Heroic Africans Legendary Leaders, Iconic Sculptures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

The Impact of Matriarchal Traditions on the Advancement of Ashanti Women in Ghana Karen Mcgee

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Listening to the Voices: Multi-ethnic Women in School of Education Education 2015 The mpI act of Matriarchal Traditions on the Advancement of Ashanti Women in Ghana Karen McGee Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/listening_to_the_voices Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation McGee, Karen (2015). The mpI act of Matriarchal Traditions on the Advancement of Ashanti Women in Ghana. In Betty Taylor (Eds.), Listening to the Voices: Multi-ethnic Women in Education (p. 1-10). San Francisco, CA: University of San Francisco. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Listening to the Voices: Multi-ethnic Women in Education by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Impact of Matriarchal Traditions on the Advancement of Ashanti Women in Ghana Karen McGee What is the impact of a matriarchal tradition and the tradition of an African queenmothership on the ability of African women to advance in political, educational, and economic spheres in their countries? The Ashanti tribe of the Man people is the largest tribe in Ghana; it is a matrilineal society. A description of the precolonial matriarchal tradition among the Ashanti people of Ghana, an analysis of how the matriarchal concept has evolved in more contemporary governments and political situations in Ghana, and an analysis of the status of women in modern Ghana may provide some insight into the impact of the queenmothership concept. -

MEREDITH MONK and ANN HAMILTON: Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc

The House Foundation for the Arts, Inc. | 260 West Broadway, Suite 2, New York, NY 10013 | Tel: 212.904.1330 Fax: 212.904.1305 | Email: [email protected] Web: www.meredithmonk.org Incorporated in 1971, The House Foundation for the Arts provides production and management services for Meredith Monk, Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble, and The House Company. Meredith Monk, Artistic Director • Olivia Georgia, Executive Director • Amanda Cooper, Company Manager • Melissa Sandor, Development Consultant • Jahna Balk, Development Associate • Peter Sciscioli, Assistant Manager • Jeremy Thal, Bookkeeper Press representative: Ellen Jacobs Associates | Tel: 212.245.5100 • Fax: 212.397.1102 Exclusive U.S. Tour Representation: Rena Shagan Associates, Inc. | Tel: 212.873.9700 • Fax: 212.873.1708 • www.shaganarts.com International Booking: Thérèse Barbanel, Artsceniques | [email protected] impermanence(recorded on ECM New Series) and other Meredith Monk & Vocal Ensemble albums are available at www.meredithmonk.org MEREDITH MONK/The House Foundation for the Arts Board of Trustees: Linda Golding, Chair and President • Meredith Monk, Artistic Director • Arbie R. Thalacker, Treasurer • Linda R. Safran • Haruno Arai, Secretary • Barbara G. Sahlman • Cathy Appel • Carol Schuster • Robert Grimm • Gail Sinai • Sali Ann Kriegsman • Frederieke Sanders Taylor • Micki Wesson, President Emerita MEREDITH MONK/The House Foundation for the Arts is made possible, in part, with public and private funds from: MEREDITH MONK AND ANN HAMILTON: Aaron Copland Fund for -

11010329.Pdf

THE RISE, CONSOLIDATION AND DISINTEGRATION OF DLAMINI POWER IN SWAZILAND BETWEEN 1820 AND 1889. A study in the relationship of foreign affairs to internal political development. Philip Lewis Bonner. ProQuest Number: 11010329 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010329 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The Swazi kingdom grew out of the pressures associated with competition for trade and for the rich resources of Shiselweni. While centred on this area it acquired some of its characteristic features - notably a regimental system, and the dominance of a Dlamini aristocracy. Around 1815 the Swazi came under pressure from the South, and were forced to colonise the land lying north of the Lusutfu. Here they remained for some years a nation under arms, as they plundered local peoples, and were themselves swept about by the currents of the Mfecane. In time a more settled administration emerged, as the aristocracy spread out from the royal centres at Ezulwini, and this process accelerated under Mswati as he subdued recalcitrant chiefdoms, and restructured the regiments. -

Jazz Quartess Songlist Pop, Motown & Blues

JAZZ QUARTESS SONGLIST POP, MOTOWN & BLUES One Hundred Years A Thousand Years Overjoyed Ain't No Mountain High Enough Runaround Ain’t That Peculiar Same Old Song Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Sexual Healing B.B. King Medley Signed, Sealed, Delivered Boogie On Reggae Woman Soul Man Build Me Up Buttercup Stop In The Name Of Love Chasing Cars Stormy Monday Clocks Summer In The City Could It Be I’m Fallin’ In Love? Superstition Cruisin’ Sweet Home Chicago Dancing In The Streets Tears Of A Clown Everlasting Love (This Will Be) Time After Time Get Ready Saturday in the Park Gimme One Reason Signed, Sealed, Delivered Green Onions The Scientist Groovin' Up On The Roof Heard It Through The Grapevine Under The Boardwalk Hey, Bartender The Way You Do The Things You Do Hold On, I'm Coming Viva La Vida How Sweet It Is Waste Hungry Like the Wolf What's Going On? Count on Me When Love Comes To Town Dancing in the Moonlight Workin’ My Way Back To You Every Breath You Take You’re All I Need . Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic You’ve Got a Friend Everything Fire and Rain CONTEMPORARY BALLADS Get Lucky A Simple Song Hey, Soul Sister After All How Sweet It Is All I Do Human Nature All My Life I Believe All In Love Is Fair I Can’t Help It All The Man I Need I Can't Help Myself Always & Forever I Feel Good Amazed I Was Made To Love Her And I Love Her I Saw Her Standing There Baby, Come To Me I Wish Back To One If I Ain’t Got You Beautiful In My Eyes If You Really Love Me Beauty And The Beast I’ll Be Around Because You Love Me I’ll Take You There Betcha By Golly -

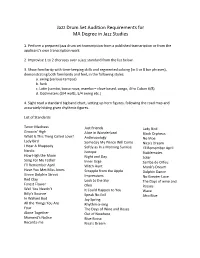

Jazz Drum Set Audition Requirements for MA Degree in Jazz Studies

Jazz Drum Set Audition Requirements for MA Degree in Jazz Studies 1. Perform a prepared jazz drum set transcription from a published transcription or from the applicant’s own transcription work. 2. Improvise 1 to 2 choruses over a jazz standard from the list below. 3. Show familiarity with time-keeping skills and segmented soloing (in 4 or 8 bar phrases), demonstrating both familiarity and feel, in the following styles: a. swing (various tempos) b. funk c. Latin (samba, bossa nova, mambo – clave based, songo, Afro Cuban 6/8) d. Odd meters (3/4 waltz, 5/4 swing etc.) 4. Sight read a standard big band chart, setting up horn figures, following the road map and accurately hitting given rhythmic figures. List of Standards Tenor Madness Just Friends Lady Bird Groovin’ High Alice In Wonderland Black Orpheus What Is This Thing Called Love? Anthropology No Moe Lady Bird Someday My Prince Will Come Nica’s Dream I Hear A Rhapsody Softly as In a Morning Sunrise I’ll Remember April Nardis Isotope Stablemates How High the Moon Night and Day Solar Song For My Father Inner Urge Samba de Orfeu I’ll Remember April Witch Hunt Monk’s Dream Have You Met Miss Jones Scrapple from the Apple Dolphin Dance Green Dolphin Street Impressions No Greater Love Red Clay Look to the Sky The Days of wine and Forest Flower Oleo Rosses Well You Needn’t It Could Happen to You Wave Billy’s Bounce Speak No Evil Afro Blue In Walked Bud Joy Spring All the Things You Are Rhythm-a-ning Four The Days of Wine and Roses Alone Together Out of Nowhere Moment’s Notice Blue Bossa Recorda-me Nica’s Dream . -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

Ascension Heights Subdivision Project

FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT Ascension Heights Subdivision Project Lead Agency: County of San Mateo Planning and Building Department 455 County Center, 2nd Floor Redwood City, CA 94063 PLN2002-00517 SCH No. 2003102061 November 2009 ASCENSION HEIGHTS SUBDIVISON PROJECT FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT Lead Agency: San Mateo County Planning and Building Department 455 County Center, 2nd Floor Redwood City, CA 94063 Contact: James A. Castañeda, Planner II (650) 363-1853 [email protected] Environmental Consultant: Christopher A. Joseph & Associates 179 H Street Petaluma, CA 94952 November 2009 This document is prepared on paper with 100% recycled content. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... I-1 A. LOCATION........................................................................................................................... I-1 B. SUMMARY OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT ................................................................... I-1 C. ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW PROCESS......................................................................... I-2 D. USE OF THIS DOCUMENT................................................................................................ I-3 II. RESPONSE TO COMMENTS .........................................................................................................II-1 A. OVERVIEW .........................................................................................................................II-1 -

Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2001 "Soldiers of the Cross": Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith Kent Toby Dollar University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Dollar, Kent Toby, ""Soldiers of the Cross": Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2001. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3237 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kent Toby Dollar entitled ""Soldiers of the Cross": Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. Stephen V. Ash, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) c.t To the Graduate Council: I am subinitting herewith a dissertation written by Kent TobyDollar entitled '"Soldiers of the Cross': Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy,f with a major in History. -

Young V. Red Clay Consol. Sch. Dist., 122 A.3D 784 (Del

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE REBECCA YOUNG, ELIZABETH H. ) YOUNG and JAMES L. YOUNG, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) C.A. No. 10847-VCL ) RED CLAY CONSOLIDATED ) SCHOOL DISTRICT, ) ) Defendant. ) OPINION Date Submitted: February 23, 2017 Date Decided: May 24, 2017 Richard H. Morse, AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF DELAWARE, Wilmington, Delaware; John W. Shaw, Karen E. Keller, Jeffrey T. Castellano, David M. Fry, Nathan R. Hoeschen, SHAW KELLER LLP. Counsel for Plaintiffs. Barry M. Willoughby, William W. Bowser, Michael P. Stafford, Margaret M. DiBianca, YOUNG CONAWAY STARGATT & TAYLOR, LLP, Wilmington, Delaware. Counsel for Defendant. LASTER, Vice Chancellor. In February 2015, Red Clay Consolidated School District (“Red Clay”) held a special election in which residents were asked to approve an increase in the school-related property taxes paid by owners of non-exempt real estate located within the district (the “Special Election”). Red Clay prevailed in the Special Election, with 6,395 residents voting in favor and 5,515 against. The plaintiffs are residents of Red Clay who did not vote in the Special Election because they were unable to access the polls. They filed suit, asserting that Red Clay violated the provision of the Delaware Constitution which guarantees that “[a]ll elections shall be free and equal.”1 They also contend that Red Clay’s actions violated the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution.2 This court previously held that the plaintiffs’ theories stated claims on which relief could be granted.3 This decision only addresses their state law claim. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana