Universal Geogebra Astrolabe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Earth-Centred Universe

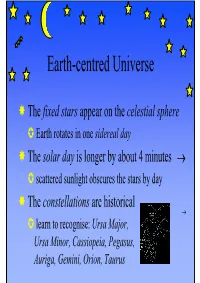

Earth-centred Universe The fixed stars appear on the celestial sphere Earth rotates in one sidereal day The solar day is longer by about 4 minutes → scattered sunlight obscures the stars by day The constellations are historical → learn to recognise: Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Cassiopeia, Pegasus, Auriga, Gemini, Orion, Taurus Sun’s Motion in the Sky The Sun moves West to East against the background of Stars Stars Stars stars Us Us Us Sun Sun Sun z z z Start 1 sidereal day later 1 solar day later Compared to the stars, the Sun takes on average 3 min 56.5 sec extra to go round once The Sun does not travel quite at a constant speed, making the actual length of a solar day vary throughout the year Pleiades Stars near the Sun Sun Above the atmosphere: stars seen near the Sun by the SOHO probe Shield Sun in Taurus Image: Hyades http://sohowww.nascom.nasa.g ov//data/realtime/javagif/gifs/20 070525_0042_c3.gif Constellations Figures courtesy: K & K From The Beauty of the Heavens by C. F. Blunt (1842) The Celestial Sphere The celestial sphere rotates anti-clockwise looking north → Its fixed points are the north celestial pole and the south celestial pole All the stars on the celestial equator are above the Earth’s equator How high in the sky is the pole star? It is as high as your latitude on the Earth Motion of the Sky (animated ) Courtesy: K & K Pole Star above the Horizon To north celestial pole Zenith The latitude of Northern horizon Aberdeen is the angle at 57º the centre of the Earth A Earth shown in the diagram as 57° 57º Equator Centre The pole star is the same angle above the northern horizon as your latitude. -

1 Science LR 2711

A Scientific Response to the Chester Beatty Library Collection Contents The Roots Of Modern Science A Scientific Response To The Chester Beatty Library Collection 1 Science And Technology 2 1 China 3 Science In Antiquity 4 Golden Age Of Islamic Science 5 Transmission Of Knowledge To Europe 6 A Scientific Response To The Chester Beatty Library Collections For Dublin City Of Science 2012 7 East Asian Collections The Great Encyclopaedia of the Yongle Reign (Yongle Dadian) 8 2 Phenomena of the Sky (Tianyuan yuli xiangyi tushuo) 9 Treatise on Astronomy and Chronology (Tianyuan lili daquan) 10 Illustrated Scrolls of Gold Mining on Sado Island (Sado kinzan zukan) 11 Islamic Collections Islamic Medicine 12 3 Medical Compendium, by al-Razi (Al-tibb al-mansuri) 13 Encyclopaedia of Medicine, by Ibn Sina (Al-qanun fi’l-tibb) 14 Treatise on Surgery, by al-Zahrawi (Al-tasrif li-man ‘ajiza ‘an al-ta’lif) 15 Treatise on Human Anatomy, by Mansur ibn Ilyas (Tashrih al-badan) 16 Barber –Surgeon toolkit from 1860 17 Islamic Astronomy and Mathematics 18 The Everlasting Cycles of Lights, by Muhyi al-Din al-Maghribi (Adwar al-anwar mada al-duhur wa-l-akwar) 19 Commentary on the Tadhkira of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi 20 Astrolabes 21 Islamic Technology 22 Abbasid Caliph, Ma’mum at the Hammam 23 European Collections European Science of the Middle Ages 24 4 European Technology: On Military Matters (De Re Militari) 25 European Technology: Concerning Military Matters (De Re Militari) 26 Mining Technology: On the Nature of Metals (De Re Metallica) 27 Fireworks: The triumphal -

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

Ibrāhīm Ibn Sinān Ibn Thābit Ibn Qurra

From: Thomas Hockey et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, Springer Reference. New York: Springer, 2007, p. 574 Courtesy of http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30400-7_697 Ibrāhīm ibn Sinān ibn Thābit ibn Qurra Glen Van Brummelen Born Baghdad, (Iraq), 908/909 Died Baghdad, (Iraq), 946 Ibrāhīm ibn Sinān was a creative scientist who, despite his short life, made numerous important contributions to both mathematics and astronomy. He was born to an illustrious scientific family. As his name suggests his grandfather was the renowned Thābit ibn Qurra; his father Sinān ibn Thābit was also an important mathematician and physician. Ibn Sinān was productive from an early age; according to his autobiography, he began his research at 15 and had written his first work (on shadow instruments) by 16 or 17. We have his own word that he intended to return to Baghdad to make observations to test his astronomical theories. He did return, but it is unknown whether he made his observations. Ibn Sinān died suffering from a swollen liver. Ibn Sinān's mathematical works contain a number of powerful and novel investigations. These include a treatise on how to draw conic sections, useful for the construction of sundials; an elegant and original proof of the theorem that the area of a parabolic segment is 4/3 the inscribed triangle (Archimedes' work on the parabola was not available to the Arabs); a work on tangent circles; and one of the most important Islamic studies on the meaning and use of the ancient Greek technique of analysis and synthesis. -

The Sundial Cities

The Sundial Cities Joel Van Cranenbroeck, Belgium Keywords: Engineering survey;Implementation of plans;Positioning;Spatial planning;Urban renewal; SUMMARY When observing in our modern cities the sun shade gliding along the large surfaces of buildings and towers, an observer can notice that after all the local time could be deduced from the position of the sun. The highest building in the world - the Burj Dubai - is de facto the largest sundial ever designed. The principles of sundials can be understood most easily from an ancient model of the Sun's motion. Science has established that the Earth rotates on its axis, and revolves in an elliptic orbit about the Sun; however, meticulous astronomical observations and physics experiments were required to establish this. For navigational and sundial purposes, it is an excellent approximation to assume that the Sun revolves around a stationary Earth on the celestial sphere, which rotates every 23 hours and 56 minutes about its celestial axis, the line connecting the celestial poles. Since the celestial axis is aligned with the axis about which the Earth rotates, its angle with the local horizontal equals the local geographical latitude. Unlike the fixed stars, the Sun changes its position on the celestial sphere, being at positive declination in summer, at negative declination in winter, and having exactly zero declination (i.e., being on the celestial equator) at the equinoxes. The path of the Sun on the celestial sphere is known as the ecliptic, which passes through the twelve constellations of the zodiac in the course of a year. This model of the Sun's motion helps to understand the principles of sundials. -

Al-Biruni: a Great Muslim Scientist, Philosopher and Historian (973 – 1050 Ad)

Al-Biruni: A Great Muslim Scientist, Philosopher and Historian (973 – 1050 Ad) Riaz Ahmad Abu Raihan Muhammad bin Ahmad, Al-Biruni was born in the suburb of Kath, capital of Khwarizmi (the region of the Amu Darya delta) Kingdom, in the territory of modern Khiva, on 4 September 973 AD.1 He learnt astronomy and mathematics from his teacher Abu Nasr Mansur, a member of the family then ruling at Kath. Al-Biruni made several observations with a meridian ring at Kath in his youth. In 995 Jurjani ruler attacked Kath and drove Al-Biruni into exile in Ray in Iran where he remained for some time and exchanged his observations with Al- Khujandi, famous astronomer which he later discussed in his work Tahdid. In 997 Al-Biruni returned to Kath, where he observed a lunar eclipse that Abu al-Wafa observed in Baghdad, on the basis of which he observed time difference between Kath and Baghdad. In the next few years he visited the Samanid court at Bukhara and Ispahan of Gilan and collected a lot of information for his research work. In 1004 he was back with Jurjania ruler and served as a chief diplomat and a spokesman of the court of Khwarism. But in Spring and Summer of 1017 when Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna conquered Khiva he brought Al-Biruni, along with a host of other scholars and philosophers, to Ghazna. Al-Biruni was then sent to the region near Kabul where he established his observatory.2 Later he was deputed to the study of religion and people of Kabul, Peshawar, and Punjab, Sindh, Baluchistan and other areas of Pakistan and India under the protection of an army regiment. -

The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance

Academia Europaea 19th Annual Conference in cooperation with: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Ministerio de Cultura (Spain) “The Dialogue of Three Cultures and our European Heritage” (Toledo Crucible of the Culture and the Dawn of the Renaissance) 2 - 5 September 2007, Toledo, Spain Chair, Organizing Committee: Prof. Manuel G. Velarde The Persian-Toledan Astronomical Connection and the European Renaissance M. Heydari-Malayeri Paris Observatory Summary This paper aims at presenting a brief overview of astronomical exchanges between the Eastern and Western parts of the Islamic world from the 8th to 14th century. These cultural interactions were in fact vaster involving Persian, Indian, Greek, and Chinese traditions. I will particularly focus on some interesting relations between the Persian astronomical heritage and the Andalusian (Spanish) achievements in that period. After a brief introduction dealing mainly with a couple of terminological remarks, I will present a glimpse of the historical context in which Muslim science developed. In Section 3, the origins of Muslim astronomy will be briefly examined. Section 4 will be concerned with Khwârizmi, the Persian astronomer/mathematician who wrote the first major astronomical work in the Muslim world. His influence on later Andalusian astronomy will be looked into in Section 5. Andalusian astronomy flourished in the 11th century, as will be studied in Section 6. Among its major achievements were the Toledan Tables and the Alfonsine Tables, which will be presented in Section 7. The Tables had a major position in European astronomy until the advent of Copernicus in the 16th century. Since Ptolemy’s models were not satisfactory, Muslim astronomers tried to improve them, as we will see in Section 8. -

Astro110-01 Lecture 7 the Copernican Revolution

Astro110-01 Lecture 7 The Copernican Revolution or the revolutionaries: Nicolas Copernicus (1473-1543) Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) Isaac Newton (1642-1727) who toppled Aristotle’s cosmos 2/2/09 Astro 110-01 Lecture 7 1 Recall: The Greek Geocentric Model of the heavenly spheres (around 400 BC) • Earth is a sphere that rests in the center • The Moon, Sun, and the planets each have their own spheres • The outermost sphere holds the stars • Most famous players: Aristotle and Plato 2/2/09 Aristotle Plato Astro 110-01 Lecture 7 2 But this made it difficult to explain the apparent retrograde motion of planets… Over a period of 10 weeks, Mars appears to stop, back up, then go forward again. Mars Retrograde Motion 2/2/09 Astro 110-01 Lecture 7 3 A way around the problem • Plato had decreed that in the heavens only circular motion was possible. • So, astronomers concocted the scheme of having the planets move in circles, called epicycles, that were themselves centered on other circles, called deferents • If an observation of a planet did not quite fit the existing system of deferents and epicycles, another epicycle could be added to improve the accuracy • This ancient system of astronomy was codified by the Alexandrian Greek astronomer Ptolemy (A.D. 100–170), in a book translated into Arabic and called Almagest. • Almagest remained the principal textbook of astronomy for 1400 years until Copernicus 2/2/09 Astro 110-01 Lecture 7 4 So how does the Ptolemaic model explain retrograde motion? Planets really do go backward in this model. -

Bīrūnī's Telescopic-Shape Instrument for Observing the Lunar

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert Bīrūnī’s Telescopic-Shape Instrument for Observing the Lunar Crescent S. Mohammad Mozaffari and Georg Zotti Abstract:This paper deals with an optical aid named barbakh that Abū al-Ray¬ān al- Bīrūnī (973–1048 AD) proposes for facilitating the observation of the lunar crescent in his al-Qānūn al-Mas‘ūdī VIII.14. The device consists of a long tube mounted on a shaft erected at the centre of the Indian circle, and can rotate around itself and also move in the vertical plane. The main function of this sighting tube is to provide an observer with a darkened environment in order to strengthen his eyesight and give him more focus for finding the narrow crescent near the western horizon about the beginning of a lunar month. We first briefly review the history of altitude-azimuthal observational instruments, and then present a translation of Bīrūnī’s account, visualize the instrument in question by a 3D virtual reconstruction, and comment upon its structure and applicability. Keywords: Astronomical Instrumentation, Medieval Islamic Astronomy, Bīrūnī, Al- Qānūn al-Mas‘ūdī, Barbakh, Indian Circle Introduction: Altitude-Azimuthal Instruments in Islamic Medieval Astronomy. Altitude-azimuthal instruments either are used to measure the horizontal coordinates of a celestial object or to make use of these coordinates to sight a heavenly body. They Suhayl 14 (2015), pp. 167-188 168 S. Mohammad Mozaffari and Georg Zotti belong to the “empirical” type of astronomical instruments.1 None of the classical instruments mentioned in Ptolemy’s Almagest have the simultaneous measurement of both altitude and azimuth of a heavenly object as their main function.2 One of the earliest examples of altitude-azimuthal instruments is described by Abū al-Ray¬ān al- Bīrūnī for the observation of the lunar crescent near the western horizon (the horizontal coordinates are deployed in it to sight the lunar crescent). -

Spherical Trigonometry in the Astronomy of the Medieval Ke Rala School

SPHERICAL TRIGONOMETRY IN THE ASTRONOMY OF THE MEDIEVAL KE RALA SCHOOL KIM PLOFKER Brown University Although the methods of plane trigonometry became the cornerstone of classical Indian math ematical astronomy, the corresponding techniques for exact solution of triangles on the sphere's surface seem never to have been independently developed within this tradition. Numerous rules nevertheless appear in Sanskrit texts for finding the great-circle arcs representing various astro nomical quantities; these were presumably derived not by spherics per se but from plane triangles inside the sphere or from analemmatic projections, and were supplemented by approximate formu las assuming small spherical triangles to be plane. The activity of the school of Madhava (originating in the late fourteenth century in Kerala in South India) in devising, elaborating, and arranging such rules, as well as in refining formulas or interpretations of them that depend upon approximations, has received a good deal of notice. (See, e.g., R.C. Gupta, "Solution of the Astronomical Triangle as Found in the Tantra-Samgraha (A.D. 1500)", Indian Journal of History of Science, vol.9,no.l,1974, 86-99; "Madhava's Rule for Finding Angle between the Ecliptic and the Horizon and Aryabhata's Knowledge of It." in History of Oriental Astronomy, G.Swarup et al., eds., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985, pp. 197-202.) This paper presents another such rule from the Tantrasangraha (TS; ed. K.V.Sarma, Hoshiarpur: VVBIS&IS, 1977) of Madhava's student's son's student, Nllkantha's Somayajin, and examines it in comparison with a similar rule from Islamic spherical astronomy. -

1 the Equatorial Coordinate System

General Astronomy (29:61) Fall 2013 Lecture 3 Notes , August 30, 2013 1 The Equatorial Coordinate System We can define a coordinate system fixed with respect to the stars. Just like we can specify the latitude and longitude of a place on Earth, we can specify the coordinates of a star relative to a coordinate system fixed with respect to the stars. Look at Figure 1.5 of the textbook for a definition of this coordinate system. The Equatorial Coordinate System is similar in concept to longitude and latitude. • Right Ascension ! longitude. The symbol for Right Ascension is α. The units of Right Ascension are hours, minutes, and seconds, just like time • Declination ! latitude. The symbol for Declination is δ. Declination = 0◦ cor- responds to the Celestial Equator, δ = 90◦ corresponds to the North Celestial Pole. Let's look at the Equatorial Coordinates of some objects you should have seen last night. • Arcturus: RA= 14h16m, Dec= +19◦110 (see Appendix A) • Vega: RA= 18h37m, Dec= +38◦470 (see Appendix A) • Venus: RA= 13h02m, Dec= −6◦370 • Saturn: RA= 14h21m, Dec= −11◦410 −! Hand out SC1 charts. Find these objects on them. Now find the constellation of Orion, and read off the Right Ascension and Decli- nation of the middle star in the belt. Next week in lab, you will have the chance to use the computer program Stellar- ium to display the sky and find coordinates of objects (stars, planets). 1.1 Further Remarks on the Equatorial Coordinate System The Equatorial Coordinate System is fundamentally established by the rotation axis of the Earth. -

The Oldest Translation of the Almagest Made for Al-Maʾmūn by Al-Ḥasan Ibn Quraysh: a Text Fragment in Ibn Al-Ṣalāḥ’S Critique on Al-Fārābī’S Commentary

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 The Oldest Translation of the Almagest Made for al-Maʾmūn by al-Ḥasan ibn Quraysh: A Text Fragment in Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ’s Critique on al-Fārābī’s Commentary Thomann, Johannes DOI: https://doi.org/10.1484/M.PALS-EB.5.120176 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-190243 Book Section Accepted Version Originally published at: Thomann, Johannes (2020). The Oldest Translation of the Almagest Made for al-Maʾmūn by al-Ḥasan ibn Quraysh: A Text Fragment in Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ’s Critique on al-Fārābī’s Commentary. In: Juste, David; van Dalen, Benno; Hasse, Dag; Burnett, Charles. Ptolemy’s Science of the Stars in the Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 117-138. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1484/M.PALS-EB.5.120176 The Oldest Translation of the Almagest Made for al-Maʾmūn by al-Ḥasan ibn Quraysh: A Text Fragment in Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ’s Critique on al-Fārābī’s Commentary Johannes Thomann University of Zurich Institute of Asian and Oriental Research [email protected] 1. Life and times of Ibn al-Ṣalāḥ (d. 1154 ce) The first half of the twelfth century was a pivotal time in Western Europe. In that period translation activities from Arabic into Latin became a common enterprise on a large scale in recently conquered territories, of which the centres were Toledo, Palermo and Antioch. This is a well known part of what was called the Renaissance of the Twelfth Century.1 Less known is the situation in the Islamic World during the same period.