Flock Erin K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bush Pdf Free Download

BUSH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jean Edward Smith | 832 pages | 08 Sep 2016 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781476741192 | English | New York, United States Bush | Definition of Bush by Merriam-Webster Keep scrolling for more More Definitions for bush bush. Please tell us where you read or heard it including the quote, if possible. Test Your Knowledge - and learn some interesting things along the way. Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free! Whereas 'coronary' is no so much Put It in the 'Frunk' You can never have too much storage. What Does 'Eighty-Six' Mean? We're intent on clearing it up 'Nip it in the butt' or 'Nip it in the bud'? We're gonna stop you right there Literally How to use a word that literally drives some pe Is Singular 'They' a Better Choice? Name that government! Or something like that. Can you spell these 10 commonly misspelled words? Do you know the person or title these quotes desc Login or Register. Save Word. Bush biographical name 1. Bush biographical name 2. Bush biographical name 3. First Known Use of bush Noun 1 14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 1a Verb 15th century, in the meaning defined at transitive sense Adjective 1 , in the meaning defined at sense 1 Noun 2 , in the meaning defined above Adjective 2 , in the meaning defined above. Keep scrolling for more. The episode included an interview with program host, Nic Harcourt. They toured with Nickelback on their Here and Now Tour. On 26 March , it was reported that Bush had begun recording their sixth studio album with producer Nick Raskulinecz. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

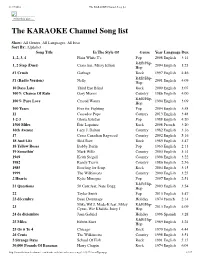

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

SCOREBOARD TUESDAY Ings 1-1, Laimbeer 1-2, Blanks 01)

20—MANCHESTER HERALD, Monday. Feb. 18, 1991 SCOREBOARD TUESDAY ings 1-1, Laimbeer 1-2, Blanks 01). New York 29 (Matteau), 14:39 (sh). 8, SL Louis, Hull 63 3-6 (Tucker 2-2 Vandeweghe 1-3, Jackson Other Saturday scores Women’s Top 25 (Courtnall), 16:02. 9. Calgary, Fenton 11 (Otto), Basketball 0-1). Fouled out—None. Rebounds—Detroit 43 EAST Record Pts 18:03. Penalties—Macoun, Cal (interference), (Rodman 8), Now Ybrk 48 (Oakley 15). As 1. Virginia (60) Hockey LOCAL NEWS INSIDE American U. 82, James Madison 70 24-1 1,618 2:41; Stevens, StL (Interference), 5:33; sists—Detroit 20 (Johnson 6). New York 34 Boston U. 67. Now Hampshire 64. OT 2. Penn SL (1) 23-1 1,533 Makarov, Cal (cross-checking), 13:48; Lowry, NBA standings (Jackson 11). Total fouls— Detroit 20. New Ybrk Brown 66, Penn 60 3. Georgia (4) 22-2 1,509 StL (higfvsticking), 16:27; Musll, Cal (Ngh-stick- 20. TechNcals—Hastings. A— 19,081. Canisius 93, Loyola, Md. 62 4. Tennessee 21- 4 1,416 NHL standings Ing), 16:27; P.Cavalllnl, StL (Interference), EASTERN CONFERENCE 5. Auburn 22- 3 1,381 18:31. ■ Bolton forms new commission. Cornell 95, Harvard 92 WALES CONFERENCE Atlantic Olvltion Racers 113, Kings 110 6. Purdue 21-2 1,263 Third Period—10, Calgary, Fleury 30 (Gil Dartmouth 67, Columbia 61 Patrick Division W L Pet. GB SACRAMENTO (110) DeFYiul 73, Niagara 58 7. N.C, State 21-4 1,183 mour, Nattress), 6:49. 11, St. Louis, W L TPs OF GA Boston 39 1 2 ,765 8. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/27001 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-05 and may be subject to change. DREAMS AND TRANSITIONS THE ROYAL ROAD TO SURINAMESE AND AUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS SOCIETY Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Sociale Wetenschappen PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. C.W.P.M. Blom, volgens besluit van het College van Decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 24 oktober 2005 des ochtends om 10.30 uur precies door Elizabeth Pieternella Mohkamsing-den Boer geboren op 8 januari 1961 te Dordrecht Promotor: prof. dr. A.P. Borsboom Co-promotor: dr. E.M. Venbrux Manuscriptcommissie: mw. prof. dr. W.H.M. Jansen (voorzitter) prof. dr. A.J.M. van den Hoogen mw. dr. T.H. Zock (RUG) Dit onderzoek is gefinancierd door de Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek in de Tropen (WOTRO). This study was funded by the Netherlands Foundation for the Advancement of Tropical Research (WOTRO). Dreams and Transitions: The royal road to Surinamese and Australian Indigenous Society. Thesis Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen - With ref. - With tables. - With summary in Dutch. Cover photograph by Hijn Bijnen © Elizabeth Mohkamsing-den Boer, 2005 ISBN 90-9010315-4 No part of this thesis may be reproduced in any form, by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any informations storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the author. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Connor Oswald

RUMBLE FISH QUARTERLY WINTER 2018 fluence in sync with the neighborhood paper, the story whips along with expert pacing. Upon finishing “The Monitor,” one is left with questions of public shaming, journalistic EDITOR’S NOTE integrity, parental conduct, and community responsibility that linger into the remainder of his or her day, week, and month. While we are beyond excited to share with you these four works, we would be mistaken to give the impression that they are the only thing here that makes us want to squeal. Artwork and photography by Dick Evans and Brian Michael Barbeito make When we started Rumble Fish Quarterly a year ago, things were different. For the ensuing pages a joy to look at. Award-winning poet Rich Murphy offers up “Work one, we didn’t publish unsolicited submissions, and it wasn’t for lack of trying. As it Quirk,” a poem that reads, and we mean this in the most complimentary terms possible, turns out, writers don’t want to submit to a literary magazine whose “Archives” section like a flesh-eating virus. Previous reader-favorite Gerard Sarnat returns with a scriptural consists of the words “Coming Soon!” So we made a list of our most talented friends firecracker of a poem in “Genesis.” Robert Tremmel’s “Dessert Course” bestows upon and asked them nicely if they would entrust their work to our fledgling endeavor. To our the reader one of the more memorable images in Rumble Fish Quarterly’s short history, enormous relief, enough of them obliged to get us started on what we figured would be a and Leigh Holland conquers the far reaches of the page like a white space explorer in her long and winding path to a steady stream of quality submissions. -

A Game of Thrones

A Game Of Thrones Book One of A Song of Ice and Fire By George R. R. Martin PROLOGUE "We should start back," Gared urged as the woods began to grow dark around them. "The wildlings are dead." "Do the dead frighten you?" Ser Waymar Royce asked with just the hint of a smile. Gared did not rise to the bait. He was an old man, past fifty, and he had seen the lordlings come and go. "Dead is dead," he said. "We have no business with the dead." "Are they dead?" Royce asked softly. "What proof have we?" "Will saw them," Gared said. "If he says they are dead, that's proof enough for me." Will had known they would drag him into the quarrel sooner or later. He wished it had been later rather than sooner. "My mother told me that dead men sing no songs," he put in. "My wet nurse said the same thing, Will," Royce replied. "Never believe anything you hear at a woman's tit. There are things to be learned even from the dead." His voice echoed, too loud in the twilit forest. Page 1 "We have a long ride before us," Gared pointed out. "Eight days, maybe nine. And night is falling." Ser Waymar Royce glanced at the sky with disinterest. "It does that every day about this time. Are you unmanned by the dark, Gared?" Will could see the tightness around Gared's mouth, the barely sup pressed anger in his eyes under the thick black hood of his cloak. Gared had spent forty years in the Night's Watch, man and boy, and he was not accustomed to being made light of. -

The Recreations of Christopher North

LIBRARY foiversity of California* IRVINE THE RECREATIONS CHRISTOPHER NORTH. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY n AM. ANTYNE AND HUfiHF.S, PAUL'S WORK, OANONT.ATE. V 5 o o THE RECREATIONS OF CHRISTOPHER NORTH. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. III. WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS, EDINBURGH AND LONDON. M.DCCC.XLII. r/- '- 3 CONTENTS. Ta-'e I. CHRISTOPHER IN HIS AVIAKY FIRST CANTICLE ..... 1 SECOND CANTICLE . 42 THIRD CANTICLE . .77 FOURTH CANTICLE ...... 100 II. DR KITCHINER FIRST COURSE . 123 SECOND COURSE . 143 THIRD COURSE . .153 FOURTH COURSE . H'9 III. SOLILOQUY ON THE SEASONS FIRST RHAPSODY . .186 SECOND RHAPSODY ..... 209 IV. A FEW "WORDS ON THOMSON . 2r9 V. THE SNOWBALL BICKER OF PEDMOUNT . 259 VI. CHRISTMAS DREAMS . .275 VII. OUR WINTER QUARTERS . 303 VIII. STROLL TO GRASSMERE FIRST SAUNTER ..... 33(3 SECOND SAUNTER ...... 377 IX. L'ENVOY US 3 CHKISTOPHEK NORTH. CHRISTOPHER IN HIS AVIARY. FIRST CANTICLE. THE present Age, which, after all, is a very pretty and pleasant one, is feelingly alive and widely awake to the manifold delights and advantages with which the study of Natural History swarms, and especially that branch of it which unfolds the character and habits, physical, moral, and intellectual, of those most interest- ing and admirable creatures Birds. It is familiar not of only with the shape and colour beak, bill, claw, talon, and plume, but with the purposes for which they are designed, and with the instincts which guide their use in the beautiful economy of all-gracious Nature. We remember the time when the very word Ornithology VOL. III. A 2 RECREATIONS OF CHRISTOPHER NORTH. -

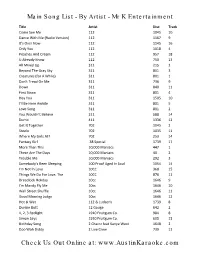

Main Song List - by Artist - Mr K Entertainment

Main Song List - By Artist - Mr K Entertainment Title Artist Disc Track Come See Me 112 1045 10 Dance With Me (Radio Version) 112 1167 9 It's Over Now 112 1145 16 Only You 112 1018 4 Peaches And Cream 112 957 18 U Already Know 112 750 13 All Mixed Up 311 215 2 Beyond The Gray Sky 311 801 3 Creatures (for A While) 311 801 1 Don't Tread On Me 311 736 9 Down 311 840 11 First Straw 311 801 4 Hey You 311 1505 10 I'll Be Here Awhile 311 801 5 Love Song 311 801 2 You Wouldn't Believe 311 588 14 Dumb 411 1336 12 Get It Together 702 1045 2 Steelo 702 1035 11 Where My Girls At? 702 253 14 Fantasy Girl .38 Special 1739 17 More Than This 10,000 Maniacs 447 1 These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs 40 2 Trouble Me 10,000 Maniacs 292 3 Somebody's Been Sleeping 100 Proof Aged In Soul 1054 14 I'm Not In Love 10CC 368 15 Things We Do For Love, The 10CC 876 11 Dreadlock Holiday 10cc 1646 9 I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc 1646 10 Wall Street Shuffle 10cc 1646 11 Good Morning Judge 10cc 1646 12 Hot & Wet 112 & Ludacris 1739 8 Dunkie Butt 12 Gauge 642 2 1, 2, 3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. 984 8 Simon Says 1910 Fruitgum Co. 605 15 Birthday Song 2 Chainz feat Kanye West 1648 2 Doo Wah Diddy 2 Live Crew 739 11 Check Us Out Online at: www.AustinKaraoke.com Main Song List - By Artist - Mr K Entertainment Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 1115 14 We Want Some P**** 2 Live Crew 739 8 California Love 2 Pac 580 8 Changes 2 Pac 724 12 How Do You Want It 2 Pac 132 2 Thugz Mansion 2 Pac 869 14 Until The End Of Time 2 Pac 1163 2 One Day At A Time 2 Pac & Eminem 624 4 Short Dick Man 20 Fingers 425 -

Songs by Artist

Songs By Artist Artist Song Title Disc # Artist Song Title Disc # (children's Songs) I've Been Working On The 04786 (christmas) Pointer Santa Claus Is Coming To 08087 Railroad Sisters, The Town London Bridge Is Falling 05793 (christmas) Presley, Blue Christmas 01032 Down Elvis Mary Had A Little Lamb 06220 (christmas) Reggae Man O Christmas Tree (o 11928 Polly Wolly Doodle 07454 Tannenbaum) (christmas) Sia Everyday Is Christmas 11784 She'll Be Comin' Round The 08344 Mountain (christmas) Strait, Christmas Cookies 11754 Skip To My Lou 08545 George (duet) 50 Cent & Nate 21 Questions 00036 This Old Man 09599 Dogg Three Blind Mice 09631 (duet) Adams, Bryan & When You're Gone 10534 Twinkle Twinkle Little Star 09938 Melanie C. (christian) Swing Low, Sweet Chariot 09228 (duet) Adams, Bryan & All For Love 00228 (christmas) Deck The Halls 02052 Sting & Rod Stewart (duet) Alex & Sierra Scarecrow 08155 Greensleeves 03464 (duet) All Star Tribute What's Goin' On 10428 I Saw Mommy Kissing 04438 Santa Claus (duet) Anka, Paul & Pennies From Heaven 07334 Jingle Bells 05154 Michael Buble (duet) Aqua Barbie Girl 00727 Joy To The World 05169 (duet) Atlantic Starr Always 00342 Little Drummer Boy 05711 I'll Remember You 04667 Rudolph The Red-nosed 07990 Reindeer Secret Lovers 08191 Santa Claus Is Coming To 08088 (duet) Balvin, J. & Safari 08057 Town Pharrell Williams & Bia Sleigh Ride 08564 & Sky Twelve Days Of Christmas, 09934 (duet) Barenaked Ladies If I Had $1,000,000 04597 The (duet) Base, Rob & D.j. It Takes Two 05028 We Wish You A Merry 10324 E-z Rock Christmas (duet) Beyonce & Freedom 03007 (christmas) (duets) Year Snow Miser Song 11989 Kendrick Lamar Without A Santa Claus (duet) Beyonce & Luther Closer I Get To You, The 01633 (christmas) (musical) We Need A Little Christmas 10314 Vandross Mame (duet) Black, Clint & Bad Goodbye, A 00674 (christmas) Andrew Christmas Island 11755 Wynonna Sisters, The (duet) Blige, Mary J. -

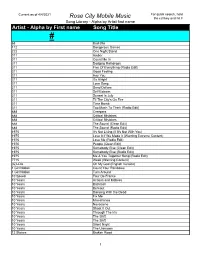

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title # 68 Bad Bite 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 1975 Me & You Together Song (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) (G)I-Dle Oh My God (English Version) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years The Shift 10 Years The Shift 10 Years Silent Night 10 Years The Unknown 12 Stones Broken Road 1 Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975.