The Riots in Ferguson, Missouri As a Sequel of the Movie 'The Purge'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discourse, Gender, and the Orient in Zack Snyder's

“THIS IS SPARTA!” DISCOURSE, GENDER, AND THE ORIENT IN ZACK SNYDER’S 300 Jeroen Lauwers, Marieke Dhont and Xanne Huybrecht Zack Snyder’s 2006 film 300, which is based on Frank Miller’s 1998 graphic novel,1 tells the heroic story of the Spartan king Leonidas and his three hundred men. Because Leonidas is forbidden by the oracle and her priests from leading the Spartan army against the mighty Persian god-king Xerxes, he decides to head north himself with a “personal bodyguard” of three hundred of his finest men. This relatively small number of soldiers, joined by an auxiliary Arcadian force, holds the countless number of Persian soldiers back for no fewer than three days. Meanwhile in Sparta, Queen Gorgo works to have the Spartans send additional men to Thermopylae to rescue her husband and his Three Hundred, but her efforts are thwarted by the treason of the politician Theron.2 Ever since the movie’s release, critical and popular opinions have advanced many different perspectives. A rather large number of people have found diverse reasons for considering 300 offensive. One aspect of this critique revolves around its so-called homophobia,3 for example, in the scene in which Leonidas arrogantly calls the Athenians “those phi- losophers and boy-lovers.” Others vituperate the movie for its supposed fascist ideals, pointing out uncanny parallels between the Spartan society and the “Third Reich”: the extreme nationalism, the mutual equality of the Spartiates and their superiority to the helots, the (primitive) genetic selec- tion, and considering women as breeding machines for an ideal fighting 1 The movie quite strictly follows the design and the perspective of the graphic novel. -

Filozofická Fakulta Univerzity Palackého V Olomouci

FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA UNIVERZITY PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI KATEDRA SLAVISTIKY RUSKÁ KLASICKÁ LITERATURA OČIMA ZAHRANIČNÍCH FILMAŘŮ (NA PŘÍKLADU ROMÁNU A. S. PUŠKINA „EVŽEN ONĚGIN“ A FILMU „ONĚGIN“) CLASSIC RUSSIAN LITERATURE THROUGH THE EYES OF FOREIGN FILM PRODUCERS (FOR EXAMPLE: NOVEL OF A. S. PUSKIN „EUGENE ONEGIN“ AND THE MOVIE „ONEGIN“) Bakalářská práce Vypracovala: Dita Marešová Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jekatěrina Mikešová, Ph.D. OLOMOUC 2014 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla všechny použité prameny. V Olomouci, 10. 4. 2013 Dita Marešová Poděkování Děkuji Mgr. Jekatěrině Mikešové, Ph.D. za konzultace, rady a připomínky, které mi během psaní bakalářské práce poskytla. Obsah ÚVOD ................................................................................................................................. 5 1. FILM A ROMÁN ........................................................................................................ 7 1.1. JAZYK FILMU.................................................................................................... 8 1.1.1. JAZYK FILMU ONĚGIN ................................................................................ 9 1.1.2. VÝZNAM FILMU ONĚGIN ........................................................................... 9 2. O FILMU ONĚGIN (1999) ....................................................................................... 11 2.2. FILMOVÁ LOKACE ........................................................................................ 13 2.2.1. EXTERIÉRY A INTERIÉRY ................................................................... -

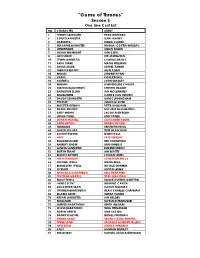

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar

Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar Hate Speech Ignited Understanding Hate Speech in Myanmar October 2020 About Us This report was written based on the information and data collection, monitoring, analytical insights and experiences with hate speech by civil society organizations working to reduce and/or directly af- fected by hate speech. The research for the report was coordinated by Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) and Progressive Voice and written with the assistance of the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School while it is co-authored by a total 19 organizations. Jointly published by: 1. Action Committee for Democracy Development 2. Athan (Freedom of Expression Activist Organization) 3. Burma Monitor (Research and Monitoring) 4. Generation Wave 5. International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School 6. Kachin Women’s Association Thailand 7. Karen Human Rights Group 8. Mandalay Community Center 9. Myanmar Cultural Research Society 10. Myanmar People Alliance (Shan State) 11. Nyan Lynn Thit Analytica 12. Olive Organization 13. Pace on Peaceful Pluralism 14. Pon Yate 15. Progressive Voice 16. Reliable Organization 17. Synergy - Social Harmony Organization 18. Ta’ang Women’s Organization 19. Thint Myat Lo Thu Myar (Peace Seekers and Multiculturalist Movement) Contact Information Progressive Voice [email protected] www.progressivevoicemyanmar.org Burma Monitor [email protected] International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School [email protected] https://hrp.law.harvard.edu Acknowledgments Firstly and most importantly, we would like to express our deepest appreciation to the activists, human rights defenders, civil society organizations, and commu- nity-based organizations that provided their valuable time, information, data, in- sights, and analysis for this report. -

Stalin's Purge and Its Impact on Russian Families a Pilot Study

25 Stalin's Purge and Its Impact on Russian Families A Pilot Study KATHARINE G. BAKER and JULIA B. GIPPENREITER INTRODUCTION This chapter describes a preliminary research project jointly undertaken during the winter of 1993-1994 by a Russian psychologist and an American social worker. The authors first met during KGB's presentation of Bowen Family Systems Theory (BFST) at Moscow State Uni versity in 1989. During frequent meetings in subsequent years in the United States and Russia, the authors shared their thoughts about the enormous political and societal upheaval occurring in Russia in the 1990s. The wider context of Russian history in the 20th-century and its impact on contemporary events, on the functioning of families over several generations, and on the functioning of individuals living through turbulent times was central to these discussions. How did the prolonged societal nightmare of the 1920s and the 1930s affect the popula tion of the Soviet Union? What was the impact of the demented paranoia of those years of to talitarian repression on innocent citizens who tried to live "normal" lives, raise families, go to work, stay healthy, and live out their lives in peace? What was the emotional legacy of Stalin's Purge of 1937-1939 for the children and grandchildren of its victims? Does it continue to have an impact on the functioning of modern-day Russians who are struggling with new societal disruptions during the post-Communist transition to a free-market democracy? These are the questions that led to the research study presented -

From Hashtag to Hate Crime: Twitter and Anti-Minority Sentiment ∗

From Hashtag to Hate Crime: Twitter and Anti-Minority Sentiment ∗ Karsten M¨uller† and Carlo Schwarz‡ October 31, 2019 Abstract We study whether social media can activate hatred of minorities, with a focus on Donald Trump’s political rise. We show that the increase in anti-Muslim sentiment in the US since the start of Trump’s presidential campaign has been concentrated in counties with high Twitter usage. To establish causality, we develop an identification strategy based on Twitter’s early adopters at the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival, which marked a turning point in the site’s popularity. Instrumenting with the locations of SXSW followers in March 2007, while controlling for the locations of SXSW followers who joined in previous months, we find that a one standard deviation increase in Twitter usage is associated with a 38% larger increase in anti-Muslim hate crimes since Trump’s campaign start. We also show that Trump’s tweets about Islam-related topics are highly correlated with anti-Muslim hate crimes after the start of his presidential campaign, but not before. These correlations persist in an instrumental variable framework exploiting that Trump is more likely to tweet about Muslims on days when he plays golf. Trump’s tweets also predict more anti-Muslim Twitter activity of his followers and higher cable news attention paid to Muslims, particularly on Fox News. ∗A previous version of this paper was circulated under the title “Making America Hate Again? Twitter and Hate Crime Under Trump.” We are grateful to Roland B´enabou, -

Aesthetic Violence: the Victimisation of Women in the Quebec Novel

AESTHETIC VIOLENCE: THE VICTIMISATION OF WOMEN IN THE QUEBEC NOVEL by JANE LUCINDA TILLEY B.A.(Hons), The University of Southampton, U.K., 1987 M.A., The University of British Columbia, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITI’ED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of French) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA June 1995 Jane Lucinda Tilley, 1995 ___________ In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Bntish Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date 22 ‘( (c/s_ DE-6 (2188) 11 Abstract The latent (androcentric) eroticism of rape has been exploited in Western culture, from mythology through to a contemporary entertainment industry founded on a cultural predilection for the representation of violence against women. In literature the figure of Woman as Victim has evolved according to shifting fashions and (male) desires until, in contemporary avant-garde writings, themes of sexual violence perform an intrinsic role in sophisticated textual praxis, Woman’s body becoming the playground for male artistic expression and textual experimentation. -

OAG Hate Crime Rpt for 1/96

HATE CRIMES IN FLORIDA January 1, 2001 - December 31, 2001 Office of Attorney General Bob Butterworth Table of Contents Letter from Attorney General Bob Butterworth ........................................ Introduction ................................................................... Executive Summary ........................................................... 1 Annual Report, Hate Crimes in Florida January 1 - December 31, 2001 What is A Hate Crime? ............................................ 2 Types of Offenses Offense Totals by Motivation Type January 1 - December 31, 2001 ...................................... 2 Crimes Against Persons (1991 - 2001) ....................................... 3 Crimes Against Persons vs. Crimes Against Property...................................................... 4 2001 Florida Hate Crimes Overview by Motivation Type ......................... 4 Hate Crimes Comparison by Motivation (1991 - 2001) .......................... 4 Offense Totals by County and Agency January 1 - December 31, 2001 .......................................... 5 Hate Crimes by Offenses and Motivation Type by County and Agency January 1 - December 31, 2001 ......................................... 11 Appendices Appendix 1 - Hate Crimes Reporting ....................................... 25 Appendix 2 - Florida Hate Crimes Statutes ................................................................. .. 32 Appendix 3 - Florida Attorney General’s Office of Civil Rights .................... 33 Appendix 4 - Sources of Additional Information -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5fv121wm Author Stroud, Martha Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia by Martha Stroud A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair Professor Laura Nader Professor Sharon Kaufman Professor Jeffrey A. Hadler Spring 2015 “Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia” © 2015 Martha Stroud 1 Abstract Ripples, Echoes, and Reverberations: 1965 and Now in Indonesia by Martha Stroud Joint Doctor of Philosophy with University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Chair In Indonesia, during six months in 1965-1966, between half a million and a million people were killed during a purge of suspected Communist Party members after a purported failed coup d’état blamed on the Communist Party. Hundreds of thousands of Indonesians were imprisoned without trial, many for more than a decade. The regime that orchestrated the mass killings and detentions remained in power for over 30 years, suppressing public discussion of these events. It was not until 1998 that Indonesians were finally “free” to discuss this tragic chapter of Indonesian history. In this dissertation, I investigate how Indonesians perceive and describe the relationship between the past and the present when it comes to the events of 1965-1966 and their aftermath. -

Written Testimony of NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc

New York Office Washington, D.C. Office th 40 Rector Street, 5th Floor 700 14 Street, NW, Suite 600 Washington, D.C. 20005 New York, NY 10006-1738 T. (212) 965 2200 F. (212) 226 7592 T. (202) 682 1300 F. (202) 682 1312 www.naacpldf.org June 29, 2021 Submitted electronically Ad Hoc Committee – State Election Commission House Legislative Oversight Committee South Carolina House of Representatives 110 Blatt Building Columbia, SC 29201 [email protected] Re: Civil Rights Considerations for Maintaining Voter Rolls Dear Chair Newtown and Committee Members: The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (“LDF”) thanks the Ad Hoc Committee – State Election Commission for the opportunity to submit this written testimony regarding the maintenance of voter rolls. As a nonprofit, nonpartisan civil-rights organization, our objective in doing so is to ensure that all voters in South Carolina, particularly Black voters and other voters of color, enjoy full, meaningful, and unburdened access to the fundamental right to vote, including the ability to register to vote and remain registered. The United States Supreme Court has long described the right to vote as a fundamental right, because it is preservative of all other rights.1 Voting is “the citizen’s link to his laws and government”2 and “the essence of a democratic society.”3 If the right to vote is undermined, other rights “are illusory.”4 Thus, in a democracy, safeguarding the right to vote “is a fundamental matter.”5 Because only those South Carolinians who are registered to vote may participate in an election,6 actions undertaken by a state or local authority to remove voters from registration lists, if flawed or inaccurate, can be a harmful means of preventing eligible citizens from accessing the franchise.7 For decades after the end of Reconstruction, South Carolina and other Southern states used 1 See Yick Wo v. -

233 David R. Shearer and Vladimir Khaustov Stalin and the Lubianka

Book Reviews 233 David R. Shearer and Vladimir Khaustov Stalin and the Lubianka: A Documentary History of the Political Police and Security Organs in the Soviet Union, 1922–1953 (New Haven, ct: Yale University Press, 2015), 392 pp., $85.00 (hb), isbn 9780300171891. Stalin and the Lubianka has appeared in Yale University Press’ Annals of Communism Series, presenting selected, formerly unavailable documents concerning Soviet history. It was prepared and the commentaries were written by David R. Shearer and Vladimir Khaustov, Shearer being Professor of Soviet history at the University of Delaware and author of the excellent study Policing Stalin’s Socialism (2009), and Khaustov Professor at the Federal Security Service Academy of Russia. As the title suggests, it is a documentary history rather than just a volume of 177 documents, drawn from different archival sources, including those of the Russian Presidential Archive and the archive of the Russian state security service. Most of them have been selected from a much broader collection, the 4-volume Russian-language series Lubianka, Stalin (Moscow, 2003–2007), with Khaustov as one of the editors. It is a book about the relationship of the Communist Party Secretary General Joseph Stalin and the powerful institution with its many succeeding names (Cheka, ogpu, nkvd, nkgb, mgb, etc.) that had its headquarters at Lubianka Square in the centre of Moscow. Although it remained essentially the same organization, the authors convincingly argue that it went through considerable successive changes. Created on December 20, 1917 as a temporary agency in the exigencies of a brutal revolutionary war, originally it functioned as just a political police, perse- cuting (perceived) enemies. -

Voter Suppression Post-<I>Shelby</I>

Mercer Law Review Volume 71 Number 3 Lead Articles Edition - Contemporary Article 10 Issues in Election Law 5-2020 Voter Suppression Post-Shelby: Impacts and Issues of Voter Purge and Voter ID Laws Lydia Hardy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.mercer.edu/jour_mlr Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation Lydia Hardy, Comment, Voter Suppression Post-Shelby: Impacts and Issues of Voter Purge and Voter ID Laws, 71 Mercer L. Rev. 857 (2020) This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Mercer Law School Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mercer Law Review by an authorized editor of Mercer Law School Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [7] POST-SHELBY (EDITS INCORPORATED) (DO NOT DELETE) 4/13/2020 10:52 AM Voter Suppression Post-Shelby: Impacts and Issues of Voter Purge and Voter ID Laws* I. INTRODUCTION The old adage that history repeats itself is no truer than when considered in the context of contemporary voting and election law. The history repeating itself within a new wave of legislation is voter suppression that mirrors many issues in the voting rights history of the United States. Since the landmark Shelby County v. Holder1 case in 2013, there has been a marked increase in the passage of new voting laws as well as corresponding court challenges to these laws. Unlike the discriminatory tactics and laws of the Jim Crow era that were banned and declared unconstitutional after the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,2 contemporary voter suppression has taken on a more subversive and facially neutral quality.