Decoding 'Deterrence': a Critique of the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Victim Friendly Responses and Procedures for Prosecuting Rape

Towards Victim Friendly Responses and Procedures for Prosecuting Rape A STUDY OF PRE-TRIAL AND TRIAL STAGES OF RAPE PROSECUTIONS IN DELHI (JAN 2014-MARCH 2015) Partners for Law in Development Conducted with Support of: F-18, First Floor, Jangpura Extension, Department of Justice, New Delhi- 110014 Ministry of Law And Justice T 011- 24316832 / 33 Government of India F 011- 24316833 And E [email protected] United Nations Development Programme TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments iii Executive Summary v Chapter 1: Introduction and Methodology 1 Chapter 2: Overview of Cases and Victims 6 Chapter 3: The Pre-Trial Stage 11 Chapter 4: The Trial Stage 18 Chapter 5: The Need for Support Services 33 Chapter 6: Comparative Law Research 37 Chapter 7: Concluding Observations 46 Annexures Annexure 1: Legislative, Judicial and Executive Guidelines 55 Annexure 2: Templates for Conducting Research 61 Annexure 3: Case Studies (Not for Public Circulation) 65 Annexure 4: Comparative Table of Good Practices from Other Jurisdictions 66 Annexure 5: Letter of Delhi High Court Dated 28.10.2013, Granting Permission For The Study 68 Towards Victim Friendly Responses and Procedures for Prosecuting Rape | i ii | Towards Victim Friendly Responses and Procedures for Prosecuting Rape Acknowledgments This study was conceptualized and executed by Partners for Law in Development, but would not have been possible without the support and engagement of different agencies and individuals, who we express our deep appreciation for. Our gratitude is due to the Delhi High Court for approving this study, enabling us to undertake the trial observation and victim interviews, which were a fundamental part of the research methods for this study. -

Supreme Court of India Miscellaneous Matters to Be Listed on 19-02-2021

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA MISCELLANEOUS MATTERS TO BE LISTED ON 19-02-2021 ADVANCE LIST - AL/1/2021 SNo. Case No. Petitioner / Respondent Petitioner/Respondent Advocate 1 SLP(Crl) No. 6080/2020 JITENDERA TANEJA SANCHIT GARGA II Versus THE STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH AND ANR. SARVESH SINGH BAGHEL, MANISH KUMAR[R-2] APPLICANT-IN-PERSON[IMPL] {Mention Memo} FOR ADMISSION and I.R. and IA No.123635/2020- EXEMPTION FROM FILING C/C OF THE IMPUGNED JUDGMENT and IA No.123634/2020-EXEMPTION FROM FILING O.T. and IA No.129389/2020-INTERVENTION/IMPLEADMENT and IA No.129391/2020-PERMISSION TO APPEAR AND ARGUE IN PERSON, MR. RAM KISHAN, APPLICANT-IN- PERSON HAS FILED APPLICATIONS FOR IMPLEADMENT AS RESPONDENT NO.3 AND PERMISSION TO APPEAR AND ARGUE IN PERSON as per residence by mentioning list on 19.2.2021 IA No. 123635/2020 - EXEMPTION FROM FILING C/C OF THE IMPUGNED JUDGMENT IA No. 123634/2020 - EXEMPTION FROM FILING O.T. IA No. 129389/2020 - INTERVENTION/IMPLEADMENT IA No. 129391/2020 - PERMISSION TO APPEAR AND ARGUE IN PERSON 2 Crl.A. No. 1157/2018 K. BALAJI RAJESH KUMAR II-C Versus THE STATE OF TAMIL NADU REP BY THE INSPECTOR OF M. YOGESH KANNA[R-1] POLICE {Mention Memo} IA No. 67915/2020 - EXEMPTION FROM FILING AFFIDAVIT IA No. 67911/2020 - GRANT OF BAIL 3 Crl.A. No. 191/2020 MADAN LAL KALRA DEVASHISH BHARUKA[P-1] II-C Versus CENTRAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION ARVIND KUMAR SHARMA[R-1] {Mention Memo} only crlmp no. 18696/21 in connected crl.a. -

The Death Penalty

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA LAW COMMISSION OF INDIA Report No.262 The Death Penalty August 2015 U;k;ewfrZ vftr izdk'k 'kgk Justice Ajit Prakash Shah HkwriwoZ eq[; U;k;k/kh'k] fnYyh mPp U;k;ky; Former Chief Justice of Delhi High court v/;{k Chairman Hkkjr dk fof/k vk;ksx Law Commission of India Hkkjr ljdkj Government of India 14ok¡ ry] fgUnqLrku VkbZEl gkÅl] 14th Floor, Hindustan Times House dLrwjck xk¡/kh ekxZ Kasturba Gandhi Marg ubZ fnYyh&110 001 New Delhi – 110 001 D.O. No.6(3)263/2014-LC(LS) 31 August 2015 Dear Mr. Sadananda Gowda ji, The Law Commission of India received a reference from the Supreme Court in Santosh Kumar Satishbhushan Bariyar v. Maharashtra [(2009) 6 SCC 498] and Shankar Kisanrao Khade v. Maharashtra [(2013) 5 SCC 546], to study the issue of the death penalty in India to “allow for an up-to-date and informed discussion and debate on the subject.” This is not the first time that the Commission has been asked to look into the death penalty – the 35th Report (“Capital Punishment”, 1967), notably, is a key report in this regard. That Report recommended the retention of the death penalty in India. The Supreme Court has also, in Bachan Singh v. UOI [AIR 1980 SC 898], upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty, but confined its application to the ‘rarest of rare cases’, to reduce the arbitrariness of the penalty. However, the social, economic and cultural contexts of the country have changed drastically since the 35th report. -

Why Was Dhananjoy Chatterjee Hanged? PEOPLE’S UNIONFORDEMOCRATIC RIGHTS Delhi, September2015 C O N T E N T S

Why was Dhananjoy Chatterjee Hanged? PEOPLE’S UNION FOR DEMOCRATIC RIGHTS Delhi, September 2015 C O N T E N T S PREFACE 1 1. THE FOURTEEN YEARS 2 Box: “Dhananjoy’s petition was a mess—Peter Bleach 3 2. THE RAPIST MUST DIE! VS. RIGHT TO LIVE 4 Box: Ban on documentaries 6 3. THE PROSECUTION’S CASE 7 4. MISSING LINKS 10 5. WAS THAT A FAIR TRIAL? 12 Box: The findings by two professors 15 6. A BIASED JUDGEMENT 17 Box: “Rarest of rare” and the burden of history 18 7. HANG THE POOR 21 8. WHY MUST DHANANJAY CHATTERJEE DIE? 23 P R E F A C E On 14th August 2004, thirty-nine year old Dhananjoy Chatterjee was hanged in Kolkata’s Alipore Correctional Home for the rape and murder of Hetal Parekh in March 1990. The hanging of Dhananjoy was upheld by the courts and by two Presidents as an instance of a “rarest of rare” crime which is punishable with death. Revisiting Dhananjoy’s hanging, the focus of the present report, is a necessary exercise as it sheds some very valuable light on the contemporary debate on the efficacy of death penalty as a justifiable punishment. In 2004, on the eve of the hanging, PUDR did everything possible to prevent it—a last minute mercy petition signed by eminent individuals, an all-night vigil as a mark of protest and, distribution of leaflets for creating a wider public opinion against death penalty (see Box, p 23). Importantly, PUDR’s opposition to Dhananjoy’s execution was not based on his innocence or guilt; instead, the demand for the commutation of his sentence arose out of the opposition to death penalty. -

Andhra Pradesh Andhra Pradesh Andhra Pradesh Andhra

List of Participants of the Workshop on “Role of Puppetry in Education” from March 10 to 25, 2015 at New Delhi. S. No Name & School Address State/UT 1. Shri K. Venkateswarlu Andhra Pradesh 2. Shri Mongam Amrutharao Andhra Pradesh 3. Shri Anakapalli Tatabbayi Andhra Pradesh 4. Smt. Marlapati Kasivisala Andhra Pradesh 5. Shri T. Janakiram Andhra Pradesh 6. Shri P. Satyanarayana Andhra Pradesh 7. Shri Hanumantha Prasad Andhra Pradesh 8. Shri Mamidala Sitaram Andhra Pradesh 9. Shri Shaik Ibrahim Andhra Pradesh 10. Shri Bijit Saikia Assam 11. Shri Pranab Jyoti Nath Assam 12. Shri Sameer Jyoti Borah Assam 13. Shri Nuk Chen Weingken Assam 14. Shri Khamcheng Gogoi Assam 15. Shri Nabajyoti Bhuyan Assam 16. Shri Saurav Patar Assam 17. Shri Nilambar Gupta Chhattisgarh 18. Shri Manoj Kumar Mahana Chhattisgarh 19. Shri Uttam Kumar Mahana Chhattisgarh 20. Shri Rakesh Kumar Yadav Chhattisgarh 21. Shri Pardeep Kumar Haryana 22. Shri Dharampal Haryana 23. Shri Mahesh Kumar Garg Himachal Pradesh 24. Shri Maya Ram Sharma Himachal Pradesh 25. Shri Mailarappa Madar Karnataka 26. Shri Raveendra Bennur Karnataka 27. Smt. Nirmala V. Dodamani Karnataka 28. Shri Vinod Basayya Jangin Karnataka 29. Shri Kannappa. K Karnataka 30. Shri Abdu Shukkoor Areekkadan Kerala 31. Shri Mohamed. AK Kerala 32. Shri K. Mohammed Kerala 33. Shri Abid Pakkada Kerala 34. Shri Noufal. P Kerala 35. Shri Mahroof Khan. MP Kerala 36. Shri Zainudeen. K Kerala 37. Shri Muhammed Twayyib.K Kerala 38. Shri Abdul Lathiph P.S. Kerala 39. Smt. Aruna Mukundral Udawant Maharashtra 40. Smt. Pratibha Shaligram Badgujar Maharashtra 41. Shri Baswanna Maroti Barbade Maharashtra 42. -

Assessing Damage, Urging Action: Report of the Eminent Jurists Panel on Terrorism, Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights

Assessing Action Urging Damage, is report of the Eminent Jurists Panel, based on one of the most comprehensive surveys on counter-terrorism and human rights to date, illustrates the extent to which the responses to the events of 11 September 2001 have changed the legal landscape in countries around the world. Terrorism sows terror, and many States have fallen into a trap set by the terrorists. Ignoring lessons from the past, they have allowed themselves to be rushed into hasty responses, intro- Assessing Damage, ducing an array of measures which undermine cherished values as well as the international legal framework carefully developed since the Second World War. ese measures have Urging Action resulted in human rights violations, including torture, enforced disappearances, secret and arbitrary detentions, and unfair trials. ere has been little accountability for these abuses or justice for their victims. Report of the Eminent Jurists Panel on Terrorism, Counter-terrorism and Human Rights e Panel addresses the consequences of pursuing counter-terrorism within a war paradigm, the increasing importance of intelligence, the use of preventive mechanisms and the role of the criminal justice system in counter-terrorism. Seven years aer 9/11, and sixty years aer Report of the Eminent Jurists Panel the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it is time for the international on Terrorism, Counter-terrorism community to re-group, take remedial action, and reassert core values and principles of inter- and Human Rights national law. ose values and principles were intended to withstand crises, and they provide a robust and eective framework from within which to tackle terrorism. -

List of Employees in Bank of Maharashtra As of 31.07.2020

LIST OF EMPLOYEES IN BANK OF MAHARASHTRA AS OF 31.07.2020 PFNO NAME BRANCH_NAME / ZONE_NAME CADRE GROSS PEN_OPT 12581 HANAMSHET SUNIL KAMALAKANT HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 13840 MAHESH G. MAHABALESHWARKAR HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182402.87 PENSION 14227 NADENDLA RAMBABU HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 14680 DATAR PRAMOD RAMCHANDRA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182116.67 PENSION 16436 KABRA MAHENDRAKUMAR AMARCHAND AURANGABAD ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 168872.35 PENSION 16772 KOLHATKAR VALLABH DAMODAR HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182402.87 PENSION 16860 KHATAWKAR PRASHANT RAMAKANT HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 183517.13 PENSION 18018 DESHPANDE NITYANAND SADASHIV NASIK ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 169370.75 PENSION 18348 CHITRA SHIRISH DATAR DELHI ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 166230.23 PENSION 20620 KAMBLE VIJAYKUMAR NIVRUTTI MUMBAI CITY ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 169331.55 PENSION 20933 N MUNI RAJU HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 172329.83 PENSION 21350 UNNAM RAGHAVENDRA RAO KOLKATA ZONE GENERAL MANAGER 170551.22 PENSION 21519 VIVEK BHASKARRAO GHATE STRESSED ASSET MANAGEMENT BRANCH GENERAL MANAGER 160728.37 PENSION 21571 SANJAY RUDRA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 182204.27 PENSION 22663 VIJAY PRAKASH SRIVASTAVA HEAD OFFICE GENERAL MANAGER 179765.67 PENSION 11631 BAJPAI SUDHIR DEVICHARAN HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13067 KURUP SUBHASH MADHAVAN FORT MUMBAI DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13095 JAT SUBHASHSINGH HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 13573 K. ARVIND SHENOY HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 164483.52 PENSION 13825 WAGHCHAVARE N.A. PUNE CITY ZONE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 155576.88 PENSION 13962 BANSWANI MAHESH CHOITHRAM HEAD OFFICE DEPUTY GENERAL MANAGER 153798.27 PENSION 14359 DAS ALOKKUMAR SUDHIR Retail Assets Branch, New Delhi. -

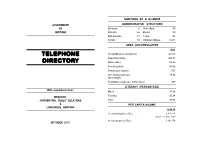

Telephone Directory

HARYANA AT A GLANCE GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE OF Divisions 6 Sub-tehsils 49 HARYANA Districts 22 Blocks 140 Sub-divisions 71 Towns 154 Tehsils 93 Inhabited villages 6,841 AREA AND POPULATION 2011 TELEPHONE Geographical area (sq.kms.) 44,212 Population (lakh) 253.51 DIRECTORY Males (lakh) 134.95 Females (lakh) 118.56 Density (per sq.km.) 573 Decennial growth-rate 19.90 (percentage) Sex Ratio (females per 1000 males) 879 LITERACY (PERCENTAGE) With compliments from : Males 84.06 Females 65.94 DIRECTOR , INFORMATION, PUBLIC RELATIONS Total 75.55 & PER CAPITA INCOME LANGUAGES, HARYANA 2015-16 At constant prices (Rs.) 1,43,211 (at 2011-12 base year) At current prices (Rs.) 1,80,174 (OCTOBER 2017) PERSONAL MEMORANDA Name............................................................................................................................. Designation..................................................................................................... Tel. Off. ...............................................Res. ..................................................... Mobile ................................................ Fax .................................................... Any change as and when occurs e-mail ................................................................................................................ may be intimated to Add. Off. ....................................................................................................... The Deputy Director (Production) Information, Public Relations & Resi. .............................................................................................................. -

In the Supreme Court of India

REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CRIMINAL APPEAL NOS. 165-166 OF 2011 Sunil Damodar Gaikwad … Appellant (s) Versus State of Maharashtra … Respondent (s) J U D G M E N T KURIAN, J.: 1. Death and if not life, death or life, life and if not death, is the swinging progression of the criminal jurisprudence in India as far as capital punishment is concerned. The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898, under Section 367(5) reads: “If the accused is convicted of an offence punishable with death, and the Court sentences him to any punishment other than death, the Court shall in its judgment state the reason why sentence of death was not passed.” (Emphasis supplied) This provision making death the rule was omitted by Act 26 of 1955. 2. There have been extensive discussions and studies on abolition of capital punishment during the first decade of our 1 Page 1 Constitution and the Parliament itself, at one stage had desired to have the views of the Law Commission of India and, accordingly, the Commission submitted a detailed report, Report No. 35 on 19.12.1967. A reference to the introduction to the 35th Report of the Law Commission will be relevant for our discussion. To quote: “A resolution was moved in the Lok Sabha on 21st April, 1962, for the abolition of Capital Punishment. In the course of the debate on the resolution, suggestions were made that a commission or committee should be appointed to go into the question. However, ultimately, a copy of the discussion that had taken place in the House was forwarded to the Law Commission that was, at that time, seized of the question of examining the Code of Criminal Procedure and the Indian Penal Code. -

Jammu Thursday April 12 2018

CyanMagentaYellowBlack K Price 2.00 Pages : 12 K M M Y Y C C JAMMU THURSDAY APRIL 12 2018 VOL. 33 | NO. 100 RNI No. 43798/86 REGD. NO. : JM/JK 118/15 /17 epaper.glimpsesoffuture.com Email: [email protected] WORLD NATIONAL SPORTS FB data leaks: Zuckerberg Atrocities against Shreyasi claims gold to swell says will ensure integrity of minorities, Dalits India's medals tally elections in India increasing: Manmohan Mehbooba meets Pak again violates ceasefire Four civilians, Army trooper killed Rajnath, discusses Kashmir situation in Rajouri, Poonch New Delhi, Apr 11 (PTI) in Kulgam, militants escape 950?@@41>1/1:@?<A>@ 5:B5;81:/15:-99A-:0 -?495> 4512 !5:5?@1> !14.;;.-!A2@5@;0-E91@ ;91 !5:5?@1> &-6:-@4 Srinagar, Apr 11 (KNS): 01:@5-8 4;A?1 @41>1 4-B1 '5:34 -:0 05?/A??10 C5@4 9-:-310 @; 2811 2>;9 @41 459@41?1/A>5@E?5@A-@5;:5: ;A> /5B585-:? -:0 -: ?<;@ 1 05BA8310 @4-@ @41 @41?@-@1-:04;C@;.>5:3 >9E @>;;<1> C1>1 /8-?41? .1@C11: @41 8;/-8? .-/7 :;>9-8/E ;225/5-8? +10:1?0-E7588105:-:1: -:0?1/A>5@E2;>/1?1>A<@:1-> ?-50A>5:3@41 95:A@1 /;A:@1>@4-@>-310.1@C11: @41 1:/;A:@1> ?5@1 -:0 @4-@ 911@5:3 @41 @C; 81-01>? 2;>/1? -:0 9585@-:@? 5: 418<10@419585@-:@?1?/-<1 05?/A??10 @41 5:5@5-@5B1? Jammu, Apr 11 (PTI) :-@125>5:3;2?9-88->9?-A 4A0C-:5 ->1- ;2 ';A@4 E1C5@:1??1? @;80 "' @-71:.E@411:@>1?>1<>1 @;9-@5/?-:09;>@->?-8;:3 -?495>I? A83-9 05?@>5/@ ;B1><4;:1@4-@2;>/1?25>10 ?1:@-@5B1 5:1?4C-> $-75?@-:5 @>;;<? @;0-E @41 ;2>;9 4;A>?5: $;85/1?;A>/1?@;80-?495> 85B1-99A:5@5;:<1881@?-:0 '4->9- 5: 4;805:3 @-87? -3-5: B5;8-@10 /1-?125>1 5: ";C?41>-?1/@;>;2&-6;A>5 -

Life and Death in the Times Of

2020 i COMMONWEALTH HUMAN RIGHTS INITIATIVE The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) is an independent, non-governmental, non-profit organisation headquartered in New Delhi, India, with offices in London, United Kingdom, and Accra, Ghana. Since 1987, it has advocated, engaged and mobilised around human rights issues in Commonwealth countries. Its specialisations in the areas of Access to Justice (ATJ) and Access to Information (ATI) are widely known. The ATJ programme has focussed on Police and Prison Reforms, to reduce arbitrariness and ensure transparency while holding duty bearers to accountability. CHRI looks at policy interventions, including legal remedies, building civil society coalitions and engaging with stakeholders. The ATI programme looks at Right to Information (RTI) LIFE AND DEATH IN THE TIME OF RTI and Freedom of Information laws across geographies, provides specialised advice, sheds light on challenging issues and processes for widespread use of transparency laws and develops capacity. We review pressures on media and CASE STUDIES FROM MAHARASHTRA media rights while a focus on Small States seeks to bring civil society voices to bear on the UN Human Rights Council and the Commonwealth Secretariat. A new area of work is SDG 8.7 whose advocacy, research and mobilisation across geographies is built on tackling contemporary forms of slavery. CHRI has special consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council and is accredited to the Commonwealth Secretariat. Recognised for its expertise by governments, oversight bodies and civil society, CHRI is registered as a society in India, a limited charity in London and an NGO in Ghana. Although the Commonwealth, an association of 54 nations, provided member countries the basis of shared an investigative report by common laws, there was little specific focus on human rights issues in member countries. -

Everyone Blames Me” Barriers to Justice and Support Services for Sexual Assault Survivors in India WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS “Everyone Blames Me” Barriers to Justice and Support Services for Sexual Assault Survivors in India WATCH “Everyone Blames Me” Barriers to Justice and Support Services for Sexual Assault Survivors in India Copyright © 2017 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-35409 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org NOVEMBER 2017 ISBN: 978-1-6231-35409 “Everyone Blames Me” Barriers to Justice and Support Services for Sexual Assault Survivors in India Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Poor Police Response .............................................................................................................. 2 Failure to Provide Access to Adequate Health Services