessible parking to the de Young (the City’s museum) in favor of petitions from predominately white and upper income bike riders and walkers.