The Development of Public Sector Audit Independence: the Colonial Experience in Western Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Administering Justice for the Community for 150 Years

The Supreme Court of Western Australia 1861 - 2011 Administering Justice for the Community for 150 years by The Honourable Wayne Martin Chief Justice of Western Australia Ceremonial Sitting - Court No 1 17 June 2011 Ceremonial Sitting - Administering Justice for the Community for 150 Years The court sits today to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the creation of the court. We do so one day prematurely, as the ordinance creating the court was promulgated on 18 June 1861, but today is the closest sitting day to the anniversary, which will be marked by a dinner to be held at Government House tomorrow evening. Welcome I would particularly like to welcome our many distinguished guests, the Rt Hon Dame Sian Elias GNZM, Chief Justice of New Zealand, the Hon Terry Higgins AO, Chief Justice of the ACT, the Hon Justice Geoffrey Nettle representing the Supreme Court of Victoria, the Hon Justice Roslyn Atkinson representing the Supreme Court of Queensland, Mr Malcolm McCusker AO, the Governor Designate, the Hon Justice Stephen Thackray, Chief Judge of the Family Court of WA, His Honour Judge Peter Martino, Chief Judge of the District Court, President Denis Reynolds of the Children's Court, the Hon Justice Neil McKerracher of the Federal Court of Australia and many other distinguished guests too numerous to mention. The Chief Justice of Australia, the Hon Robert French AC had planned to join us, but those plans have been thwarted by a cloud of volcanic ash. We are, however, very pleased that Her Honour Val French is able to join us. I should also mention that the Chief Justice of New South Wales, the Hon Tom Bathurst, is unable to be present this afternoon, but will be attending the commemorative dinner to be held tomorrow evening. -

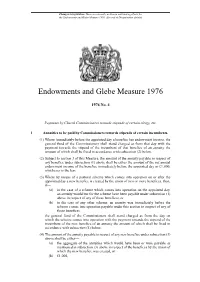

Endowments and Glebe Measure 1976

Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Endowments and Glebe Measure 1976. (See end of Document for details) Endowments and Glebe Measure 1976 1976 No. 4 Payments by Church Commissioners towards stipends of certain clergy, etc. 1 Annuities to be paid by Commissioners towards stipends of certain incumbents. (1) Where immediately before the appointed day a benefice has endowment income, the general fund of the Commissioners shall stand charged as from that day with the payment towards the stipend of the incumbent of that benefice of an annuity the amount of which shall be fixed in accordance with subsection (2) below. (2) Subject to section 3 of this Measure, the amount of the annuity payable in respect of any benefice under subsection (1) above shall be either the amount of the net annual endowment income of the benefice immediately before the appointed day or £1,000, whichever is the less. (3) Where by means of a pastoral scheme which comes into operation on or after the appointed day a new benefice is created by the union of two or more benefices, then, if— (a) in the case of a scheme which comes into operation on the appointed day, an annuity would but for the scheme have been payable under subsection (1) above in respect of any of these benefices, or (b) in the case of any other scheme, an annuity was immediately before the scheme comes into operation payable under this section in respect of any of those benefices, the general fund of the Commissioners shall stand charged as from the day on which the scheme comes into operation with the payment towards the stipend of the incumbent of the new benefice of an annuity the amount of which shall be fixed in accordance with subsection (4) below. -

Wellington's Men in Australia

Wellington’s Men in Australia Peninsular War Veterans and the Making of Empire c. 1820–40 Christine Wright War, Culture and Society, 1750 –1850 War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Editors: Rafe Blaufarb (Tallahassee, USA), Alan Forrest (York, UK), and Karen Hagemann (Chapel Hill, USA) Editorial Board: Michael Broers (Oxford UK), Christopher Bayly (Cambridge, UK), Richard Bessel (York, UK), Sarah Chambers (Minneapolis, USA), Laurent Dubois (Durham, USA), Etienne François (Berlin, Germany), Janet Hartley (London, UK), Wayne Lee (Chapel Hill, USA), Jane Rendall (York, UK), Reinhard Stauber (Klagenfurt, Austria) Titles include: Richard Bessel, Nicholas Guyatt and Jane Rendall (editors) WAR, EMPIRE AND SLAVERY, 1770–1830 Alan Forrest and Peter H. Wilson (editors) THE BEE AND THE EAGLE Napoleonic France and the End of the Holy Roman Empire, 1806 Alan Forrest, Karen Hagemann and Jane Rendall (editors) SOLDIERS, CITIZENS AND CIVILIANS Experiences and Perceptions of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1790–1820 Karen Hagemann, Gisela Mettele and Jane Rendall (editors) GENDER, WAR AND POLITICS Transatlantic Perspectives, 1755–1830 Marie-Cécile Thoral FROM VALMY TO WATERLOO France at War, 1792–1815 Forthcoming Michael Broers, Agustin Guimera and Peter Hick (editors) THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE AND THE NEW EUROPEAN POLITICAL CULTURE Alan Forrest, Etienne François and Karen Hagemann (editors) WAR MEMORIES The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Europe Leighton S. James WITNESSING WAR Experience, Narrative and Identity in German Central Europe, 1792–1815 Catriona Kennedy NARRATIVES OF WAR Military and Civilian Experience in Britain and Ireland, 1793–1815 Kevin Linch BRITAIN AND WELLINGTON’S ARMY Recruitment, Society and Tradition, 1807–1815 War, Culture and Society, 1750–1850 Series Standing Order ISBN 978–0–230–54532–8 hardback 978–0–230–54533–5 paperback (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

Swamp : Walking the Wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2012 Swamp : walking the wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain ; and with the exegesis, A walk in the anthropocene: homesickness and the walker-writer Anandashila Saraswati Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation Saraswati, A. (2012). Swamp : walking the wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain ; and with the exegesis, A walk in the anthropocene: homesickness and the walker-writer. Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/588 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/588 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. USE OF THESIS This copy is the property of Edith Cowan University. However, the literary rights of the author must also be respected. If any passage from this thesis is quoted or closely paraphrased in a paper of written work prepared by the user, the source of the passage must be acknowledged in the work. -

By-Elections in Western Australia

By-elections in Western Australia Contents WA By-elections - by date ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 WA By-elections - by reason ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 14 By-elections due to the death of a sitting member ........................................................................................................................................................... 14 Ministerial by-elections.................................................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Fresh election ordered ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Seats declared vacant ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 WA By-elections - by electorate .......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

LAND REGISTRATION for the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY a Conveyancing Revolution

LAND REGISTRATION FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY A Conveyancing Revolution LAND REGISTRATION BILL AND COMMENTARY Laid before Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 9 July 2001 LAW COMMISSION H M LAND REGISTRY LAW COM NO 271 LONDON: The Stationery Office HC 114 The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. THE COMMISSIONERS ARE: The Honourable Mr Justice Carnwath CVO, Chairman Professor Hugh Beale Mr Stuart Bridge· Professor Martin Partington Judge Alan Wilkie QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers Her Majesty’s Land Registry, a separate department of government and now an Executive Agency, maintains the land registers for England and Wales and is responsible for delivering all land registration services under the Land Registration Act 1925. The Chief Land Registrar and Chief Executive is Mr Peter Collis The Solicitor to H M Land Registry is Mr Christopher West The terms of this report were agreed on 31 May 2001. The text of this report is available on the Internet at: http://www.lawcom.gov.uk · Mr Stuart Bridge was appointed Law Commissioner with effect from 2 July 2001. The terms of this report were agreed on 31 May 2001, while Mr Charles Harpum was a Law Commissioner. ii LAW COMMISSION HM LAND REGISTRY LAND REGISTRATION FOR THE TWENTY- FIRST CENTURY A Conveyancing Revolution CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: THE LAND REGISTRATION BILL AND -

Images of the Caribbean : Materials Development on a Pluralistic Society

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1982 Images of the Caribbean : materials development on a pluralistic society. Gloria. Gordon University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Gordon, Gloria., "Images of the Caribbean : materials development on a pluralistic society." (1982). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2245. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2245 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OP THE CARIBBEAN - MATERIALS DEVELOPMENT ON A PLURALISTIC SOCIETY A Dissertation Presented by Gloria Mark Gordon Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 1 982 School of Education © 1982 GLORIA MARK GORDON All Rights Reserved IMAGES OF THE CARIBBEAN - MATERIALS DEVELOPMENT ON A PLURALISTIC SOCIETY A Dissertation Presented by Gloria Mark Gordon Approved as to style and content by: Georg? E. Urch, Chairperson ) •. aJb...; JL Raljih Faulkinghairi, Member u l i L*~- Mario FanbfLni , Dean School of (Education This work is dedicated to my daughter Yma, my sisters Carol and Shirley, my brother Ainsley, my great aunt Virginia Davis, my friend and mentor Wilfred Cartey and in memory of my parents Albert and Thelma Mark iii . ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work owes much, to friends and colleagues who provided many elusive forms of sustenance: Ivy Evans, Joan Sandler, Elsie Walters, Ellen Mulato, Nana Seshibe, Hilda Kokuhirwa, Colden Murchinson, Sibeso Mokub. -

Spotlight On

1 September-October 2000 No. 249 Official Newsletter of The Library and Information Service of Western Australia Spotlight on.... - Y o u r G u i d e t o K n o w l e d g e state reference library state2 Welcome to the referenceWelcome library state reference second special edition to the State Reference Library of knowit. This issue library state reference library state focuses on the State Reference Library referenceCultural monuments library such as services as well as museums, art galleries and state statelibraries are allreference too often seen as LYNN including the second issue of the libraryan obligation rather thanstate a means Professional Journal. to a cultural end. I’m happy to report the reference library State Records Bill This issue of knowit celebrates the stateState Referencereference Library of Lynn Allen (CEO and State Librarian) (1999) is passing FROM Western Australia. through Parliament having had its second reading library state Claire Forte in the Upper House. We are all looking forward to (Director: State Reference Library) The State Reference Library this world leading legislation being proclaimed. reference library covers the full range of classifiable written knowledge in much the same way as a public library. As you I hope many of you will be able to visit the Centre state reference library state might expect in a large, non-circulating library, the line line line for the Book on the Ground Floor of the Alexander line line referencebreadth of material library on the shelves state is extensive. reference Library Building to view the current exhibition Quokkas to Quasars - A Science Story which library state reference library state A We also have specialist areas such as business, film highlights the special achievements of 20 Western and video, music, newspapers, maps, family history Australian scientists. -

Statute Law (Repeals) Measure

Statute Law (Repeals) Measure A Measure passed by the General Synod of the Church of England, laid before both Houses of Parliament pursuant to the Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act 1919. Ordered by The House of Lords to be printed 14th March 2018 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 14th March 2018 HL Paper 92 57/1 HC 781 Statute Law (Repeals) Measure CONTENTS 1 Repeals 2 Short title, commencement and extent Schedule — Repeals Part 1 — Clergy Part 2 — Benefices Part 3 — Ecclesiastical Property Part 4 — Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction and Fees Part 5 — Church Representation Part 6 — Services Part 7 — Church Commissioners Part 8 — Education, &c. Part 9 — Cathedrals HL Paper 92 57/1 Statute Law (Repeals) Measure 1 A Measure to repeal certain enactments of ecclesiastical law which (except in so far as their effect is preserved) are no longer of practical utility. 1 Repeals The enactments specified in the Schedule are repealed or revoked to the extent specified in the second column of that Schedule. 2 Short title, commencement and extent (1) This Measure may be cited as the Statute Law (Repeals) Measure 2018. 5 (2) This section comes into force on the day on which this Measure is passed. (3) Section 1 and the Schedule come into force on such day as the Archbishops of Canterbury and York may by order jointly appoint; and different days may be appointed for different purposes. (4) The Archbishops of Canterbury and York may by order jointly make 10 transitional, transitory or saving provision in connection with the commencement of a provision of the Schedule. -

Fourteenth Report: Draft Statute Law Repeals Bill

The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 211) (SCOT. LAW COM. No. 140) STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL Presented to Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor and the Lord Advocate by Command of Her Majesty April 1993 LONDON: HMSO E17.85 net Cm 2176 The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the Law. The Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Brooke, Chairman Mr Trevor M. Aldridge, Q.C. Mr Jack Beatson Mr Richard Buxton, Q.C. Professor Brenda Hoggett, Q.C. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Collon. Its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WClN 2BQ. The Scottish Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Lord Davidson, Chairman .. Dr E.M. Clive Professor P.N. Love, C.B.E. Sheriff I.D.Macphail, Q.C. Mr W.A. Nimmo Smith, Q.C. The Secretary of the Scottish Law Commission is Mr K.F. Barclay. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR. .. 11 THE LAW COMMISSION AND THE SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill To the Right Honourable the Lord Mackay of Clashfern, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and the Right Honourable the Lord Rodger of Earlsferry, Q.C., Her Majesty's Advocate. In pursuance of section 3(l)(d) of the Law Commissions Act 1965, we have prepared the draft Bill which is Appendix 1 and recommend that effect be given to the proposals contained in it. -

“A Veritable Augustus”: the Life of John Winthrop Hackett, Newspaper

“A Veritable Augustus”: The Life of John Winthrop Hackett, Newspaper Proprietor, Politician and Philanthropist (1848-1916) by Alexander Collins B.A., Grad.Dip.Loc.Hist., MSc. Presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University March 2007 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not been previously submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ……………………….. Alexander Collins ABSTRACT Irish-born Sir John Winthrop Hackett was a man of restless energy who achieved substantial political authority and social standing by means of the power gained through his editorship and part-ownership of the West Australian newspaper and his position in parliament. He was a man with a mission who intended to be a successful businessman, sought to provide a range of cultural facilities and, finally, was the moving force in establishing a tertiary educational institution for the people of Western Australia. This thesis will argue that whatever Hackett attempted to achieve in Western Australia, his philosophy can be attributed to his Irish Protestant background including his student days at Trinity College Dublin. After arriving in Australia in 1875 and teaching at Trinity College Melbourne until 1882, his ambitions took him to Western Australia where he aspired to be accepted and recognised by the local establishment. He was determined that his achievements would not only be acknowledged by his contemporaries, but also just as importantly be remembered in posterity. After a failed attempt to run a sheep station, he found success as part-owner and editor of the West Australian newspaper. -

The Contracting out (Functions Relating to the Royal Parks) Order 2016

Draft Order laid before Parliament under section 77(2) of the Deregulation and Contracting Out Act 1994, for approval by resolution of each House of Parliament. DRAFT STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2016 No. 0000 CONTRACTING OUT, ENGLAND The Contracting Out (Functions relating to the Royal Parks) Order 2016 Made - - - - *** Coming into force in accordance with article 1(c) The Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred by sections 69(2) and (4) of the Deregulation and Contracting Out Act 1994(a), makes the following Order. A draft of this Order was laid before Parliament in accordance with section 77(2) of the Deregulation and Contracting Out Act 1994 and approved by a resolution of each House. Citation, extent, application and commencement 1. This Order— (a) may be cited as the Contracting Out (Functions relating to the Royal Parks) Order 2016; (b) extends to England and Wales; and (c) comes into force on the day after the day on which it is made. Interpretation 2. In this Order “the functions” means the functions now vested in the Secretary of State, and referred to in the following provisions— (a) section 22 of the Crown Lands Act 1851 (duties of Commissioners of Woods, &c. in relation to Royal Parks, &c., and under the Acts in Schedule, vested in Commissioners of Works)( b), in relation to— (i) Saint James’s Park; (ii) Hyde Park; (iii) Green Park; (a) 1994 c.40. (b) 1851 c.42 (14 & 15 Vict). Section 22 was amended by section 1 of and the Schedule to the Statute Law Revision Act 1892 (55 & 56 Vict c.19) and section 1 of and the Schedule to the Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1993 (c.50).