Towards Anarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frf-Th-Gt Quid, 1/41Rif Rrnagni

Tra•iP17 14th-Tfrokrffo4 otcr6o .564/R9oto-91 /2008-10 1i•631-19 triR2 41-&19-€1 te. Frfth--gt quid, 1/41rif rrnagni zwilk4ftri titebit ZRT IMIRM 3171TariuT tzn LIR itt tgu M- (.1c-cpi 34 zi aif41k4R) Wald), IETqW, 25 t5T441,- 2009- th-T9W 6, 1930 'Ti tP-qt-1, .3-c1' srevr tHcm( Thvrtit artirTr-i tit-WE 379/79-M-1-09-1(31-2008 \th, 25 45T4t, 2009 aifirip-gr real "R1T T51 vif4w9" Z 34-1-14-4 200 31th9 Iuq4ftfTF&C-6 \icth Irk71 .C1 vc4 ft`46e4E11-6•6 (347N47) ffitttrT, 2008 tri ita 24 ER611, 2009 3ITIra 145I-141 aft•q 6-6• .1*41. 3altRITI TSIT 6 39 2009 *Wig 4 3r4-fittimir 413T9P4 niaTRifki TR1" p--611%-a faun vircir ‘scc-H Ycl tfic-14 (Tit-T9) 3litThWf, 2008 Omit ti &TRAIN \1ts441 6 39 2009) [ \3c1-/4 i•1 3Thi fdcari Huse{Ti tITRU pin cri 34 •?iver G1qRcjim 3aAttri 1973 5T 311073471•1t19. *.itic • 1-TEM hIUkIt4 \i1\90 nti f3/41WZgrr Si714 turn \snot 5 :- 1-z15 3*ftli \iccrt vuzi Rxcgavicrtzt WAIN S, 2008 Th5T 7P1 'wrrrr UiTZ wa7I 31TITE11uf , 25 tffcl1. 2009 2-3TKIR sthl ti7g4ffictIvIdZI3TRAtrii, 1973 ftgiO 1k.9 30P11111 43kgi 3611.111P1 *TU9 29 t egNI 5 4,- 79 1974 &RI • =mead 34? () (1) VT MET Thm4f11hn41u ififiTh-TF fb) 1/4410; Tr NW-eta 311i7l1tf 311:4P4Z111 (G) 3111/RT (3) 4* fkm-iF RIR* -31TRITT I RR= 1.0 319 1973 itt urt 5 9,1 tgt-grt URI 37 ±1 3-93IIflPTqThcl UM 37 k 311‘1Tirf (1) W19 *3 P117, GLP-rm ulig)11. -

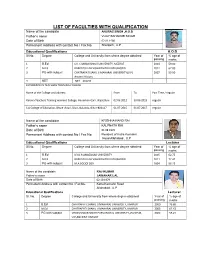

List of Faculties with Qualification

LIST OF FACULTIES WITH QUALIFICATION Name of the candidate ANURAG SINGH ,H.O.D Father’s name VIJAY BAHADUR SINGH Date of Birth 02.01.1980 Permanent Address with contact No / Fax No. Shergarh , U.P Educational Qualifications H.O.D Sl.No. Degree College and University from where degree obtained Year of % age of passing marks 1 B.Ed CH. CHARAN SINGH UNIVERSITY, MEERUT 2004 59.00 2 M.Ed BARKATULLAH VISHWAVIDYALAYA,BHOPAL 2012 67.00 3 PG with subject CHATRAPATI SAHU JI MAHARAJ UNIVERSITY(U.P) 2007 59.00 Ancient History 4 NET NET – 2012 D EXPERIENCE IN TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE Name of the College and address From To Part Time / regular Karona Teachers Training womens College, Hanuman Garh, Rajasthan 02.06.2012 30.06.2015 regular S.A College of Education, Bhuie ,Road, Silao, Nalanda, Bihar‐803117 01.07.2015 01.07.2017 regular Name of the candidate KRISHNA NAND RAI Father’s name KALPNATH RAI Date of Birth 01.08.1976 Permanent Address with contact No / Fax No. Resident of Katra Kachahri Road Allahabad , U.P Educational Qualifications Lecturer Sl.No. Degree College and University from where degree obtained Year of % age of passing marks 1 B.Ed DR.B.R AMBEDKAR UNIVERSITY 2005 62.75 2 M.Ed BARKATULLAH VISHWAVIDYALAYA,BHOPAL 2011 72.42 3 PG with subject M.A SOCIOLOGY 2004 56.23 Name of the candidate RAJ KUMAR Father’s name JAWAHAR LAL Date of Birth 02.10.1979 Permanent Address with contact No / Fax No. Katra Kachahri Road Allahabad , U.P Educational Qualifications Lecturer Sl. -

LLB(Hons) V Sem 2017 23‐Mar‐17

LLB(Hons) V Sem 2017 23‐Mar‐17 Unit Roll No Enrol No Name Father;s Name Mother's Name M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 M6 M7 Total Result AU 43002 14AU/1190 ABHISHEK KUMAR TRIPATHI DHARMENDRA KUMAR TRIP LALITA TRIPATHI AA AA AA AA AA AA AA Abs Absent AU 43003 14AU/959 ABHISHEK SHUKLA CHANDRA MAULI SHUKLA USHA DEVI 56 56 55 55 55 61 60 398 Passed AU 43004 U0721375 ABHISHEK SINGH JAGDAMBA SHARAN SINGH USHA SINGH 52 55 57 53 55 57 56 385 Passed AU 43005 U0722128 ABHISHEK SRIVASTAVA DINESH KUMAR SRIVASTAVA POONAM SRIVASTA 53 63 43 56 54 64 58 391 Passed AU 43006 G1130009 ADARSH SINGH RAKESH SINGH BHADAURIYA MEERA SINGH 59 62 57 57 60 62 58 415 Passed AU 43007 U9520597 AHSAN AHMED KHAN NASIR AHMED KHAN SHAMIUN NISHA 55 55 AA 54 56 58 57 335 Elig.for SE AU 43008 14AU/2082 AISHVARYA VIKRAM ANIL KUMAR SINGH USHA SINGH 60 61 58 57 60 58 63 417 Passed AU 43010 14AU/814 AJAY KUMAR PAL SANCHU PAL AMIRATA DEVI 55 59 48 51 55 57 60 385 Passed AU 43012 U0920465 AKASH DEEP SINGH VIJAY PRATAP SINGH CHANDRAKALA SING 61 64 60 54 61 60 58 418 Passed AU 43013 U1010016 AKASH TIWARI JUGRAJ TIWARI SUNITA TIWARI 66 56 64 62 69 62 56 435 Passed AU 43015 U0521780 AKHILESH KUMAR SAROJ KESHAV SAROJ KAMALAVATI DEVI 56 61 62 54 55 55 52 395 Passed AU 43017 11AU1146 ALOK JAISWAL RADHEY SHYAM JAISWAL KALAVATI JAISWAL 55 45 54 53 56 58 53 374 Passed AU 43018 U0820313 ALOK KUMAR SINGH VIR BAHADUR SINGH NEELA SINGH AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAbsAbsent AU 43019 14AU/2090 ALOK KUMAR YADAV NAND LAL YADAV INDRA KALI YADAV 54 43 52 51 56 60 54 370 Passed AU 43020 U0820057 ALTAF HUSAIN BABAR HARUN RASID ASHAMA -

ZINTETRTIT 1I41 Tirpitie 41Ir-1, T.Qu (\Tcp( Sir Atft-Ftzrit)

tic (-1) -1.4.(-71071041o/ [Fab secio/kro1 fo-91/2014-16 en* -if te ief t-d JR47 rd‘ TaVitzi titem IRT TRAM ZINTETRTIT 1i41 tiRPitie 41ir-1, t.qu (\tcp( sir aTft-ftzrIT) c4N-1th, 911,1, 5 3PIRI, 2019 49-4u1 14, 1941 'TM meact %flit iltf x11•94 ?anti 3TIffrir- —i +NA( 1446/79-174-1-19-13-19 eittith, 5 3111WF, 2019 affer-fo7r ittsr 71 ‘371( 5R7 (Pt( F4Re4 "17ff61 TritaTiff" aira 200 04M ti,TeNkti lit4 11M, 2019 (TiiltF) itIzIT, 2019 ThOf ‘Pr-f %ZiT 31T1FT-1 ARTrefr* WI tieciRid tR R94 2 01 79.ret arlRft scav aSr tiin 6 WI 2019 WIA kreltritri(ur z-fr aiftri-AT aRr srQD7 itzif 7r-dr WI \ick-N A-kW •tluzi f1cl114IcW (7V1)V9.) 3TffilkzPi, 2019 Ock-K liaxf 31telk411 titsit 6 2019) [1/431ti1 \icctt ar foirff fluscrr gk1 ErrRff prr] R• Tie-T9 maxr •flotr facirastieltr ST, 1973 Th-T arlid- f*.ifRgyr 3TWIffiZN crimr..41 t giNd 41.k1v4 * -fr-d-Rt 9•Fr -kV 9 aki 'tot! fazur1vici4 tifeltT9) 311W49Ti, 2019 zrg 3Titf471 \it vrnIT .114411. 1 (2) zrg Wa 7 fl'1, 2019 Thl• ;Fr gan. ,4-141$11 WIPE! I85_RPH_Data 4 Vidhaika Folder (Adhiniyam_2019) • 2 AtZT 3TRITS1TRuf fivid, 5 3171Wf, 2019 .sccrl 17t4T 2— \ict-PE arfi1/474 lPlElIcll4 3M447, 1973, Da 344 affilikzur r 3Tifri-ZN Th7T 7171T t, S UM 4 11, 311URT (1—) k — 29 9 1974 grir <9u4 NO 14, t1;w11€11q kil5i CIA awzrr wtr4 zraTri4vr1Nrff vT -314ivfr Re.11 WtilT; arf4ftqft (RR) Cslud NO 4 sic4 *c116.16114 '<lug ivitatileig, $0161•41C <itctifirr 7x44 sic< "mlitfR ,(1,31-i Rig ( m, Tina) alfe4=riT wiucrr ,, 10, 'f19 1973 viia4; tf MT 4 ff (TI) Nud (7) Tr4wq, qi-ifMtict iug 44-r f4-4 3121fq "(sr) kr7 xi Eimer, +416“13 Mrti • Yci Idef, egNiv u1111 ‘3114 41i;" "(5i) t cinuiciet 3TMIFT-4- ,t1w4 IQ11EJML 3117e4-4* vilir ETTRT 50 3-1:17 71tf444 tar tiRT 50 k 3METTVT (1-3") f*i cf v4i WRINK 4-qf t aft, 7e1fq ff7 ftni 31tftff S sitni NRPIIHI4eiT 1IT A u44, ut V101- wRiTr Rt. -

Advocates in District Court, Ballia

Advocates in District Court, Ballia S.No. Name Father's Name Registration No. Address JUTHI TIWARI KE TOLA, ACHLGARH, BALLIA 1 RAM NIWASH TIWARI LATE BRIJNATH TIWARI UP1714/1987 ### U.P. VILL-PANDEYPUR, P.O. TAKHA, DISTT 2 SHIV KRIPA PANDEY NARENDRA NATH PANDEY UP5618/2006 ### BALLIA, UP VILL SAEMPUR, POST ISARI SALEMPUR, AKHILESH KUMAR SINGH LATE BHAGWATI SHARAN SINGH UP1541/1995 ### 3 BALLIA 4 PRASHANT MISHRA RAMA SHANKER MISHRA UP7913/2001 ADHIWAKTA NAGAR BALLIA ### 5 RAMASHANKAR MISHRA LATE BALBHADRA MISHRA UP3145/1995 ADVOCATE COLONY, BALLIA ### 6 ATUL KUMAR SRIVASTAVA DAYA NAND SRIVASTAVA UP3489/1992 YADAV NIVAS KOTWALI HARPUR BALLIA UP### VILL POST SAGARPALI PHEPHNA DISTT RAJIV KUMAR SRIVASTAVA LATE RAJENDRA PRASAD UP2276/2005 ### 7 BALLIA VUILL MAHUWEE POST SHIVPUR GANESH JI PANDEY LATE RAM LAL PANDEY UP3374/2013 ### 8 (DATTIWAR) DISTT BALLIA UP MOHALLA MILKI, POST SIKANDERPUR, SARWAT MOID LATE ABDUL NOID UP616/1986 ### 9 DISTT BALLIA UP VILL- SHUKLA CHHAPRA POST – 10 ARUN KUMAR SHUKLA LATE RAM KRIPAL SHUKLA UP679/1987 ### MAJHAUWAN , BALLIA 11 MANOJ KUMAR SINGH AWADHESH KUMAR SINGH UP4167/1996 VILL – GAYGHAT VIA- REOTI BALLIA ### VILL – KUMHAILA POLICE STATION – 12 VIRENDRA KUMAR SINGH LATE RAJ KISHORE SINGH UP4084/1986 ### SHUKHPURA , BALLIA 13 HARINDRA NATH SINGH LAET SHIV DATT SINGH UP666/1998 VILL – APAIL, APAIL, BALLIA ### 14 SANJEEV KUMAR RAI LATE MADAN GOPAL RAI UP11933/1999 VILL – NARHI , POST – NARHI, BALLIA ### MOHALLA – ANAND NAGAR , NAI BASTI , 15 PREM KUMAR SHUKLA LATE VACHASPATI SHUKLA UP17604/1999 ### BALLIA 16 -

Jats Into Kisans

TIF - Jats into Kisans SATENDRA KUMAR April 2, 2021 Farmers attending the kisan mahapanchayat at Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, 29 January. The tractors carry the flag of the Bharatiya Kisan Union | ChalChitra Abhiyaan The decline of farmer identity from the 1990s brought a generation of upwardly mobile Jats close to the BJP. The waning of urban economic opportunities has reminded youth of the security from ties to the land, spurring the resistance to the farm laws. Following the Bharatiya Janata Party government’s attempt earlier this year to forcibly remove farmers protesting the farm laws on the borders of Delhi, the epicentre of the movement has shifted deep into the Jat- dominated villages of western Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Haryana. The large presence of Muslim farmers in the several kisan mahapanchayats across the region has been read as a sign of a reemergence of a farmers’ identity, an identity that had been torn apart by the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots that pitted the mostly Hindu Jats against Muslims. Neither the Jat claim to Hindutva a few years ago nor the re-emergence of a farmer identity in the present happened overnight. The deepening agrarian crisis and changes in social relations in western UP since the 1990s had accelerated social and spatial mobilities in the region, leading to fissures in the farmer’s polity and the BJP gaining politically. A younger generation of upward mobile Jats, dislocated from agriculture, hardly identified with the kisan identity. Urban workspaces and cultures began shaping their socio-political identities. New forms Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in April 2, 2021 of sociality hitched their aspirations to the politics of the urban upper-middle classes and brought them closer to the politics of the Hindu right. -

Joshi 48 Agrarian Transformation and the Trajectory of Farmers

ERPI 2018 International Conference Authoritarian Populism and the Rural World Conference Paper No.48 Agrarian Transformation and the trajectory of Farmers’ Movements Siddharth K Joshi 17-18 March 2018 International Institute of Social Studies (ISS) in The Hague, Netherlands Organized jointly by: In collaboration with: Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely those of the authors in their private capacity and do not in any way represent the views of organizers and funders of the conference. March, 2018 Check regular updates via ERPI website: www.iss.nl/erpi ERPI 2018 International Conference - Authoritarian Populism and the Rural World Agrarian Transformation and the trajectory of Farmers’ Movements Siddharth K Joshi 1 Introduction The period of 1980s saw the emergence of massive farmers’ movements on the horizon of Indian politics (Brass, 1995). In 1988, Bhartiya Kisan Union (BKU) made a late albeit spectacular entry on to this scene with a sit-in at the Boat Club Delhi where the India Prime Minister was slated to address a rally in a weeks time. Lakhs of farmers, led by their rustic leader Mahendra Singh Tikait, blockaded roads for days with their bullock carts and trolleys. Unable to get the farmers to budge, the PM decided to shift the venue of his rally instead. From those heady days of movement politics in 1988, things were starkly different in Sept 2014, when I made my first (of three) field trips in Sept 2014 to Muzaffarnagar district in western Uttar Pradesh. Muzaffarnagar was where it all began for Bhartiya Kisan Union (BKU) in 1987 when firing on a peaceful demonstration (gherao) which killed two farmers, snowballed into a region-wide movement which saw several demonstrations attended by lakhs of farmers for over 30-40 days on some occasions. -

The Case of Bhartiya Kisan Union

Traditional Institutions and Cultural Practices vis-à-vis Agrarian Mobilisation: The Case of Bhartiya Kisan Union Gaurang R. Sahay Based on a study of the Bhartiya Kisan Union (BKU) and the farmer/ peasant movements in western Uttar Pradesh (UP) during 1987-89, this paper deals with the relationship between traditional socio- cultural institutions and cultural practices on the one hand, and agrarian mobilisation, on the other. It is shown that, during 1987-89, when the BKU organised various successful agitations and move- ments against the state by mobilising the farmers/peasants of western UP on a large scale, its strategies of agrarian mobilisation were rooted in and modelled on the traditional sociocultural system of the local agrarian society. The BKU used the primordial institutions of caste and clan to organise and mobilise the farmers; it used tradi- tional cultural practices or symbols to generate consciousness, senti- ments and enthusiasm; and it used the traditional institution of panchayat for discussions and deliberations, and to address the farmers. The paper also shows that the BKU began declining when it entered electoral politics and started mobilising the farmers on political lines. In this paper, I have tried to delineate the relationship between traditional cultural practices and institutions of caste, clan and panchayat, on the one hand, and agrarian mobilisation, on the other, by making a case study of the Bhartiya Kisan Union (hereafter BKU). The BKU has been, from about 1986, the champion of the farmers or peasants of western Uttar Pradesh (hereafter UP). It is found that, during 1987-89, the BKU organised a number of highly successful movements or agitations against the state by successfully mobilising the farmers and effectively deploy- ing the cultural practices and traditional institutions. -

Peasant Movements in India Then and Now

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review Peasant Movements in India Then and Now Dr. S. Kumar Swami India is an agricultural country. Agricultural peasantry at the centre of the revolution. production has been the means of the live of the Dipankar Gupta argues about the two kinds of Indian people since ages. In ancient and medieval agrarian movements in independence. India, states formed and abolished because of agricultural production. The rich agricultural First, those agrarian movements which production situation attracted many invaders to are done by the poor agriculture labourers and attack on India. Agricultural revenue was the main marginal farmers, and these kinds of movements source of income for the states in India. In ancient are known as peasants movement. Second, those and medieval India, states became powerful due agrarian movements which are done by the owners to the revenue collection. But, during medieval of the land and these are known as farmers period, tax revenue collection was not oppressive. movement. The first type of agrarian movements Therefore, peasants’ movement did not appear are led by political parties and farmers' till medieval period. But, the arrival of European associations such as Kisan Sabha, Communist companies, brought new revenue collecting Party of India (CPI), Communist Party of India- pattern. Their objective was to get more benefits Marxist (CPI- M), Communist Party of India because the foundation of those companies was (Marxist-Leninist) (CPI-ML) etc. The second done for doing business. The British East India type of agrarian movements are led by farmers' Company of England conquered India by groups such as, Bharatiya Kisan Union which is politically as well as economically. -

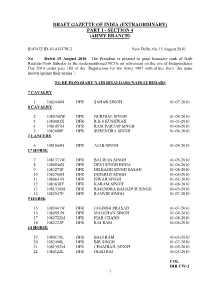

Draft Gazette of India (Extraordinary) Part I - Section 4 (Army Branch)

DRAFT GAZETTE OF INDIA (EXTRAORDINARY) PART I - SECTION 4 (ARMY BRANCH) B/43432/ID-10/AG/CW-2 New Delhi, the 15 August 2010 No Dated 15 August 2010. The President is pleased to grant honorary rank of Naib Risaldar/Naib Subedar to the undermentioned NCOs on retirement on the eve of Independence Day 2010 under para 180 of the Regulations for the Army 1987 with effect from the dates shown against their names :- TO BE HONORARY NAIB RISALDARS/NAIB SUBEDARS 7 CAVALRY 1 1082440N DFR SAHAB SINGH 01-07-2010 8 CAVALRY 2 1080768W DFR GURDIAL SINGH 01-04-2010 3 1080083X DFR R B S KUSHWAH 01-03-2010 4 1081897H DFR RAM PARTAP SINGH 01-06-2010 5 1082698F DFR SURENDRA SINGH 01-08-2010 2 LANCERS 6 1081060H DFR AJAB SINGH 01-04-2010 17 HORSE 7 1081371W DFR BALWAN SINGH 01-05-2010 8 1080946N DFR DEVI SINGH INDIA 01-04-2010 9 1083273P DFR DILBAGH SINGH SASAN 01-08-2010 10 1082760H DFR INDERJIT SINGH 01-06-2010 11 1080641N DFR ISWAR SINGH 01-03-2010 12 1083638Y DFR KARAM SINGH 01-08-2010 13 1081330M DFR RAJENDRA BAHADUR SINGH 01-05-2010 14 1082947P DFR RANVIR SINGH 01-07-2010 9 HORSE 15 1082441W DFR JAGDISH PRASAD 01-07-2010 16 1080591N DFR MALKHAN SINGH 01-04-2010 17 1082722M DFR PIAR CHAND 01-08-2010 18 1082222P DFR RAJ RAM 01-06-2010 14 HORSE 19 1080119L DFR BALI RAM 01-03-2010 20 1082498L DFR BIR SINGH 01-07-2010 21 1081392M DFR CHAMBAIL SINGH 01-05-2010 22 1080122L DFR DESH RAJ 01-03-2010 COL DIR CW-2 1 23 1080423P DFR KULDIP CHAND 01-03-2010 24 1080903Y DFR MOHAN LAL 01-05-2010 25 1082206X DFR RAJWINDER SINGH 01-06-2010 18 CAVALRY 26 1081433L DFR VIRENDRA -

Here. the Police Stopped Them at the Gate

[This article was originally published in serialized form on The Wall Street Journal’s India Real Time from Dec. 3 to Dec. 8, 2012.] Our story begins in 1949, two years after India became an independent nation following centuries of rule by Mughal emperors and then the British. What happened back then in the dead of night in a mosque in a northern Indian town came to define the new nation, and continues to shape the world’s largest democracy today. The legal and political drama that ensued, spanning six decades, has loomed large in the terms of five prime ministers. It has made and broken political careers, exposed the limits of the law in grappling with matters of faith, and led to violence that killed thousands. And, 20 years ago this week, Ayodhya was the scene of one of the worst incidents of inter-religious brutality in India’s history. On a spiritual level, it is a tale of efforts to define the divine in human terms. Ultimately, it poses for every Indian a question that still lingers as the country aspires to a new role as an international economic power: Are we a Hindu nation, or a nation of many equal religions? 1 CHAPTER ONE: Copyright: The British Library Board Details of an 18th century painting of Ayodhya. The Sarayu river winds its way from the Nepalese border across the plains of north India. Not long before its churning gray waters meet the mighty Ganga, it flows past the town of Ayodhya. In 1949, as it is today, Ayodhya was a quiet town of temples, narrow byways, wandering cows and the ancient, mossy walls of ashrams and shrines. -

Daily Vocab-554

DAILY VOCAB DIGESTIVE (25th-FEB-2021) AMID FAULT LINES, A REVIVAL OF THE FARMERS’ IDENTITY Signs of a polarised western U.P. and its agrarian communities unifying are visible in the ongoing farmers’ movement This year in Uttar Pradesh, thousands of farmers gathered on January 29, at the government inter-college ground, Muzaffarnagar, following a call by the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU) president, Naresh Tikait, for a ‘mahapanchayat’ to express solidarity with the protest at the Ghazipur border led by his brother, Rakesh Tikait. Among the key speakers was Ghulam Mohammad Jaula, the most influential Muslim leader of the BKU, and considered to be a close friend of the late Mahendra Singh Tikait. The presence of Mr. Jaula and Muslim farmers at the meet has been read as a sign of a re-emerging Jat- Muslim alliance under the kisan identity after the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots affected the social fabric in rural western U.P. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its regional leadership were behind a local caste dispute growing into a communal issue that polarised villages along religious lines. At the time, it seemed that Jat farmers had suddenly claimed the Hindutva identity. But that did not happen overnight. The farmers’ polity has had deep roots while farmers’ mobilisations have a long history in the western U.P. region. The ongoing agrarian change and crisis generated by neoliberal economic policies have shifted the agrarian economy to non-farm occupations. These new developments caused fissures in the farmer’s polity in the north-western region, giving the BJP a political advantage.