14 Models of Unemployment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Unemployment Structural Or Cyclical? Main Features of Job Matching in the EU After the Crisis

IZA Policy Paper No. 91 Is Unemployment Structural or Cyclical? Main Features of Job Matching in the EU after the Crisis Alfonso Arpaia Aron Kiss Alessandro Turrini P O L I C Y P A P E R S I E S P A P Y I C O L P September 2014 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Is Unemployment Structural or Cyclical? Main Features of Job Matching in the EU after the Crisis Alfonso Arpaia European Commission, DG ECFIN and IZA Aron Kiss European Commission, DG ECFIN Alessandro Turrini European Commission, DG ECFIN and IZA Policy Paper No. 91 September 2014 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] The IZA Policy Paper Series publishes work by IZA staff and network members with immediate relevance for policymakers. Any opinions and views on policy expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of IZA. The papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the corresponding author. IZA Policy Paper No. 91 September 2014 ABSTRACT Is Unemployment Structural or Cyclical? * Main Features of Job Matching in the EU after the Crisis The paper sheds light on developments in labour market matching in the EU after the crisis. First, it analyses the main features of the Beveridge curve and frictional unemployment in EU countries, with a view to isolate temporary changes in the vacancy-unemployment relationship from structural shifts affecting the efficiency of labour market matching. -

Daniel K Tarullo: Unemployment, the Labor Market, and the Economy

Daniel K Tarullo: Unemployment, the labor market, and the economy Speech by Mr Daniel K Tarullo, Member of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, at the World Leaders Forum, Columbia University, New York, 20 October 2011. * * * I appreciate the opportunity to be at Columbia this evening to discuss the American economy and, in particular, the employment situation.1 Mindful of the trend of public discourse toward hyperbole, I hesitated in deciding whether to characterize that situation as a crisis. But it is hard to justify characterizing in any less urgent fashion the circumstances of the nearly 30 million Americans who are officially unemployed, out of the labor force but wanting jobs, or involuntarily working only part time. This situation reflects acute problems in labor markets, created by the financial crisis and the recession that followed. But we also confront chronic labor market problems. In my remarks this evening, I will outline both sets of problems. In my observations on policy responses, however, I will concentrate on the acute problems – in part to join the debate on their origins, in part because they call for the most immediate response, and in part because they are most relevant to my monetary policy responsibilities as a member of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve. That said, I hope you will not think the chronic problems any less important for the briefer treatment they receive tonight. Most of what I have to say can be summarized in three points. First, the acute problems are largely, though not completely, the result of a shortfall of aggregate demand following the financial crisis and recession. -

Structural Unemployment in Selected Countries

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Alatalo, Johanna et al. Research Report Structural unemployment in selected countries Aktuelle Berichte, No. 4/2015 Provided in Cooperation with: Institute for Employment Research (IAB) Suggested Citation: Alatalo, Johanna et al. (2015) : Structural unemployment in selected countries, Aktuelle Berichte, No. 4/2015, Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB), Nürnberg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/161693 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Current reports Structural Unemployment in Selected Countries 4/2015 What to expect / In aller Kürze This report introduces basics on structural unemployment in some member countries of the International Labour Market Forecasting Network. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern Lima, Gerson P. Macroambiente 3 March 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/63135/ MPRA Paper No. 63135, posted 21 Mar 2015 13:54 UTC Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern Gerson P. Lima1 The present treatise is an attempt to present a modern version of old doctrines with the aid of the new work, and with reference to the new problems, of our own age (Marshall, 1890, Preface to the First Edition). 1. Introduction Many people are convinced that the contemporaneous mainstream economics is not qualified to explaining what is going on, to tame financial markets, to avoid crises and to provide a concrete solution to the poor and deteriorating situation of a large portion of the world population. Many economists, students, newspapers and informed people are asking for and expecting a new economics, a real world economic science. “The Keynes- inspired building-blocks are there. But it is admittedly a long way to go before the whole construction is in place. But the sooner we are intellectually honest and ready to admit that modern neoclassical macroeconomics and its microfoundationalist programme has come to way’s end – the sooner we can redirect our aspirations to more fruitful endeavours” (Syll, 2014, p. 28). Accordingly, this paper demonstrates that current mainstream monetarist economics cannot be science and proposes new approaches to economic theory and econometric method that after replication and enhancement may be a starting point for the creation of the real world economic theory. -

Notes for Econ202a: Consumption

Notes for Econ202A: Consumption Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas UC Berkeley Fall 2014 c Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, 2014, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Disclaimer: These notes are riddled with inconsistencies, typos and omissions. Use at your own peril. 1 Introduction Where the second part of econ202A fits? • Change in focus: the first part of the course focused on the big picture: long run growth, what drives improvements in standards of living. • This part of the course looks more closely at pieces of models. We will focus on four pieces: – consumption-saving. Large part of national output. – investment. Most volatile part of national output. – open economy. Difference between S and I is the current account. – financial markets (and crises). Because we learned the hard way that it matters a lot! 2 Consumption under Certainty 2.1 A Canonical Model A Canonical Model of Consumption under Certainty • A household (of size 1!) lives T periods (from t = 0 to t = T − 1). Lifetime T preferences defined over consumption sequences fctgt=1: T −1 X t U = β u(ct) (1) t=0 where 0 < β < 1 is the discount factor, ct is the household’s consumption in period t and u(c) measures the utility the household derives from consuming ct in period t. u(c) satisfies the ‘usual’ conditions: – u0(c) > 0, – u00(c) < 0, 0 – limc!0 u (c) = 1 0 – limc!1 u (c) = 0 • Seems like a reasonable problem to analyze. 2 2.2 Questioning the Assumptions Yet, this representation of preferences embeds a number of assumptions. Some of these assumptions have some micro-foundations, but to be honest, the main advantage of this representation is its convenience and tractability. -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

A Post-Keynesian Approach As an Alternative to Neoclassical in the Explanation of Monetary and Financial System

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zachariadis, Savvas Article A Post-Keynesian approach as an alternative to neoclassical in the explanation of monetary and financial system Financial Studies Provided in Cooperation with: "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), Romanian Academy Suggested Citation: Zachariadis, Savvas (2020) : A Post-Keynesian approach as an alternative to neoclassical in the explanation of monetary and financial system, Financial Studies, ISSN 2066-6071, Romanian Academy, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, Bucharest, Vol. 24, Iss. 1 (87), pp. 21-35 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/231693 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

Three Dimensions of Classical Utilitarian Economic Thought ––Bentham, J.S

July 2012 Three Dimensions of Classical Utilitarian Economic Thought ––Bentham, J.S. Mill, and Sidgwick–– Daisuke Nakai∗ 1. Utilitarianism in the History of Economic Ideas Utilitarianism is a many-sided conception, in which we can discern various aspects: hedonistic, consequentialistic, aggregation or maximization-oriented, and so forth.1 While we see its impact in several academic fields, such as ethics, economics, and political philosophy, it is often dragged out as a problematic or negative idea. Aside from its essential and imperative nature, one reason might be in the fact that utilitarianism has been only vaguely understood, and has been given different roles, “on the one hand as a theory of personal morality, and on the other as a theory of public choice, or of the criteria applicable to public policy” (Sen and Williams 1982, 1-2). In this context, if we turn our eyes on economics, we can find intimate but subtle connections with utilitarian ideas. In 1938, Samuelson described the formulation of utility analysis in economic theory since Jevons, Menger, and Walras, and the controversies following upon it, as follows: First, there has been a steady tendency toward the removal of moral, utilitarian, welfare connotations from the concept. Secondly, there has been a progressive movement toward the rejection of hedonistic, introspective, psychological elements. These tendencies are evidenced by the names suggested to replace utility and satisfaction––ophélimité, desirability, wantability, etc. (Samuelson 1938) Thus, Samuelson felt the need of “squeezing out of the utility analysis its empirical implications”. In any case, it is somewhat unusual for economists to regard themselves as utilitarians, even if their theories are relying on utility analysis. -

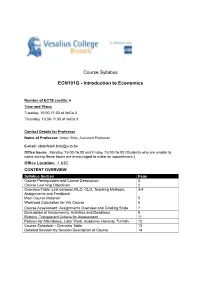

Course Syllabus ECN101G

Course Syllabus ECN101G - Introduction to Economics Number of ECTS credits: 6 Time and Place: Tuesday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Thursday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Contact Details for Professor Name of Professor: Abdel. Bitat, Assistant Professor E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday, 15:00-16:00 and Friday, 15:00-16:00 (Students who are unable to come during these hours are encouraged to make an appointment.) Office Location: -1.63C CONTENT OVERVIEW Syllabus Section Page Course Prerequisites and Course Description 2 Course Learning Objectives 2 Overview Table: Link between MLO, CLO, Teaching Methods, 3-4 Assignments and Feedback Main Course Material 5 Workload Calculation for this Course 6 Course Assessment: Assignments Overview and Grading Scale 7 Description of Assignments, Activities and Deadlines 8 Rubrics: Transparent Criteria for Assessment 11 Policies for Attendance, Later Work, Academic Honesty, Turnitin 12 Course Schedule – Overview Table 13 Detailed Session-by-Session Description of Course 14 Course Prerequisites (if any) There are no pre-requisites for the course. However, since economics is mathematically intensive, it is worth reviewing secondary school mathematics for a good mastering of the course. A great source which starts with the basics and is available at the VUB library is Simon, C., & Blume, L. (1994). Mathematics for economists. New York: Norton. Course Description The course illustrates the way in which economists view the world. You will learn about basic tools of micro- and macroeconomic analysis and, by applying them, you will understand the behavior of households, firms and government. Problems include: trade and specialization; the operation of markets; industrial structure and economic welfare; the determination of aggregate output and price level; fiscal and monetary policy and foreign exchange rates. -

The Neoclassical Synthesis

Department of Economics- FEA/USP In Search of Lost Time: The Neoclassical Synthesis MICHEL DE VROEY PEDRO GARCIA DUARTE WORKING PAPER SERIES Nº 2012-07 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS, FEA-USP WORKING PAPER Nº 2012-07 In Search of Lost Time: The Neoclassical Synthesis Michel De Vroey ([email protected]) Pedro Garcia Duarte ([email protected]) Abstract: Present day macroeconomics has been sometimes dubbed as the new neoclassical synthesis, suggesting that it constitutes a reincarnation of the neoclassical synthesis of the 1950s. This has prompted us to examine the contents of the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ neoclassical syntheses. Our main conclusion is that the latter bears little resemblance with the former. Additionally, we make three points: (a) from its origins with Paul Samuelson onward the neoclassical synthesis notion had no fixed content and we bring out four main distinct meanings; (b) its most cogent interpretation, defended e.g. by Solow and Mankiw, is a plea for a pluralistic macroeconomics, wherein short-period market non-clearing models would live side by side with long-period market-clearing models; (c) a distinction should be drawn between first and second generation new Keynesian economists as the former defend the old neoclassical synthesis while the latter, with their DSGE models, adhere to the Lucasian view that macroeconomics should be based on a single baseline model. Keywords: neoclassical synthesis; new neoclassical synthesis; DSGE models; Paul Samuelson; Robert Lucas JEL Codes: B22; B30; E12; E13 1 IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME: THE NEOCLASSICAL SYNTHESIS Michel De Vroey1 and Pedro Garcia Duarte2 Introduction Since its inception, macroeconomics has witnessed an alternation between phases of consensus and dissent.